Month: September 2011

The magic of compound interest?

Because thanks to an eccentric New York lawyer in the 1930s, this college [Hartwick] in a corner of the Catskills inherited a thousand-year trust that would not mature until the year 2936: a gift whose accumulated compound interest, the New York Times reported in 1961, “could ultimately shatter the nation’s financial structure.”

The real rate of compound interest may or may not in the long run exceed the rate of economic growth, so the size of the trust could be enormous in the 29th century but still small or mid-sized relative to the size of the economy.

The problem becomes especially acute when existential or catastrophic risk is significant. Long-term savers then earn a higher risk premium and the compounding is more intense. It is possible that the rate of return on these investments — if the world survives — is quite high relative to the rate of economic growth. In effect, existential risk means the long-term savers will rule the world, if there is a world to rule of course.

The article is here — interesting throughout — and for the pointer I thank Umung Varma.

Addendum: Robin Hanson offers comment.

Haiti fact of the day

UN: Official aid disbursed to Haiti in 2010-11 was 43% of pledge. Only 1% went through Haitian government.

The source link is here.

About what am I optimistic and pessimistic?

Rahul asks:

Reading Tyler’s views on the great stagnation, American deficit, American politics, the Euro, Greece, Medicare, Social Security, climate issues etc. I hardly see a sliver of optimism anywhere.

What things is Tyler really optimistic about?

Beware the fallacy of mood affiliation! (Choosing a view to correspond to an overall desired or appropriate mood.) And don’t overrate the importance of the public sector. A few points:

1. I am a utility optimist and a revenue pessimist; better that than the other way around.

2. Many readers of TGS neglect the last section of the book which notes that a) the great stagnation is going to end, and b) we’ve already made the critical breakthrough, namely internet/computers/smart machines, we just haven’t seen most of the gains yet and they may take longer than most people expect. I’ll be writing more on this.

3. I am a pessimist about the euro but not Europe. The continent will do fine once it gets past this mess, albeit with some suffering along the way.

4. I am optimistic about most social issues, such as the increasing felicity of marriage.

5. I am optimistic about how well immigration will go.

6. I am optimistic about human cognition and the Flynn effect.

7. I am optimistic about the future progress of medical care, albeit with some lags.

8. I am increasingly optimistic about the WMD terrorism issue, though I am not sure if I am in absolute terms an optimist on this issue. The terror groups don’t seem very robust or well-organized, and that may be for reasons which are intrinsic to their operations and ideology.

9. I am optimistic about most developing countries and this is a significant issue.

10. I am a pessimist about climate change and biodiversity, though most other environmental issues seem fine or at least manageable and possibly improving.

11. I am a pessimist about how we treat animals.

12. I am an optimist about restaurants in northern Virginia.

Seeing is Hearing: The McGurk Effect

Very cool auditory illusion created by visual dominance.

Hat tip to Carpe Diem.

North Korean photos

Sorry for the bad link from yesterday, find them here. I thank Yana for the pointer.

No reason not to do this

Siemens withdrew more than half-a-billion euros in cash deposits from a large French bank two weeks ago and transferred it to the European Central Bank, in a sign of how companies are seeking havens amid Europe’s sovereign debt crisis.

The story is here.

Assorted links

Markets in everything, old school edition

From 1836 to 1940, the Bellville family of London operated a business of letting people know the time. Ruth Bellville, the most famous member of that family, walked around London with a high grade watch that had been set to within one tenth of a second of the Royal Observatory in Greenwich. For a fee, she’d tell you the current time…Belville continued to ply her trade up to the age of 86, including making the twelve-mile journey on foot to Greenwich.

Here is the post and I thank John Thorne and Peter Metrinko for the pointers.

Is the eurozone crisis a sovereign fiscal crisis?

It is fashionable to say no (Greece aside), citing the low reported deficits before the crisis. Spain even had a budget surplus for a while.

Yet the correct answer is “yes, the eurozone crisis is a sovereign fiscal crisis.”

It is not only a fiscal crisis, by any means, but a sovereign fiscal crisis it is and not just ex post.

Let’s say a government had on paper a balanced budget, but wrote a very large naked put, large relative to gdp. That is not a fiscally sound position, even though it may look OK in the published budget. If the implicit financial position becomes a vulnerable one, that government is then insolvent or nearly insolvent, even though you can point to their ex ante balanced budget.

That situation is analogous to the EU, pre-crisis. The implied naked put was the commitment of governments and banking systems to maintain a one-to-one price between euros in German banks and euros in the banks of the periphery countries. That position has now gone bad.

