Month: April 2014

Speculative advice for (some) third world country checkpoints

John McAfee serves up many (speculative) points of interest:

The most powerful tool a traveler can possess is a Press card. It will allow you to completely bypass the “documentation” process if you have limited time or limited funds and don’t want to deal with it. I have dozens stashed in all my vehicles, in my wallet, in my pockets, in my boats.

I am paranoid about being caught without one when I need one. They have magical properties if the correct incantations are spoken while producing them. A sample incantation at a police checkpoint (this will work in any Third World country):

“Hi, I’m really glad to see you.” (produce the press card at this point). I’m doing a story on Police corruption in (fill in country name) and I would love to get a statement from an honest police officer for the story. It’s for a newspaper in the U.S. Would you be willing to go on record for the piece?” You can add or subtract magic words according to the situation. Don’t worry about having to actually interview the officer. No sane police person would talk to a reporter about perceived corruption while at the task of being perceived to be corrupt. He will politely decline and quickly wave you through. If you do find the rare idiot officer who wants to talk, ask a few pointed questions about his superiors and it will quickly awaken his sensibilities. He will send you on your way.

The press card is powerful, but has risks and limitations. Do not attempt this magic, for example, at a Federale checkpoint in Mexico on a desolate road late at night. You will merely create additional, and unpleasant work for the person assigned to dig the hole where they intend to place you.

Here is another bit:

Smile and, if possible, joke. Say something like: “I’d like to stay and chat but I’m in a hurry to meet a girl. Her husband will be back soon.” This will go a long way toward creating a shared communion with the officers and will elicit a shared-experience type of sympathy.

The advice is interesting throughout, but caveat emptor, please.

For the pointer I thank Patrick.

Economic policy of Modi bleg

I would like this post and its comments to be a useful resource for people looking to read about Modi’s economic policies, whether from the past in Gujarat or for his likely future in a national leadership post.

Please do offer your suggestions for reading, or put forward your own insights, economics and analytics only. If you are simply offering your opinion about Indian politics, or non-economic aspects of Modi, which occasion all sorts of non-factual emotional reactions, we will delete your comment in the interests of making the section useful and focused overall.

I thank you all in advance for contributing to this resource.

Alabama Texas fact of the day

“Revenues derived from college athletics is greater than the aggregate revenues of the NBA and the NHL,” said Marc Edelman, an associate professor at City University of New York who specializes in sports and antitrust law. He also noted that Alabama’s athletic revenues last year, which totaled $143 million, exceeded those of all 30 NHL teams and 25 of the 30 NBA teams.

Texas is the largest athletic department, earning more than $165 million last year in revenue — with $109 million coming from football, according to Education Department data. The university netted $27 million after expenses.

Other major programs such as Florida ($129 million), Ohio State ($123 million), Michigan ($122 million), Southern California ($97 million) and Oregon ($81 million) also are grossing massive dollars.

Those numbers of course are not counting the fundraising value of collegiate athletics. There is more here, via Michael Makowsky.

Here is our previous post on higher education and athletics.

Assorted links

1. The demand for coordinated sentiment.

2. A small idea to reduce distracted driving.

3. Which two sports have a smaller field than physics predicts? (hint: squash and Jai alai).

4. How U.S. A.I.D. is shifting its strategy.

5. Long-term unemployment and older workers.

Is the safety net failing the poor?

Catherine Rampell has an excellent blog post on this question, here is one bit:

Since the mid-1990s, the biggest increases in spending have gone to those who were middle class or hovering around the poverty line. Meanwhile, Americans in deep poverty — that is, with household earnings of less than 50 percent of the official poverty line — saw no change in their benefits in the decade leading up to the housing bubble. In fact, if you strip out Medicare and Medicaid, federal social spending on those in extreme poverty fell between 1993 and 2004.

Then, during the Great Recession and not-so-great recovery, automatic stabilizers kicked in and Congress passed new, mostly temporary, stimulus measures (such as unemployment-insurance benefit extensions). As a result, spending on the social safety net increased sharply and this time for a broader swath of Americans, including the very poor, “near-poor” and middle class. But it still rose more for people above the poverty line than it did for the very poor, Moffitt found.

Other public policies not captured by Moffitt’s calculations have also effectively diverted funds away from the very poorest Americans. Consider the rise of “merit-based,” non-means-tested financial aid at public colleges or the increasing number of tax breaks and loopholes known as “tax expenditures,” more than half of which accrue to the top income quintile.

