Category: Food and Drink

My chat with Brendan Fitzgerald Wallace

He interviewed me, here is his description: “My conversation with economist, author & podcaster Tyler Cowen covering everything from: 1) Buying Land on Mars (for real) 2) Privatizing National Parks 3) Setting up aerial highways in the sky for drone delivery 4) Buying Greenland 5) London post Brexit 6) Universal Basic Income 7) Why Los Angeles is “probably the best city in North America” 8) How real estate can combat social isolation & loneliness 9) Cyber attacks on real estate assets and national security implications. 10) The impacts, positive and negative of Climate Change, on real estate in different geographies. 11) Other esoteric stuff…..”.

Here is the conversation, held in Marina del Rey at a Fifth Wall event.

Those new service sector jobs

Wanted: Restaurant manager. Competitive salary: $100,000.

The six-figure sum is not being offered at a haute cuisine location with culinary accolades, but at fast-food chain Taco Bell. Amid an increasingly tough U.S. labor market, the company is betting a higher salary will help it attract workers and keep them on the team.

The Yum! Brands Inc.-owned chain will test the higher salary in select restaurants in the U.S. Midwest and Northeast, and will also try a new role for employees who want leadership experience but don’t want to be in the management role.

Here is more by Leslie Patton at Bloomberg, via Joe Weisenthal.

“Let them eat Whole Foods!”

This latest front in the food wars has emerged over the last few years. Communities like Oklahoma City, Tulsa, Fort Worth, Birmingham, and Georgia’s DeKalb County have passed restrictions on dollar stores, prompting numerous other communities to consider similar curbs. New laws and zoning regulations limit how many of these stores can open, and some require those already in place to sell fresh food. Behind the sudden disdain for these retailers—typically discount variety stores smaller than 10,000 square feet—are claims by advocacy groups that they saturate poor neighborhoods with cheap, over-processed food, undercutting other retailers and lowering the quality of offerings in poorer communities. An analyst for the Center for Science in the Public Interest, for instance, argues that, “When you have so many dollar stores in one neighborhood, there’s no incentive for a full-service grocery store to come in.” Other critics, like the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, go further, contending that dollar stores, led by the giant Dollar Tree and Dollar General chains, sustain poverty by making neighborhoods seem run-down.

Here is the full article, via Walter Olson.

My Conversation with Abhijit Banerjee

I had an excellent time in this one, here is the audio and transcript. Here is the opening summary:

Abhijit joined Tyler to discuss his unique approach to economics, including thoughts on premature deindustrialization, the intrinsic weakness of any charter city, where the best classical Indian music is being made today, why he prefers making Indian sweets to French sweets, the influence of English intellectual life in India, the history behind Bengali leftism, the best Indian regional cuisine, why experimental economics is underrated, the reforms he’d make to traditional graduate economics training, how his mother’s passion inspires his research, how many consumer loyalty programs he’s joined, and more.

Yes there was plenty of economics, but I feel like excerpting this bit:

COWEN: Why does Kolkata have the best sweet shops in India?

BANERJEE: It’s a bit circular because, of course, I tend to believe Kolkata has —

COWEN: So do I, however, and I have no loyalty per se.

BANERJEE: I think largely because Kolkata actually also — which is less known — has absolutely amazing food. In general, the food is amazing. Relative to the rest of India, Kolkata had a very large middle class with a fair amount of surplus and who were willing to spend money on. I think there were caste and other reasons why restaurants didn’t flourish. It’s not an accident that a lot of Indian restaurants were born out of truck stops. These are called dhabas.

COWEN: Sure.

BANERJEE: Caste has a lot to do with it. But sweets are just too difficult to make at home, even though lots of people used to make some of them. And I think there was some line that was just permitted that you can have sweets made out of — in these specific places, made by these castes.

There’s all kinds of conversations about this in the early-to-mid 19th century on what you can eat out, what is eating out, what can you buy in a shop, et cetera. I think in the late 19th century you see that, basically, sweet shops actually provide not just sweets, but for travelers, you can actually eat a lunch there for 50 cents, even now, an excellent lunch. They’re some savories and a sweet — maybe for 40 rupees, you get all of that.