In bad times, and when accounting gimmicks are rampant, a government’s fiscal policy is best understood as a portfolio of options positions, not in terms of a static balance sheet.

To point to the initial balance sheet is to miss why the whole system didn’t work in the first place.

That said, it remains the case that fiscal austerity on the published balance sheet isn’t a solution. The governments either have to stop writing the naked puts or prove they can make good on them.

Contagion

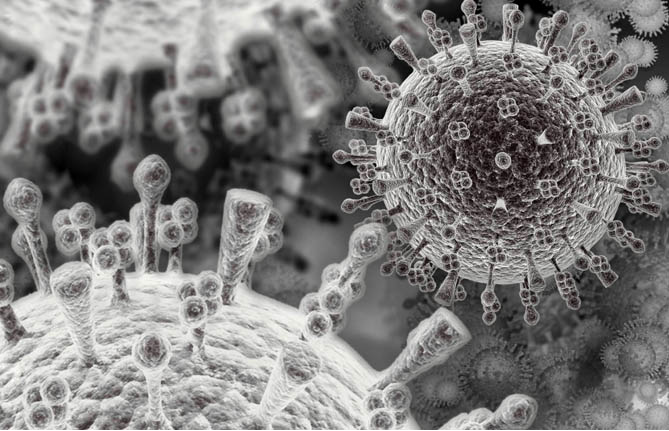

Contagion, the Steven Soderberg film about a lethal virus that goes pandemic, succeeds well as a movie and very well as a warning. The movie is particularly good at explaining the science of contagion: how a virus can spread from hand to cup to lip, from Kowloon to Minneapolis to Calcutta, within a matter of days.

One of the few silver linings from the 9/11 and anthrax attacks is that we have invested some $50 billion in preparing for bio-terrorism. The headline project, Project Bioshield, was supposed to produce vaccines and treatments for anthrax, botulinum toxin, Ebola, and plague but that has not gone well. An unintended consequence of greater fear of bio-terrorism, however, has been a significant improvement in our ability to deal with natural attacks. In Contagion a U.S. general asks Dr. Ellis Cheever (Laurence Fishburne) of the CDC whether they could be looking at a weaponized agent. Cheever responds:

Someone doesn’t has to weaponize the bird flu. The birds are doing that.

That is exactly right. Fortunately, under the umbrella of bio-terrorism, we have invested in the public health system by building more bio-safety level 3 and 4 laboratories including the latest BSL3 at George Mason University, we have expanded the CDC and built up epidemic centers at the WHO and elsewhere and we have improved some local public health centers. Most importantly, a network of experts at the department of defense, the CDC, universities and private firms has been created. All of this has increased the speed at which we can respond to a natural or unnatural pandemic.

In 2009, as H1N1 was spreading rapidly, the Pentagon’s Defense Threat Reduction Agency asked Professor Ian Lipkin, the director of the Center for Infection and Immunity at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, to sequence the virus. Working non-stop and updating other geneticists hourly, Lipkin and his team were able to sequence the virus in 31 hours. (Professor Ian Sussman, played in the movie by Elliott Gould, is based on Lipkin.) As the movie explains, however, sequencing a virus is only the first step to developing a drug or vaccine and the latter steps are more difficult and more filled with paperwork and delay. In the case of H1N1 it took months to even get going on animal studies, in part because of the massive amount of paperwork that is required to work on animals. (Contagion also hints at the problems of bureaucracy which are notably solved in the movie by bravely ignoring the law.)

It’s common to hear today that the dangers of avian flu were exaggerated. I think that is a mistake. Keep in mind that H1N1 infected 15 to 30 percent of the U.S. population (including one of my sons). Fortunately, the death rate for H1N1 was much lower than feared. In contrast, H5N1 has killed more than half the people who have contracted it. Fortunately, the transmission rate for H5N1 was much lower than feared. In other words, we have been lucky not virtuous.

We are not wired to rationally prepare for small probability events, even when such events can be devastating on a world-wide scale. Contagion reminds us, visually and emotionally, that the most dangerous bird may be the black swan.

The Great Relocation or the Great Stagnation?

From a very good and thoughtful post by Noah Smith, here is one set of excerpts but do read the whole thing:

The idea, in a nutshell, is that economic activity is relocating from rich Europe, America, and Asia to developing Asia faster than technological progress can replenish it…

Note that although this Great Relocation is an alternative to Tyler Cowen’s Great Stagnation, it does not preclude it. Lower productivity growth could coexist alongside agglomeration effects. Or…they might even go together. As I wrote in an earlier post, some “endogenous growth” theories suggest that the availability of cheap labor can reduce the incentives for innovation. If technological progress has stalled, it might just be because the Great Relocation has taken priority.

