Month: August 2021

Monday assorted links

1. Politically polarized depositors.

2. The sociability of giraffes (NYT).

3. Emily Oster on different relative risks to children. Recommended.

4. Dalibor on Hungary. And a wee bit more on Hungary on Covid.

5. Without a rational expectations assumption, fiscal policy doesn’t work so well at the lower bound.

The performance of the NIH during the pandemic in 2020

“A new research study by one of us and his Johns Hopkins colleagues found that of the $42 billion the National Institutes of Health spent on research last year, less than 2% went to Covid clinical research…

Here is the WSJ source. Here is the full report from Johns Hopkins, and here is the executive summary:

● Of the $42 Billion 2020 NIH annual budget, 5.7% was spent on

COVID-19 research

● Public health research was underfunded at 0.4% of the 2020 NIH

budget

● Only 1.8% of the 2020 NIH budget was spent on COVID-19 clinical

research

● Average COVID-19 NIH funding cycle was 5 months

● Aging was funded 2.2 times more than COVID-19 research

● By May 1, 2020, 3 months into the pandemic, the NIH spent 0.05%

annual budget on COVID-19 research

● Of the 1419 grants funded by the NIH:

• NO grants on kids and masks specifically

• 58 studies on social determinants of health

• 57 grants on substance abuse

• 107 grants on developing COVID-19 medications

• 43 of the 107 medication grants repurposed existing drugs

Ouch. Here is a not entirely random sentence from the report:

The COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated the NIH institutional challenges and inability to reallocate funds quickly to

critical research.

Here is another damning sentence, though it damns someone other than the NIH:

…to date, no research has investigated NIH COVID-19 funding patterns to the best of our knowledge.

Double ouch. Might the NIH have too much influence over the allocation of funds to be investigated properly? Rooftops, people…

The American Academy of Pediatrics Tells the FDA to Speed Up and Stop Endangering Patients

The American Academy of Pediatrics has written a stunning letter to the FDA:

The American Academy of Pediatrics has written a stunning letter to the FDA:

We understand that the FDA has recently worked with Pfizer and Moderna to double the number of children ages 5-11 years included in clinical trials of their COVID-19 vaccines. While we appreciate this prudent step to gather more safety data, we urge FDA to carefully consider the impact of this decision on the timeline for authorizing a vaccine for this age group. In our view, the rise of the Delta variant changes the risk-benefit analysis for authorizing vaccines in children. The FDA should strongly consider authorizing these vaccines for children ages 5-11 years based on data from the initial enrolled cohort, which are already available, while continuing to follow safety data from the expanded cohort in the post-market setting. This approach would not slow down the time to authorization of these critically needed vaccines in the 5–11-year age group.

In addition, as FDA continues to evaluate clinical trial requirements for children under 5 years, we similarly urge FDA to carefully consider the impact of its regulatory decisions on further delays in the availability of vaccines for this age group. Based on scientific data currently available on COVID-19 vaccines, as well as on 70 years of vaccinology knowledge in the pediatric population, the Academy believes that clinical trials in these children can be safely conducted with a 2-month safety follow-up for participants. Assuming that the 2-month safety data does not raise any new safety concerns and that immunogenicity data are supportive of use, we believe that this is sufficient for authorization in this and any other age group. Waiting on a 6-month follow-up will significantly hinder the ability to reduce the spread of the hyper infectious COVID-19 Delta variant among this age group, since it would add 4 additional months before an authorization decision can be considered. Based on the evidence from the over 340 million doses of COVID-19 doses administered to adults and adolescents aged 12-17,as well as among adults 18 and older, there is no biological plausibility for serious adverse immunological or inflammatory events to occur more than two months after COVID-19 vaccine administration.

In my many years of writing about the FDA, I can’t recall a single instance in which a major medical organization told the FDA to use a smaller trial and speed up the process because FDA delay was endangering the safety of their patients. Wow.

The invisible graveyard is invisible no more.

Immigration encouragement as the new form of hybrid warfare?

Baltic officials say his [Lukashenko’s] latest tactic is to offer migrants from Iraq, Syria or several African countries a package that includes passage to the Lithuanian border. More than 4,000 migrants have crossed into Lithuania this year alone, more than 50 times the number that entered last year.

