Category: Film

*Inside Job*

Nick writes to me:

I'm an undergrad math/Econ double major and aspiring economist. I also read your blog (amongst others) daily. You said today that "Inside Job" was "half very good and half terrible." Critical reviews are widespread, but prominent economists haven't said much. I was wondering if you could expound on your terse critique in an email or blog post.

It's been a while since I've seen the movie, but here goes. The best parts are on excess leverage, the political economy of the crisis, and the attitudes of the economics profession. Overall it is remarkable how much economics is in the movie, even though some of it is quite bad. The visuals and pacing are excellent and many scenes deserve kudos.

The worst parts are the misunderstandings of deregulation. Glass-Steagall repeal was not a major factor, much of the sector remained highly regulated, and there is no mention of the failure to oversee the shadow banking system. The entire discussion has more misses than hits. The smirky association of major bankers with expensive NYC prostitutes (on one hand based on very little evidence, on the other hand probably true) was inexcusable. There is talk of "predatory lending," but it is not mentioned that many borrowers committed felonies, or were complicit in felonies ("on the form, put down any income you would like"). Most generally, there is virtually no understanding of the complexity of the dilemmas involving in either public service or in running a major corporation.

Overall, the movie's smug moralizing makes me wonder: is this a condescending posture, spooned out with contempt to an audience regarded, one way or another, as inferior and undeserving of better? Or are the moviemakers actually so juvenile and/or so ignorant of the Western tradition — from Thucydides to Montaigne to Pascal to Shakespeare to Ibsen to FILL IN THE BLANK — that they themselves accept the very same simplistic moral portrait? If so, most of all I feel sorry for how much of life's complexities they are missing and how impoverished their reading and moviegoing and theatregoing must be.

Do you remember the scene in Hamlet, where Hamlet tries to judge the King by enacting a pantomime play in front of him, to see how the King would respond to a work of art? I think of that often.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul

I find it increasingly hard to resist the notion that he is the most enduring director of our time. I've now seen Syndromes and a Century (the best place to start), Blissfully Yours, and Tropical Malady and wish to rewatch them all. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (not yet on DVD) won the Golden Palm at Cannes this year. Themes of his movies include dreams, medicine and its authority relationships, sex and eroticism, homosexuality, the nature of cinema itself, memory, sudden fractures of reality, surrealism, and the modernization of Thailand. [Insert Dancing About Architecture cliche here.] You could frame most of the shots from these movies and turn them into stunning photographs. The plot structure is stronger than it appears at first. These movies also have notable (though quiet) soundscapes, as you would find in a Tarkovsky film.

If you expect to disagree, try then the excellent Ong Bak.

For the original pointer to Apichatpong Weerasethakul, I thank Andrew Hazlett. Here is an MP3 on pronouncing his name properly.

Ideas Behind Their Time

We are all familiar with ideas said to be ahead of their time, Babbage’s analytical engine and da Vinci’s helicopter are classic examples. We are also familiar with ideas “of their time,” ideas that were “in the air” and thus were often simultaneously discovered such as the telephone, calculus, evolution, and color photography. What is less commented on is the third possibility, ideas that could have been discovered much earlier but which were not, ideas behind their time.

Experimental economics was an idea behind its time. Experimental economics could have been invented by Adam Smith, it could have been invented by Ricardo or Marshall or Samuelson but it wasn’t. Experimental economics didn’t takeoff until the 1960s when Vernon Smith picked it up and ran with it (Vernon was not the first experimental economist but he was early).

(Economics, and perhaps social science in general, seems behind its time compared say with political science.)

A lot of the papers in say experimental social psychology published today could have been written a thousand years ago so psychology is behind its time. More generally, random clinical trials are way behind their time. An alternative history in which Aristotle or one of his students extolled the virtue of randomization and testing does not seem impossible and yet it would have changed the world.

Technology can also be behind its time. View morphing (“bullet time”) could have been used much more frequently well before The Matrix in 1999 (you simply need multiple cameras from different angles triggered at the same time and then inserted into a film) but despite some historical precedents the innovation didn’t happen.

Ideas behind their time may be harder to discover than other ideas–“if this is so great why hasn’t it been done before”? is an attack on ideas behind their time that other innovations do not have to meet. Is this why social innovations are often behind their time?

What other ideas were behind their time? Are some types of ideas more likely to be behind their time than others? Why?

Addendum: See Jason Crawford on Why did it take so long to invent X?

Assorted links

1. Taiwanese bride marries herself.

2. Victor Menaldo has a blog; he is the researcher behind the myth of the resource curse and "rainfall and democracy."

4. Who is the most important avant-garde filmmaker? After Warhol, Jonas Mekas, Stan Brekhage, Kenneth Anger, and Maya Deren top the NYT citation list.

Why Has TV Replaced Movies as Elite Entertainment?

