Category: Economics

Paul Krugman on AI

Like previous leaps in technology, this will make the economy more productive but will also probably hurt some workers whose skills have been devalued. Although the term “Luddite” is often used to describe someone who is simply prejudiced against new technology, the original Luddites were skilled artisans who suffered real economic harm from the introduction of power looms and knitting frames.

But this time around, how large will these effects be? And how quickly will they come about? On the first question, the answer is that nobody really knows. Predictions about the economic impact of technology are notoriously unreliable. On the second, history suggests that large economic effects from A.I. will take longer to materialize than many people currently seem to expect.

…Large language models in their current form shouldn’t affect economic projections for next year and probably shouldn’t have a large effect on economic projections for the next decade. But the longer-run prospects for economic growth do look better now than they did before computers began doing such good imitations of people.

Here is the full NYT column, not a word on the Doomsters you will note. Could it be that like most economists, Krugman has spent a lifetime studying how decentralized systems adjust? Another factor (and this also is purely my speculation) may be that Krugman repeatedly has announced his fondness for “toy models” as a method for establishing economic hypotheses and trying to grasp their plausibility. As I’ve mentioned in the past, the AGI doomsters don’t seem to do that at all, and despite repeated inquiries I haven’t heard of anything in the works. If you want to convince Krugman, not to mention Garett Jones, at least start by giving him a toy model!

The Growing Market for Cancer Drugs

In my TED talk on growth and globalization I said:

If China and India were as rich as the United States is today, the market for cancer drugs would be eight times larger than it is now. Now we are not there yet, but it is happening. As other countries become richer the demand for these pharmaceuticals is going to increase tremendously. And that means an increase incentive to do research and development, which benefits everyone in the world. Larger markets increase the incentive to produce all kinds of ideas, whether it’s software, whether it’s a computer chip, whether it’s a new design.

…[T]oday, less than one-tenth of one percent of the world’s population are scientists and engineers. The United States has been an idea leader. A large fraction of those people are in the United States. But the U.S. is losing its idea leadership. And for that I am very grateful. That is a good thing. It is fortunate that we are becoming less of an idea leader because for too long the United States, and a handful of other developed countries, have shouldered the entire burden of research and development. But consider the following: if the world as a whole were as wealthy as the United States is now there would be more than five times as many scientists and engineers contributing to ideas which benefit everyone, which are shared by everyone….We all benefit when another country gets rich.

A recent piece in the FT illustrates:

AstraZeneca’s chief executive returned from a recent trip to China exuberant about an “explosion” of biotech companies in the country and the potential for his business to deliver drugs discovered there to the world….Many drugmakers are tempted by China’s large, ageing population, which is increasingly affected by chronic diseases partly caused by smoking, pollution and more westernised diets….the opportunity lies not just in Chinese patients, but also in the country’s scientists. “The innovation power has changed,” said Demaré. “It is no more ‘copy, paste’. They really have the power to innovate and put all the money in. There’s a lot of start-ups and we are a part of that.”

As I concluded my talk:

Ideas are meant to be shared, one idea can serve the world. One idea, one world, one market.

Population Dynamics and Economic Inequality

Broad movements in American earnings inequality since the mid-20th century show a correlation with the working-age share of the population, evoking concerns dating to the 18th century that as more individuals in a population seek work the returns to labor diminish. The possibility that demographic trends, including the baby boom and post-1965 immigration, contributed to the rise in inequality was referenced in literature before the early 1990s but largely discarded thereafter. This paper reconsiders the impact of supply-side dynamics on inequality, in the context of a literature that has favored demand-side explanations for at least 30 years, and a recent movement toward equality that coincides with the retirement of the baby boom generation, reduced immigration, and a long trend toward reduced fertility. Evidence suggests an important role for the population age distribution in economic inequality, and coupled with demographic projections of an aging population and continued low fertility portends a broad trend toward greater equality over at least the next two decades.

That is the abstract of a new paper by Jacob L. Vigdor. It was part of a recent NBER conference on fertility and demographics, kudos to Melissa Kearney (still underrated as a social force for good) and Philip B. Levine for putting it on.

Orwell Against Progress

Orwell was deeply suspicious of technology and not simply because of the dangers of totalitarianism as expounded in 1984. In The Road to Wigan Pier, Orwell argues that technology saps vigor and will. He quotes disparagingly, World Without Faith, a pro-progress book written by John Beever, a proto Steven Pinker in this respect.

