Month: February 2016

Scott Sumner responds on ngdp

Here is Scott’s lengthy response, do read the whole thing.

While I definitely favor having an ngdp futures market, and think it might improve monetary policy, its existence would not change (at all) any of the basic issues in my previous post. Closer to the central point I think is Scott’s claim: “Any “real shock” that reduces NGDP expectations because the Fed responded passively is also a monetary shock.” For me that is a real shock with insufficient monetary accommodation, not a “real shock,” as Scott gave it quotation marks, and also not a monetary shock. I prefer not to smush real and monetary shocks together in that fashion, and I think some ngdp theorists are trying to claim an explanatory victory by fiat by doing so. I do not think this matters for policy, and as I’ve stated I am very sympathetic to market monetarist recommendations. But in terms of explaining downturns, again, I think they are trying to claim some victories by fiat.

Wednesday assorted links

1. Is sexism rampant on GitHub?

2. Hendrik S. Houthakker makes a surprise appearance in this story about Pope John Paul II.

3. MIE: Kareem rug collection, from Minasian. For sale, he has good taste.

4. China capital flight of the day: lose a lawsuit on purpose.

5. Barter markets in everything: Mozart wrote music together with Salieri.

Former Dem CEAs Write Open Letter to Sanders

A strongly worded letter from Krueger, Goolsbee, Romer and Tyson to Sanders and his economic team chastising them for unrealistic, unscientific numbers. (No indent).

Dear Senator Sanders and Professor Gerald Friedman,

We are former Chairs of the Council of Economic Advisers for Presidents Barack Obama and Bill Clinton. For many years, we have worked to make the Democratic Party the party of evidence-based economic policy. When Republicans have proposed large tax cuts for the wealthy and asserted that those tax cuts would pay for themselves, for example, we have shown that the economic facts do not support these fantastical claims. We have applied the same rigor to proposals by Democrats, and worked to ensure that forecasts of the effects of proposed economic policies, from investment in infrastructure, to education and training, to health care reforms, are grounded in economic evidence. Largely as a result of efforts like these, the Democratic party has rightfully earned a reputation for responsibly estimating the effects of economic policies.

We are concerned to see the Sanders campaign citing extreme claims by Gerald Friedman about the effect of Senator Sanders’s economic plan—claims that cannot be supported by the economic evidence. Friedman asserts that your plan will have huge beneficial impacts on growth rates, income and employment that exceed even the most grandiose predictions by Republicans about the impact of their tax cut proposals.

As much as we wish it were so, no credible economic research supports economic impacts of these magnitudes. Making such promises runs against our party’s best traditions of evidence-based policy making and undermines our reputation as the party of responsible arithmetic. These claims undermine the credibility of the progressive economic agenda and make it that much more difficult to challenge the unrealistic claims made by Republican candidates.

Sincerely,

Alan Krueger, Princeton University

Chair, Council of Economic Advisers, 2011-2013

Austan Goolsbee, University of Chicago Booth School

Chair, Council of Economic Advisers, 2010-2011

Christina Romer, University of California at Berkeley

Chair, Council of Economic Advisers, 2009-2010

Laura D’Andrea Tyson, University of California at Berkeley Haas School of Business

Chair, Council of Economic Advisers, 1993-1995

Frances Coppola on negative interest rates

Negative rates are effectively a tax on deposits, and as such are intrinsically contractionary. They are a form of financial repression. As long as banks choose to absorb that tax themselves, those who pay that tax will effectively be bank shareholders and employees. But if banks choose to pass that tax on, it will be savers and borrowers who pay the tax. Would the increased economic activity that negative interest rates may generate be sufficient to offset the effect of this tax?

Alternatively, if we think of negative rates as a monetary operation rather than a tax, we can say that the central bank drains back a small proportion of the reserves it adds to the system through QE. This is monetary tightening. Again, would the increased economic activity generated by negative rates be sufficient to offset this effect?

There is more at the link, perhaps the best exposition of this argument I have seen to date. Here is also Jared Bernstein on negative rates. And Scott Sumner comments. And Izabella Kaminska comments.

Does paying cash now cut your health care bill?

This one is new to me, and I cannot vouch for it. Nonetheless I wondered if this report from Melinda Beck at the WSJ might be a positive sign:

Not long ago, hospitals routinely charged uninsured patients their highest rates, far more than insured patients paid for the same services. Now, in the Alice-in-Wonderland world of health-care prices, the opposite is often true: Patients who pay up front in cash often get better deals than their insurance plans have negotiated for them.

