Category: Education

What happened to Alywn Young’s Hong Kong vs. Singapore contrast?

From 1992, the paper is here (note by the way an interesting written comment from Paul Krugman at the end). The basic story was that Hong Kong and Singapore had obtained their prosperity by two different paths. Hong Kong had made real productivity gains, but Singapore grew just by throwing more factors of production at the problem of economic growth, including a massive dose of savings and investment, including foreign investment. The share of investment in Singapore’s gdp rose from 9% in 1960 to 43% in 1984, while Hong Kong’s remained roughly steady at about 20%. If you back this out from national income statistics, you can measure that Singapore had very low levels of total factor productivity growth.

But should we believe that story, which by now is twenty years old? After all, these days, Singapore is extremely interested in cutting-edge science and on the frontier in the biosciences and with satellite launches, among other areas. Hong Kong has done fine, but as a finance center and entrepot for the China trade. Not many people look to them as ideas leaders. Maybe both countries somehow turned on the proverbial dime, but I don’t believe the initial Young result for a few reasons:

1. Ever since Michael Mandel, I am skeptical about backing out productivity claims from “value-added” data for extremely open economies. The quality of the data do not support extremely strong claims, and Krugman stresses this point in his comment. By the way, in the Singapore data TFP growth is negative in some sub-periods; see pp.24-5, can you believe -8% for 1970-1990? I take this as indicative of problems in the data and I am not persuaded by Young’s suggestion that it results from cyclical factors.

2. There is much talk about Singapore bringing in so much capital, and they did. But getting all that capital is not as simple as throwing a switch. Presumably the capital — especially the foreign capital — comes in part because investors expect a favorable productivity environment, if only prospectively.

3. Sometimes capital can “carry” or “contain” TFP growth; imagine spending money on a new industrial robot.

4. Some of the measured “TFP growth” may in fact reflect underpriced labor, including underpriced labor migrating from the PRC into Hong Kong. Those workers turned out to be more productive than people were expecting, which creates an apparent TFP residual, and migration of this nature played a larger role in the Hong Kong economy than in Singapore.

5. Young’s measures make him sound skeptical about the future (post-1992) course of economic growth in Singapore, and this has hardly been borne out by the facts. I wouldn’t call this an explicit or formal prediction of his theory but read the paper and the pessimism seeps through, albeit subtly. Is this passage (p.32) prescient or a sign of a mistaken assessment?:

Although I have presented evidence earlier, on the remarkable rate of structural transformation of the Singaporean economy, I feel that the words of Goh Keng Swee, Singapore’s Minister of Finance, in March 1970 are equally compelling: “. .. the electronics components we make in Singapore require less skill than that required by barbers or cooks, involving mostly repetitive manual operations.” By 1983 Singapore was the world’s largest exporter of disk drives. By the late 1980s, Singapore was one of Asia’s leading financial centers. As of today, the Singaporean government is targeting biotechnology and, no doubt, with its deep pockets, will achieve “success” in this sector. One cannot help but sense that this is industrial targeting taken to excess.

To flesh out this history, note two further points:

1. Young is long renowned for the care and quality of his empirical work. He is the sort of researcher who might obsess for six months over a footnote. That is one reason why he has not produced a greater number of papers.

2. This line of research (there are other papers here) was immediately hailed as successful upon its appearance. I read it too at the time and simply assumed it was likely to be true. Even Krugman, despite his insightful worries in his comment, ended up endorsing the Singapore result as true (that link is also an excellent essay for background on this entire set of ideas and debates).

The funny thing is, Young’s hypothesis still could be true. It hasn’t been refuted.

But if you ask me — I don’t believe it, not any more. I take this to be a cautionary tale of how difficult it can be to establish firm knowledge through economics.

What is the causal link between parental income and education?

…the connection between income and student performance “is no less true in the Age of Obama than it was in the Age of Pericles.” But, he points out, most of the connection is not causal, but due to other factors. He cites a study by Julia Isaacs and Katherine Magnuson (Brookings Institution, 2011), that examines an array of family characteristics – such as race, mother’s and father’s education, single parent or two-parent family, smoking during pregnancy – on school readiness and achievement. The Brookings study finds that the distinctive impact of family income is just 6.4 percent of a standard deviation, generally regarded as a small effect. In addition, Peterson calls attention to earlier research by Susan Mayer, former dean of the Harris School at the University of Chicago, which also found that the direct relationship between family income and education success for children varied between negligible and small.

