Month: May 2023

More persistence and propagation than you might think?

Macroeconomic cycles are much more self-reinforcing and correspondingly resistant to shocks and hence longer-lasting than what is commonly thought…

The key idea is that economic developments feature strong endogenous propagation mechanisms which yield endogenous cyclical behavior ala limit cycles.

And:

What is at heart of this behavior? There are three factors that the authors point towards. First is strategic complementarity between economic agents’ behavior, such as the fact that firms want to invest when other firms are investing. Second, you need inertia in individual behavior, so that rapid changes in behavior are costly. And finally, you need dependence on some stock variable such as aggregate amount of capital or durable goods. All of these requirements seem very realistic assumption about the real world.

What are the implications of such model? Among other things this means that in certain periods of time the economy is very robust to negative shocks, because these shocks do not have the power to overturn the forces (resulting from the strategic complementarity between agents) that are pushing economic activity higher. They might push us slightly lower for some period of time, but they don’t turn things completely around. And once their effect fades the economy continues in its previous trajectory. In a sense, this view suggests that economic cycles are more like a titanic.

It also means that there is certain dichotomy in terms of shocks. Shocks ranging in size from “small” to “large-but-not-gigantic” proportions do not change the underlying trajectory of the economy, unless we are already close to turning point in the limit cycle. Meanwhile, truly gigantic shocks, like the global financial crisis, are not just deviation from the medium-term trend defined by the limit cycle, but a change in the medium-term trend.

And in conclusion:

To summarize, the limit cycle view suggests that a powerful enough shock, such as the rebound when economies re-opened after the pandemic recession, can put us on a upward spiral, and that such spiral features such a strong self-reinforcing mechanisms that even large negative shocks cannot derail us. This in contrast to standard DSGE models that feature only relatively weak propagation of shocks, and, crucially, do not feature any medium-term cyclical behavior.

Here is much more from Kamil Kovar, a good and important post.

Kevin Bryan on LLMs and GPTs for economic research

Here is the talk. I am waiting for someone to do some background “anthropological” research and field work, and create a fully simulated economy of say a village of five hundred people. (It is not difficult to have LLMs simulate human responses in economic games.) After that, the social sciences will never be the same again.

Friday assorted links

1. Tymofiy Mylovanov on foreign aid in Ukraine.

2. The most beautiful post offices? Why are none of them recently built? Recommended.

3. The contrarian case for Pakistan’s upside.

4. AI girlfriends markets in everything. And LLM liability for financial advising — what is the right approach?

5. Florida insurance carrier update.

Substitutes Are Everywhere: The Great German Gas Debate in Retrospect

In March of 2022 a group of top economists released a paper analyzing the economic effects on Germany of a stop in energy imports from Russia (Bachmann et al. 2022). Using a large multi-sector mathematical model the authors concluded that if prices were allowed to adjust, even a substantial shock would have relatively low costs. In contrast, the German chancellor warned that if the Russians stopped selling oil to Germany “entire branches of industry would have to shut down” and when asked about the economic models he argued that:

[the economists] get it wrong! And it’s honestly irresponsible to calculate around with some mathematical models that then don’t really work. I don’t know absolutely anyone in business who doesn’t know for sure that these would be the consequences.

The Chancellor was not alone in predicting big economic losses; some studies estimated reductions in output of 6-12% and millions of unemployed workers. The key distinction between the economists and the others was in their understanding of elasticities of substitution. When the Chancellor and the average person think about a 40% reduction in natural gas supplies, they implicitly assume that each natural gas-dependent industry must cut its usage by 40%. They then consider the resulting decline in output and the cascading effects on downstream industries. It’s easy to get very worried using this framework.

When the economists replied that there were opportunities for substitution they were typically met with disbelief and misunderstanding. The disbelief stemmed from a lack of appreciation of the many opportunities for substitution that permeate an economy. In our textbook, Modern Principles, Tyler and I explain how the OPEC oil shock in the 1970s led to an increase in brick driveways (replacing asphalt) and the expansion of sugar cane plantations in Brazil (for ethanol production). Amazingly, the oil shock also prompted flower growers to move production overseas, as the reduction in heating oil costs from growing in sunnier climates outweighed the increase in transportation fuel expenses. While these examples highlight long-term changes, short-term substitutions are also possible, though their precise details are usually hidden from central planners and economists.