That is partly due to new state and federal rules aimed at protecting uninsured patients from price gouging. (Under the Affordable Care Act, for example, tax-exempt hospitals can’t charge financially strapped patients much more than Medicare pays.) Many hospitals also offer discounts if patients pay in cash on the day of service, because it saves administrative work and collection hassles. Cash prices are officially aimed at the uninsured, but people with coverage aren’t legally required to use it.

Here is the full story.

American Hispanics are doing better than we had thought

Many of the more successful individuals start identifying as “white,” which biases the measured results downward for the Hispanic category:

Because of data limitations, virtually all studies of the later-generation descendants of immigrants rely on subjective measures of ethnic self-identification rather than arguably more objective measures based on the countries of birth of the respondent and his ancestors. In this context, biases can arise from “ethnic attrition” (e.g., U.S.-born individuals who do not self-identify as Hispanic despite having ancestors who were immigrants from a Spanish-speaking country). Analyzing 2003-2013 data from the Current Population Survey (CPS), this study shows that such ethnic attrition is sizeable and selective for the second- and third-generation populations of key Hispanic and Asian national origin groups. In addition, the results indicate that ethnic attrition generates measurement biases that vary across groups in direction as well as magnitude, and that correcting for these biases is likely to raise the socioeconomic standing of the U.S.-born descendants of most Hispanic immigrants relative to their Asian counterparts.

Here is the NBER paper by Brian Duncan and Stephen J. Trejo, via Sam Bowman.

Bernanke and Kohn defend interest on reserves

On the potential for a contractionary impact of IOR, they write:

This claim, made even by some good economists, is puzzling. Before December, the Fed paid banks one-quarter of one percent on their reserves. If the Fed had not paid interest, the return to reserves would have been zero. Accordingly, the only potential loans that would have been affected by the Fed’s payment of interest are those with risk-adjusted short-term returns between precisely zero and one-quarter percent—surely a tiny fraction of the total. In fact, over the last four years bank lending has increased at about a 5 percent annual pace (including around a 7 percent annual rate the past two years), with only residential mortgage lending lagging in the aftermath of the housing bust.

There is more here. I cannot say I am convinced. I would focus not on the interstices of lending, but rather on expansionary pressures from the banking system. Without IOR, what do Fed models predict would have been the price level impact of those trillions of new reserves following 2008? (Note that at some margin banks can just convert those new reserves into dividends, without any additional lending, if they are so satiated with trillions of unwanted liquidity. I’m not saying it would happen that way, but think of that as a limiting case.) No, I’m not advocating hyperinflation, but less sterilization of those new reserves would have maintained aggregate demand at a higher level post-2008, boosting investment, output, and employment through a quite traditional channel, as advocated say by the market monetarists.

And note Bernanke and Kohn’s own argument, elsewhere in the post, that soaking up reserves by selling off the Fed’s portfolio may be impractical, disruptive, or too costly. Let’s say that’s true. By limiting its use of IOR, the Fed in essence would have made a more credible commitment that any increase in bank reserves is here to stay, rather than just sitting in a holding tank of sorts. No?

Bernanke and Kohn also rebut the common charge that interest on reserves is a subsidy to banks. They may be right, but they are arguing too hard for “it is not a subsidy at the current margin of further reserve extension,” and not sufficiently rebutting the possibility of an infra-marginal subsidy, initiated right after IOR.

So this is a very smart and well-argued post, as one would rationally expect, but I don’t quite think it lays one’s doubts to rest either.

Livestream for Nate Silver

Nate and I will be chatting at 3:30p.m., as part of Conversations with Tyler. You can find the LiveStream here, here are the questions you all have been suggesting, and the Twitter hashtag is #CowenSilver.

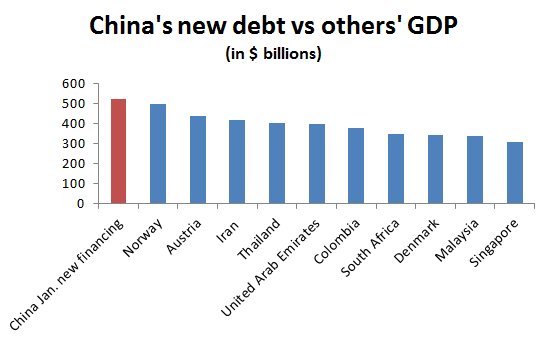

China fact of the day

If China’s new debt in January were a country, it would be the world’s 27th-biggest economy.