Responding to Ladd’s claim that the gap in reading achievement between students from families in the lowest and highest income deciles is larger for those born in 2001 than for those born in earlier decades, Peterson points out that the achievement gap between income groups was growing at exactly the same time the federal government was rapidly expanding services to the poor – Medicaid, food stamps, Head Start, housing subsidies, and many other programs.

“A better case can be made that any increase in the achievement gap between high- and low-income groups is more the result of changing family structure than of inadequate medical services or preschool education,” Peterson says. In 1969, 85 percent of children under the age of 18 were living with two married parents; by 2010, that percentage had declined to 65 percent. The median income level of a single-parent family is just over $27,000 (using 1992 dollars), compared to more than $61,000 for a two-parent family; and the risk of dropping out of high school increases from 11 percent to 28 percent if a white student comes from a single-parent family instead of a two-parent family. For blacks, the increment is from 17 percent to 30 percent, and for Hispanics, the risk rises from 25 percent to 49 percent.

That is from Harvard’s Kennedy School, from Paul Peterson. Here is more, and for the pointer I thank Ilya Novak.

*Being Global*

The authors are Angel Cabrera and Gregory Unruh, and the subtitle is How to Think, Act, and Lead in a Transformed World. Cabrera is the incoming president of GMU, as of this summer, so of course I am keen to read this book, which arrived in my pile today.

You can follow Cabrera on Twitter here, among other topics he covers leadership, globalization, and also the Spanish economy.

Is Creativity more like IQ or Expertise?

IQ, whatever its flaws, appears to be a general factor, that is, if you do well on one kind of IQ test you will tend to do well on another, quite different, kind of IQ test. IQ also correlates well with many and varied real world outcomes. But what about creativity? Is creativity general like IQ? Or is creativity more like expertise; a person can be an expert in one field, for example, but not in another.

In a short piece in The Creativity Post, cognitive Psychologist Rober Baer argues that creativity is domain-specific:

Efforts to assess creativity have been plagued by supposedly domain-general divergent-thinking tests like the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking, although even Torrance knew they were measuring domain-specific skills. (He create two different versions of the test, one that used verbal tasks and another that used visual tasks. He found that scores on the two tests were unrelated —they had a correlation of just .06—so they could not be measuring a single skill or set of skills. They were—and still are—measuring two entirely different things.) Because these tests have been used in so many psychological studies of creativity, much of what we think we know about creativity may be based on invalid data. These tests have also been widely used in selection for gifted/talented programs — programs that have, in turn, often suffered because by assuming creativity was domain general, these programs often wasted students’ time with supposedly content-free divergent thinking exercises (like brainstorming unusual uses for bricks) that really only develop divergent-thinking skill in limited domains.

The metaphor we use for understanding creativity will impact how we train for creativity:

If one’s goal is to enhance creativity in many domains, then creativity-training exercises need to come from a wide variety of domains—just as we must provide a broad general education if we want students to acquire modest levels of expertise in many areas. But if one’s goal is to increase creativity in just one domain, such as one might want to do in a gifted program focusing on one domain (such as a program in dance, poetry, math, etc)., then it would be appropriate for all of the creativity-training exercises to come from the particular domain of special interest.

Baer’s view is controversial. My inclination is to think that creativity does have a significant general aspect because creativity seems so often to involve combining seemingly disparate ideas. My suspicion is that that there is a neurological basis for this in, to put it crudely, right-brain, left-brain communication channels. The fact that creativity can be stimulated by drugs and travel also suggests to me a general aspect. No one ever says, if you want to master calculus take a “trip” but this does work if you are blocked on some types of creative projects.

Nevertheless, Baer’s view is worth thinking about; he gives more detail to his argument in two academic papers here and here.

Master’s in economics at GMU

The Mercatus MA Fellowship is a two year fellowship designed for students and young professionals who want to enter into or advance a career in public policy. Students have gone onto careers in government (both federal agencies and Capitol Hill) and think tanks, and three have been named presidential management fellows.

Jim Yong Kim nominated to head World Bank

Of course he is likely to get the nod. He is currently president of Dartmouth, and Wikipedia tells us this about his public health background:

Over the past few years, Kim has been involved in the development of a new field focused on improving the implementation and delivery of global health interventions. He believes that progress in developing more effective global health programs has been hindered by the paucity of large-scale systematic approaches to improving program design. This new field will rigorously gather, analyze, and widely disseminate a comprehensive body of practical, actionable insights on effective global health delivery. In order to develop this field, Kim co-founded the Global Health Delivery Project, a joint initiative of Harvard Medical School’s Department of Social Medicine and the Harvard Business School’s Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness. The global health field case studies produced by this project form the core of a new global health delivery curriculum now taught at Harvard School of Public Health. Kim’s team has also developed a web-based “community of practice”, GHDonline.org, to allow practitioners around the world to easily access information, share expertise, and engage in real-time problem solving. Kim is on the Advisory Board of Incentives for Global Health, the NGO formed to develop the Health Impact Fund proposal.

