Month: April 2017

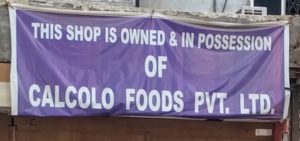

In India Possession is Maybe 6/10th of the Law

In India you will often see signs asserting Ownership and Possession on buildings and lots that are  unoccupied or under construction. The reason is not to stop squatters but rather to avoid the double selling problem. In the United States, it’s fairly easy to find out who owns a piece of land or even an expensive asset like a car. The land registry and titling system in India, however, is expensive and not always easy to check. As Gulzar Natarajan writes:

unoccupied or under construction. The reason is not to stop squatters but rather to avoid the double selling problem. In the United States, it’s fairly easy to find out who owns a piece of land or even an expensive asset like a car. The land registry and titling system in India, however, is expensive and not always easy to check. As Gulzar Natarajan writes:

For something so valuable, land records in most developing countries are archaic. No register, which reliably confirms title, exists anywhere in India. Small experiments in some states to build such register have not been successful. Existing registers suffer from problems arising from lack of updation, fragmentation of lands, informal family partitions, unregistered power of attorney transactions, and numerous boundary and ownership disputes. The magnitude of these problems gets amplified manifold in urban areas.

It’s possible, for example, for a family member to sell family land without anyone else knowing about it. In Muslim customary law, gifts made on the deathbed can override a will which (surprise!) tends to benefit late-stage caregivers. Verbal deals in general are not uncommon.

Indeed, without proper land registration it’s possible for an entirely unconnected person to sell land that he doesn’t own. Even if the real owners have some type of title, the ensuing court process between the real owners and those who thought or claimed they were the real owners will be time and wealth consuming. Forged documents are common. A large majority of all legal cases in India’s clogged court system are property disputes. The best thing is to occupy the land but if you can’t do that you want to signpost the land to make it as clear as possible who owns it so if someone is offered the land for sale they know who to call to verify.

Indeed, without proper land registration it’s possible for an entirely unconnected person to sell land that he doesn’t own. Even if the real owners have some type of title, the ensuing court process between the real owners and those who thought or claimed they were the real owners will be time and wealth consuming. Forged documents are common. A large majority of all legal cases in India’s clogged court system are property disputes. The best thing is to occupy the land but if you can’t do that you want to signpost the land to make it as clear as possible who owns it so if someone is offered the land for sale they know who to call to verify.

Signposting is an old device for avoiding the double spending/selling problem by making ownership claims public and verifiable. The blockchain ledger is a modern version. A land registry system on the blockchain could work and systems are being tested in Sweden, Georgia and Cook County. Implementing such systems, however, first requires that land be mapped and parceled–and in many states in India the last land surveys were done by the British before independence. Surveys are becoming easier with drones and automatic surveying but India’s land surveying, registering and titling system still has a long way to go.

Are weak ties less important for job-seeking?

…I argue that new technologies have changed the kinds of problems people face when searching for a job. The problem is no longer, as it was in the 1970s, discovering that the job opening exists in the first place. Instead, job seekers’ major problem is ensuring that someone notices their resume now that so many people are applying to every job opening. When you want your resume to be noticed, it turns out that workplace ties — people who can speak to what you are like as a worker — help white-collar job seekers much more than weak ties do (61 percent of my sample were helped by workplace ties, and 17 percent were helped by weak ties). This is not to say that Granovetter’s study is wrong, but rather that is is a grounded snapshot of a historical moment.

That is from the quite good and surprisingly substantive Down and Out in the New Economy: How People Find (or Don’t Find) Work Today, by Ilana Gershon.

Pay equality and treatment inequality within the corporation

One question is how much firms pay men and women, relative to their marginal products; here are some previous MR posts on that topic. A second question, neglected somewhat by economists (but not ignored more generally), is how men and women (and other genders) treat each other within the firm.

To go down this purely hypothetical path, let’s say a firm pays women their full and fair market value, but the firm is embedded in a city where men lord it over women, perhaps because of income inequality and unequal ratios in the dating market. Within that company, men may treat women in unfair ways. They may harass them, or simply listen to them less, or perhaps refuse to serve as mentors. The surrounding urban culture makes this a stable equilibrium, because the men in this company do not need the women so much for their preferred “total life portfolio” of gender relations. For purposes of contrast, if men need their particular workplace to date and marry suitable women, or even just have them as friends or mentors, those men will treat these women more courteously. (NB: is there an equilibrium where this attention leads to worse treatment? Maybe sometimes the women simply prefer to be ignored. I have heard that male tourists in Bangkok do not hit on the female tourists they meet there, for instance.)