And another:

Since the early 1990s, politicians have deliberately shifted funds away from those perceived to be the most needy and toward those perceived to be the most deserving. The bipartisan 1996 welfare reform — like the multiple expansions of the earned-income tax credit — was explicit about rewarding the working poor rather than the non-working poor. As a result, total spending per capita on “welfare” slid by about two-thirds over the past two decades, even as the poverty rate for families has stayed about the same. Many welfare reformers would consider this a triumph. If you believe many of the poorest families are not out of work by choice, though, you might have a more nuanced view.

Meanwhile, there is probably greater political cover for expanding the safety net for the middle class (that is, the non-destitute). As mid-skill, mid-wage jobs have disappeared — what’s known as the hollowing-out of the labor market — middle-class families have lost ground and are demanding more government help. These middle-class families, alongside the elderly, are also substantially more likely to vote than are the poor. The feds have whittled away at welfare, and (almost) nobody has said boo; touch programs that the middle class relies on, and electoral retribution may be fierce.

The piece is interesting throughout.

Will D.C. taxis mimic Uber with surge pricing?

There is now talk of this:

Washington could become one of the first U.S. cities to allow its cabdrivers to ignore their meters and adjust fares depending on demand.

D.C. Council members Mary M. Cheh (D-Ward 3) and David Grosso (I-At Large) have introduced legislation that would allow the city’s taxi drivers to embrace “surge pricing,” a practice used by popular mobile-dispatched car services such as Uber, in which prices are adjusted in real-time according to demand.

The council members say that the shift, which would apply only to passengers who use their smartphones or tablets to book a ride, will allow traditional cabs to better compete with new app-based ride services that have sprung up in the District and across the country.

The move could benefit riders by allowing them to comparison shop. But surge pricing has its critics, who say the practice can lead to gouging.

There is more here.

How much do Americans know about Ukraine?

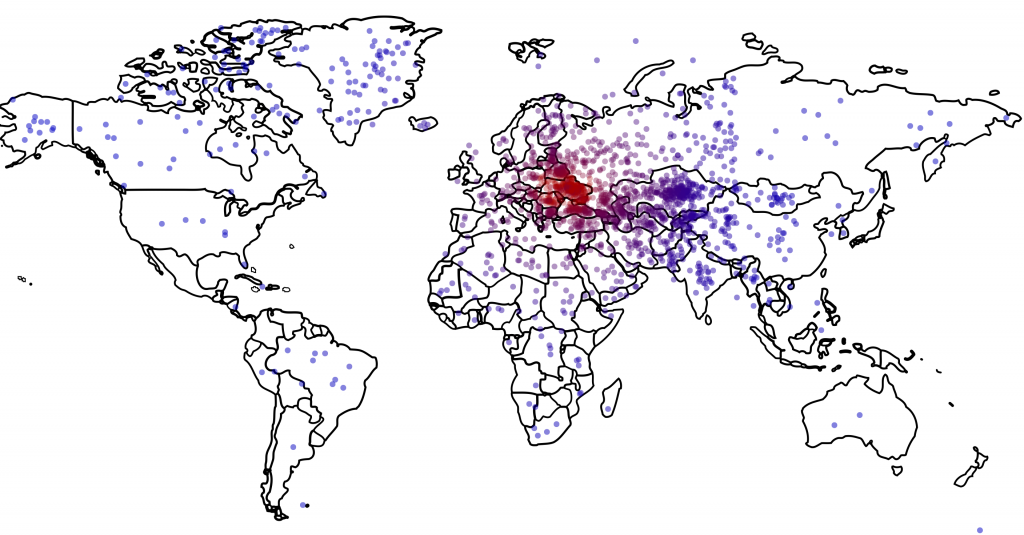

We found that only one out of six Americans can find Ukraine on a map, and that this lack of knowledge is related to preferences: The farther their guesses were from Ukraine’s actual location, the more they wanted the U.S. to intervene with military force.

…the median respondent was about 1,800 miles off — roughly the distance from Chicago to Los Angeles — locating Ukraine somewhere in an area bordered by Portugal on the west, Sudan on the south, Kazakhstan on the east, and Finland on the north.

That is from Monkey Cage, there is more here. The guesses look like this:

For points I thank Kevin Lewis and Samir Varma.

The INTIMACY project (there is no great stagnation)

INTIMACY is a high-tech fashion project exploring the relation between intimacy and technology. Its high-tech garments entitled ‘Intimacy White’ and ‘Intimacy Black’ are made out of opaque smart e-foils that become increasingly transparent based on close and personal encounters with people.

Social interactions determine the garmentsʼ level of transparency, creating a sensual play of disclosure.