That is from Simon Rabinovitch.

p.s. they are not deleveraging.

p.p.s. my old method of clicking on the time stamp no longer creates a separate link for a tweet, how do I link to individual tweets now? Or does the algorithm no longer permit this?

Tuesday assorted links

1. Can a (British) dog fly a plane?

2. Left-wing economists skeptical of Bernie Sanders (NYT).

3. New survey paper on the causes and consequences of the Protestant Reformation; data-driven, economics of religion emphasis.

4. The self-driving office chair.

5. Will 3-D printing revolutionize the fashion industry?

6. Game-theoretic analysis of the politics of the Scotus nomination.

How tight is monetary policy now?, and some remarks on ngdp and market monetarism

I say “not that tight,” while leaving room open for the possibility that it should be looser.

What metrics might we look at? Federal funds futures no longer expect imminent further rate hikes from the Fed. Expected rates of price inflation have been very close to two percent. No matter what you think about the structural component of labor supply, cyclical unemployment has recovered a great deal over the last few years. And that is through the period of “taper talk” of almost two years ago. Consumer spending is doing OK, not spectacular but not cut off at the knees. And while in very recent times price expectations are headed downwards away from two percent, this seems to stem from negative real shocks, to which the Fed has responded passively (perhaps unwisely). That’s different than the Fed tightening. There was a quarter point rate hike from December, which is a small tightening for sure, but I don’t see much more than that.

So in sum, those data do not suggest severe monetary tightness, though again I am open to the argument that monetary policy should be looser.

By the way, I agree with Scott Sumner that we should not equate low interest rates with loose money. Tight and loose money are multi-dimensional, cluster concepts, especially post-2008, and require reference to a variety of variables. And if you are wondering, from this list of Lars Christensen monetary policy indicators I accept only #2, at least in a 2016 global setting where other real economies are volatile.

Given that I don’t see monetary policy as so tight right now, I suggested that if we have a recession it was likely to be a risk premium recession. The big uptick in gold prices is consistent with this view, though hardly proof of it.

So what is the context here? I am worried that if the United States has a recession this year (still unlikely, in my view, but maybe 20%?), that recession will be blamed on “tight money.”

To get more specific yet, I am very much a fan of the ngdp rule approach to monetary policy, but I am uncomfortable with one strand in market monetarist thought. I worry when low ngdp growth is blamed for low growth rates of real gdp.

Ngdp is an accounting summation, so I still want to know the real cause of the slower growth in real gdp. Let’s unpack at the most basic level whether the active cause was Fed tightening on the nominal side, or instead a negative real shock, followed perhaps by excess Fed passivity. That is one reason why I think of it as information-destroying to cite ngdp as a cause of developments in rgdp.

More fundamentally, if a central bank is doing anything close to price inflation targeting, mentioning low ngdp and low real gdp growth rates is simply citing the same fact twice, or almost so, rather than explaining one variable with the other. Angus once called the ngdp invocation a tautology; I’m not sure that is the right terminology, but still I wish to look for independent, non-ngdp measures of monetary policy when deciding how to allocate the blame for a recession, to real or nominal factors.

For further context, I was disquieted by some recent Lars Christensen posts on monetary policy and the American economy. I read him as “revving up” to blame a possible recession on tight U.S. monetary policy. I don’t think he provides much evidence that money is tight enough to cause a recession, other than citing the deterioration of some real variables.

I would encourage market monetarists to define — now — how tight or loose monetary policy really is. Then stick with that assessment, based on whatever variables you consulted.

A year from now, I won’t count it if you say a) “well, ngdp growth is down, money was tight, therefore real gdp growth rates fell. Tight money must have been the problem because low rates of ngdp growth are tight money.”

I would count it if you say something like b): “the dollar shock [or some other factor] was worse than the Fed had thought. That started to push us into recession. The Fed should have loosened, but they didn’t, and so the slide into recession continued, when the Fed could have moderated it somewhat by pursuing an ngdp target.” (By the way, read Gavyn Davies on the strong dollar issue. Alternatively, here is a Marcus Nunes take which I think is citing ngdp in exactly the way I am worried about.)

I also would count it if you said “I see the Fed tightening a lot right now, a recession is likely coming,” although I might dispute your evidence for that tightening.

Here is a recent Scott Sumner post, mostly about me. It’s basically taking the other side of what I have been arguing, and I would suggest simply disaggregating the ngdp terminology into a more causal language of nominal and real shocks. Surely there are other independent, ex ante signs for judging the tightness of monetary policy, rather than waiting for ngdp figures to come in, which again is citing a transform of the real gdp growth rate as a way of explaining real gdp.