The misunderstanding came from thinking that we need every user of fuel to find substitutes. Not at all! In reality, as fuel prices rise, those with the lowest substitution costs will switch first, freeing up fuel for users who have more difficulty finding alternatives. Just one industry with favorable substitution possibilities, combined with a few moderately adaptable industries, can produce a significant overall effect. Moreover, there are nearly always some industries with viable substitution options. To see why reverse the usual story and ask, if fuel prices fell by 50% could your industry use more fuel? And if fuel prices fell by 50% are their industries that could switch into the now cheaper fuel?

The misunderstanding came from thinking that we need every user of fuel to find substitutes. Not at all! In reality, as fuel prices rise, those with the lowest substitution costs will switch first, freeing up fuel for users who have more difficulty finding alternatives. Just one industry with favorable substitution possibilities, combined with a few moderately adaptable industries, can produce a significant overall effect. Moreover, there are nearly always some industries with viable substitution options. To see why reverse the usual story and ask, if fuel prices fell by 50% could your industry use more fuel? And if fuel prices fell by 50% are their industries that could switch into the now cheaper fuel?

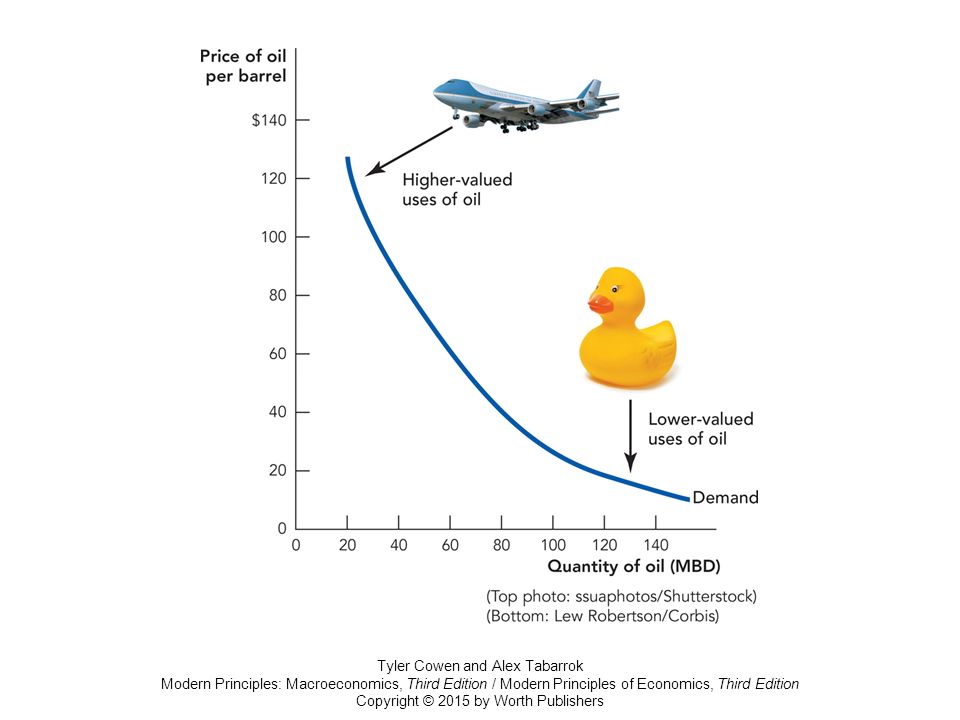

People often find it easier to imagine new uses rather than ways to reduce existing consumption. However, it is typically the new uses that are scaled back first. Tyler and I illustrate this with our jet and rubber ducky graph. Although jet aircraft won’t shift away from oil even at high prices, rubber (actually plastic) duckies, which are made from oil, can find substitutes–wood, for example–when oil prices rise. And if plastic ducky manufacturers cannot find substitutes, they go out of business, freeing up more oil for other uses. In this way, the market identifies the least valuable goods to cease production, another kind of substitution.

Substitution is a more nuanced concept than many people imagine. Here’s another example. Imagine that an economy has an energy-intensive goods producing sector and that there are few substitutes for the fuel used in this sector. Disaster? Not at all. We don’t need a fuel substitute, if we can substitute imports of the energy-intensive goods for domestically produced versions. Storage is also a substitute and notice that the more you substitute away from a fuel in final uses the greater the effective storage. If you use 1 gallon a day a 10 gallon tank lasts 10 days. If you use a quarter gallon a day it lasts 40 days. Everything is connected.