It is so damn silly to cry out about the civilizing effects of work in the fields and farmyards as against that done in a big locomotive works or an automobile factory. Work is a nuisance. We work because we have to and all work is done to provide us with leisure and the means of spending that leisure as enjoyably as possible.

Orwell’s response?

…an exhibition of machine-worship in its most completely vulgar, ignorant, and half-baked form….How often have we not heard it, that glutinously uplifting stuff about ’the machines, our new race of slaves, which will set humanity free’, etc., etc., etc. To these people, apparently, the only danger of the machine is its possible use for destructive purposes; as, for instance, aero-planes are used in war. Barring wars and unforeseen disasters, the future is envisaged as an ever more rapid march of mechanical progress; machines to save work, machines to save thought, machines to save pain, hygiene, efficiency, organization, more hygiene, more efficiency, more organization, more machines–until finally you land up in the by now familiar Wellsian Utopia, aptly caricatured by Huxley in Brave New World, the paradise of little fat men.

What’s Orwell’s problem with progress? He is a traditionalist. Orwell thinks that men need struggle, pain and opposition to be truly great.

…in a world from which physical danger had been banished–and obviously mechanical progress tends to eliminate danger–would physical courage be likely to survive? Could it survive? And why should physical strength survive in a world where there was never the need for physical labour? As for such qualities as loyalty, generosity, etc., in a world where nothing went wrong, they would be not only irrelevant but probably unimaginable. The truth is that many of the qualities we admire in human beings can only function in opposition to some kind of disaster, pain, or difficulty; but the tendency of mechanical progress is to eliminate disaster, pain, and difficulty.

..The tendency of mechanical progress is to make your environment safe and soft; and yet you are striving to keep yourself brave and hard.

I will give Orwell his due, he got this right:

Presumably, for instance, the inhabitants of Utopia would create artificial dangers in order to exercise their courage, and do dumb-bell exercises to harden muscles which they would never be obliged to use.

Orwell’s distaste for technology and love of the manly virtues of sacrifice and endurance to pain naturally push him towards zero-sum thinking. Wealth from machines is for softies but wealth from conquest, at least that makes you brave and hard! (See my earlier post, Orwell’s Falsified Prediction on Empire). Orwell didn’t favor conquest but it’s part of his pessimism that he sees the attraction.

Another of Orwell’s tragic dilemmas is that he doesn’t like progress but he does favor socialism and thus finds it unfortunate that socialism is perceived as being favorable to progress:

…the unfortunate thing is that Socialism, as usually presented, is bound up with the idea of mechanical progress…The kind of person who most readily accepts Socialism is also the kind of person who views mechanical progress, as such, with enthusiasm.

Orwell admired the tough and masculine miners he spent time with in the first part of Wigan Pier. In the second part he mostly decries the namby-pamby feminized socialists with their hippy-bourgeoise values, love of progress, and vegetarianism. I find it very amusing how much Orwell hated a lot of socialists for cultural reasons.

Socialism is too often coupled with a fat-bellied, godless conception of ’progress’ which revolts anyone with a feeling for tradition or the rudiments of

an aesthetic sense.…One sometimes gets the impression that the mere words ‘Socialism’ and ‘Communism’ draw towards them with magnetic force every fruit-juice drinker, nudist, sandal-wearer, sex-maniac, Quaker, ‘Nature Cure’ quack, pacifist, and feminist in England.

…If only the sandals and the pistachio coloured shirts could be put in a pile and burnt, and every vegetarian, teetotaller, and creeping Jesus sent home to Welwyn Garden City to do his yoga exercises quietly!

What Orwell wanted was to strip socialism from liberalism and to pair it instead with conservatism and traditionalism. (I am speaking here of the Orwell of The Road to Wigan Pier).

It’s still easy today to identify the sandal wearing, socialist hippies at the yoga studio but socialism no longer brings to mind visions of progress. Today, fans of progress are more likely to be capitalists than socialists. Indeed, socialism is more often allied with critiques of progress–progress destroys the environment, ruins indigenous ways of life and so forth. A traditionalist socialism along Orwell’s lines would add to this critique that progress destroys jobs, feminizes men, and saps vitality and courage. Thus, Orwell’s goal of pairing socialism with conservatism seems logically closer at hand than in his own time.

