Category: Education

The culture that is (was) Germany

There are still some students on university campuses who reminisce about the old days. One of those so-called “eternal students” can be found at Christian Albrecht University in the northern city of Kiel. He registered as a student in medicine when Konrad Adenauer was still chancellor and the Berlin Wall hadn’t even been planned yet. Even though he is in his 108th semester, the university does not have the power to throw him out. As one university spokesman explains, the rules for majors that require students to take a state examination, such as medicine, do not contain provisions for ejecting long-term students.

Yet those days are coming to an end, here is much more.

*Grad School Rulz*

Let’s turn the mike over to Bryan Caplan:

Fabio Rojas’ pearls of wisdom for grad students are now available as a concise, information-packed $2 e-book. Definitely worth the money if you have any noticeable interest in grad school.

I have yet to read this book, but Alex and I both love Fabio, who has been a frequent MR guest-blogger in the past. He also has excellent taste in jazz.

From yesterday’s New York Times

They are experimenting with different models of human behavior, here is from Modern Love:

At first his behavior was endearing. He constantly gave me attention, lavishing me with compliments, calls and sometimes gifts. But one morning when I slid out of bed from next to him, things felt different. All his wooing suddenly repelled me.

I crawled back in and tried my best to pretend things were O.K. He showered and dressed. I clenched my teeth when it was time to kiss goodbye, then shut the door behind him, sighed and wondered if he had any idea.

We learn from this same column that butterflies can see with their genitals. And from the NYT Sunday Magazine, here is a Death Row love story:

“I knew you were going to say your favorite color is blue,” he wrote. “It belongs to you. My favorite colors are black and crimson. I love deep, dark red things made of red velvet.”

Overeducation in the UK

Chevalier and Lindley have a new paper:

During the early Nineties the proportion of UK graduates doubled over a very short period of time. This paper investigates the effect of the expansion on early labour market attainment, focusing on over-education. We define over-education by combining occupation codes and a self-reported measure for the appropriateness of the match between qualification and the job. We therefore define three groups of graduates: matched, apparently over-educated and genuinely over-educated; to compare pre- and post-expansion cohorts of graduates. We find the proportion of over-educated graduates has doubled, even though over-education wage penalties have remained stable. This suggests that the labour market accommodated most of the large expansion of university graduates. Apparently over-educated graduates are mostly indistinguishable from matched graduates, while genuinely over-educated graduates principally lack non-academic skills such as management and leadership. Additionally, genuine over-education increases unemployment by three months but has no impact of the number of jobs held. Individual unobserved heterogeneity differs between the three groups of graduates but controlling for it, does not alter these conclusions.

For the pointer I thank Alan Mattich, a loyal MR reader.

A simple approach to macroeconomic theorizing

I can’t say it is guaranteed to work, but I give it a high “p”:

1. Take the macroeconomic theory you hold and stick it into a box.

2. Take the major competing macroeconomic theory, the one you dislike, but taking care that you have selected an approach endorsed by high-IQ researchers. If you dislike them too, that does not disqualify the theory, quite the contrary.

3. Stick theory #2 into the same box.

4. Average the two theories.

5. Pull the average out of the box, and call it your new theory.

How many times should you apply this method? At least once I say.

I am indebted to Hal Varian for a useful conversation on related topics.

North Korean photos

Sorry for the bad link from yesterday, find them here. I thank Yana for the pointer.

The rise of the generalist

I don’t know if I’ve heard anyone say this and I am not quite sure what I think about it myself, but one way to view the economy in the Information Age is that the returns to specialization are falling.

So, those who like such things can go all the way back to Adam Smiths pin factory and think about all the tasks involved in making pins and how each person could become more suited to that task and learn the ins and outs of it.

However, in the information age I can in many cases write a program to repeatedly perform each of these tasks and record ever single step that it makes for later review by me. The individualized skill and knowledge is not so important because it can all be dumped into a database.

