Daron Acemoglu on what to do

In a piece entitled “The Real Solution is Growth,” he makes many good points, here is one:

Foster the commercialization of innovation. Much more can be done to facilitate this process. The Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 was only a small step toward encouraging commercialization of academic research. Even as the U.S. government is trying to cut spending, commercialization of new research would be one area deserving of new funding, particularly to ensure that this process does not undermine the greatest virtue of academic research, its openness.

He is also very good on patents, see this earlier Will Wilkinson blog post too.

Hat tip goes to ModeledBehavior on Twitter.

Non-Keynesian sentences to ponder

Unit labor costs, which are adjusted for efficiency gains, were projected to rise 2.4 percent, according to the survey median. Labor expenses in the first quarter were revised to 4.8 percent, the biggest gain since the fourth quarter of 2008, from a previously reported 0.7 percent advance.

Productivity, of course, is clocking in at lower than expected.

Assorted links

Is there a productivity crisis in Canada?

From Stephen Gordon, how about this?:

…an increase in business sector MFP [multi-factor productivity] of just over 10% in the span of almost 50 years is still not particularly impressive. And business sector MFP has fallen over the past ten years.

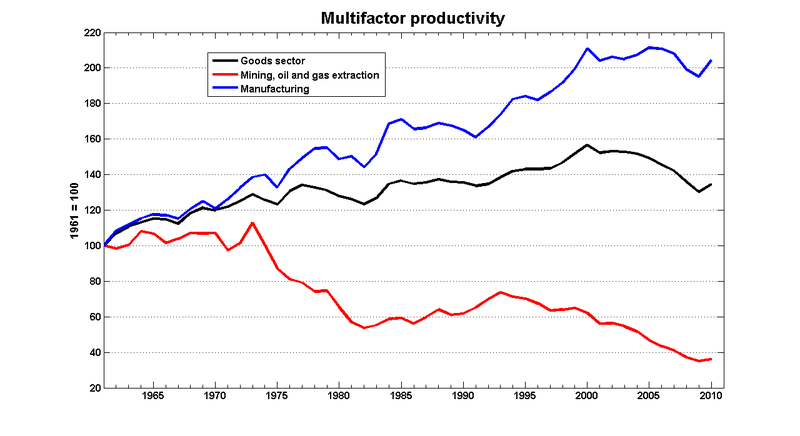

Yet the real story is more complicated and Gordon in fact prefers to dispense with the MFP metric. Let’s look at a stunning graph:

You can see that Mining and Extraction TFP takes a long plunge, even though Canada today prospers through selling natural resources. So what’s up? One of Gordon’s arguments against TFP is his claim that this graph implies earlier mining technologies were better than current mining technologies (unlikely), but that is a misunderstanding of what TFP measures. Think of TFP as trying to pick “the stuff we get for free through innovation.” Falling TFP in mining reflects Canada’s move from “suck it up with a straw” oil to complex, high cost extraction tar sands projects and the like. They have moved down this curve a long, long way.

Yet Canada still prospers: someone is willing to pay for all the time and trouble they put into extraction, because the other natural resource options are costlier at the relevant margin. Another way to make the point is that this graph, and the embedded story of productivity, is very bad news for someone, just not Canada, at least not so far.

You will see plenty of talk about the problem cases in the world economy, for instance Greece or Portugal. But arguably it is the success stories — Canada and Australia — which are scarier and more indicative of the true long-run problem.

The economics of riots

Has anyone linked to the DiPasquale and Glaeser 1996 paper on riots yet?

We examine the causes of rioting using international data, evidence from the race riots in the 1960s in the U.S., and Census data from Los Angeles, 1990. We find some support for the notions that the opportunity cost of time and the potential costs of punishment influence the incidence and intensity of riots. Beyond these individual costs and benefits, community structure matters. In our results, ethnic diversity seems a significant determinant of rioting, while we find little evidence that poverty in the community matters.

Here is a well-known political science paper on economic conditions and riots in India. Here is an economics paper on riots in India, AER 2008. Here is Alex’s piece on riots (gated). In London, the riots are getting closer to the LSE.

Just pre-ordered

Daniel Yergin, The Quest: Energy, Security, and the Remaking of the Modern World.

811 pp. of fun, fun, fun.

Markets in everything

In the UK, I have heard they prefer cricket, yet on Amazon sales of aluminum baseball bats are robust.

For the pointer I thank Chris F. Masse.

Assorted links

1. Black widow males prefer well-fed mates.

2. In which areas has consumer spending gone up since the recession?

3. Pregnancy envy and the death tax (pdf, strange but interesting essay by Dalton Conley).

4. Does P = NP (or not) matter for market efficiency? (video talk and linked paper)

5. Kenneth Rogoff on what to do.

6. An epistemic defense of the blogosphere (gated).

Which intellectuals have influence?

