Month: April 2013

The Real Estate Commission Puzzle

Some seven years ago I wrote that the system of real estate commissions is horribly inefficient:

Consider, house prices are much higher in California than in Idaho but commissions are stable at around six percent. Thus, even though the realtor’s job, brokering a deal, is the same in California as in Idaho, a realtor in California will make much more per-house. As a result, there are far too many realtors in California and many of them will spend an entire year selling only a handful of houses. [At the height of the real estate boom in CA there were 437,000 real estate agents and only 680,000 home sales a year!, AT added 2013] Indeed, many realtor’s spend most of their time prospecting for clients rather than actually selling houses – this is a huge waste of resources. The same relationship holds over time as over space. That is, when house prices go up we don’t see a fall in commission rates. Instead, we see more entry. Since the same number of houses are being bought and sold, the extra realtors don’t make the buyer or seller better off and sadly the realtors aren’t better off either – instead the excess return is siphoned off in wasteful prospecting for clients. Unfortunately, no one really understands why commissions are stable.

When I wrote this in 2005 many commentators argued that fees would drop with the entry of online brokers. That has not happened. Indeed, as a recent piece in Bloomberg titled Why Redfin, Zillow, and Trulia Haven’t Killed Off Real Estate Brokers notes, the puzzle has in some ways gotten more difficult to understand. Today, lots of people use the internet to find homes by themselves, so brokers are doing less work, yet fees have by and large not fallen and most sales continue to use agents. Add to all this the Levitt and Syverson result that brokers sell houses too quickly and get lower prices than would be optimal for the seller and the puzzle deepens even further. As I wrote earlier the obvious answers don’t seem correct:

The answer is not monopoly. It’s very easy to enter the market for realtors. So why don’t commissions fall? One can certainly point to some restrictive practices by the NAR but I don’t think that is the whole or even the major part of the story. A clue to the puzzle is that we also see stable commission rates in law (contingency fees) and in services (tipping). Why is the appropriate tip 15% at an expensive restaurant and at a cheap restaurant? Does the tuxedoed waiter really have a harder job than the diner waitress? Maybe (indeed, I have argued along these lines elsewhere) but the commonality across these very different markets tells me something else is going on. Is it signaling? Would you distrust a realtor offering lower commissions? Again, maybe, but it’s hard to believe that with so much money at stake there aren’t enough people willing to take a risk on a discount realtor for long enough for reputations to be established. I think part of the problem in the realtor market is that other realtors can easily discriminate against discount brokers by pushing their clients one way or the other – that says the antitrust actions will probably not be very effective [and may help to explain why Zillow and Trulia which don’t compete with agents have been very successful while Redfin which offers more value but does compete with agents is still a very small player, AT 2013]. But this doesn’t explain stable commissions in law or waiting.

Hat tip: Newmark’s Door.

Robert Samuelson and Jeffrey Sachs on the budget

…government is slowly growing larger while — in many basic functions — it’s being strangled. This paradox, it seems, will be Obama’s questionable legacy.

President Barack Obama’s budget this week makes clear the real political equilibrium in the US. The federal government is shrinking. Discretionary spending in the new Obama budget would shrink to 4.9 per cent of gross domestic product in 2023, compared with 7.9 per cent of GDP in 2008. Both parties have signed on to this shrinkage. Neither will try to stop it.

Both over-personalize the result in the figure of President Obama. For reasons of mood affiliation, one calls it government growth and the other calls it government shrinkage, drawing on the same numbers. And both are basically correct.

Addendum: David Brooks weighs in on the same topic.

Is this grandma’s liquidity trap?

I say no and David Andolfatto agrees:

In grandma’s liquidity trap, the real interest rate is too high because of the zero lower bound. Steve [Williamson] argues that in our current liquidity trap, the real interest rate is too low, reflecting the huge world appetite for relatively safe assets like U.S. treasuries.

If this latter view is correct, then “corrective” measures like expanding G or increasing the inflation target are not addressing the fundamental economic problem: low real interest rates as the byproduct of real economic/political/financial factors.

I remain surprised at how many policy discussions fail to draw this basic distinction.

Hat tip goes to Mark Thoma.