…So China “took our jobs.” But this was not due to their exchange rate policy, or their export subsidies, or their willingness to pollute their rivers and abuse their workers, although all these things probably speed the transition. They took our jobs because it made no sense for a farm like the U.S. to be building the world’s cars and fridges in the first place. Forcing China to revalue the yuan might slow the Great Relocation a little, but has zero hope of stopping it.

Arnold Kling has related posts as well, focusing on factor price equalization rather than relocation. A few points in response:

1. Median income begins to stagnate in 1973, before this trend is significantly underway.

2. I do not see these forces — however strong they may be (and I am not sure) — as separate from a stagnation hypothesis. If you read the first excerpted sentence, it compares the speed of the relocation to the speed of (American) technological progress. I am focusing on the latter deficiency, without pretending it is our only problem.

3. I find Smith’s policy suggestions intriguing. They include more immigration (which suddenly acquires a new urgency), more urban density (ditto), and better roads, to boost nation-wide agglomeration effects.

Assorted links

1. A new paper on Japanese monetary policy and why it didn’t work better (pdf).

2. Markets in everything (disgusting).

3. Bob Frank summarizes his new book on Darwin > Smith.

4. How is tennis spin changing? And how much are the chess pieces really worth?

5. Sending children through the mail (not the worst thing we do with them).

More pre-orders!

The Prague Cemetery, by Umberto Eco.

Reamde, by Neal Stephenson, out this Tuesday, no typo in the title, one positive review here.

I’ve never seen a year where the summer book titles were so empty and the fall season so full; what’s the economic explanation?

Do all serious economists favor a carbon tax?

Richard Thaler, Justin Wolfers, and Alex all consider that question on Twitter. I say no. While I personally favor such a policy, here are my reservations:

1. Other countries won’t follow suit and then we are doing something with almost zero effectiveness.

2. It may push dirty industries to less well regulated countries and make the overall problem somewhat worse.

3. There is Jim Manzi’s point that Europe has stiff carbon taxes, and is a large market, but they have not seen a major burst of innovation, just a lot of conservation and some substitution, no game changers. Denmark remains far more dependent on fossil fuels than most people realize and for all their efforts they’ve done no better than stop the growth of carbon emissions; see Robert Bryce’s Power Hungry, which is in any case a useful contrarian book for considering this topic.

4. Especially for large segments of the transportation sector, there simply aren’t plausible substitutes for carbon on the horizon.

5. A tax on energy is a sectoral tax on the relatively productive sector of the economy — making stuff — and it will shift more talent into finance and other less productive sectors.

6. Oil in particular will become so expensive in any case that a politically plausible tax won’t add much value (careful readers will note that this argument is in tension with some of those listed above).

7. A carbon tax won’t work its magic until significant parts of the energy and alternative energy sector are deregulated. No more NIMBY! But in the meantime perhaps we can’t proceed with the tax and expect to get anywhere. Had we had today’s level of regulation and litigation from the get-go, we never could have built today’s energy infrastructure, which I find a deeply troubling point.

8. A somewhat non-economic argument is to point out the regressive nature of a carbon tax.

9. Jim Hamilton’s work suggests that oil price shocks have nastier economic consequences than many people realize.

9b. A more prosperous economy may, for political and budgetary reasons, lead to more subsidies for alternative energy, and those subsidies may do more good than would the tax. Maybe we won’t adopt green energy until it’s really quite cheap, in which case let’s just focus on the subsidies.

10. The actual application of such a tax will involve lots of rent-seeking, privileges, exemptions, inefficiencies, and regulatory arbitrage.

It seems to me entirely possible that a serious economist would find those arguments hold the balance of power. In my view those points stack up against a) the problem seems to be worse than we thought at first, b) the philosophic “we are truly obliged to do something,” and c) “some taxes need to go up anyway” arguments.

I am in any case not an optimist on the issue and I consider my pessimism a more fundamental description of my views on the issue than any policy recommendation. If you study tech, you will see a bright present and also a bright future. If you study K-12 education, you will see a mixed to dismal present and a possibly bright future. If you study energy economics and the environment, you will see an OK present and a dismal future, no matter what policies we choose.

Assorted links

1. Splendid Charles Mann review of Hugh Thomas, a real zinger.

2. Is it illegal for a customer to write down prices in a store?

3. Trade politics in Middle Earth.

4. New book: Timothy Besley and Torsten Persson, Pillars of Prosperity: The Political Economics of Development Clusters, web page for the book is here.

5. How some regions are successfully reforming education.

6. Are autistics more likely to be atheists and agnostics (pdf)?