Rinkevics said this was “a very clear case of hybrid warfare” by deliberately using migration to target the EU and Lithuania. “The migrants are actually being used as the weapon. The longer we live in this 21st century, the scarier it becomes. Things that we couldn’t imagine that could be used, they are being used,” he said.

Here is the full FT piece, unsettling throughout.

People want predictability in their moral partners

Across six studies (N = 1988 US residents and 81 traditional people of Papua), participants judged agents acting in sacrificial moral dilemmas. Utilitarian agents, described as opting to sacrifice a single individual for the greater good, were perceived as less predictable and less moral than deontological agents whose inaction resulted in five people being harmed. These effects generalize to a non-Western sample of the Dani people, a traditional indigenous society of Papua, and persist when controlling for homophily and notions of behavioral typicality. Notably, deontological agents are no longer morally preferred when the actions of utilitarian agents are made to seem more predictable. Lastly, we find that peoples’ lay theory of predictability is flexible and multi-faceted, but nevertheless understood and used holistically in assessing the moral character of others. On the basis of our findings, we propose that assessments of predictability play an important role when judging the morality of others.

Here is the full piece by Martin Harry Turpin, et.al., via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Sentences to ponder

…participants who trust science are more likely to believe and disseminate false claims that contain scientific references than false claims that do not. Second, reminding participants of the value of critical evaluation reduces belief in false claims, whereas reminders of the value of trusting science do not. We conclude that trust in science, although desirable in many ways, makes people vulnerable to pseudoscience.

Here is the full paper, via the excellent Kevin Lewis. That is only one (non-replicated) paper, but the point is worth keeping in mind nonetheless.

Sunday assorted links

1. Video on how Olympians are financed in the U.S.

2. Where are the brick-laying robots?

3. More detail on Iceland. And NHS waiting times may not return to normal until 2025.

4. Interview with Francois Balloux.

5. A contrarian view on regulating crypto, probably wrong.

6. I understand the aesthetic value of constraint, but does “race walk” really make sense as an Olympic sport? (video)

Words of wisdom (from Ross Douthat)

Which is part of how a figure like Orban becomes appealing to American conservatives. It’s not just his anti-immigration stance or his moral traditionalism. It’s that his interventions in Hungarian cultural life, the attacks on liberal academic centers and the spending on conservative ideological projects, are seen as examples of how political power might curb progressivism’s influence.

Some version of this impulse is actually correct. It would be a good thing if American conservatives had more of a sense of how to weaken the influence of Silicon Valley or the Ivy League, and more cultural projects in which they wanted to invest both private energy and public money.

But the way this impulse has swiftly led conservatives to tolerate corruption, whether in their long-distance Hungarian romance or their marriage to Donald Trump, suggests a fundamental danger for cultural outsiders. When you have demand for an alternative to an oppressive-seeming ideological establishment, but relatively little capacity to build one, the easiest path often leads not toward renaissance, but grift.

Here is more from the NYT, mostly about Hungary. I think the same is true for Covid policy, by the way. It is hard for people — of any persuasion — to admit they have utterly lost ideological battles, whether they are right or wrong. So if Covid fraudsters “hold out straws to clutch,” there will be a fair numbers of takers, most of all from those who have been losing the debates. (“Ah, but now we will fight on the ivermectin front…”) But it is better to be more realistic. Unfortunately, “We’ve lost this one, we need to go back to the drawing board and start over” is one of the hardest things for people to say to themselves.

What I’ve been reading

1. Richard Zenith, Pessoa: A Biography. 942 pp. of text, yet interesting throughout. Brings you into Pessoa’s mind and learning to a remarkable degree. (Have I mentioned that the world is slowly realizing that Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet is one of the great works of the century?) His favorite book was Dickens’s Pickwick Papers, and he very much liked Carlyle’s Sartor Resartus. This biography is also interesting about non-Pessoa topics, such as Durban, South Africa in 1900 (Pessoa did live there for a while). I am pleased to see Pessoa finally receiving the attention he deserves — definitely one of the books of this year. Here is a good review of the book. For a man who never had sex, this book covers his sex life a great deal! And what a short and lovely title, no long subtitle thank goodness.

2. Nicholas Wapshott, Samuelson Friedman: The Battle over the Free Market. Quite a good book, though it is interior to my current knowledge set and thus better for others reader than myself. Contrary to what I have read elsewhere, Wapshott points out that Samuelson did not support Nixon’s wage and price controls, but this LA Times link seems to suggest Samuelson thought they were a good idea?

