Category: Education

Betting markets in everything

A new website is assembling what it calls “the world’s best economics department” in a bid to give prominent academic economists a louder and unfiltered voice in key public-policy debates.

The site, run by the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, plans to pose one question a week and post answers from 40 senior professors at elite U.S. universities. The site went live Sunday, though the panel has been responding to questions for the past few weeks.

Alas, I cannot check the “weblogs” category for this post. The David Wessel article is here, the website itself is here. Let’s bet: pick your metric, how many site visits (or whatever) will they be pulling in six months from now? I bet Scott Sumner beats them with one hand tied behind his back.

Sumner on Yglesias

PS. Congratulations to Matt Yglesias on his new gig. He’s arguably the best progressive economist in the blogosphere, which isn’t bad given that he’s not an economist. I said “arguably” because Krugman’s a more talented macroeconomist. But Yglesias can address a much wider variety of policy issues in a very persuasive fashion. So he’s certainly in the top 5. His blog is the best argument for progressive policy that I’ve ever read. (But not quite persuasive enough to convince me.)

Scott writes more, on the euro.

Sentences to ponder

It is estimated that up to 40 percent of prescriptions go unfilled…

That is from Ezekiel J. Emanuel, here is more. I read somewhere that Zeke has a memoir under contract somewhere, but now Google fails me. Can this be true?

The Bond Market on Education

…Stark Investments is staying away from all student loan bonds right now. It is instead focusing on mortgage-backed debt with comparable yields and less risk…

You know it’s a bad job market when bond investors would rather invest in mortgages than students. As the article in the WSJ notes, investors in student loans have an incentive to be realistic about the value of education and the job market.

Investors like Mr. Ades have a unique view on the future for America’s job-seekers. Their investments depend on accurately predicting young people’s ability to repay their loans, which means they obsess about everything from employment rates by profession to the long-term earning potential of young graduates.

Historically, investors have assumed 25% to 30% of student loans bundled into their bonds will default. But today they are baking in between 30% and 40% default rates among the current crop of graduates…

Not every investment in education is a poor bet:

…This analysis translates into some surprising insights for students and policy makers. For example, in the current economy, it may make more sense to enter a technical college than to go to law school.

…”It’s not just about where you can get the best education,” he said during an interview in the Miami Beach office of his hedge fund, Kawa Capital Management. Students should pick schools where the payoff from higher salaries upon graduation exceeds the cost of the education by the widest margin, he contends, especially when the job market contracts.

By that arithmetic, technical colleges come out on top, Mr. Ades said. “We’re in a skills based economy and what we need is more computer programmers, more [nurses],” he said. “It’s less glamorous but it’s what we need.”

Turning the dialogue from wealth to values

My latest column is about the top one percent, and OWS, here are some paragraphs, including the last three:

The United States has always had a culture with a high regard for those able to rise from poverty to riches. It has had a strong work ethic and entrepreneurial spirit and has attracted ambitious immigrants, many of whom were drawn here by the possibility of acquiring wealth. Furthermore, the best approach for fighting poverty is often precisely not to make fighting poverty the highest priority. Instead, it’s better to stress achievement and the pursuit of excellence, like a hero from an Ayn Rand novel…

But how is that playing out in practice?

For one thing, today’s elites are so wedded to permissive values — in part for their own pleasure and convenience — that a new conservative cultural revolution may have little chance of succeeding. Lax child-rearing and relatively easy divorce may be preferred by some high earners, but would conservatives wish them on society at large, including the poor and new immigrants? Probably not, but that’s often what we are getting.

In the future, complaints about income inequality are likely to grow and conservatives and libertarians won’t have all the answers. Nonetheless, higher income inequality will increase the appeal of traditional mores — of discipline and hard work — because they bolster one’s chances of advancing economically. That means more people and especially more parents will yearn for a tough, pro-discipline and pro-wealth cultural revolution. And so they should.

It remains to be seen how many of us are up to its demands.

It will be very interesting to see, if labor market polarization continues, what kind of disciplinary alternatives will be offered. How about a boot camp, or a neo-Victorian boarding school, to turn your kid into a successful engineer? My admittedly counterintuitive view is that growing income inequality will provide a big boost to cultural conservatism, and perhaps political conservatism too, albeit at levels which are often rhetorical rather than real.

There is much more in the column itself, including a discussion of what Stiglitz, Sachs, Ayn Rand and modern American conservatives get right and wrong. I’m a big fan of the pro-wealth, pro-discipline ethic, although I don’t think that current intellectual discourse is serving up an especially palatable version of it.