And it was actually the core mechanism for reconciling Brahminical cultures of different kinds with a certain amount of social mobility. People came from outside. They were working in Kolkata. Kolkata was a big city in India. All the immigrants came. What would they eat? I think a lot of these sweet shops were a place where you actually don’t just get sweets — you get savories as well. And savories are excellent.

In Kolkata, if you go out for the day, the safest place to eat is in a sweet shop. It’s always freshly made savories available. You eat the freshly made savories, and you get some sweets at the end.

COWEN: Are higher wage rates bad for the highest-quality sweets? Because rich countries don’t seem to have them.

BANERJEE: Oh no, rich countries have fabulous sweets. I mean, at France —

COWEN: Not like in Kolkata.

BANERJEE: France has fabulous sweets. I think the US is exceptional in the quality of the . . . let me say, the fact that you don’t get actually excellent sweets in most places —

And this on music:

BANERJEE: Well, I think Bengal was never the place for vocal. As a real, I would say a real addict of vocal Indian classical music, I would say Bengal is not, never the center of . . . If you look at the list of the top performers in vocal Indian classical music, no one really is a Bengali.

In instrumental, Bengal was always very strong. Right now, one of the best vocalists in India is a man who lives in Kolkata. His name is Rashid Khan. He’s absolutely fabulous in my view, maybe the best. On a good day, he’s the best that there is. He’s not a Bengali. He’s from Bihar, I think, and he comes and settles in Kolkata. I think a Hindi speaker by birth, other than a Bengali. So I don’t think Bengal ever had top vocalists.

It had top instrumentalists, and Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar Khan, Nikhil Banerjee — these were all Bengali instrumentalists. Even now, I would say the best instrumentalists, a lot of them are either Bengali or a few of them are second . . . Vilayat Khan and Imrat Khan were the two great non-Bengali instrumentalists of that period, I would say, of the strings especially. And they both settled in Kolkata, so that their children grew up in Kolkata.

And the other great instrumentalists are these Kolkata-born. They went to the same high school as I did. There were these Kolkata-born, not of Bengali families, but from very much the same culture. So I think Kolkata still is the place which produces the best instrumentalists — sitarists, sarod players, et cetera.

COWEN: Why is the better vocal music so often from the South?

Definitely recommended, Abhijit was scintillating throughout.

Airline markets in everything

Out of the many repulsive things about air travel, airline food probably ranks high. But not for AirAsia.

Asia’s largest low-cost carrier is betting people love its food so much that it opened its first restaurant on Monday, offering the same menu it sells on flights. It’s not a gimmick, either: AirAsia, based in Malaysia, said it plans to open more than 100 restaurants globally within the next five years.

The quick-service restaurant’s first location is in a mall in Kuala Lumpur. It’s called Santan, meaning coconut milk in Malay, which is the same branding AirAsia uses on its in-flight menus.

Entrees cost around $3 USD and include local delicacies such as chicken rice and the airline’s signature Pak Nasser’s Nasi Lemak dish, a rice dish with chilli sauce. Locally sourced coffee, teas and desserts are also on the menu.

Here is the full story, via Michael Rosenwald. P.S. Pablo Escobar’s brother is now selling a folding smart phone.

My Conversation with Daron Acemoglu

Self-recommending of course, most of all we talked about economic growth and development, and the history of liberty, with a bit on Turkey and Turkish culture (Turkish pizza!) as well. Here is the audio and transcript. Here is one excerpt, from the very opening:

COWEN: I have so many questions about economic growth. First, how much of the data on per capita income is explained just simply by one variable: distance from the equator? And how good a theory of the wealth of nations is that?

ACEMOGLU: I think it’s not a particularly good theory. If you look at the map of the world and color different countries according to their income per capita, you’ll see that a lot of low-income-per-capita countries are around the equator, and some of the richest countries are pretty far from the equator, in the temperate areas. So many people have jumped to conclusion that there must be a causal link.

But actually, I think geographic factors are not a great explanatory framework for understanding prosperity and poverty.

COWEN: But why does it have such a high R-squared? By one measure, the most antipodal 21 percent of the population produces 69 percent of the GDP, which is striking, right? Is that just an accident?

ACEMOGLU: Yeah, it’s a bit of an accident. Essentially, if you think of which are the countries around the equator that have such low income per capita, they are all former European colonies that have been colonized in a particular way.