The incidence of loans for graduate education

In 2006, the federal government effectively uncapped student borrowing for graduate programs with the introduction of the Graduate PLUS loan program. Access to additional federal loans increased graduate students’ borrowing and shifted the composition of their loans from private to federal debt. However, the increase in borrowing limits did not improve access to existing programs overall or for underrepresented groups. Nor did access to additional loan aid result in significant increase in constrained students’ persistence or degree receipt. We document that among programs in which a larger share of graduate students had exhausted their annual federal loan eligibility before the policy change—and thus were more exposed to the expansion in access to credit—federal borrowing and prices increased.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Sandra E. Black, Lesley J. Turner, and Jeffrey T. Denning. Via Brett.

Wheeling and Dealing: How Auto Dealers Put The Brakes on Direct Sales

Alexander Sammon attends the the annual convention of the National Automobile Dealers Association:

Now car dealers are one of the most important secular forces in American conservatism, having taken a huge swath of the political system hostage. They spent a record $7 million on federal lobbying in 2022, far more than the National Rifle Association, and $25 million in 2020 just on federal elections, mostly to Republicans. The NADA PAC kicked in another $5 million. That’s a small percentage of the operation: Dealers mainline money to state- and local-level GOPs as well. They often play an outsize role in communities, buying up local ad space, sponsoring local sports teams, and strengthening a social network that can be very useful to political campaigns. “There’s a dealer in every district, which is why their power is so diffuse. They’re not concentrated in any one place; they’re spread out everywhere, all over the country,” Crane said. Although dealers are maligned as parasites, their relationship to the GOP is pure symbiosis: Republicans need their money and networks, and dealers need politicians to protect them from repealing the laws that keep the money coming in.

The political power of dealers is why many states still prohibit car manufacturers from selling direct to the public, an absurd restriction that I have been complaining about for years. Some progress has been made but also plenty of pushback:

After years of litigation, Michigan, the birthplace of the dealership, recently agreed to let Tesla sell and service cars in-state. Half of states have loosened dealer protections more (red states, ostensibly “pro-business,” tend to have the most binding restrictions), but dealers are still making record profits. Even Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, despite launching his presidential bid with Tesla’s Elon Musk, has raised millions from dealers and given no indication he’d veto two restrictive, dealer-sponsored bills passing through the Florida Legislature. (These bills would make it illegal for car manufacturers to set transparent prices and allow buyers to order EVs from legacy manufacturers online.)

Even “pro-business” Texas, which Elon Musk now calls home, and where Tesla and SpaceX are major employers still doesn’t allow Tesla to sell its cars direct to consumers. As a result:

Teslas made in Texas have to be shipped out of the state and then reimported across state lines to any buyers in Texas who purchase them online, one of many ridiculous workarounds born of dealer-protection laws.

Absurd.

Hat tip: Market Power.

Are We Running Out of Exhaustible Resources?

No, or so says a new paper by Felix Pretis, Cameron Hepburn, Alex Pfeiffer, and Alexander Teytelboym:

Mineral and material commodities are essential inputs to economic production, but there have been periodical concerns about mineral scarcity. However, there has been no systematic recent study that has determined whether mineral commodities have become scarcer over the longer run. Here we provide systematic evidence that worldwide, near-term exhaustion of economically valuable commodities is unlikely. We construct and analyse a new database of 48 economically-relevant commodities from 1957–2015, including estimates of worldwide production, reserves and reserve bases, prices, and production, using publicly-available data and further data requested from the United States Geological Survey. We explore trends in prices, reserves-to-production ratios, and production itself, on a commodity-by-commodity basis, using econometric techniques allowing for structural changes, and further estimate overall trends robust to outlying observations. For almost all commodities, we cannot reject the null hypothesis of no trend in prices and exhaustion, while production has increased. Price signals appear to have guided consumption and provided incentives for innovation and substitution. Concerns about mineral depletion therefore appear to be less important than concerns about externalities, such as pollution and conflict, and ecosystem services (e.g. climate stability) where price signals are often absent.

Julian Simon lives…

Via Jason Crawford.