The (fair) firm will fire egregious male offenders of the company’s norms, but some of these offenses are neither observable nor contractible. So imagine the firm setting the wage first, and then the men within that company claw back some of the employee surplus of the women by harassing those women.

The more fairly the company pays women, the more men within that company can harass the women, if only because the women are less likely to leave the company (the participation constraint).

So some of the benefit of paying women their fair share ends up distributed to those men, within the company, who wish to harass or otherwise mistreat those women. And of course the unfair treatment of women does not have to come from harassers, or even from men. It also could come from other women, or from relatively impersonal processes, such as inquiries and tribunals, which perhaps in some manner, possibly unintentionally, are less well geared to represents the interests of women. So you should interpret that word “harassment” in the broadest possible sense.

One prediction of this model is a good deal of harassment in sectors that have relatively strong pay equity norms. Furthermore, men bent on harassment or mistreatment of women may be among the biggest supporters of pay equity within their institutions.

The greater you think is the scope for potential male mistreatment of women, the weaker is the pecuniary case for pay equity norms, at least in a short-run, partial equilibrium setting (you might think in the longer run you can shift all the norms with tough, across-the-board enforcement).

Conversely, imagine you can shift the norms within a company so the male employees treat the female employees better. That weakens the pressures for the company to pay the women their full marginal products. Even a company bent on “being fair” may find it hard to spot the underpaid women, because they are not always leaving and revealing that better pay should be offered.

A broader point is that the ethos of a company can only deviate from the ethos of its geographic location by so much.

Of course that is all just in the model, the real world is quite different. In the real world, selection and clustering effects overwhelm the logic of compensating differentials, so there are good institutions and bad institutions. The good institutions pay the women what they deserve, and have stronger norms against harassment and bad treatment. All goes well there, and for that reason it is not hard to tell which are the good institutions and the bad institutions.

Do safe cars cost more to ensure?

New cars loaded with high-tech crash-prevention gear are having a perverse effect on car-insurance costs: They are soaring.

Safety features such as autonomous braking and systems to prevent drivers from drifting out of their lanes are increasingly available on vehicles rolling off assembly lines. Auto companies and third-party researchers say these features help prevent crashes and are building blocks to self-driving cars. But progress comes with a price.

Enabling the safety tech are cameras, sensors, microprocessors and other hardware whose repair costs can be more than five times that of conventional parts. And the equipment is often located in bumpers, fenders and external mirrors—the very spots that tend to get hit in a crash. Insurance companies, unwilling to shoulder all the pain, are passing some of the cost off to buyers.

Here is more from Christina Rogers and Leslie Scism at the WSJ.

Tuesday assorted links

1. Stripe is hiring an economist.

2. Might Seattle move away from NIMBY?

3. No strong evidence yet that smartphones are making us stupider.

4. Dolphin vs. octopus strategies.

5. Fatal injury aside, U.S. life expectancy is at the top.

6. Who is to blame for the judicial confirmation wars?

7. Tesla surpasses Ford in market value (NYT).

MRU video on The Great Reset

Why is authoritarianism on the rise?

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one bit from it:

You can scold the sympathizers for their naivete or illiberal tendencies, but there is a deeper truth. Individuals have a mimetic desire to copy or praise or affiliate what is perceived as successful, and a lot of our metrics of success have to do with power rather than freedom or prosperity. So if there is a powerful system on the world stage, many of us will be drawn to it and seek to emulate it, without always being conscious of the reasons for those attractions.

This process is actually not so different from how neoliberalism attracted greater support during the 1990s, when it was perceived as the major victor on the world stage. We neoliberals liked to think that the rest of the world “finally saw the light,” but a more sober retrospective assessment is that much of the popularity boom of neoliberalism was temporary, to be wiped out by status-lowering developments, including the financial crisis and slower real wage growth.

These chains of ideological influence can be remarkably indirect. For instance, it is commonly believed that the collapse of Soviet communism led to a softening of positions within the Irish Republican Army. It’s not that anyone ever expected the Soviets to intervene in the Irish conflict, but rather a role model of resistance had been taken away, and this ultimately made the peace process easier.

There is much more at the link, none of it especially cheery. By the way, I hope you know better than to read the piece as recommending authoritarian economic policy — stay awake!