And:

Kim has 20 years of experience in improving health in developing countries. He is a founding trustee and the former executive director of Partners In Health, a not-for-profit organization that supports a range of health programs in poor communities in Haiti, Peru, Russia, Rwanda, Lesotho, Malawi and the United States.

From 2004 to 2006, Kim served as Director of the World Health Organization’s HIV/AIDS department, a post he was appointed to in March 2004 after serving as advisor to the WHO Director General. Kim oversaw all of the WHO’s work related to HIV/AIDS, focusing on initiatives to help developing countries scale up their treatment, prevention, and care programs, including the “3×5” initiative designed to put three million people in developing countries on AIDS treatment by the end of 2005.

He was born in Korea but is an American citizen. He is an expert on tuberculosis. Here is a video of Kim as a rapping spaceman. Here is one good Twitter comment.

International PPP for faculty salaries

Not exactly what I would have thought:

Canada comes out on top for those newly entering the academic profession, average salaries among all professors and those at the senior levels. In terms of average faculty salaries based on purchasing power, the United States ranks fifth, behind not only its northern neighbor, but also Italy, South Africa and India.

Selgin reviews Bernanke on the Gold Standard

George Selgin reviews Bernanke’s course at GWU. He is not happy:

Bernanke’s discussion of the gold standard is perhaps the low point of a generally poor performance, consisting of little more than the usual catalog of anti-gold clichés: like most critics of the gold standard, Bernanke is evidently so convinced of its rottenness that it has never occurred to him to check whether the standard arguments against it have any merit. Thus he says, referring to an old Friedman essay, that the gold standard wastes resources. He neglects to tell his listeners (1) that for his calculations Friedman assumed 100% gold reserves, instead of the “paper thin” reserves that, according to Bernanke himself, were actually relied upon during the gold standard era; (2) that Friedman subsequently wrote an article on “The Resource Costs of Irredeemable Paper Money” in which he questioned his own, previous assumption that paper money was cheaper than gold; and (3) that the flow of resources to gold mining and processing is mainly a function of gold’s relative price, and that that relative price has been higher since 1971 than it was during the classical gold standard era, thanks mainly to the heightened demand for gold as a hedge against fiat-money-based inflation. Indeed, the real price of gold is higher today than it has ever been except for a brief interval during the 1980s. So, Ben: while you chuckle about how silly it would be to embrace a monetary standard that tends to enrich foreign gold miners, perhaps you should consider how no monetary standard has done so more than the one you yourself have been managing!

Read the whole thing for more.

How to raise your child, or yourself, an atheist

That is a discussion from Justin L. Barrett’s new and interesting Born Believers: The Science of Children’s Religious Belief. He gives more than equal time to how to raise your child to be religious, but we’re already pretty good at that. Here are his atheism tips, noting that I am excerpting and paraphrasing:

1. Have less-than-average fluency in reasoning about minds.

2. Do not have children.

3. Stay safe.

4. Get in the habit of crediting or blaming humans for whatever you can.

5. Learn to like pseudoagents (including abstractions).

6. Take time to reflect.

7. Add to these factors indoctrination of the young against religion.

The key theme of Barrett’s book is HADD — Hypersensitive Agency Detection Device, and how pronounced it is in most human beings.

Lunch with Scott Sumner (and others) at China Star

How is that for self-recommending? Here in a short paragraph is my current take on where Ben Bernanke would differ from Scott. As the shadow banking system was imploding in 2008, due to a downward revaluation of collateral, nominal gdp stabilization would have required that the Fed resort to the medium of currency printing on a very large scale. Scott favors such a move. Bernanke would worry that the collapse of (some) intermediation would mean you get most of the output losses anyway, while the printing of currency would create subsequent problems with management of expectations, relative sectoral shocks (currency is only a partial substitute for credit), and medium-term adjustment once the smoke has cleared, not to mention political relations with Congress and interest groups within the Fed system itself. Therefore Bernanke didn’t want to do it, even though in principle he likes to see nominal gdp stabilized, and has written and said as such.