Inform pedestrians, not drivers

From Sacha Kapoor and Arvind Magesan (pdf):

Most empirical studies on the role of information in markets analyze policies that reduce asymmetries in the information that market participants possess, often suggesting that the policies improve welfare. We exploit the introduction of pedestrian countdown signals – timers that indicate when traffic lights will change – to evaluate a policy that increases the information that all market participants possess. We find that although countdown signals reduce the number of pedestrians struck by automobiles, they increase the number of collisions between automobiles. We also find that countdown signals caused more collisions overall. The findings imply welfare gains can be attained by revealing the information to pedestrians and hiding it from drivers. We conclude that policies which increase asymmetries in information can improve welfare.

Hat tip goes to @m_sendhil.

Assorted links

Markets in everything

Hawkins’ clients are part of a growing trend: people paying to have their vacations professionally photographed.

Her clients say the results – clean, crisp, blur-free images ideal for holiday cards and brag books – are worth it.

Ugh says I, and the link is here, via Courtney Knapp.

Another way of thinking about the European economic collapse

Let’s start with a few claims that (most) people agree with:

2. The U.S. has higher income inequality than most of Europe and our high earners have done quite well for some time.

3. Many events happen in the U.S. first.

4. The U.S. is more flexible than most European economies, though not obviously more flexible than say Germany or Sweden.

OK, let’s tie those pieces together, but please keep in mind that I consider the following to be speculative.

IT and China, taken together, seem to imply a big whack to median income. This whack should be higher for the less flexible polities, and furthermore the wealthy and the well-educated in the U.S. get back a big chunk of that money through tech innovation and IP rights. Plus we’ve had some good luck with fossil fuels and even the composition of our agriculture. If you had a country without those high earners in the tech sector, and an inflexible labor market, those economies will have to contract and I don’t just mean in a short-term cycle. Equilibrium implies negative growth for those economies, at least for a while.

By how much? If the relatively flexible U.S. lost 8% of median income, perhaps Italy and Spain and Greece have to lose 15%, but with no offsetting major gains on the upper end of the income distribution. (How flexible is Ireland or for that matter France is an interesting question and so far the answer is not obvious.)

In sum, the less flexible European economies will lose at least 15% of their gdps, due to trade and technology.

There is then the question of what the path downwards will look like and feel like. Being in the eurozone makes adjustment much harder, and brings the doom more quickly, for reasons which are by now well-discussed.

The initial path looks like this. The real sectors of those economies start to appear weaker, and this sets off some deposit flight and also a credit contraction. AD and AS fall together and set off some further negative interactions. In the case of Greece the expectation of the country being “a European economy” gets replaced with the expectation of the country being “a Balkan economy,” to the detriment of investment of course. Along the way, the true nature of the EU political equilibrium is revealed, expectations of EU cooperation decline, and that sets off further AD and AS downward spirals.

Trying “austerity” will hasten the fall, but at the same time it is hard to see how an economy contracting by 15% could in the longer run keep its previous level of government spending, or for that matter find a “good” time to do fiscal consolidation. It will appear that “austerity” is more causally important than it really is.

All sorts of particular stories will get told along the way, including the austerity story. Those stories may look true, but ultimately they are more about timing and trajectory than about fundamental causes. What I call “time compression” will very often appear to be causality.

A lot of the problems caused by fiscal consolidation are in fact “sectoral shift” problems. For instance cuts in government spending lay off workers and the Mediterranean private sector — in the midst of a significant contraction and somewhat inflexible to begin with — is unlikely to rehire those workers. The fiscal policy advocates actually have an argument against their “let monetary policy do all the work” critics, although their obsession with AD prevents them from emphasizing the sectoral shift aspects of the fiscal story, which are in fact the paramount aspects.

How much has the Greek economy contracted already? (Hard to say with black markets and bad numbers but I think at least 20%). It is predicted that the Cyprus economy will collapse by 20% over the next three years. Think of their banking sector as unsustainable in the first place, but its decline being hastened rather suddenly by the curious structure of the euro and bank runs (again, time compression). It is not crazy to expect a ten percent permanent contraction for Italy and a very slow recovery for Spain after what is already a major contraction.