I should add that for this column I am grateful for a conversation with John Nye.

Addendum: Mark Thoma comments, as do his commenters, always worth reading.

And the actuaries shall eat

In the debate on unemployment, Ryan Avent makes a common move (related post from Matt here, and Fabio here and Adam here), though I think an incorrect one:

It is remarkable to me how readily old, successful professionals dismiss the labour-market difficulties of young adults as the product of their poorly-chosen majors and general lack of ambition, and on what flimsy evidence they’re prepared to base these views. There are now 3.3m unemployed workers between the ages of 25 and 34. That’s more than twice the level in 2007. There are over 2m unemployed college graduates of all ages; nearly three times the level of 2007. There are many millions more that are underemployed—unwillingly working less than full-time or unwillingly working in a job outside their field which pays less than jobs in their field. As far as I know, the distribution of college majors didn’t swing dramatically from quantitative fields to art history over the past half decade.

The general form of the argument is: “only x changed, therefore x is the cause.” A supply and demand graph, with the shift of one curve, shows that argument to be false. The net effect of the shift will depend, for one thing, on the slope of the other curve, plus whether the other curve has been shifting (more slowly) all along.

A similar kind of argument is applied to the eurozone. Since “things were fine” in year ????, the current crisis can’t be about structural problems in the underlying European model, yet in part it is, for reasons of resiliency and robustness.

Going back to unemployment, labor market opportunities for college grads have been eroding — except for the elite — in absolute terms since 1997-2000, well before the collapse in AD. If those same grads are highly willing to be geographically mobile, highly willing to consider actuarial training, and highly willing to take tougher courses and study where the jobs are (doesn’t have to be tech subjects, some of those are failing too), the unemployment response to a given AD shock will be much lower. But they aren’t, so it isn’t. I’ve seen only small adjustments in the ambition and flexibility of college goers, not enough preaching about TGS I suppose.

In an era where both monetary and fiscal policies have underperformed, looking at both sides of the market is essential.

You can even give this all a Keynesian take (though I would prefer a TGS framework). Since 1997-2000, there is downward pressure on lots of wages, but morale matters and labor market incumbents retain a favored position. Though some wages fall, employers resist that downward pressure, and pass along a lot of the burden of adjustment to new job seekers. Even if that original downward pressure on wages is smallish, new job seekers have to make big adjustments in their career plans, majors, ambitions, etc. to get through the door at all. They didn’t.

That’s the same argument that Keynesians cite and indeed insist upon in other contexts. It is somewhat harder to see when you start with a slower erosion in real wage opportunities, rather than a sudden AD shock, but it doesn’t make sense for Keynesians to dismiss it.

The real issue, I suspect, is that many people are allergic to arguments which appear to “blame” the job seekers, rather than government inaction, but it’s not about blame one way or the other. It’s about the desire to have a fuller and better model, with richer causal chains, and to see through all the variations to a deeper level.

To put it rather immodestly, my arguments are a lot stronger than many people think!

Facts about education

Here is one:

In 2003, the first year the Babson group and Sloan-C conducted the survey, 57 percent of academic leaders estimated that learning outcomes in online courses were equal or superior to those of face-to-face courses. This year, the figure was 67 percent.

From Peter Orszag, writing about budgetary pressures, here is another:

Some admittedly imperfect indicators suggest the quality of public higher education is already fading. For example, in 1987, both UC Berkeley and the University of Michigan were included in U.S. News & World Report’s ranking of the top 10 universities. By this year, there were no public universities in the top 10 — and UC Berkeley, the top-ranked public school, had fallen from fifth to 21st.

Put these two facts together, and what is your prediction?

Who gets what wrong?

My colleague Daniel Klein reports from the front:

…under the right circumstances, conservatives and libertarians were as likely as anyone on the left to give wrong answers to economic questions. The proper inference from our work is not that one group is more enlightened, or less. It’s that “myside bias”—the tendency to judge a statement according to how conveniently it fits with one’s settled position—is pervasive among all of America’s political groups. The bias is seen in the data, and in my actions.

And what do the “right-wing” thinkers get wrong?

More than 30 percent of my libertarian compatriots (and more than 40 percent of conservatives), for instance, disagreed with the statement “A dollar means more to a poor person than it does to a rich person”—c’mon, people!—versus just 4 percent among progressives. Seventy-eight percent of libertarians believed gun-control laws fail to reduce people’s access to guns. Overall, on the nine new items, the respondents on the left did much better than the conservatives and libertarians. Some of the new questions challenge (or falsely reassure) conservative and not libertarian positions, and vice versa. Consistently, the more a statement challenged a group’s position, the worse the group did.

