The behavioral economics of pain

The two main lessons, as I read this paper, are a) pain is less bad when the sufferer can see the endpoint, and b) pain is less bad when the sufferer feels in control to some measure.

The concluding discussion of "happiness economics" is on the mark:

…my personal reflections are only in partial agreement with the literature on well being (see also Levav 2002). In terms of agreement with adaptation, I find myself to be relatively happy in day-to-day life – beyond the level predicted (by others as well as by myself) for someone with this type of injury. Mostly, this relative happiness can be attributed to the human flexibility of finding activities and outlets that can be experienced and finding in these, fulfillment, interest, and satisfaction. For example, I found a profession that provides me with a wide-ranging flexibility in my daily life, reducing the adverse effects of my limitations on my ability. Being able to find happiness in new ways and to adjust one’s dreams and aspirations to a new direction is clearly an important human ability that muffles the hardship of wrong turns in life circumstances. It is possible that individuals who are injured at later stages of their lives, when they are more set in terms of their goals, have a more difficult time adjusting to such life-changing events.

However, these reflections also point to substantial disagreements with the current literature on well-being. For example, there is no way that I can convince myself that I am as happy as I would have been without the injury. There is not a day in which I do not feel pain, or realize the disadvantages in my situation. Despite this daily awareness, if I had participated in a study on well-being and had been asked to rate my daily happiness on a scale from 0 (not at all happy) to 100 (extremely happy), I would have probably provided a high number, probably as high as I would have given if I had not had this injury. Yet, such high ratings of daily happiness would have been high only relative to the top of my privately defined scale, which has been adjusted downward to accommodate the new circumstances and possibilities (Grice 1975). Thus, while it is possible to show that ratings of happiness are not influenced much based on large life events, it is not clear that this measure reflects similar affective states.

As a mental experiment, imagine yourself in the following situation. How you would rate your overall life satisfaction a few years after you had sustained a serious injury. How would your ratings reflect the impact of these new circumstances? Now imagine that you had a choice to make whether you would want this injury. Imagine further that you were asked how much you would have paid not to have this injury. I propose that in such cases, the ratings of overall satisfaction would not be substantially influenced by the injury, while the choice and willingness to pay would be – and to a very large degree. Thus, while I believe that there is some adaptation and adjustment to new life circumstances, I also believe that the extent to which such adjustments can be seen as reflecting true adaptation (such as in the physiological sense of adaptation to light for example) is overstated. Happiness can be found in many places, and individuals cannot always predict their ability to do so. Yet, this should not undermine our understanding of horrific life events, or reduce our effort to eliminate them.

Here are Dan’s papers, and here. Here are Dan’s riddles.

Lancet

Left-wing bloggers, such as CrookedTimber, Brad DeLong, and Tim Lambert, are supporting the claim of about 600,000 extra deaths in Iraq. Jane Galt (scroll down for a few posts) and Steve Sailer raise some concerns.

I am a bit skeptical, but in any case the sheer number of deaths is being overdebated. Steve Sailer notes: "The violent death toll in the third year of the

war is more than triple what it was in the first year." That to me is

the more telling estimate.

A very high deaths total, taken alone, suggests (but does not prove) that the Iraqis were ready to start killing each other in great numbers the minute Saddam went away. The stronger that propensity, the less contingent it was upon the U.S. invasion, and the more likely it would have happened anyway, sooner or later. In that scenario the war greatly accelerated deaths. But short of giving Iraq an eternal dictator, that genie was already in the bottle.

If the deaths are low at first but rising over time, it is more likely that a peaceful transition might have been possible, either through better postwar planning or by leaving Saddam in power and letting Iraqi events take some other course. That could make Bush policies look worse, not better. Tim Lambert, in one post, hints that the rate of change of deaths is an important variable but he does not develop this idea.

We all know that the political world judges Iraq by the absolute badness of what is going on (which means Bush critics find a higher number to fit their priors), but that is an incorrect standard. We should judge the marginal product of U.S. action, relative to what else could have happened. (North Korea, and the UN response, will give us one data point from another setting.) In that latter and more accurate notion of a cost-benefit test, U.S. actions probably appear worst when deaths are rising over time, and hitting very high levels in the future.

Of course the rate of change of deaths is not exactly the proper variable. Ideally we would like some measure of the contingency of eventual total deaths, relative to policy. I am not sure what other proxies for that we might have.

Addendum: Let me put my comment up here on the front page: "Many of you are misreading the post by focusing only on the first case

of "bottled up killing," which is presented as only one of two

scenarios. Reread that if deaths are rising over time and possibly

contingent — and yes I do say this is the relevant and uncontroversial

fact — this suggests a very negative evaluation of Bush policies."

I don’t want to take the bait on why I am skeptical, the whole argument is that possible skepticism doesn’t have that much import once we consider the broader context of rising deaths and the possible contingency of those deaths.