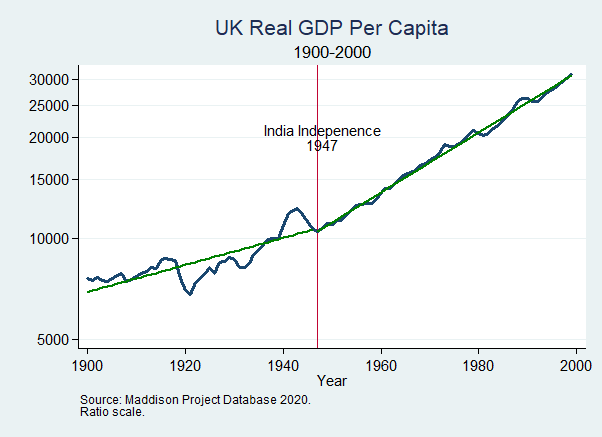

Orwell’s Falsified Prediction on Empire

In The Road to Wigan Pier, George Orwell argued:

…the high standard of life we enjoy in England depends upon our keeping a tight hold on the Empire, particularly the tropical portions of it such as India and Africa. Under the capitalist system, in order that England may live in comparative comfort, a hundred million Indians must live on the verge of starvation–an evil state of affairs, but you acquiesce in it every time you step into a taxi or eat a plate of strawberries and cream. The alternative is to throw the Empire overboard and reduce England to a cold and unimportant little island where we should all have to work very hard and live mainly on herrings and potatoes.

Wigan Pier was published in 1937 and a scant ten years later, India gained its independence. Thus, we have a clear prediction. Was England reduced to living mainly on herrings and potatoes after Indian Independence? No. In fact, not only did the UK continue to get rich after the end of empire, the growth rate of GDP increased.

Orwell’s failed prediction stemmed from two reasons. First, he was imbued with zero-sum thinking. It should have been obvious that India was not necessary to the high standard of living enjoyed in England because most of that high standard of living came from increases in the productivity of labor brought about by capitalism and the industrial revolution and most of that was independent of empire (Most. Maybe all. Maybe more than all. Maybe not all. One can debate the finer details on financing but of that debate I have little interest.) The second, related reason was that Orwell had a deep suspicion and distaste for technology, a theme I will take up in a later post.

Orwell, who was born in India and learned something about despotism as a police officer in Burma, opposed empire. Thus, his argument that we had to be poor to be just was a tragic dilemma, one of many that made him pessimistic about the future of humanity.

*The Corporation and the Twentieth Century*

The author is Richard N. Langlois, and the subtitle is The History of American Business Enterprise. 551 pp. of text. I’ve taught Ph.D Industrial Organization for a good while now, and have always wanted a text that provides an overview and introduction to U.S. business history, with sophistication and good economics, and without being out of date. This is that book, so I am happy indeed.

Acemoglu on the Turkish polity and economy

Preliminary but fairly clear results from the runoff of the Turkish elections show that President Erdogan will have a historic third term. This has implications for democracy and the economy.

— Daron Acemoglu (@DAcemogluMIT) May 28, 2023

Identify a Market Failure and Win Prizes!

The University of Chicago’s Market Shaping Accelerator, led by Rachel Glennerster, Michael Kremer, and Chris Snyder (Dartmouth), is offering up to two million dollars in prizes for new pull mechanisms and applications.

Our inaugural MSA Innovation Challenge 2023 will award up to $2,000,000 in total prizes for ideas that identify areas where a pull mechanism would help spur innovation in biosecurity, pandemic preparedness, and climate change, and for teams to design that incentive mechanism from ideation to contract signing.

Participating teams will have access to the world’s leading experts in market shaping and technical support from domain specialists to compete for their part of up to $2 million prize during multiple phases. Top ideas will also gain the MSA’s support in fundraising for the multi-millions or billions of dollars needed to back their pull mechanism.

…Pull mechanisms are policy tools that create incentives for private sector entities to invest in research and development (R&D) and bring solutions to market. Whereas “push” funding pays for inputs (e.g. research grants), “pull” funding pays for outputs and outcomes (i.e. prizes and milestone contracts). These mechanisms “pull” innovation by creating a demand for a specific product or service, which drives private sector investment and efforts towards developing and delivering that product or technological solution.

One example of a pull mechanism is an Advance Market Commitment (AMC), which is a type of contract where a buyer, such as a government or philanthropic organization, commits to purchasing (or subsidizing) a product or service at a certain price and quantity once it becomes available. This commitment creates a market for the product or service, providing a financial incentive for innovators to invest in R&D and develop solutions to meet that demand.

The first round of prizes are $4,000 for an idea!