What really matters is someone who gets pins. Not the various steps involved in making pins but the concept of the whole pin. What makes a good pin a good pin. How do pins fit into the entire global market. What the next big thing in pins.

This individual will be able to outline a pin vision that she or just a few programmers can easily implement. One could say this is the story of Facebook or Twitter. Really good ideas and just a few people needed to implement them.

However, as IT progress and machines can do more things it could be the story of the economy generally.

In contrast to The Great Stagnation, I would call this The Rise of Generalist or perhaps to be consistent The Great Generalization.

Even if you stop and think for a minute about all of the things that your computer or now even your phone can do, are you now wielding the most generalized tool ever conceived?

I would add in turn that the Generalist boosts the reach of the Specialist, as the Generalist relies on many specialists to supply inputs for his or her outputs. It may be the “tweeners” in the middle who lose income and influence, and that the extreme generalists and specialists will prosper, intellectually and otherwise.

The world’s funniest analogies

From this longer list (funny throughout), presented by Bill Gross and (possibly) derived from student writings, Jason Kottke provides his favorites:

Her vocabulary was as bad as, like, whatever.

From the attic came an unearthly howl. The whole scene had an eerie, surreal quality, like when you’re on vacation in another city and Jeopardy comes on at 7:00 p.m. instead of 7:30.

He was as tall as a six-foot, three-inch tree.

John and Mary had never met. They were like two hummingbirds who had also never met.

His comment:

That first one…I can’t decide if it’s bad or the best analogy ever.

I liked this one:

He was as lame as a duck. Not the metaphorical lame duck, either, but a

real duck that was actually lame, maybe from stepping on a land mine or

something.

From the comments, on local employment of teachers

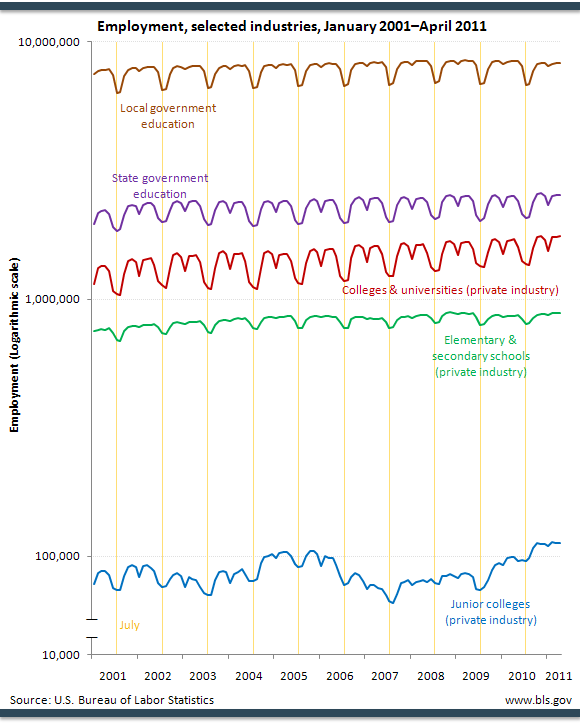

The scaling in the chart makes a big difference. Here’s the data behind the chart, which can by found by following a link on the site that Tyler links to: http://1.usa.gov/oOQXeO. For the local government column only and April figures. (May would be better but the series runs out at April 2011.) April 2011 was at 8.3 million, about 160K less than the peak two Aprils earlier. That’s about 1.5% difference.

That is from RZO, the link and context is here. In the same comment thread, Frank Howland notes that:

K-12 enrollments fell by 0.85% from 2007 to 2009

That’s not exactly the same years and the data go only to 2009 but could it be a general trend across 2009-2011? Given that context, there is still some decline in per capita local teacher employment. Note this is a sector where there is a growing realization that quite a few of the workers should, for non-cyclical reasons, be fired anyway.

Addendum: Karl Smith has a useful graph with seasonal adjustment, coming up with somewhat different numbers.

How many unemployed teachers are there?