All of these myriad changes happen under the guidance of the invisible hand, i.e. the price system. Remember, a price is a signal wrapped up in an incentive. Thus Bachmann et al. wisely recommended letting energy prices rise to convey the signal and not insuring energy users so the incentive effects were fully felt on the margin.

So what happened? Gas from Russia was indeed cut very substantially but the German economy did not collapse and instead proved as robust as predicted, perhaps even more so. (The Chancellor’s predictions were off the mark but, to be fair, the government also did do a good job in sourcing new supplies and building reserves.) Moll, Schularick, and Zachmann have revisited the analysis and conclude:

The economic outcomes confirm the core theoretical argument that macro elasticities are larger than micro elasticities and that “cascading effects” along the supply chain would be muted as opposed to destroying the economy’s entire industrial sector. As foreseen, producers partly switched to other fuels or fuel suppliers, imported products with high energy content, while households adjusted their consumption patterns….Market economies have a tremendous ability to adapt that was widely underestimated. In addition, the German economics ministry (BMWK) was very successful in quickly sourcing gas supplies from third countries and building LNG capacity. Finally, it probably helped that German policymakers refrained from imposing a price cap on natural gas (like in many other European countries) and instead opted for lumpsum transfers based on households’ and firms’ historical gas consumption.

Hat tip: Alex Wollman.

Immigration and falling fertility rates

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

Some countries can be expected to keep their relatively restrictionist immigration policies. But in these countries, the population will become smaller and smaller while taxes on the young will get higher and higher, in part to pay for the retirements and health care of the elderly. The high taxes will in turn lower living standards, and that may depress fertility further yet.

A less obvious problem is that once nations enter the lower-population-higher-tax cycle, it may be very difficult for them to attract new migrants. If you were thinking of leaving your country, would you rather go to a wealthy country with higher tax rates, or one with lower tax rates? Especially if the country with higher taxes has a long tradition of not welcoming migrants, and you would be less likely to find any expatriates there? Besides which, due to their aging population, those countries may simply be boring, at least for young people.

The danger is that countries with more restrictionist immigration policies will get locked into low-migration outcomes for the foreseeable future, whether they like it or not.

Recommended.

Is it good to say “um”?

Disfluencies such as pauses, “um”s, and “uh”s are common interruptions in the speech stream. Previous work probing memory for disfluent speech shows memory benefits for disfluent compared to fluent materials. Complementary evidence from studies of language production and comprehension have been argued to show that different disfluency types appear in distinct contexts and, as a result, serve as a meaningful cue. If the disfluency-memory boost is a result of sensitivity to these form-meaning mappings, forms of disfluency that cue new upcoming information (fillers and pauses) may produce a stronger memory boost compared to forms that reflect speaker difficulty (repetitions). If the disfluency-memory boost is simply due to the attentional-orienting properties of a disruption to fluent speech, different disfluency forms may produce similar memory benefit. Experiments 1 and 2 compared the relative mnemonic benefit of three types of disfluent interruptions. Experiments 3 and 4 examined the scope of the disfluency-memory boost to probe its cognitive underpinnings. Across the four experiments, we observed a disfluency-memory boost for three types of disfluency that were tested. This boost was local and position dependent, only manifesting when the disfluency immediately preceded a critical memory probe word at the end of the sentence. Our findings reveal a short-lived disfluency-memory boost that manifests at the end of the sentence but is evoked by multiple types of disfluent forms, consistent with the idea that disfluencies bring attentional focus to immediately upcoming material. The downstream consequence of this localized memory benefit is better understanding and encoding of the speaker’s message.

That is from a recent paper by Diachek, E., & Brown-Schmidt, S., via Ethan Mollick.

Stanley Engerman, RIP

Here is one remembrance. I thank several MR readers for the pointer.