The submission template asks applicants to identify a market failure where the social value exceeds private incentives and where we know the measurable outcome we want to encourage (e.g. the development of a vaccine, capturing carbon out of the air, etc.). Submissions are accepted from individuals 18 years and older and organizations around the globe whose participation and receipt of funding will not violate applicable law.

See here for more.

Do tax increases tame inflation?

Here is a new AER article by James Cloyne, Joseba Martinez, Haroon Mumtax, and Paolo Surico. After an extensive data analysis, they arrive at this conclusion:

Based on US federal tax changes post–World War II, our answer is “yes” if personal income taxes are increased but “no” if corporate income taxes are increased.

Of course this is consistent with the view — no longer so commonly admitted — that higher corporate tax rates do have negative supply side effects. There is an ungated version of the paper here.

Selective reporting of placebo tests in top economics journals

Placebo tests, where a null result is used to support the validity of the research design, is common in economics. Such tests provide an incentive to underreport statistically significant tests, a form of reversed p-hacking. Based on a pre-registered analysis plan, we test for such underreporting in all papers meeting our inclusion criteria (n=377) published in 11 top economics journals between 2009-2021. If the null hypothesis is true in all tests, 2.5% of them should be statistically significant at the 5% level with an effect in the same direction as the main test (and 5% in total). The actual fraction of statistically significant placebo tests with an effect in the same direction is 1.29% (95% CI [0.83, 1.63]), and the overall fraction of statistically significant placebo tests is 3.10% (95% CI [2.2, 4.0]). Our results provide strong evidence of selective underreporting of statistically significant placebo tests in top economics journals.

That is from a new paper by Anna Dreber, Magnus Johannesson, and Yifan Yang.