Edward Jay Epstein, The Hollywood Economist, has a good post on the economics of movies and television and how this has contributed to a role reversal:

Once upon a time, over a generation ago, The television set was commonly called the “boob tube” and looked down on by elites as a purveyors of mind-numbing entertainment. Movie theaters, on the other hand, were con sidered a venue for, if not art, more sophisticated dramas and comedies. Not any more. The multiplexes are now primarily a venue for comic-book inspired action and fantasy movies, whereas television, especially the pay and cable channels, is increasingly becoming a venue for character-driven adult programs, such as The Wire, Mad Men, and Boardwalk Empire.

Why? Epstein’s explanation is the rise of Pay-TV. You can understand what has happened with some microeconomics. Advertising supported television wants to maximize the number of eyeballs but that often means appealing to the lowest common denominator (this is especially true when there are just three television stations). The programming that maximizes eyeballs does not necessarily maximize consumer surplus.

See the diagram.

Pay-TV changes the economics by encouraging the production of high consumer-surplus television because with Pay-TV there is at least some potential for trading off eyeballs for greater revenue. In addition, as more channels become available, lowest common denominator television is eaten away by targetted skimming. Thus, in one way or another, Pay-TV has come to dominate television.

The movies, however, have become more reliant on large audiences–at least relative to television. Note that even though the movies are not free, a large chunk of the revenue is generated by concessions–thus the movie model is actually closer to a maximizing mouths model than it might first appear (see also my brother’s comments on how flat movie pricing makes it difficult for indie films to compete). Finally, the rise of international audiences for movies has fed a lowest common denominator strategy (everyone appreciates when stuffs blows up real good). As a result, the movies have moved down the quality chain and television has moved up.

Hat tip: Tyler.

*Wall Street II*

It was not a great movie but it was better than I had been expecting and I am glad to have seen it. Moral hazard was explained — well, and using that term – numerous times. The central role of leverage behind the crisis was stressed, as were the political economy elements. The movie was chock full of economics, to a remarkable degree, albeit in an unbalanced fashion, especially when it came to explaining "speculation." The film very well captured the feeling of sick dismay which unfolded with the events of the financial crisis. As an inside joke, they had a wonderful silent stand-in for Geithner. In this movie men don't seem to care about women very much, not even for sex. The Charlie Sheen cameo was my favorite moment, as it rewrites one's understanding of the first Wall Street movie and raises broader questions about the motivations of "good" people. The female lead was flat; I suspect this was poor execution although a Straussian reading will attribute that to a brilliant savaging of her character. I wished for a different ending. A comparison with the parent film shows that New York has become less interesting.

Markets in Everything: Lookup Before You Hookup

Today's dating scene is tough to navigate, which is why Intelius

developed Date Check, a free mobile app that deciphers fact from

fiction in the palm of your hand. Simply enter a name, phone number or

email address and instantly get accurate and comprehensive results.

With features like Sleaze Detector, Compatibility, $$$, Interests and

Living Situation, you can be in the know on the go.

Some of you may recall the scene from Amazon Women on the Moon in which this idea was featured as a joke. I also recall but couldn't find online a scene from the great movie GATTACA in which a women on a date kisses a man and then rushes to the ladies room to have the DNA on her lipstick analyzed for suitable qualities. How long untill we have that technology?

Hat tip: Chris Rasch.

Cineplex hopping, sentences to ponder

The surrealists André Breton and Paul Éluard used to enter movie theaters at random and stay only a little while, until the plot became clear to them and the films’ images were drained of their power. In the Cineplex you can do the same thing all in one building. I did that one day this summer. What I saw was not excerpts from ten different movies, but one movie made up of ten interchangeable parts–the imperial power of Hollywood, still alive and well, surviving postmodern fragmentation and resisting détournement.

Here is the adventure itself. For the pointer I thank Paul Sas.

Comedy recommendations

Steve Hely writes to me:

I'm a real admirer of your blog. You offer such great recommendations. But it seems you rarely recommend any comedy. Are there any books, TV shows, movies, etc. that have made you laugh in recent years?

It's well-known that comedy hits don't usually export well to other countries, because comedy is so culturally specific and also so subjective. So these are not recommendations. What I find funny is this:

1. On TV: Curb Your Enthusiasm and the better ensemble pieces of Seinfeld and also The Ali G Show. The best Monty Python skits are very funny to me, although I find their movies too long and labored. I find stand-up comics funny only when I am there in person.

2. Movies: The last funny movie I saw was I Love You, Man. I like most classic comedies, though without necessarily finding them very funny. Danny Kaye's The Court Jester is a good comedy which most people don't watch any more. I enjoy the chaotic side of W.C. Fields in short doses. Jerry Lewis is funny sometimes, plus there is Pillow Talk. I like the first forty minutes or so of Ferris Bueller. Stardust Memories is my favorite Woody Allen film, though I like many of them.

3. Books: I don't find books of fiction funny, blame it on me. I do find David Hume, and other classic non-fiction authors, to be at times hilarious.

On YouTube, I find the economics comic Yoram Bauman funny. Colbert can be very funny.

I wonder how many dimensions are required to explain or predict a person's taste in comedy?