This bit from Bruce Yandle challenges the conventional wisdom:

As to hiring teachers, total employment in local government education is already up by one million workers since August 2010. Teacher employment in state government nationwide is up 300,000 workers. The unemployment rate in education and health services at 6.3% is one of the nation’s lowest unemployment rates. While the president implied that teachers were being cut from payrolls at a heavy pace, the data say otherwise. The president’s efforts are seen as misguided if the goal is to ease some of the pain in high unemployment sectors.

Here is another source:

As Figure 1 shows, state government education employment is up by 2.1 percent since the start of the recession while all other state government employment is down 1.9 percent — a substantially larger decline than in other parts of the state-local sector. State government non-education employment began falling less than a year into the recession, and fell below its pre-recession level about a year and a half after the start of the recession.

Do you wish to see more, including on local government education employment?

This BLS graph (look under “And which industries show declining employment over the summer?”) shows a strong seasonal trend which may confound some month-specific citations, but still the number seems to be back to where it had been in earlier years (admittedly the scaling and visuals are not what I would wish for) and more importantly it is hard to spot much effect of the recession at all:

So what exactly is the case here for stimulus of this sector? Is this really a sector to target? I would gladly see and consider alternate numbers and interpretations, but so far I file this under: “Yet another example of something the press should have reported about a President’s speech but didn’t.” Once again, it is the disaggregated demand which matters.

Turnitin: Arming both sides in the Plagiarism War

The internet has made plagiarism much easier and by most accounts plagiarism is increasing rapidly. As a result, over a million instructors now use services like Turnitin, a plagiarism detector that compares submitted manuscripts against a large database of material, including previously submitted manuscripts. What is less well appreciated is that Turnitin also sells its services to students. In fact, students whose professors use Turnitin are encouraged to pre-submit their work to Writecheck which will analyze and “verify” for the students that their paper has “properly quoted, summarized or paraphrased” previous work and it will also relieve students from “worrying that their paper will be recycled without their knowledge.” Uh huh.

In other words, WriteCheck will tell students if their essays will pass Turnitin! David Harrington summarizes nicely:

Turnitin is playing both sides of the fence, helping instructors identify plagiarists while helping plagiarists avoid detection. It is akin to selling security systems to stores while allowing shoplifters to test whether putting tagged goods into bags lined with aluminum thwart the detectors.

New working paper on the impact of economics blogs

This is from the blog Development Impact, but with much more added, the paper can be found here.

Robin Hanson is forming a forecasting team, Kling and Schulz have a new edition

In response to the Philip Tetlock forecasting challenge, Robin is responding:

Today I can announce that GMU hosts one of the five teams, please join us! Active participants will earn $50 a month, for about two hours of forecasting work. You can sign up here, and start forecasting as soon as you are accepted.

There is more detail at the link. Let’s see if he turns away the zero marginal product workers.

There is also a new paperback edition out of the excellent Arnold Kling and Nick Schulz book out, now entitled Invisible Wealth: The Hidden Story of How Markets Work. The book has new forecasts…

Ouch!, yet sometimes markets work

For-profit colleges are facing a tough test: getting new students to enroll.

New-student enrollments have plunged—in some cases by more than 45%—in recent months, reflecting two factors: Companies have pulled back on aggressive recruiting practices amid criticism over their high student-loan default rates. And many would-be students are questioning the potential pay-off for degrees that can cost considerably more than what’s available at local community colleges.

There is more detail here. The graphic on the paper version of the article (not on-line) shows that new University of Phoenix enrollment is down over 40 percent from last year, 47 percent from Kaplan.

Shanghai ranking of world universities in the social sciences

I can’t vouch for the method, but the top ten are quite plausible: Harvard, Chicago, MIT, Berkeley, Columbia, Stanford, Princeton, Yale, U. Penn, and NYU. The top twenty and thirty are plausible too. GMU, by the way, turns up at #41. Economics/Business rankings are here, with a nearly similar top ten.

For the pointer I thank Dan Houser.