Why no patent or copyright for new food recipes?

A loyal MR reader writes in:

Why do we have IPRs for literature, the arts and music but not for food dishes? Of course, I’m not talking about a copyright on the Ham & Cheese sandwich, I’m talking about innovative new dishes…I’m not arguing that we SHOULD have IPRs for food, just wondering what the big difference is (if any) between the culinary arts and other arts…I realize it would be difficult to enforce such rights at mom & pop type places…but it would be possible to enforce those rights at big name places and large chains.

Food relies so much on execution, or at the national chain level on marketing, that the mere circulation of a recipe does not much diminish the competitive advantage of the creative chef. Try buying a fancy cookbook by a celebrity chef and see how well the food turns out. (In contrast, an MP3 file is a pretty good substitute for a CD.) Most chefs view their cookbooks as augmenting the value of the "restaurant experience" they provide, not diminishing it. Furthermore industry norms, and the work of food critics, will give innovating chefs the proper reputational credit. It is not worth the litigation and vagueness of standards that recipe patents would involve.

Here is a recent article on recipe copyright.

Here is an academic paper on how norm-based copyright governs the current use of recipes. French chefs will ostracize "club members" who copy innovative recipes outright. Now the fashion industry wants IP protection as well.

Assorted

1. Mark Perry’s new economics blog.

2. Give oil money to the Iraqis? Maybe not.

3. Norway message in a bottle reaches New Zealand.

4. Topalov blunders a rook in sudden death play, Kramnik wins the title.

5. Robin Hanson on betting markets in CEO tenure.

Economist wins Nobel Peace Prize

The winner is Muhammad Yunus, economist (!) and founder of the micro-credit movement, along with his Grameen Bank. Here is the story. Here is his Wikipedia entry. Here is my New York Times column on micro-credit. Here is the best piece on what we know about micro-credit. Here is Yunus’s book on micro-credit, which also serves as a memoir and autobiography. It is a captivating and well-written story.

This is a wonderful choice. The funny thing is, they never would have considered this guy for the Economics prize.

I would write more, but a) read my column, and b) the Topalov-Kramnik sudden death speed chess tiebreakers are being played this morning, watch them live here. Susan Polgar offers running commentary here.

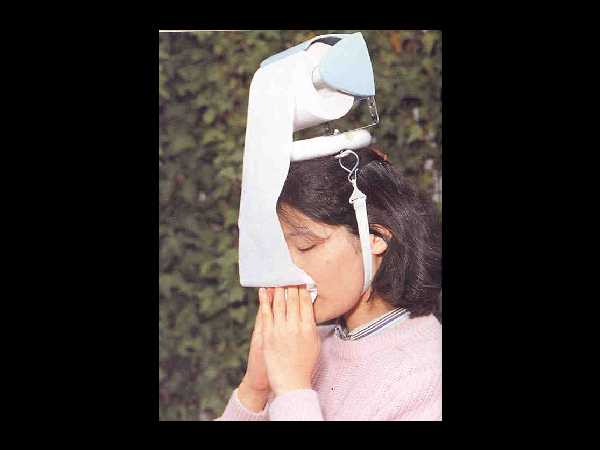

Markets in everything, Japanese edition

Here are seven more.

Why hasn’t South Africa done well?

Dani Rodrik reports:

South Africa has undergone a remarkable transformation since its

democratic transition in 1994, but economic growth and employment

generation have been disappointing. Most worryingly, unemployment is

currently among the highest in the world. While the proximate cause of

high unemployment is that prevailing wages levels are too high, the

deeper cause lies elsewhere, and is intimately connected to the

inability of the South African to generate much growth momentum in the

past decade. High unemployment and low growth are both ultimately the

result of the shrinkage of the non-mineral tradable sector since the

early 1990s. The weakness in particular of export-oriented

manufacturing has deprived South Africa from growth opportunities as

well as from job creation at the relatively low end of the skill

distribution. Econometric analysis identifies the decline in the

relative profitability of manufacturing in the 1990s as the most

important contributor to the lack of vitality in that sector.

Here is a non-gated version of the paper. The bottom line is that South Africa is de-industrializing.

Overlooked fiction from recent years

Slate.com polled several bloggers and booksellers, scroll down to find my pick. You are welcome to leave your ideas in the comments…

If you read only one book by Orhan Pamuk

The White Castle is short, fun, and Calvinoesque. Not his best book but an excellent introduction and guaranteed to please. Snow is deep, political, and captures the nuances of modern Turkey; it is my personal favorite. The New Life isn’t read often enough; ideally it requires not only a knowledge of Dante, but also a knowledge of how Dante appropriated Islamic theological writings for his own ends. My Name is Red is a complex detective story, beloved by many, often considered his best, but for me it is a little fluffy behind the machinations. The Black Book is the one to read last, once you know the others. Istanbul: Memories and the City is a non-fictional memoir and a knock-out.

