Category: Education

Stuff they don’t teach in graduate school

Chris Blattman has a problem to do with his research that they just don't teach about in graduate school. Which type of anti-malarial drugs should he provide for his research assistants?

be really fantastic if none of them fell deathly ill because of, well, my

research papers.

Here's the question. We have at least two perfectly

common anti-malarial options–doxycycline and mefloquine–each of which cost a

few cents each. They've been around a while, so we know what to expect. Doxy:

sun sensitivity in the occasional case, and no milk in your coffee that morning

(which is a tragedy). Mefloquine: crazy dreams among a few (including

me).

Along comes a fancy-pants new drug, Malarone. It costs $6 a pill,

with insurance, and has to be taken every day. Why would I pay 120 times more

than the generic? Is it 10 times as effective? 1.2 times? Just as effective? As

far as I can tell, there aren't studies on the matter.

Markets in everything

It's funny but to me this story is more surprising than the usual fare of prediction markets on whether bronzed bones of your ancestors will be transcribed into binary code for your Kindle, or simultaneously used as collateral for CDS swaps and bundled with adultery insurance:

Reached on the phone, Richard A. Hanson isn't quite sure he's ready

to give an interview about this week's sale of Waldorf College. The

college's president has talked quite a bit locally, trying to assure

students, professors and the residents of Forest City, Iowa, that

selling the liberal arts institution to a for-profit, online university

is the best (in fact, only) option.

What persuaded Hanson to

talk about what's happening at Waldorf is the question of whether he

thinks other colleges will soon be facing the same choice. "You are

going to be seeing a lot more of this from colleges like us," he said.

They're actually selling the college. Hurrah.

How our macro book differs

Alex already has suggested some points related to economic growth; I'll add to that:

1. We make macroeconomics as intuitive as microeconomics. Our macro is based on the idea of incentives, consistently applied.

2. We cover the current financial crisis.

3. We show a simple — yes truly simple — way of teaching the Solow Growth model. I call it Really Simple Solow. But if that's not simple enough for you, you can skip it and just call it Long-Run Aggregate Supply.

4. We offer equal and balanced coverage of neo Keynesian and real business cycle models. Most other texts emphasize one or the other.

5. We offer an intuitive way of teaching real business cycle theory. No intertemporal optimization representative agent models. Can you explain to your grandmother why swine flu has been bad for the Mexican economy? If so, you also think that real business cycle theory can be taught simply and intuitively.

6. Our version of the AD-AS model actually makes sense. We don't mash together real and nominal interest rates into the same diagram, we don't treat the Taylor rule as an assumption for deriving an AD curve, and we do the analysis consistently in terms of dynamic rates of change. (On the latter point for instance it is the rate of inflation which influences economic behavior, not the absolute level of prices per se, yet so often "p" rather than "pdot" goes on the vertical axis.)

The AD-AS analysis covers both neo Keynesian and RBC models and can be done with three simple curves in one simple graph. There is only one (consistent) model which needs to be taught for presenting the major macro ideas.

Alex and I vowed we would not stop working on this book until macro ceased to be the "ugly sister" of the micro/macro pair. Modern Principles: Macroeconomics is the result of that Auseinandersetzung.

We are heartened by the response to our previous posts on the book. Again, please do contact us if you are interested in a review copy for teaching purposes. Here is the book's home page.

Modern Principles: Macroeconomics, Economic Growth

course an embarrassment. In much of the developing world, diarrhea

is a killer, especially of children. Every year 1.8 million

children die from diarrhea. Ending the premature deaths of these

children does not require any scientific breakthroughs, nor does it

require new drugs or fancy medical devices. Preventing these deaths requires

only one thing: economic growth.

That’s the opening paragraph of The Wealth of Nations and Economic Growth, Chapter 6 in Modern Principles: Macroeconomics. Does the opening make you a little bit squeamish? We hope so–we wanted an opening that would jar students out of complacency and remind them how vital economic growth is to human life. Â

Due to its importance, we have more material on growth and development than any other principles text.  In Chapter 6 we lay out the key facts and the basic framework for understanding economic growth. I think we do an especially good job explaining that the proximate causes of growth, increases in capital, labor, and technology must themselves be explained. Why do people save? Why do people invest?  Why do people research and develop new ideas?  It’s these questions which connect macroeconomics to microeconomics and point to the fundamental importance of incentives and institutions. These questions also foreshadow future chapters on savings, investment, financial intermediation and the economics of ideas.Â

For a limited time, you can read Chapter 6 at the link above (and do enjoy the pretty color pictures before you print!).  Tyler and I will be writing more about Modern Principles: Macroeconomics this week; you can also find more information at www.SeeTheInvisibleHand.com.

Coming soon

There is a Micro book and a consolidated text as well. Please do contact Alex or me if you are interested in classroom use.