By the way, UK employment is now at an all-time high, as jobs have been reshuffled to lower-value service sector activities, and out of oil and finance. Does that fit the Keynesian story? Sorry people, but I have to say “no way.” Maybe the UK economy — which is flexible but not well-geared to export and to compete internationally — is on a path to lose five or ten percent of its gdp, with or without “austerity.”

Empirically, how would one distinguish this story from a more traditional Keynesian account?

1. Both imply that “austerity” appears causally correlated with bad outcomes. (By the way, ngdp targeting is still the way to go, although the lack of such a policy is a secondary or residual problem rather than the primary problem.)

2. Given the massively high unemployment we have seen, the Keynesian account would lead us to expect corresponding rates of price deflation comparable to those of the Great Depression, such as negative ten percent. We’re seeing rates of inflation between zero and two percent, with prices often continuing to move up. Inertia in sticky wages won’t get prices moving up like that, not if AD is supposedly collapsing to an extreme degree and as a driving force. This is pretty close to a “one fact” refutation of the simple Keynesian account. Study economic history all you want, 0-2% inflation may be suboptimal but the associated AD implications simply aren’t that bad, nor will adjusting for a few VAT hikes make it so. What we get is a series of blog posts measuring AD collapse by invoking surrealistic standards, and obscure concepts from modal logic, and failing to notice that price level behavior simply does not fit the story.

3. The Keynesian account implies a fairly quick bounce back for the plagued countries which (eventually) reject “austerity” and goose up AD. The theory here implies a quick bounce back for flexible economies, economies with IP and resources, but no rapid bounce back for the euro periphery, no matter what their policies, at least short of an extremely radical and probably impossible set of structural reforms, such as making Italy into Sweden. In any case, this test has not yet been run as those countries are still on the downswing.

In this account, AD economics, including its Keynesian and neo-monetarist forms, is correct, but it is also far from the entire story.

The devil’s defense of Bitcoin volatility

Bitcoin is now 44 percent off its intraday high of $266.

Maybe it’s in the nature of Bitcoin to have volatile prices (and Megan comments here).

But that’s part of the point, isn’t it? (Have we ever posted on the two envelopes problem? I think so but I can’t find it through search.) Imagine you hold a currency which, over the next period will either double or halve in value. The expected return of such a Bitcoin is in fact (0.5 x .5) + (0.5 x 2) = 1.25.

What a good deal that is! Holding a single Bitcoin — a very volatile Bitcoin that is — seems like a lot of fun. It’s unlikely that simple risk aversion will take away the expected gain there.

Does this not mean that exchange rate variability is desirable per se, a kind of automatic utility machine? The party holding the other currency reaps a comparable gain from the ex ante volatility.

Fischer Black was obsessed with this problem for a few years, though I don’t think he ever quite nailed it. The mathematics behind Jensen’s Inequality are relevant here, but again that’s not the same as an explanation of the puzzle. My preferred path is to start with the Sumnerian “never reason from a price change” insight, but in any case this is a good brain teaser for your evening.

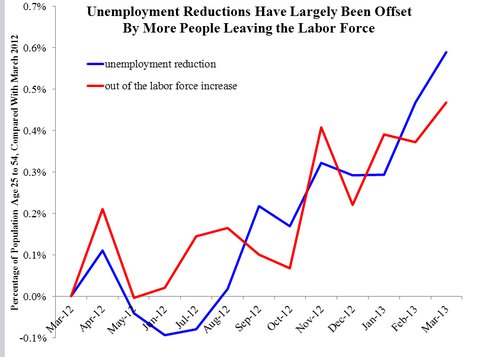

Why do the red and blue lines move so closely together?

That is from Casey Mulligan. What is actually the binding constraint in this labor market? Mulligan himself offers one hypothesis:

A significant part of the recent reductions in the unemployment rate may reflect movements of people between safety net programs rather than any significant change in their job-finding prospects.

Assorted links

1. Markets in everything: coffee cups made for squirrels. Why not?, I say. Given all the arbitrary causes which people take up, should we not in fact do just a small bit more for squirrels?

2. “Vervet monkeys solved a multiplayer coordination problem.”