Mark Koyama review of the Roman economy

Observe that Roman history leaves no traces of great mercantile companies like the Bardi, the Peruzzi or the Medici. There are no records of commercial manuals of the sort that are abundant from Renaissance Italy; no evidence of “class-struggle” as we have from late medieval Europe; and no political economy or “economics”, that is, no attempts to systematize one’s thoughts and insights concerning the commercial world. The ancient world, in this view, only superficially resembled that of early modern Europe. Seen from this perspective, the latter contained the potential for sustained growth; the former did not. Why is this?

The most obvious institutional difference between the ancient world and the modern was slavery. Recently historians have tried to elevate slavery and labor coercion as crucial causal mechanism in explaining the industrial revolution. These attempts are unconvincing (see this post) but slavery certainly did dominate the ancient economy.

In its attempt to draw together the various strands through which slavery permeated the ancient economy, Schiavone’s chapter “Slaves, Nature, Machines” is a tour de force. At once he captures the ubiquity of slavery in the ancient economy, its unremitting brutality—for instance, private firms that specialized in branding, retrieving, and punishing runaway slaves — and, at the same time, touches the central economic questions raised by ancient slavery: to what extent was slavery crucial to the economic expansion of period between 200 BCE and 150 AD? And did the prevalence of slavery impede innovation?

Here is the full piece, Mark is reviewing Aldo Schiavone’s The End of the Past.

Unruly Appalachia

For the oligarchs the greatest challenge has been getting Greater Appalachia into their coalition and keeping it there. Appalachia has relatively few African-Americans, a demographic fact that undermined the alleged economic and sexual “threat” raised by black empowerment. Borderlanders have always prized egalitarianism and freedom (at least for white individuals) and detested aristocracy in all its forms (except its homegrown elite, who generally have the good sense not to act as if they’re better than anyone else.) There was — and still is — a powerful populist tradition in Appalachia that runs counter to the Deep Southern oligarchs’ wishes.

That is from Colin Woodard’s American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America, a book worth rereading in light of recent events.

Monday assorted links

China Creates SEZ for Medical Tourism

The Chinese government have set up a special economic zone for medical tourism.

Hainan Boao Lecheng international medical tourism pilot zone, the first of its kind in the country, was approved by the State Council in 2013. It enjoys nine preferential polices, including special permission for medical talent, technology, devices and drugs, and an allowance for entrance of foreign capital and international communications.

The pilot zone also has permission to carry out leading-edge medical technology research, such as stem cell clinical research.

The zone, for example, offers a way to skirt the slow Chinese FDA (and presumably the slow US FDA as well).

Established in 2013, the Hainan program will open up new treatments–including Keytruda–to affluent Chinese residents who can afford the travel and medical costs, while other patients will have to wait for regulators to approve them. In recent years, mainland Chinese patients have increasingly traveled to Hong Kong or elsewhere in the face of lagging drug approvals by the China FDA and high treatment costs.

The zone is too small to have a significant impact on worldwide R&D but China’s original SEZs soon expanded. The SEZ could also encourage some interesting experiments. Keep an eye out for billionaires who travel to the island for a holiday and emerging looking younger and healthier.

What is the best way to attract high-skilled migrants?

Combining unique, annual, bilateral data on labor flows of highly skilled immigrants for 10 OECD destinations between 2000 and 2012, with new databases comprising both unilateral and bilateral policy instruments, we present the first judicious cross-country assessment of policies aimed to attract and select high-skilled workers. Points-based systems are much more effective in attracting and selecting high-skilled migrants than requiring a job offer, labor market tests, and shortage lists. Offers of permanent residency, while attracting the highly skilled, overall reduce the human capital content of labor flows because they prove more attractive to non-high-skilled workers. Bilateral recognition of diploma and social security agreements foster greater flows of high-skilled workers and improve the skill selectivity of immigrant flows. Conversely, double taxation agreements deter high-skilled migrants, although they do not alter overall skill selectivity. Our results are robust to a variety of empirical specifications that account for destination-specific amenities, multilateral resistance to migration, and the endogeneity of immigration policies.

I would urge a bit of caution, however. If you are Canada or Australia, and your country is not going to birth Google, you care most about the average skill level. If you are the United States, you might focus more on policies that boost the far right hand tail of value creation, because the benefits from that will be very high indeed. That means taking more chances on immigrants with an uncertain future but big potential upside, even if only with a small probability.

For the pointer I thank the excellent Kevin Lewis.

What I’ve been reading

1. Erica Benner, Be Like the Fox: Machiavelli’s Lifelong Quest for Freedom. A useful and readable introduction to the practical issues of Florentine politics and how they influenced the life and writings of Machiavelli.