A college education, by the way, doesn’t help much. Here is another statement of the conclusion:

A full tabulation of all 17 questions showed that no group clearly out-stupids the others. They appear about equally stupid when faced with proper challenges to their position.

That’s a lesson David Hume would have appreciated.

Very good sentences

I make no apologies for ignoring these little toy models, and having my policy analysis incorporate a complex mixture of politics, macroeconomic history, well-established basic economic principles, and logic.

Not From The Onion

Here’s an astounding illustration of my argument that “American students are not studying the fields with the greatest economic potential.”

The Nation: A few years ago, Joe Therrien, a graduate of the NYC Teaching Fellows program, was working as a full-time drama teacher at a public elementary school in New York City. Frustrated by huge class sizes, sparse resources and a disorganized bureaucracy, he set off to the University of Connecticut to get an MFA in his passion—puppetry. Three years and $35,000 in student loans later, he emerged with degree in hand, and because puppeteers aren’t exactly in high demand…he’s working at his old school as a full-time “substitute”…[earning less than he did before].

…Like a lot of the young protesters who have flocked to Occupy Wall Street, Joe had thought that hard work and education would bring, if not class mobility, at least a measure of security…But the past decade of stagnant wages for the 99 percent and million-dollar bonuses for the 1 percent has awakened the kids of the middle class to a national nightmare: the dream that coaxed their parents to meet the demands of work, school, mortgage payments and tuition bills is shattered.

What astounds me is not that someone could amass $35,000 in student loans pursuing a dream of puppetry, everyone has their dreams and I do not fault Joe for his. What astounds me is that Richard Kim, the executive editor of The Nation and the author of this article, thinks that the failure of a puppeteer to find a job he loves is a good way to illustrate the “national nightmare” of the job market. Even in a wealthy society it’s a privilege to have the kind of job that Kim thinks are the entitlement of the middle class. And, as Tyler says, we are not as wealthy as we thought we were.

In considering the plight of the puppeteer lets also remember that millions of the unemployed would be grateful to have a job that they don’t like.

By the way, should you be so inclined, Therrien has a Kickstarter project where you can voluntarily donate to create “a nationwide flowering of spectacle puppet theater joyously spreading a new public consciousness!” You may also wish to know that according to Mike Riggs at Reason:

The pro-puppet American Recovery and Reinvestment Act doled out $50,000 to the Center for Puppetry Arts in Atlanta; $25,000 to the Sandglass Center for Puppetry and Theater Research in Vermont; and $25,000 to the Spiral Q Puppet Theater in Philadelphia.

The study of science is hard

The excitement quickly fades as students brush up against the reality of what David E. Goldberg, an emeritus engineering professor, calls “the math-science death march.” Freshmen in college wade through a blizzard of calculus, physics and chemistry in lecture halls with hundreds of other students. And then many wash out.

Studies have found that roughly 40 percent of students planning engineering and science majors end up switching to other subjects or failing to get any degree. That increases to as much as 60 percent when pre-medical students, who typically have the strongest SAT scores and high school science preparation, are included, according to new data from the University of California at Los Angeles. That is twice the combined attrition rate of all other majors.

Could it be that too many people like being the smartest one in the room? Or is it some other explanation?:

“But if you take two students who have the same high school grade-point average and SAT scores, and you put one in a highly selective school like Berkeley and the other in a school with lower average scores like Cal State, that Berkeley student is at least 13 percent less likely than the one at Cal State to finish a STEM degree.”

Here is the story, here is Alex’s earlier post. Science itself is even harder.

Very good sentences

Perhaps the “something nicer” which should replace capitalism is a more nuanced – and more accurate – account of capitalism itself.

That is from John Kay, here is more.

College has been oversold

Here, drawn from my new e-book, Launching the Innovation Renaissance (published by TED) is part of a section on college education. (See also the op-ed in IBD)

Educated people have higher wages and lower unemployment rates than the less educated so why are college students at Occupy Wall Street protests around the country demanding forgiveness for crushing student debt? The sluggish economy is tough on everyone but the students are also learning a hard lesson, going to college is not enough. You also have to study the right subjects. And American students are not studying the fields with the greatest economic potential.

Over the past 25 years the total number of students in college has increased by about 50 percent. But the number of students graduating with degrees in science, technology, engineering and math (the so-called STEM fields) has remained more or less constant. Moreover, many of today’s STEM graduates are foreign born and are taking their knowledge and skills back to their native countries.