Addendum: Arnold Kling comments.

One economist’s perspective on the law and economics movement

In this piece, from a CrookedTimber symposium, I stress that market-oriented economists are culturally and intellectually quite different from their counterparts in the legal side of academia:

One topic which interests me is how the “conservative” law and economics movement, as it is found in legal academia, differs from “market-oriented” economics, as it is found in the economics profession. The “right wing” economist and legal scholar will agree on many issues but you also will find fundamental variations in their temperament and political stances.

Market-oriented economists tend to be libertarian and it is rare that they have much respect for the U.S. Constitution beyond the pragmatic level. The common view is that while a constitution may be better than the alternatives, it is political incentives which really matter. James M. Buchanan’s program for a “constitutional economics” never quite took off and insofar as it did it has led to the analytic deconstruction of constitutions rather than their glorification. It isn’t hard to find libertarian economists who take “reductionist” views of constitutions and trumpet them loudly.

I also discuss my experiences teaching at GMU Law, why the law and economics movement grew so rapidly, and why the initially conservative nature of that movement is more or less over. Read the whole thing.

Debating Economics

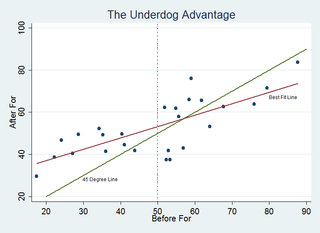

Intelligence Squared has held a series of debates in which they poll ayes and nayes before and after. How should we expect opinion to change with such debates? Let’s assume that the debate teams are evenly matched on average (since any debate resolution can be written in either the affirmative or negative this seems a weak assumption). If so, then we ought to expect a random walk; that is, sometimes the aye team will be stronger and support for their position will grow (aye after – aye before will increase) and sometimes the nay team will be stronger and support for their position will grow. On average, however, we ought to expect that if it’s 30% aye and 70% nay going in then it ought to be 30% aye and 70% nay going out, again, on average. Another way of saying this is that new information, by definition, should not swing your view systematically one way or the other.

Alas, the data refute this position. The graph shown below (click to enlarge) looks at the percentage of ayes and nayes among the decided  before and after. The hypothesis says the data should lie around the 45 degree line. Yet, there is a clear tendency for the minority position to gain adherents – that is, there is an underdog advantage so positions with less than 50% of the ayes before tend to increase in adherents and positions with greater than 50% ayes tend to lose adherents. What could explain this?

before and after. The hypothesis says the data should lie around the 45 degree line. Yet, there is a clear tendency for the minority position to gain adherents – that is, there is an underdog advantage so positions with less than 50% of the ayes before tend to increase in adherents and positions with greater than 50% ayes tend to lose adherents. What could explain this?

I see two plausible possibilities.

1) If the side with the larger numbers has weaker adherents they could be more likely to change their mind.

2) The undecided are key and the undecided are lying.

For case 1, imagine that 10% of each group changes their minds; since 10% of a larger number is more switchers this could generate the data. The problem with 1 and with the data more generally is that we don’t seem to see a tendency towards 50:50 in the world. We focus on disputes, of course, but more often we reach some consensus (the moon is not made of blue cheese, voodoo doesn’t work and so forth).

Thus 2 is my best guess. Note first that the number of “undecided” swing massively in these debates and in every case the number of undecided goes down a lot, itself peculiar if people are rational Bayesians. A big swing in undecided votes is quite odd for two additional reasons. First, when Justice Roberts said he’d never really thought about the constitutionality of abortion people were incredulous. Similarly, could 30% of the audience (in a debate in which Tyler recently participated (pdf)) be truly undecided about whether “it is wrong to pay for sex”? Second, and even more doubtful, could it be that 30% of the people at the debate were undecided–thus had not heard arguments in let’s say the previous 10 years that converted them one way or the other–but on that very night a majority of the undecided were at last pushed into the decided camp? I think not, thus I think lying best explains the data.

Some questions for readers. Can you think of another hypothesis to explain the data? Can you think of a way of testing competing hypotheses? And does anyone know of a larger database of debate decisions with ayes, nayes and undecided before and after?

Hat tip to Robin for suggesting that there might be a tendency to 50:50, Bryan and Tyler for discussion and Robin for collecting the data.

Gerry Gunderson and the battle at Trinity College

In one previously undisclosed fight, Trinity College in Connecticut

is facing government scrutiny for its plan to spend part of a $9

million endowment from Wall Street investing legend Shelby Cullom Davis.

Trinity's Davis professor of business, Gerald Gunderson, says he

believed the plan, which would have funded scholarships for

international students, violated the wishes of the late Mr. Davis. He

alerted the Connecticut attorney general's office. Then, Mr. Gunderson

said in notes submitted to the agency, Trinity's president summoned him

to the school's cavernous Gothic conference room, where he called the

professor a "scoundrel" and threatened not to reappoint him.