*The Middle Kingdoms: A New History of Central Europe*

An excellent book by Martyn Rady, here is the passage most relevant to the history of economic thought:

A Norwegian economist and his wife have published a line of bestsellers in the field of economics written before 1750. Top is Aristotle’s Economics. Composed in the fourth century BCE, it is still available in paperback. Martin Luther’s denunciation of usury (1524) is number three. But there, in the top ten, is an unfamiliar name — Veit Ludwig von Seckendorff (1626-1692), who was a government official in the duchy of Saxe-Gotha in Thuringia. Seckendorff’s German Princely State (Teutscher Fürsten-Staat, 1656) is a thousand-page blockbuster that went through thirteen editions and was in continuous print for a century. Although only ever published in German, it was influential throughout Central Europe, shaping policy from the Banat to the Baltic.

I enjoyed this sentence:

Besides his distinctive false nose (the result of a duelling accident), Tycho Brahe kept an elk in his lodgings as a drinking companion.

And yes the book does have an insightful discussion of Laibach, the Slovenian hard-to-describe musical band. You can buy it here.

Thursday assorted links

Free Insurance for Everyone!

President Biden says “We’re planning to make it mandatory for airlines to compensate travelers with meals, hotels, taxis, and cash, miles, or travel vouchers when your flight is delayed or cancelled because of their mistake.”

A classic example of the Happy Meal Fallacy:

Some restaurants offer burgers without fries and a drink. These restaurants cater to low-income people who enjoy fries and drinks but can’t always afford them. To rectify this sad situation a presidential candidate proposes The Happy Meal Act. Under the Act, burgers must be sold with fries and a drink. “Burgers by themselves are not a complete, nutritious meal,” the politician argues, concluding with the uplifting campaign slogan, “Everyone deserves a Happy Meal!”

But will the Happy Meal Act make people happy? If burgers must come with fries and a drink, restaurants will increase the price of a “burger.” Even though everyone likes fries and a drink they may not like the added benefits by as much as the increase in the price of the meal. Indeed, this must be the case since consumers could have bought the meal before the Act but chose not to. Requiring firms to sell benefits that customers value less than their cost makes both firms and customers worse off.

Almost everyone understands this when it comes to burgers and fries but make it burgers, fries and air miles and some people will think this is a good idea. To recap, requiring firms to sell benefits that customers value less than their cost makes both firms and customers worse off. And if customers value the benefits at more than the cost then that’s a profit opportunity and there is no need for a mandate.

How to improve education

We present results from large-scale randomized trials evaluating the provision of education in emergency settings across five countries: India, Kenya, Nepal, Philippines, and Uganda. We test multiple scalable models of remote instruction for primary school children during COVID-19, which disrupted education for over 1 billion schoolchildren worldwide. Despite heterogeneous contexts, results show that the effectiveness of phone call tutorials can scale across contexts. We find consistently large and robust effect sizes on learning, with average effects of 0.30-0.35 standard deviations. These effects are highly cost-effective, delivering up to four years of high-quality instruction per $100 spent, ranking in the top percentile of education programs and policies.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Noam Angrist, et.al.

Is Switzerland right-wing? (from my email)

Dear Tyler,

I came across this study today (https://serval.unil.ch/resource/serval:BIB_236420EB8209.P001/REF) that claims that Switzerland is one of the most right-wing (at least nominally) countries in Europe.The federal government has been in the hands of the right since 1848.The federal parliament is currently dominated by the right.26 out of 26 cantonal parliaments are controlled by the right.25 out of 26 canton governments (with the exception of the Jura) are in the hands of the right.Neither the parliament nor the national government has ever been controlled by the left.

How does it fit with your model of Switzerland?

Still an undeservedly overlooked country!

That is from Krzysztof Tyszka-Drozdowski.

Patrick Collison interviews Sam Altman

I haven’t heard this one yet, but if ever there was such a thing as self-recommending…link here. Hat tip Alex T.!

Open source chat, no censorship

Here it is, like it or not…

If you are looking for a chat LLM without any forced 'alignment' or 'moralizing' censorship, I recommend `WizardLM-13B-Uncensored` which was literally just released today.

Been playing with it all morning. It is my favorite open-source chat model so far.https://t.co/9vrPyktaIz https://t.co/xIthzHyUyK

— hardmaru (@hardmaru) May 10, 2023

Wednesday assorted links

1. Why not more solar power in Africa?

2. LLMs and intertemporal substitution of labor.

3. Nigeria travel notes. Long, fascinating, a bit too negative, recommended.

5. U.S. bank profits doing just fine, though slated to fall (FT).