Ben Casnocha suggested to me that I have harsh standards. I don’t mean “influencing lots of other minds,” I mean changing the world. Here are a few intellectuals who have had real influence:

1. Jane Jacobs: City planners heed her strictures in many different locales, sometimes too much.

2. Rachel Carson, and numerous environmentalists: Obvious.

3. Milton Friedman: He inspired market-oriented reformers around the world, eased the way to floating exchange rates, helped legitimize early derivatives, and focused attention on monetary policy and away from fiscal policy, among other achievements.

What about today?

1. Peter Singer: Many fewer people eat meat and he has given the animal rights movement greater intellectual credibility.

2. Muhammad Yunnus: He popularized micro-credit and spread the notion to many countries, even though he is by no means its inventor.

3. Richard Posner: Many more judges use economic concepts when issuing judgments or writing up opinions.

Most of the people in this category have spent a big chunk of their lives pushing a single, fairly specific issue or method. You could add Bernanke (a special case, but still a yes), Charles Murray on poverty, and Germaine Greer. Art Laffer maybe. Friedman is a throwback to the time when generalists could be quite influential.

Who hasn’t had much influence over events? I would cite Jared Diamond, Richard Dawkins, Slavoj Žižek, Christopher Hitchens, Paul Krugman, Tony Judt, Noam Chomsky, Francis Fukuyama, Charles Taylor, Steven Pinker, Naomi Klein, and Niall Ferguson, among many others including virtually all economists.

Perhaps these individuals will have long-run influence on people’s broader views, and thus on longer-run events, but I wonder. Not everything feeds into a long and powerful stream, and every now and then there is a reset. We do not know, but we do know that some very focused individuals have had real influence.

I would put Esther Duflo, Jeffrey Sachs, Paul Romer, and Jacob Hacker (public option) in the “still have a good chance to have a big influence” category.

There is also the “futile crusaders” category, for instance Thomas Friedman for pushing for a centrist movement for green energy and Larry Lessig for IP reform and campaign finance reform, although of course subsequent events could upgrade them. We may well end up with green energy and IP reform but more likely as the result of technologies and market prices, rather than from successful intellectual battles.

Overall it is very hard to have much influence.

Why are bank stocks falling so rapidly?

Bank of America, the nation’s largest bank by assets, plunged 20 percent and Citigroup slid 16 percent, leading the KBW Bank Index (BKX) down 11 percent. It was the worst showing for the 24-company benchmark since April 20, 2009, when Bank of America told investors it was putting aside more money to cover a growing pool of uncollectible loans.

There is more here, and you can think of that price change as showing much higher tail risk. LinkedIn fell twenty percent (revenues are connected to recruiting), and Asian markets continue to fall. Treasury securities are stockpiled there, plus the general patina of American power and influence probably benefits Asia more than any other region. That’s the tragedy of this downgrade — the negative shock to American power and influence effect, not any enhanced probability of default. The CDS prices support that interpretation, but don’t neglect the broader geopolitical ramifications. Marketing and signaling really matter, and this remains a very definite step away from the idea of having another American Century. Contrary to Atrios, whether we like it or not, a lot of people — mostly not idiots — really do care what S&P thinks. I would have to put his quotation down as the least prophetic sentence of the year. Further equity price declines seem on the way.

The status of scientists

When asked to name a scientist, Americans are stumped. In one recent survey, the top choice, at 47 percent, was Einstein, who has been dead since 1955, and the next, at 23 percent, was “I don’t know.” In another survey, only 4 percent of respondents could name a living scientist.

Here is more.

Very good sentences

…in the wake of the weekend’s downgrade, we need them to govern as though that final victory might never quite arrive.

That is from Ross Douthat, here is more.

Assorted links

1. Can a woman lobby a guy she has already rejected?

2. The Baltimore Poe house might be closing.

3. What should Obama have done in 2009?

4. Are the Chinese liberals in decline? (link now fixed)

5. Scott Adams: “A lack of creativity always looks like some other problem. If no one invents the next great thing, it will seem as if the problem

is tax rates or government red tape or whatever we’re blaming this week.”

How to increase your reader downloads

From David McKenzie, at the World Bank, there is much more here. He also finds, as I had suspected, that a very small percentage of readers click through a link to read the abstract, maybe one or two percent.

The pithy essence

…as long as you have bad debt that is priced at par, you have an active crisis. To the extent that the ECB is trying to keep the price of weak-country debt close to par, it is not offering a credible solution. Uncertainty will prevail in the markets.

From Arnold Kling. You will note, of course, that this differs from Krugman’s multiple equilibria model.