I find these issues come up many, many times in market monetarist writings. I think they have basically the right policy prescription, and could provide the world with billions or maybe even trillions of dollars of value, if only policymakers would listen. But I also think they are foisting a language of causality on the business cycle problem which the rest of economic discourse does not easily absorb, and which smushes together real and nominal shocks into a lower-information accounting variable, namely ngdp, and then elevating that variable into a not entirely deserved causal role. We ought to talk in terms of ex ante, independent measures of monetary policy looseness, not ex post measures which closely resemble indirect transforms of real gdp itself.

That, in a nutshell is why, although I usually agree with the market monetarists on policy, and their desire to lower the status of “hard money” doctrine within liberalism, and while I have long applauded and supported their efforts, I don’t call myself a market monetarist per se.

Addendum: Nick Rowe comments. And Marcus Nunes comments.

The biases in Chinese SOEs

Chinese state-owned acquirers often seem motivated by non-commercial impulses, which complicates matters. By carrying out directives to “go out and buy” businesses that fit with Beijing’s industrial policy, state-owned companies and even a few of their private counterparts win kudos in the Communist party hierarchy. That helps them tap into official largesse, such as approval for expansion plans and backing from state banks and capital markets.

“State-owned enterprises have high incentives to increase their size, and they use plans outlined by [government agencies] as weapons to expand both domestically and internationally,” says Victor Shih, professor at University of California San Diego. “The bigger they are, the more political weight and more room for rent-seeking can be enjoyed by senior management.”

That is from a longer and excellent FT feature story on Chinese SOEs.

Monday assorted links

1. Albatross!

2. Do economic recoveries die of old age? It doesn’t seem so. And Tim Taylor comments and teaches us the word “paraedolia”: “looking at randomness and perceiving patterns that aren’t really there.”

3. The future of higher ed: a mentor for every student.

4. More evidence that negative interest rates aren’t working. They are not just a reflection of bad conditions, the tax on intermediation seems positively harmful, and there are ways to run an expansionary monetary policy which don’t involve this tax.

The Sharks Get Stung

On Friday, Shark Tank, the investment television show, featured two nice ladies from Minnesota and their product Bee Free Honee, honee made from apples. Is cheap, vegan honee a good idea? Perhaps but I was less than convinced by one of the arguments the ladies made for their honee–it will save bees! The ladies argued that reducing the demand for honey will encourage bee farmers to not work the bees so hard thus increasing their numbers.

I was expecting the acerbic Kevin O’Leary to have a field day with this economic fallacy. Or maybe, I thought, Mark Cuban will throw a dash of common sense into the tank. But no, all the Sharks cooed about this mad scheme. So it is up to me.

I was expecting the acerbic Kevin O’Leary to have a field day with this economic fallacy. Or maybe, I thought, Mark Cuban will throw a dash of common sense into the tank. But no, all the Sharks cooed about this mad scheme. So it is up to me.

Reducing the demand for honey, reduces the demand for honey bees. A cheap, high-quality substitute for honey doesn’t mean a world of bees gently pollinating flowers in an idyllic landscape it means a beepocolypse. Bee free honee will save bees the same way the internal combustion engine saved horses.

Addendum 1: You may be concerned about colony collapse disorder. Well, the commercial beekeepers are even more concerned and they have been adapting to CCD and maintaining honey production and pollination services. In fact, there are more bee colonies in the United States today (latest data) than there have been anytime in the last 20 years. CCD is still a problem but it’s the demand for honey and pollination services that incentivizes solutions to the problem. Remember, without honey it’s only a hobby.

Addendum 2:Perhaps the ladies have a sophisticated position on the repugnant conclusion but I doubt it.

Hat tip: Max.

Eric Burroughs on Chinese capital flight

Thus, we can say: 1) outflows are sizable but exaggerated in reserves (Feb should be telling given EUR’s surge); 2) China paying down FX debt is part of the equation, so it’s not all hot capital flight; 3) China’s overall debt is a problem but mostly in its own currency, so it has more means of dealing with it than other EMs in the many well-known debt crises of the past 30–40 years. I’m still waiting for a good explanation of why China can’t monetize its local FX debt and not hobble households in the process.

Here is more, of interest thoughout (which is not quite the same as “interesting throughout”), Eric is less bearish than many, worth the read. That said, the latest trade data are not looking so good.

Hat tip goes to www.macrodigest.com.