3. Jamie Mackay, The Invention of Sicily: A Mediterranean History. While it was less conceptual than I might have preferred, this is perhaps the single best general history of Sicily I know of. Short and to the point in a good way.

4. N.J. Higham, The Death of Anglo-Saxon England. In 1066, five different individuals were recognized as de facto King of England — how did that come to pass? Why was Aethelred the Unready not ready? (He was only 12 when he assumed the throne, though much of the actual criticism concerned the later part of his reign.) I find this one of the most intelligible and conceptual treatments of Anglo-Saxon England out there. I don’t care what the Heritage Foundation says, beware Danish involvement in your politics!

Peter Kinzler, Highway Robbery: The Two-Decade Battle to Reform America’s Automobile Insurance System is a useful look at where that debate stands and how it ended up there. Here is a good summary of the book.

It does not make sense for me to read Emily Oster’s The Family Firm: A Data-Driven Guide to Better Decision-Making in the Early School Years, but it is very likely more reliable information than you are likely to get from other sources.

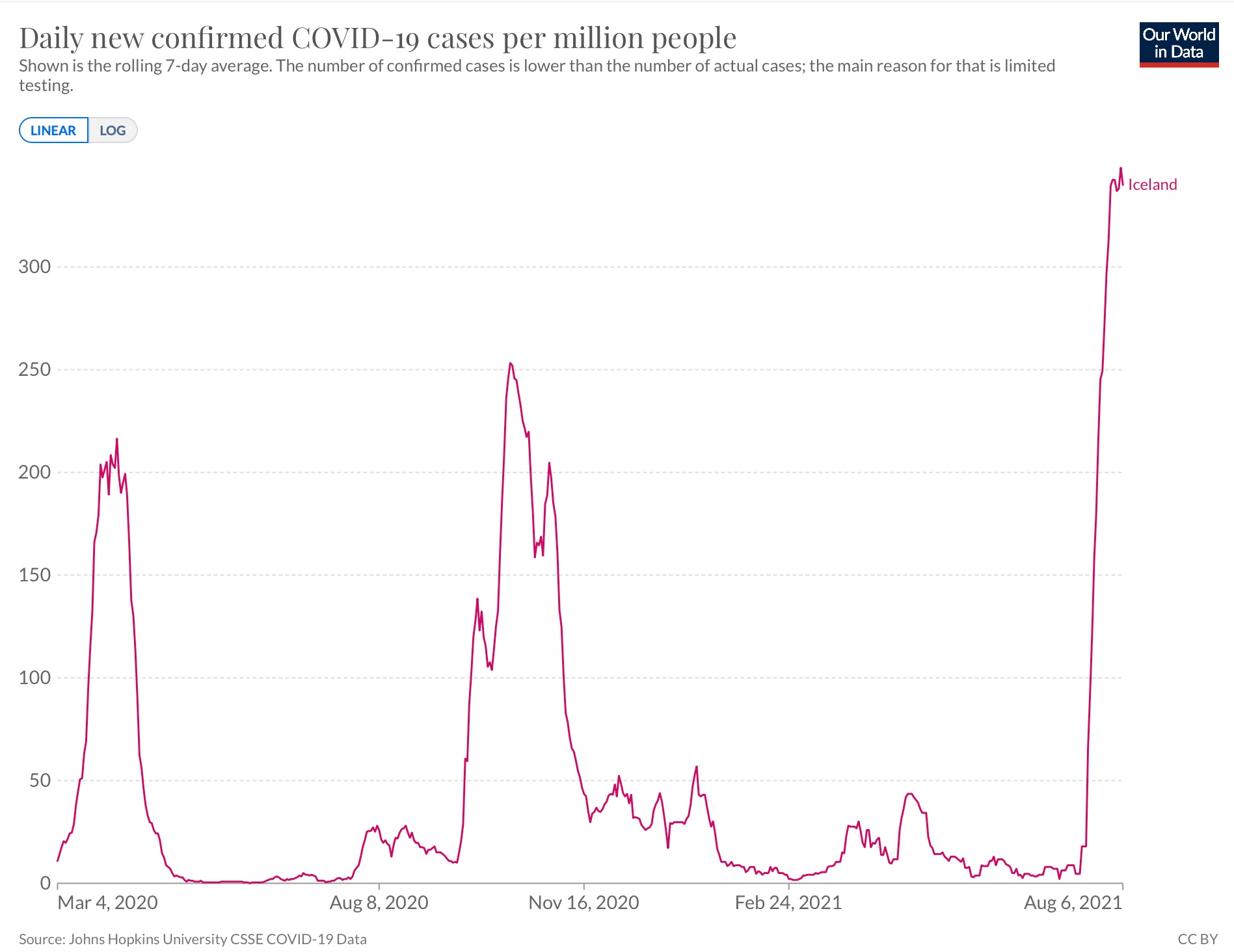

Iceland and Covid

As you may know, Iceland is one of the most fully vaccinated countries in the world:

All via Eric Topol. No, I am not arguing we should give up or stop looking for policy and most of all biomedical improvements. All the more reason to do so! But…this does indicate we will need to find some way of living with such case numbers, without falling apart and pulling the plug on economic activity.

Saturday assorted links

1. A dating thread.

2. “THINGS THAT I HAVE DONE THAT YOU (PROBABLY) HAVE NOT.” Is that the good life?

4. “Acrobatic squirrels learn to leap and land on tree branches without falling.”

5. The fight over crypto in the infrastructure bill.

6. Why doesn’t India win more Olympic medals? With apologies to Neeraj Chopra.

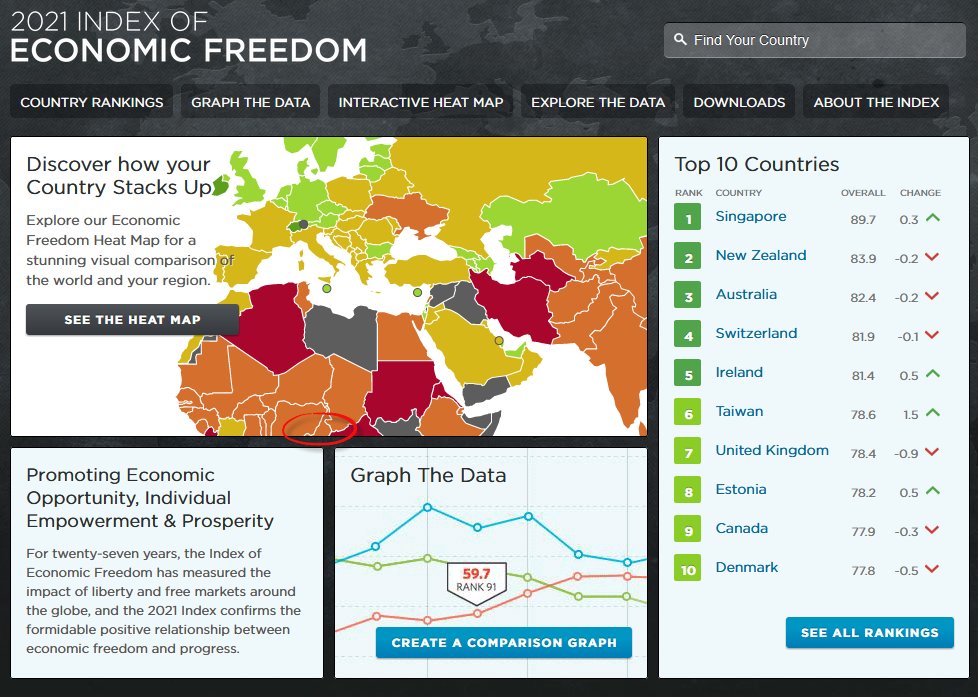

The Heritage Foundation Says the United States Should be More Like Denmark

The Heritage Foundation says the United States should be more like Denmark. On economic freedom of course. We are not number one. We are not even #10. Very sad.

Masks and the Delta variant

I haven’t seen any systematic, data-based investigation of how well cloth masks work against the Delta variant, and it is too early to expect it. Nonetheless I tried to do some simple mental modeling of my own.

We do know that the viral load from Delta is much higher. That could make masks less effective, because perhaps they cannot stop the spewer from spreading the virus so easily. (Oddly, you don’t see many people admitting such an effect might be possible, as this seems to be a politically incorrect idea to present.)