Auction strategy and dating

In a standard English auction participants keep on bidding until one person is left with an unambiguously highest offer.

In a Dutch auction, which is used to sell tulips, the auctioneer starts out with a high price and keeps on lowering it until someone bites. The auction then ends.

A large literature considers the conditions under which these two approaches yield the same expected revenue.

In terms of dating, if you run an English auction you go out with many people, if not simultaneously then relatively closely bunched in time, and you stick with the one who offers the most. If you run a Dutch auction you signal clearly your standards (lowering the standards over time if need be), and stick with the first person who bites.

I believe that strongly Christian women are more likely to run a Dutch auction. Perhaps non-religious women are more likely to run Dutch auctions as they get older.

The economics literature suggests that if bidders are risk-averse, the Dutch auction is more likely to yield higher revenue (in the limiting case, grab quickly any positive consumer surplus, before it goes away). Alternatively, if the seller thinks that bidders would be more enthusiastic if they saw each other’s ongoing bids, this tends to encourage an English auction. In other words, hidden but not too hidden qualities encourage English auctions.

Here are other kinds of auctions.

Demand curves slope downward

A fact or two which Krugman leaves out about the Medicare drug coverage:

— If you don’t want a doughnut hole, you don’t have to have it.

> In every area, there are plans which cover drugs in that coverage

> gap.

>

> — There are also plans offering no deductible.

>

> — The original estimate of premium was $37. Then it went down to

> $32. In every state but Alaska, you can get coverage for less than

> $20. And in many states, there are plans for less than $10 month.

>

> — When the Medicare bill became law, people said no companies would compete for the Medicare drug coverage. That has turned out not to be true, and the competitive marketplace has helped drive down costs for taxpayers and those in Medicare.

Markets in time

…[the Chicago White Sox] have just announced

that for the next three seasons, their evening home games will begin at

7:11 p.m. instead of the customary 7:05 p.m. or 7:35 p.m. Why? Because

7-Eleven, the convenience store chain, is paying them $500,000 to do so.

That is from Stephen Dubner.

Markets in everything — Ur-edition

The source of the idea, and yes it is a video.

Why is it so hard to keep the house clean?

The simplest hypothesis is that we like to complain about a dirty or messy house but in fact we are observing an optimum. We just don’t want to put more time in.

The behavioral economist believes we are making the same mistake over and over again. What might that mistake be?

1. We clear away papers, books, and dirt, but we do not develop new systems for preventing their future accumulation. In other words, we reduce the immediate stress but discount the future stress of future dirtiness at too high a rate.

2. A free-rider problem, combined with ill-defined property rights, means that piles accumulate repeatedly. Cleaning is like removing a few cars from one lane of a two-lane highway. New cars (piles) step in quickly to fill the temporary gap. In a multi-person household, cleaning just shifts the traffic into different lanes rather than pricing the road.

A real solution might involve the random destruction or taxation of the property of other household members, so as to limit accumulation in the first place. Bonuses for savings could help as well, since savings are a relatively liquid and low storage cost means of carrying wealth.

3. We overrate the liquidity value of inventories. We want many things at hand which are of little or no use, perhaps because of an endowment effect. Most people should throw away anything they have not touched for the last three years.

4. Framing effects mean that we can get used to many kinds of messes. The real problems come from the people who keep their homes clean. Tax them and their cleanliness, for the same reasons that Bob Frank wishes to tax status goods.

Here is my previous post Tyler Cowen, Ramist. Here is my idea of how to clean up the house. Here is my post on the tennis ball problem.

Should pro-immigration forces favor a fence?

I am beginning to wonder:

Legislation passed by Congress mandating the fencing of 700 miles of

the U.S. border with Mexico has sparked opposition from an array of

land managers, businesspeople, law enforcement officials,

environmentalists and U.S. Border Patrol agents as a one-size-fits-all

policy response to the nettlesome task of securing the nation’s borders.Critics

said the fence does not take into account the extraordinarily varied

geography of the 2,000-mile-long border, which cuts through Mexican and

U.S. cities separated by a sidewalk, vast scrubland and deserts,

rivers, irrigation canals and miles of mountainous terrain. They also

say it seems to ignore advances in border security that don’t involve

construction of a 15-foot-high double fence and to play down what are

expected to be significant costs to maintain the new barrier.And, they say, the estimated $2 billion price tag and the mandate that

it be completed by 2008 overlook 10 years of legal and logistical

difficulties the federal government has faced to finish a comparatively

tiny fence of 14 miles dividing San Diego and Tijuana."This is the feel-good approach to immigration control," said Wayne

Cornelius, an expert on immigration issues at the University of

California at San Diego.

Construction of a fence, of course, would defuse many other pressures. Here is the full story.