I am not suggesting that Scott agrees with this perspective.

Price discrimination for higher ed *classes*

Faced with deep funding cuts and strong student demand, Santa Monica College is pursuing a plan to offer a selection of higher-cost classes to students who need them, provoking protests from some who question the fairness of such a two-tiered education system.

Under the plan, approved by the governing board and believed to be the first of its kind in the nation, the two-year college would create a nonprofit foundation to offer such in-demand classes as English and math at a cost of about $200 per unit. Currently, fees are $36 per unit, set by the Legislature for California community college students. That fee will rise to $46 this summer.

The classes would be offered as soon as the upcoming summer and winter sessions; and, if successful, the program could expand to the entire academic year. The mechanics of the program are still being worked out, but generally the higher-cost classes would become available after state-funded classes fill up. The winter session may offer only the higher-cost classes, officials said.

That is some premium for reading and writing! The naive might have thought that would have been guaranteed. The story is here and for the pointer I thank Robert Tagorda.

Sentences to ponder

Richard H. Thaler, a former colleague at Cornell and another contributor to the Economic View column, once remarked about an unsuccessful candidate for a faculty position, “What his résumé lacked was five bad papers.”

The rest is from Bob Frank.

Markets in Everything: US Public Schools

Reuters: Across the United States, public high schools in struggling small towns are putting their empty classroom seats up for sale.

In Sharpsville, Pennsylvania, and Lake Placid, New York, in Lavaca, Arkansas, and Millinocket, Maine, administrators are aggressively recruiting international students.

They’re wooing well-off families in China, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Russia and dozens of other countries, seeking teenagers who speak decent English, have a sense of adventure – and are willing to pay as much as $30,000 for a year in an American public school.

The end goal for foreign students: Admission to a U.S. college.

So far the numbers are small. US high schools do outperform those in many other countries but the quality is modest relative to other developed countries and it’s hard for me to see this as a boom market. Nevertheless, I think I will warn my teenager that an exchange program with South Korea is an option.

Hat tip: Daniel Lippman.

Charles Murray on the role of economic forces

This has been debated by Brooks, Krugman, and around the blogosphere, so let us hear from the man himself:

“OK, let’s try this,” he said. “If you get a rising economy, for example, if Barack Obama could say we are going to bring on seven years of incredibly low unemployment, then he would argue that this would do a lot of good to the working class, wouldn’t he?” I agree. “But we already had that in the 1990s, and yet the dropout from the labour force continued to go up, people on social disability went up. Divorce went up. We have no evidence that a robust economy has much to do with these problems at all.”

I point out that many employers complain of a shortage of skills – a large chunk of America’s workforce is not as well equipped as it used to be relative to the rest of the world. If you don’t have the skills to make a living, how can you feel pride in your situation? “Well, that’s a different problem,” says Murray, looking suddenly uninterested. “If you are arguing that 22-year-old men are saying to their girlfriends, ‘I just need a job and then I’ll behave responsibly …’ Well, that’s just bullshit. If you ask women in working class communities, they will say, ‘Why should I marry these losers? It’s like taking another child into the household.’ ”

That is from his FT interview, I am not sure if it is gated for you. The closing paragraph is this:

I feel mildly guilty at having spoiled Murray’s jovial mood but he quickly bounces back. The bill arrives. I disguise my shock at its size. As we get up to leave, Murray says: “Here is an interesting commentary: I was willing to talk to the Financial Times under the influence of alcohol but I’m not willing to play poker under the influence. What does that say?” Don’t worry, I reply, you won’t lose your shirt. Murray laughs. As we are shaking hands, he adds, “I really enjoyed that. We must do it again some time.” Then he strides off in what looks to me like a straight line.

Sentences to ponder

There are all kinds of detailed facts to extract: like that the average fraction of keys I type that are backspaces has consistently been about 7% (I had no idea it was so high!).

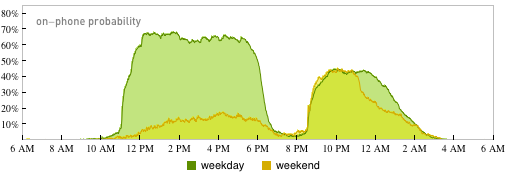

That is from Stephan Wolfram, and it is only the beginning. Here is his on-phone probability:

The entire post is interesting. There are these words too:

And as I think about it all, I suppose my greatest regret is that I did not start collecting more data earlier.

For the pointer I thank Brandon Robison.