2. Alan Taylor, American Colonies: The Settling of North America. Volume one of the Penguin History of the United States, this book is especially good at tying in “settlement issues” to later “governance issues.” It is compulsively readable and has an excellent annotated bibliography. Circa 1770, exports were about 10% of American gdp (p.311); today exports are a bit over 12% of gdp.

3. Holger Hoock, Scars of Independence: America’s Violent Birth. This is a look at the significance of violence in American history, focusing on the Revolution itself, and it is a good way to remind foreigners how screwed up (and dynamic) we are.

4. Arguments for Liberty, edited by Aaron Ross Powell and Grant Babcock. I do not think the arguments in this book succeed as arguments for liberty, with the exception of some of the utilitarian arguments, noting that I am only a “2/3s utilitarian.” Still, you get Eric Mack, Jason Kuznicki, Kevin Vallier, Neera Badhwar, Michael Huemer, and Jason Brennan, and so this is the rare edited volume that lives up to what you ideally might want it to be.

5. Jok Madut Jok, Breaking Sudan: The Search for Peace. I’ve read a few books on South Sudan lately, to try to figure out, if only in broad terms, what is going on there. This is the one that actually does a good job explaining things! Above all else, I now have some sense of just how historically deeply rooted the current conflict is. Recommended.

Jonathan Schwabish, Better Presentations: A Guide for Scholars, Researchers, and Wonks, is specific in all the right ways, most of all when it comes to Powerpoint slides.

My colleague Philip E. Auerswald has just published the very useful The Code Economy: A Forty-Thousand Year History.

Sunday assorted links

1. The Silicon Valley quest to live forever.

2. How transparency kills information aggregation.

4. Petition to keep Barnes&Noble in Bethesda.

5. First issue of American Affairs.

6. Julia Galef defends rationalism (contra Tyler). Lots of Twitter debate on this too.

Indian Civil Society Pushes Back Against Abuse of Power

Abuse of power isn’t new to India but the latest scandal is taking a different turn.

Outraged at not getting premium seating, a member of parliament belonging to the Shiv Sena, a regional party in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ruling coalition, on Thursday refused to deplane after his flight landed in New Delhi.

After repeated entreaties to disembark, the MP allegedly beat an Air India employee and tried to throw him down the landing stairs.

With a sandal, Ravindra Gaikwad repeatedly hit a shift manager who was sent to calm him down, while threatening to throw the man off the aircraft, flag carrier Air India Ltd said in a statement the same day. Video of the incident showed him pushing the airline employee toward the door.

Air India said it had informed the MP’s staff in advance that the aircraft didn’t have a business class. The passenger was accommodated in the first row of the all-economy plane because he wanted to take that particular flight, the carrier said.

The MP later bragged that of course he had beaten up the Air India employee because he’s a Shiv Sena MP who doesn’t put up with disrespect.

“Yes. I hit him. I wanted to throw him out of the plane,” the Shiv Sena MP told TIMES NOW. “Is he really an officer. He is not even a buffalo cart driver. He doesn’t know how to deal with customers,”

[By the way, shabash! to the air India hostess who stops Gaikwad from pushing the other employee down the stairs and then gives Gaikwad a piece of her mind, “you’re a role model, no?” she says defiantly.]

Gaikwad is no stranger to abuse of power:

Gaikwad is no stranger to abuse of power:

Gaikwad has seven cases registered against him, including that of culpable homicide not amounting to murder and charges of stopping a public servant from performing his duty, his 2014 election affidavit showed. He was also involved in the infamous incident at the Maharashtra Sadan in New Delhi when he was among 11 Sena MPs who forced a Muslim worker to break his Ramzan fast [i.e. force fed him, AT]…The MPs were complaining of poor quality ‘chapati.’

Air India and its employee have registered a complaint with the Delhi police who have opened an investigation, it will be interesting to see what they do. Civil society, however, is making its views very clear. The Indian media are raking Gaikwad over the coals. The hashtag #GoonGaikwad is popular.

Even more important, Air India, the government owned airline, has refused to fly Gaikwad. Air India and its political masters have long engaged in a mutually profitable relationship of backscratching, featherbedding and kickbacking so for them to put their foot down even against this kind of outrage is remarkable. Moreover, in a show of solidarity, all of the private airlines have followed suit so Gaikwad has been reduced to trying to book flights under various aliases. He’s been stopped every time, however, and in the end he had to drive from Mumbai to Delhi (a nearly 900 mile trip).

This kind of pushback by civil society against the abuse of power is in many ways unprecedented in recent times. It’s an interesting marker of change in India.