3. Origami condoms.

4. Nine Queens do ferrets on steroids disguised as poodles.

5. Job openings but not everyone is getting hired, and data on Swedish female managers and professionals, compared to the U.S., older results on economists are here.

University of Chicago follows George Mason

The University [of Chicago] turns a former seminary into a new home for economics.

…When the refurbished building reopens in 2014, the economics department and Becker Friedman Institute for Research in Economics will have a spectacular space. Planned upgrades include a cloister café, LEED certification, high-tech classrooms in old library and chapel areas, and more.

Some of you will know that the Fairfax offices of Alex and me are in the space of a former church (scroll down to 1960)…

Here is more information and an interview with the architect. For the pointer I thank Mike Tamada.

Will Cyprus end up with free banking and a parallel currency (for a while)?

The lack of internal convertibility of euro notes (through the limitations on cash withdrawals and on electronic payments) will, if they persist for more than a few weeks, likely lead to a search for alternative media of exchange for internal transactions. IOUs of large, respected enterprises could for example be countersigned and start to circulate more widely as media of exchange and means of payment. This was the case, for instance, during the 1970 bank strike in Ireland, uncleared cheques were made negotiable (like bills of exchange) and pubs and shops served as credit verifiers. These could later develop into more full-fledged parallel currencies, if internal euro liquidity in Cyprus remains very scarce.

The rise of corporate savings as an issue

Andrew Smithers of Smithers & Co and Charles Dumas of Lombard Street Research have recently made much the same point. Japan’s private savings – almost entirely generated by the corporate sector – are far too high in relation to plausible investment opportunities. Thus, the sum of depreciation and retained earnings of corporate Japan was a staggering 29.5 per cent of GDP in 2011, against just 16 per cent in the US, which is itself struggling with a corporate financial surplus.

Japan’s economic system is a machine for generating high private savings. A mature economy with poor demographics cannot use these savings productively. As Mr Dumas notes, US gross fixed business investment has averaged 10.5 per cent of GDP over the past 10 years, against Japan’s 13.7 per cent. Yet US economic growth has much exceeded Japan’s. Japanese corporations must have been investing too much, not too little. It is inconceivable that raising the investment rate, to absorb more of the corporate excess savings, would not add to the waste.

That is from Martin Wolf. If you mix together a great stagnation, a shift of national income away from labor, higher income inequality, and the Ramsey rule, you arrive at some very strange economic states of affairs, ones I never thought I would see. I also note that these high rates of Japanese corporate investment are not exactly concordant with the naive old Keynesian model. I would suggest however that cutting the investment rate is not an answer per se, rather Japan needs a high investment rate but with better quality companies and investment opportunities, which will not prove easy to achieve.

Levitt and Fryer on race and IQ

From their April 2013 AER piece:

Analyzing these data, we find extremely small racial differences in mental functioning of children age 8 to 12 months. Absent controls, the mean white infant outscores the mean black infant by 0.055 standard deviation units — only a sliver of the one-standard-deviation racial gap typically observed at older ages. The raw scores for blacks are indistinguishable from Hispanics and Asians, who also slightly underperform whites. Adding interviewer fixed effects and controls for the child’s age, gender, socioeconomic status (SES) and prenatal circumstances further compresses the observed racial differences. With these covariates, we cannot reject equality in test scores across any of the racial/ethnic groups examined.

The piece is titled “Testing for Racial Differences in the Mental Ability of Young Children.” Versions of the piece are here, but I believe the final version is not yet in jstor.

Note that to the extent you treat parental IQ as affecting the IQ of the child through environment, these results are consistent with a wide variety of accounts of racial gaps in IQ. Still, there is no serious evidence, from these results, against the claim that the measured racial IQ gap is due to environment and environment alone.

Sentences about household wealth (Cyprus fact of the day)

On average, the wealthiest households are in Luxembourg, but Cyprus, which last month came close to a complete financial meltdown, was second.

That is from the eurozone. And this:

Median net wealth is the lowest in the bloc’s paymaster, Germany (51,400 euros), less than a third of that in Italy (173,500 euros) or Spain (182,700 euros), due to the relatively low level of home ownership in Germany.

As I’ve said many times in the past, much about the future will depend on whether wealth taxation turns out to be politically feasible to a greater degree than at present.