Andrew Wiles and Fermat’s Last Theorem

Here is one of my all time favorite documentaries, the 45 minute Fermat's Last Theorem made by Simon Singh and John Lynch for the BBC in 1996. I've watched it many times and every time I am moved by unforgettable moments.

The plainspoken Goro Shimura talking of his friend Yutaka Taniyama, "he was not a very careful person as a mathematician, he made a lot of mistakes but he made mistakes in a good direction." "I tried to imitate him," he says sadly, "but I found out that it is very difficult to make good mistakes." Shimura continues to be troubled by his friend's suicide in 1958.

And then there is Andrew Wiles, the frail knight who for seven lonely years pursues the proof that has ensorcelled him since childhood. He announces the proof to the world, is featured on the front page of the New York Times and in People Magazine, he has the respect and admiration of his colleagues and then he discovers the proof is wrong. He works another year trying to fix it but every time he patches one area another fault line opens up. Even speaking of it now you can see and hear his utter despair. It is not too much to imagine that he was on the verge of a breakdown. Unforgettable.

Hat tip to Kottke.

What is emblematic of the 21st century?

A recent reader request was:

What things that are around today are most distinctively 21st century? What will be the answer to this question in 10 years?

Here is what comes to mind and I think most of it will remain emblematic for some time:

Technology: iPhone, Wii, iPad, Kindle. These are no-brainers and I do think it will go down in American history as "iPhone," not "iPhone and other smart phones." Sorry people.

To read: blogs and Freakonomics, this is the age of non-fiction. I don't think we have an emblematic and culturally central novel for the last ten years. The Twilight series is a possible pick but I don't think they will last in our collective memory. Harry Potter (the series started 1997) seems to belong too much to the 1990s.

Films: Avatar, Inception (for appropriately negative reviews of the latter, see here, here, and here). Both will look and feel "of this time." Overall there have been too many "spin-off" movies. Keep in mind this question is not about "what is best."

Music: It's been a slow period, but I'll pick Lady Gaga, most of all for reflecting the YouTube era rather than for her music per se. I don't think many musical performers from the last ten years will become canonical, even though the number of "good songs" is quite high. Career lifecycles seem to be getting shorter, for one thing.

Television: The Sopranos starts in 1999, so it comes closer to counting than Harry Potter does. It reflects "the HBO era." Lost was a major network show and at the very least people will laugh at it, maybe admire it too. Battlestar Galactica. Reality TV.

What am I missing? What does this all add up to? Pretty strange, no?

p.s. Need to add Facebook and Google somewhere!

Official U.S. trailer for *Freakonomics* documentary

You'll find it here. It's a well-done preview, the movie is rated PG-13, and it's from the moviemakers behind the superb King of Kong.

I thank some PR guy for the pointer.

*Agora*

I am surprised this film, set in ancient Alexandria, has not occasioned more controversy. It is the most pro-science, pro-rationalist, anti-Christian movie I have seen — ever. — and it does not disguise the message in the slightest. The director and scriptwriter is Spanish and Chilean, namely Alejandro Amenábar. It offers a Voltairean portrait of Judaism, as an oppressed rabble, most of all responsible for the crime of having birthed Christianity. There are some not-so-subtle parallels shown between the early Christians and current Muslim terrorists.

The visual rendering of antiquity is nicely done and without an excess of CGI.

Here is a positive New York Times review. Here is a positive Guardian review. Not everyone will like this movie.

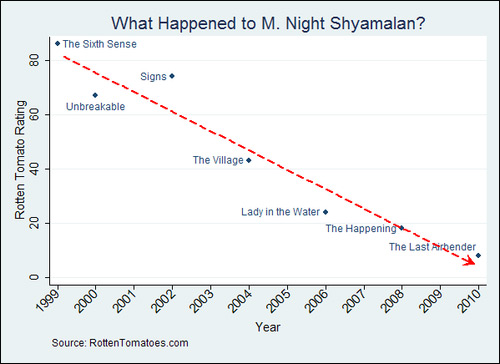

What Happened to M. Night Shyamalan?

Why do we like adventure stories with guides?

Robin Hanson asks:

I’ve been sick, so watched tv more than usual. Watching Journey to the Center of the Earth, I noticed yet again how folks seem to like adventure stories and games to come with guides. People prefer main characters to follow a trail of clues via a map or book written by someone who has passed before, or at least to follow the advice of a wise old person.

Dante of course provides another example, as does Sibyl and Aeneas. And Robin's conclusion?:

This has a big lesson for those who like to think of their real life as a grand adventure: relative to fiction, real grand adventures tend to have fewer guides, and more randomness in success. Real adventurers must accept huge throws of the dice; even if you do most everything right, most likely some other lucky punk will get most of the praise.

If you want life paths that quickly and reliably reveal your skills, like leveling up in video games, you want artificial worlds like schools, sporting leagues, and corporate fast tracks. You might call such lives adventures, but really they pretty much the opposite. If you insist instead on adventuring for real, achieving things of real and large consequence against great real obstacles, well then learn to see the glorious nobility of those who try well yet fail.