INTIMACY 2.0 features Studio Roosegaardeʼs new, wearable dresses composed of leather and smart e-foils which are daringly perfect to wear on the red carpet. In response to the heartbeat of each person, INTIMACY 2.0 becomes more or less transparent.

There is more information here, and for the pointer I thank Samir Varma.

Assorted links

1. Children need to learn context to know when to stop.

2. What are the legal obstacles to becoming a new internet service provider?

3. Is the American language becoming more polite and considerate?

4. Can you read seriously online?

5. Why fewer people are dying in car crashes these days. And Toyota is reintroducing some humans to work with robots.

Higher education is spending more on athletics

From 2004 to 2011, community colleges’ inflation-adjusted educational spending — on instruction, public service and academic support — declined, while their athletic spending increased 35 percent per athlete, the report said. Overall spending per student grew 2.6 percent.

Inflation-adjusted athletic spending also increased, by 24.8 percent, at public four-year colleges in all divisions in those years, while spending on instruction and academic support remained nearly flat, and public service and research expenditures declined, the report said. Their overall spending per student grew 1.6 percent.

The fastest growth in athletic spending was at Division III schools without football programs, where median inflation-adjusted spending for each student-athlete more than doubled from 2004 to 2012.

There is more here, by Tamar Lewin, interesting throughout.

Which social groups and classes should fear higher price inflation?

Paul Krugman considers who is helped and hurt by higher rates of price inflation, and he sees the big losers as the wealthy oligarchs (and see his column today here). In contrast, I see the big losers as those with protected service sectors jobs who do not wish to have their contracts reset. If you are a schoolteacher, a nominal wage cut is likely to mean a real wage cut because you don’t have the power to renegotiate into a deal as good as the one you started with. The declining labor mobility of the United States in general means that workers are more vulnerable to higher rates of price inflation. A guy living in Cleveland who plans on leaving for Houston is probably less worried about nominal variables, because he will be doing a new contract negotiation anyway.

We all know that inflation is extremely unpopular with voters. We also observe that inflation remains extremely unpopular in a variety of northern European economies, which typically have more egalitarian distributions of income (though not always wealth) than does the United States. In any case the top 0.1 percent in those countries has less wealth per capita than in the U.S. and, at least according to progressives, less political influence too.

Of course the ability of inflation to erode rents is one of its virtues. The super-wealthy are often earning rents, but typically those rents are structured to be relatively robust to changes in nominal variables. For instance the rent might take the form of IP rights, or resource ownership rights. Simple loans of money, as we find in traditional creditor-debtor relationships, just aren’t monopolizable enough or profitable enough to be a major source of riches for the most wealthy.

I was puzzled by this comment on Krugman’s:

But there is one small but influential group that is in fact hurt by financial repression

which is just like what Hitler did to the Jews: again, the 0.1 percent.

People that wealthy can put their money into hedge funds, private equity, private capital pools, and the like. Of course there is risk involved but they have a chance as good as anyone to earn the highest rates of return prevailing in an economy, through creative uses of equity and on top of that very good accountants and tax lawyers. The very wealthy also have the greatest ability to hedge against inflation using derivatives and commodities, if they do desire.

In other contexts, Krugman (correctly) stresses that price inflation lowers the real exchange rate of a country (and thus is not neutral, supporting the view that nominal variables really do matter). So one big group of gainers from domestic inflation are those who invest lots of money overseas, wait for some inflation, and eventually convert their foreign currency holdings back into dollars for a very high net rate of return.

Which group of people might that be? The super wealthy of course. (This internationalization of returns for the super wealthy, by the way, is one big difference between current times and the 1970s.)

I am not suggesting that the very wealthy are out there pushing for higher inflation. But they are much more protected against such inflation than Krugman’s analysis suggests, and the middle class in protected service sector jobs is more vulnerable than is usually recognized. There is a reason why 4-6% price inflation has become the new third rail of American politics.

Addendum: Here are some related comments from Brad DeLong. I understand the very wealthy as believing (rightly or wrongly) that higher rates of price inflation increase economic uncertainty without providing much in the way of benefit for the real economy. So, given that belief, why should they favor higher price inflation? Since the status quo is based on low rates of price inflation, a switch to higher inflation would in fact disrupt markets (for better or worse), which would send a kind of self-validating short-run signal, at least apparently affirming this view held by the super wealthy that inflation will increase economic uncertainty.

Vox is up!

You will find the introductory video here.

Here is an explainer for Game of Thrones.

Here is Ezra on how politics makes us stupid.