Yet there is a countervailing factor. The Delta variant spreads far more rapidly than “classic Covid.” So a given “small effect” of a mask is more important. It used to be that a mask (sometimes) stopped the spread to one person, who in turn might spread to 1.3 others. Now, if your mask stops the spread to that person, it might be stopping the subsequent spread to seven other people (we don’t know the exact number, but yes I have heard “seven” bandied around as a possibility).

To be clear, in this scenario masks are still less effective than before in preventing Covid spread. But the rate of return on wearing a mask, relative to no mask, can be higher. It is simply that the whole curve has shifted downward in a disadvantageous way. But if the mask has any effectiveness at all, that effectiveness is now magnified greatly.

Under some plausible numbers the protective potency of wearing a mask might be about five times higher (seven divided by recent non-Delta R, or something like that). Unless masks are five times (or more) less effective in stopping spread, masking could become more important rather than less important.

But the net effect could go either way.

That said, seeing other people masked should make you feel less secure than it used to. The new potential upside “rate of return effect” from masking is choking off the greater second order effects of the more rapid spread. The “are you going to get Covid from this particular masked person near you?” calculus seems to be decidedly worse than before.

David Beckworth on Powell and the Fed

My colleague David Beckworth has a new NYT piece, here is one bit from it:

Jerome Powell’s political skills also helped bring about a truly historic change at the Federal Reserve in 2020. Under his guidance, the Fed became the first central bank to adopt a “makeup” policy, which requires it to correct for past misses in its inflation target. Central banks actually see a mild amount of inflation as a sign of a healthy, growing modern economy. Inflation, for example, typically runs below its target during recessions and therefore needs to temporarily run above 2 percent afterward to make up for the shortfall. This, in fact, is what the Fed has been attempting over the past year by maintaining its low interest rate target and large-scale asset purchases. This new framework allows the economy to run hot after a recession and make up for lost ground. It means a quicker return to full employment and a more rapid restoration of incomes.

There is much more at the link.

Is this the correct market price?

This is totally immoral of course, but I am wondering about the elasticity of demand here:

One math lesson Prof. Edward C. Ennels taught at Baltimore City Community College was, according to prosecutors, pretty simple: $150 for a C; $250 for a B; and $500 for an A.

And in some courses, an A could go for as little as $300.

Over the course of seven months last year, Mr. Ennels, 45, solicited bribes from 112 students, and received 10 payments from nine students, totaling $2,815, the Maryland attorney general, Brian E. Frosh, said in a statement on Thursday.

In another scheme, Mr. Ennels sold online access codes that enabled students to view instructional material and complete assignments, prosecutors said. From 2013 to 2020, he sold 694 access codes for about $90 each.

Mr. Ennels, a professor at the college for 15 years who served on the faculty senate’s Ethics and Institutional Integrity Committee, pleaded guilty on Thursday in Baltimore County Circuit Court to 11 misdemeanor charges, including bribery and misconduct in office, according to prosecutors and online court records.

He was sentenced to 10 years in prison with all but one year of the term suspended and to be served in a local jail. He was also ordered to pay $60,000 in restitution and will be on probation for five years upon his release.

Mr. Frosh said in his statement that Mr. Ennels employed “an elaborate criminal scheme to take advantage of his students,” including using multiple aliases to hide his identity.

In March 2020, Mr. Ennels sent an email using one of his aliases, “Bertie Benson,” to another of his aliases, “Amanda Wilbert,” prosecutors said in a statement. In the email, “Benson” offered to complete “Wilbert’s” math assignments, guaranteeing her an A for $300, prosecutors said.

Then, as “Wilbert,” Mr. Ennels forwarded that email to 112 students enrolled in a class that he was teaching, prosecutors said. “Ennels often haggled with students regarding the amount of the bribe, and set different prices based on the course and grade desired,” according to the statement.

Most students declined to pay the bribes and Mr. Ennels “often persisted, offering to lower the amount of the bribe or offering payment plans,” according to the statement.

According to the statement, one student rebuffed the $500 solicitation for an A by saying: “Oh I don’t have that sorry. I will be sure to keep studying and pass my exam.” Mr. Ennels’s response, according to prosecutors: “How much can you afford?”

That student ultimately paid a bribe, according to prosecutors, who did not say how much that particular student paid.

I guess he was wondering about the elasticity of demand too. Here is the full NYT story.