Gunderson is a market-oriented economist; here is the full story.

Strange Trip

Yesterday I chaperoned a group of ten year-olds to the Smithsonian. As the bus rolled by, I pointed out the Federal Reserve to my kid and one of the other boys his eyes all aglow said "ooohh, that's where Ben Bernanke works!" Even taking into account the possible uber-nerdiness of the group, this was a surprise.

On another note, five years ago (!) I pointed to a sign at the Smithsonian warning of another ice age and recent global cooling – well the sign (or something like it) is still there only now it does have a little placard above saying that this exhibit will soon be changed to reflect more recent science.

Airlifting Yemeni Jews

Here is a new paper:

This paper estimates the effect of the childhood environment on a large

array of social and economic outcomes lasting almost 60 years, for both

the affected cohorts and for their children. To do this, we exploit a

natural experiment provided by the 1949 Magic Carpet operation, where

over 50,000 Yemenite immigrants were airlifted to Israel. The

Yemenites, who lacked any formal schooling or knowledge of a

western-style culture or bureaucracy, believed that they were being

"redeemed," and put their trust in the Israeli authorities to make

decisions about where they should go and what they should do. As a

result, they were scattered across the country in essentially a random

fashion, and as we show, the environmental conditions faced by

immigrant children were not correlated with other factors that affected

the long-term outcomes of individuals. We construct three summary

measures of the childhood environment: 1) whether the home had running

water, sanitation and electricity; 2) whether the locality of residence

was in an urban environment with a good economic infrastructure; and 3)

whether the locality of residence was a Yemenite enclave. We find that

children who were placed in a good environment (a home with good

sanitary conditions, in a city, and outside of an ethnic enclave) were

more likely to achieve positive long-term outcomes. They were more

likely to obtain higher education, marry at an older age, have fewer

children, work at age 55, be more assimilated into Israeli society, be

less religious, and have more worldly tastes in music and food. These

effects are much more pronounced for women than for men. We find weaker

and somewhat mixed effects on health outcomes, and no effect on

political views. We do find an effect on the next generation – children

who lived in a better environment grew up to have children who achieved

higher educational attainment.

Here is an ungated version.

Markets in everything, or Department of Why Not?

Bouncers, ex-soldiers and former police officers are being brought into schools to provide "crowd control" and cover absent teachers' lessons, a teacher has revealed.

One

school, thought to be in London, employed two permanent cover teachers

through an agency for professional doormen, the National Union of

Teachers annual conference in Cardiff heard today.

Bouncers, who

more usually work nights keeping order in pubs and clubs, are being

employed in schools because they are "stern and loud", said Andrew

Baisley, a teacher at Haverstock school in Camden, north London.

Here is the story.

One hypothesis why CEOs do not have a backward-bending labor supply curve

BECAUSE THE CEOs THINK KIDS ARE BORING.

That's Penelope Trunk, here is much more.

OS

Erika Eiffel and Eija-Riitta Eklöf Berliner-Mauer; not my thing personally but I say "why not?" Compare it to the many people who have no love in their lives at all. Video here.

If you are tempted to snicker, first think long and hard about all the money, time and effort you put into listening to music.

Peter Orszag’s tip for discipline

Orszag has employed this knowledge while training for a marathon.

"If

I didn't achieve what I wanted to, a very large contribution would

automatically come out of my credit card and go to a charity that I

very much didn't support," Orszag says of his training strategy. "So

that was a very strong motivation, as I was running through mile 15 or

16 or whatever it was, to remind myself that I really didn't want to

give the satisfaction to that charity for the contribution."

He declines to name the charity.

The source is here.

Harvey Mansfield on economists

Kent Guida sent me this very interesting article; here are a few bits:

The economists I know are generally, as individuals, sober and

cautious, the most respectable of all professors and in their honesty

and reliability representing the best in bourgeois virtue. But when

they get together as economists, they give way to boyish irrational

exuberance over the accomplishments and prospects of economics as a

science.

…Overconfidence in overcoming chance is the way of life recommended by

economists. It is the way of life known as progress by liberals and as

growth by conservatives, who are secretly united by overconfidence in

their knowledge of the future which they describe diversely and call by

different names.

…Now, the main consequence of living the over-confident life is to

believe that virtue is not necessary. Perhaps this is the main cause as

well as consequence of that life. Virtue is a chancy quality because

you may not have it or live up to it. It seems less reliable than

self-interest with its allies, fear and greed. Everybody has

self-interest, which is not true of virtue. But at least virtue does

not depend on predicting the future. On the contrary, virtue is a

resource for everyone when bad times come–something to fall back on,

to give cheer, to restore. On top of that, virtue will save you from

being corrupted by good fortune as well. This is the great truth taught

by the Stoics.