Those two articles are very good, and “work” in the intended manner. Here is the regular home page www.vox.com.

Is it possible their real competition is Coursera?

Assorted links

1. The old version of China Star has reopened out near Fair Oaks under a new name.

2. Do selfies encourage more plastic surgery? And barter markets in everything: payments in selfies, Beyonce edition.

3. Mango trees and African sadness.

4. “Dad’s Resume.” An excellent piece.

5. How many people does it take to colonize another star system? (maybe more than you think, via The Browser)

*Flash Boys*, the new Michael Lewis book

For all the criticism the book has received, I liked and enjoyed it. It illuminates a poorly understand segment of the financial world, namely high-frequency trading, and outlines some of the zero- and negative-sum games in that world. The stories and the writing are very good, as you might expect.

It is a mistake to take the book as a balanced or accurate net assessment of HFT, but reading through the text I never saw a passage where Lewis claimed to offer that. Maybe the real objections are to be lodged against the 60 Minutes coverage of the book (which I have not seen).

Why not read a fun book on a fun and understudied topic? Just don’t confuse the emotional tenor of the stories with a final and well-reasoned attitude toward the phenomenon more generally. Surely you are all able to draw that distinction. Right?

Why are so many people still out of work?: the roots of structural unemployment

Here is my latest New York Times column, on structural unemployment. I think of this piece as considering how aggregate demand, sectoral shift, and structural theories may all be interacting to produce ongoing employment problems. “Automation” can be throwing some people out of work, even in a world where the theory of comparative advantage holds (more or less), but still this account will be partially parasitic on other accounts of labor market dysfunction. For reasons related to education, skills, credentialism, and the law, it is harder for some categories of displaced workers to be reabsorbed by labor markets today.

Here are the two paragraphs which interest me the most:

Many of these labor market problems were brought on by the financial crisis and the collapse of market demand. But it would be a mistake to place all the blame on the business cycle. Before the crisis, for example, business executives and owners didn’t always know who their worst workers were, or didn’t want to engage in the disruptive act of rooting out and firing them. So long as sales were brisk, it was easier to let matters lie. But when money ran out, many businesses had to make the tough decisions — and the axes fell. The financial crisis thus accelerated what would have been a much slower process.

Subsequently, some would-be employers seem to have discriminated against workers who were laid off in the crash. These judgments weren’t always fair, but that stigma isn’t easily overcome, because a lot of employers in fact had reason to identify and fire their less productive workers.

Under one alternative view, the inability of the long-term unemployed to find new jobs is still a matter of sticky nominal wages. With nominal gdp well above its pre-crash peak, I find that implausible for circa 2014. Besides, these people are unemployed, they don’t have wages to be “sticky” in the first place.

Under a second view, the process of being unemployed has made these individuals less productive. Under a third view (“ZMP”), these individuals were not very productive to begin with, and the liquidity crisis of the crash led to this information being revealed and then communicated more broadly to labor markets. I see a combination of the second and third forces as now being in play. Here is another paragraph from the piece:

A new paper by Alan B. Krueger, Judd Cramer and David Cho of Princeton has documented that the nation now appears to have a permanent class of long-term unemployed, who probably can’t be helped much by monetary and fiscal policy. It’s not right to describe these people as “thrown out of work by machines,” because the causes involve complex interactions of technology, education and market demand. Still, many people are finding this new world of work harder to navigate.

Tim Harford suggests the long-term unemployed may be no different from anybody else. Krugman claims the same. (Also in this piece he considers weak versions of the theories he is criticizing, does not consider AD-structural interaction, and ignores the evidence presented in pieces such as Krueger’s.) I think attributing all of this labor market misfortune to luck is unlikely, and it violates standard economic theories of discrimination or for that matter profit maximization. I do not see many (any?) employers rushing to seek out these workers and build coalitions with them.

There were two classes of workers fired in the great liquidity shortage of 2008-2010. The first were those revealed to be not very productive or bad for firm morale. They skew male rather than female, and young rather than old. The second affected class were workers who simply happened to be doing the wrong thing for shrinking firms: “sorry Joe, we’re not going to be starting a new advertising campaign this year. We’re letting you go.”

The two groups have ended up lumped together and indeed a superficial glance at their resumes may suggest — for reemployment purposes — that they are observationally equivalent. This discriminatory outcome is unfair, and it is also inefficient, because some perfectly good workers cannot find suitable jobs. Still, this form of discrimination gets imposed on the second class of workers only because there really are a large number of workers who fall into the first category.

Here is John Cassidy on the composition of current unemployment. Here is Glenn Hubbard with some policy ideas.