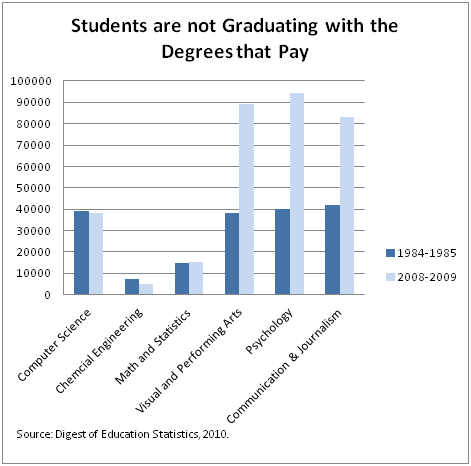

Consider computer technology. In 2009 the U.S. graduated 37,994 students with bachelor’s degrees in computer and information science. This is not bad, but we graduated more students with computer science degrees 25 years ago! The story is the same in other technology fields such as chemical engineering, math and statistics. Few fields have changed as much in recent years as microbiology, but in 2009 we graduated just 2,480 students with bachelor’s degrees in microbiology — about the same number as 25 years ago. Who will solve the problem of antibiotic resistance?

If students aren’t studying science, technology, engineering and math, what are they studying?

In 2009 the U.S. graduated 89,140 students in the visual and performing arts, more than in computer science, math and chemical engineering combined and more than double the number of visual and performing arts graduates in 1985.

The chart at right shows the number of bachelor’s degrees in various fields today and 25 years ago. STEM fields are flat (declining for natives) while the visual and performing arts, psychology, and communication and journalism (!) are way up.

There is nothing wrong with the arts, psychology and journalism, but graduates in these fields have lower wages and are less likely to find work in their fields than graduates in science and math. Moreover, more than half of all humanities graduates end up in jobs that don’t require college degrees and these graduates don’t get a big college bonus.

Most importantly, graduates in the arts, psychology and journalism are less likely to create the kinds of innovations that drive economic growth. Economic growth is not a magic totem to which all else must bow, but it is one of the main reasons we subsidize higher education.

The potential wage gains for college graduates go to the graduates — that’s reason enough for students to pursue a college education. We add subsidies to the mix, however, because we believe that education has positive spillover benefits that flow to society. One of the biggest of these benefits is the increase in innovation that highly educated workers theoretically bring to the economy.

As a result, an argument can be made for subsidizing students in fields with potentially large spillovers, such as microbiology, chemical engineering, nuclear physics and computer science. There is little justification for subsidizing sociology, dance and English majors.

College has been oversold. It has been oversold to students who end up dropping out or graduating with degrees that don’t help them very much in the job market. It also has been oversold to the taxpayers, who foot the bill for these subsidies.

Signaling or human capital?

Is there any way to sustain the current revenue model of higher ed? How about firefighters? You can read this story as illustrating human capital theories of education, signaling theories, or both:

“We still put out fires with water,” said Deason, who is also a lieutenant and paramedic at a fire department in Homewood, Ala. But fire companies these days “need people who are a little more advanced with their education.”

As a result, college degrees that are not fire-related can also help. Deason and Crowther said fire departments increasingly want career employees who have strong critical thinking skills, and who can write grants or do public speaking, particularly as they progress to leadership roles.

Two other drivers of the growing higher education demand among firefighters are the recession and colleges’ online offerings. Purchasing and budget decisions are more important than ever, as most municipalities have tight finances. And financial and technical know-how helps when considering big expenses, like the $675,000 fire engine Deason said his company recently bought.

… In the future, he said advanced degrees will probably be an “absolute requirement” for most chief positions.

Why the current revenue model of higher education is in trouble

The picture for females is also not pleasant, all from the excellent Michael Mandel. Those are simple facts, denied by some.

Non-college grads also have seen declining wages, and so one can look at the “finish college vs. finish high school only” margin and conclude that the return to higher education is robust. Another approach is to look at the “finish college and get on a real career track” vs. “finish college and hang out” margin and conclude the sector is in trouble, which indeed is the case. Don’t get stuck looking at the old margins only, the new and powerful margin, I am sorry to say, is relative to unemployment or extreme underemployment. The status and avoid-shame returns are high enough to keep a lot of people going to college, at current prices, but the falling real wages for graduates aren’t going to sustain an enormous amount of extra sectoral growth, including on the price side. Nor do I expect the preceding orgy of student debt to repeated, at that level, anytime soon.