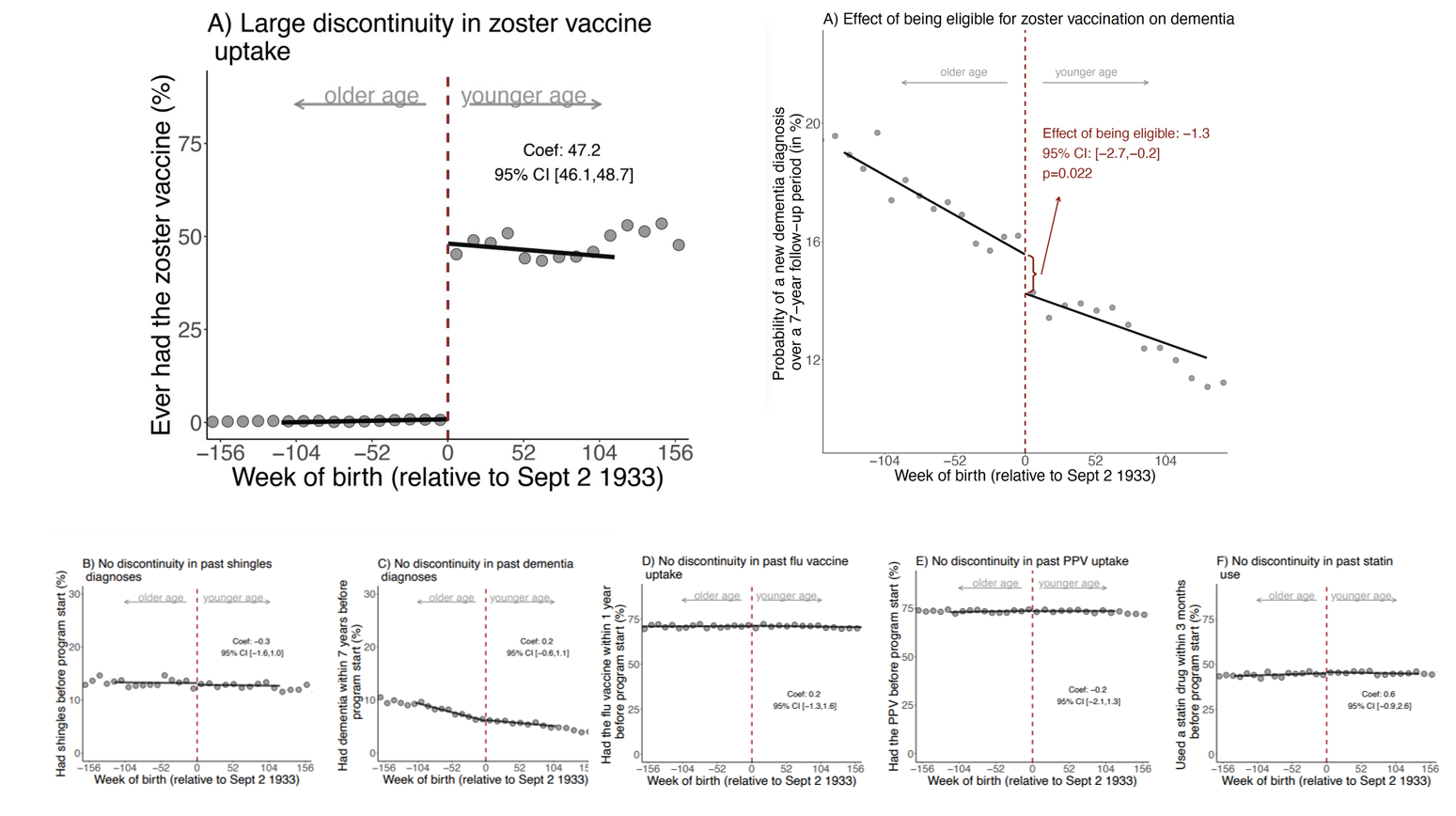

Can the Shingles Vaccine Prevent Dementia?

A new paper provides good evidence that the shingles vaccine can prevent dementia, which strongly suggests that some forms of dementia are caused by the varicella zoster virus (VZV), the virus that on initial infection causes chickenpox. The data come from Wales where the herpes zoster vaccine (Zostavax) first became available on September 1 2013 and was rolled out by age. At that time, however, it was decided that the vaccine would only be available to people born on or after September 2 1933. In other words, the vaccine was not made available to 80 year olds but it was made available to 79 year and 364-day olds. (I gather the reasoning was that the benefits of the vaccine decline with age and an arbitrary cut point was chosen.)

The cutoff date for vaccine eligibility means that people born within a week of one another have very different vaccine uptakes. Indeed, the authors show that only 0.01% of patients who were just one week too old to be eligible were vaccinated compared to 47.2% among those who were just one week younger. The two groups of otherwise similar individuals who were born around September 2 1933 are then tracked for up to seven years, 2013-2020. The individuals who were just “young” enough to be vaccinated are less likely to get shingles compared to the individuals who were slightly too old to be vaccinated (as one would expect if the vaccine is doing it’s job). But, the authors also show that the individuals who were just young enough to be vaccinated are less likely to get dementia compared to the individuals who were slightly too old to be vaccinated, especially among women. A number of robustness tests finds no other sharp discontinuities in treatments or outcomes around the Sept 2, 1933 cut point.

The following graph summarizes. The top left panel shows that the cutoff led to big differences in vaccine uptake, the top right panel shows that there was a smaller but sharp decline in dementia in the vaccinated group. The bottom panel shows that was no discontinuity in a variety of other factors.

Read the whole thing.

I have had my shingles vaccine. As I have said before, vaccination is the gift of a superpower.

Are we evolving toward narrow banking?

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

…the narrow banking model has long been plagued by two major problems. First, there have never been enough safe assets to satisfy the demands of depositors. Second, excessive investment in government securities tends to crowd out private investment. The rise of narrow banking can in part be explained by the mitigation of both these issues.

Alas government debt has gone up! But those new safe assets do have some advantages. And:

The shifting of private funds into Treasury bills could be problematic if that meant credit to the private sector was shrinking. But the rise of private equity and other forms of non-bank finance has made that less of a concern. While private equity growth has slowed since the second half of 2022, it has been on a steady rise since the financial crisis.

Private equity allows many new ventures to be financed, and a run on private equity firms is difficult to pull off, since they are not funding themselves by issuing liquid demand deposits. A private equity venture has a much greater ability to withstand swings in the market. By one metric, private equity measures at almost $12 trillion in value as of mid-2022 — another sign of the US economy advancing in its tools of financial intermediation.

These are not pure market developments, as they are partly a response to the growing regulatory burden on banks, most of all capital requirements. Again, the current regulatory dynamic is not entirely stable. Unstable banks do create trouble, and in return higher legal and regulatory burdens are placed on them, thereby diminishing their profitability. The cycle continues, and implementing tougher regulations hastens the changes rather than halting them.