And:

COWEN: If we think about the USSR, which has terrible institutions for more than 70 years, an awful form of communism — it falls; there’s a bit of a collapse. Today, they seem to have a higher per capita income than you would expect a priori, if you, just as an economist, write about communism. Isn’t that mostly just because of what is now Russian, or Soviet, human capital?

ACEMOGLU: That’s an interesting question. I think the Russian story is complicated, and I think part of Russian income per capita today is because of natural resources. It’s always a problem for us to know exactly how natural resources should be handled because you can do a lot of things wrong and still get quite a lot of income per capita via natural resources.

COWEN: But if Russians come here, they almost immediately move into North American per capita income levels as immigrants, right? They’re not bringing any resources. They’re bringing their human capital. If people from Gabon come here, it takes them quite a while to get to the —

ACEMOGLU: No, absolutely, absolutely. There’s no doubt that Russians are bringing more human capital. If you look at the Russian educational system, especially during the Soviet time, there was a lot of emphasis on math and physics and some foundational areas.

And there’s a lot of selection among the Russians who come here…

The Conversation is Acemoglu throughout, you also get to hear me channeling Garett Jones. Again, here is Daron’s new book The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty.

Streets Vs Avenues Where to go to dinner in Manhattan model this

Abstract

Yelp data and statistical sampling was used to determine that the average restaurant is better on Manhattan streets than avenues, with an average rating of 3.62 on streets vs 3.49 on avenues. The difference was statistically significant. In addition, you are almost 50% more likely to find an outstanding restaurant while on a street compared to when you are on an avenue. 18% of restaurants on the streets had a score of 4.5 or higher, compared to 13% of restaurants on avenues.

or

From the apparently awesome Alex Bell.

The First Words of Thanksgiving

When the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth rock in 1620 they were cold, hungry and frightened. Imagine their surprise when on March 16 as they unloaded cannon from the Mayflower in preparation for battle an Indian walked into their encampment and asked, “Anyone got a beer?” Seriously, that’s what happened. Samoset, the thirsty Indian, had learned English from occasional fishermen.

Even more fortunate for the Pilgrims was that Somoset was accompanied by Squanto. Squanto had been enslaved 7 years earlier and transported to Spain where he was sold. He then somehow made his way to England and then, amazingly, back to his village in New England around 1619. It’s a horrific story, however, because during his absence Squanto’s entire village and much of the region had been wiped out by disease, almost certainly brought by the Europeans. Nevertheless, in 1621 Squanto was there when the Pilgrims landed and he hammered out an early peace deal and most importantly instructed the settlers how to fertilize their land with fish in order to grow corn.

Squanto instructed them in survival skills and acquainted them with their environment: “He directed them how to set their corn, where to take fish, and to procure other commodities, and was also their pilot to bring them to unknown places for their profit, and never left them till he died.”

Anyone got a beer?

Bonus CWT episode with Fuchsia Dunlop

Here is the transcript and audio, and wonderful photos, over a Chinese meal at Mama Chang in Fairfax, run by the famous Peter Chang. I am not acting as lead interviewer, so this is more like a “Conversation with Tyler chiming in,” nonetheless numerous D.C. area food luminaries are present, as are other members of the Cowen family. Here is one brief excerpt:

T. COWEN: You learned Chinese food in China, of course, much of it in Sichuan province, Hunan province. As Chinese teach food, how is the method of education and training different from, say, Great Britain or the United States?

DUNLOP: Well, I haven’t been to culinary school in Great Britain or the United States, so I’m not sure.

T. COWEN: You’ve been to school in these countries.

DUNLOP: The first thing is that when you go to cooking school, you are learning the building blocks of a cuisine, which is like the grammar of a language. So the basic components, the basic processes and flavors, which you then put together to make a multitude of dishes.

Whereas, I guess, if you were studying French cuisine, you will learn some classic sauces, a bit of knife work, techniques of pastry making. In China, in Sichuan, absolutely fundamental was dao gong (刀工), the knife skills.

[Lydia] CHANG: I actually have a story to share about Dad’s cutting knife. He said when he first started learning, in school, there’s only limited time, but he wants to really excel at it. So he returned back to the dorm, started cutting, using cleaver to cut newspaper to practice.

Some of you will like this a lot, but don’t expect a normal CWT episode. And here is Fuchsia’s wonderful new book The Food of Sichuan, a significantly updated new edition of the old.

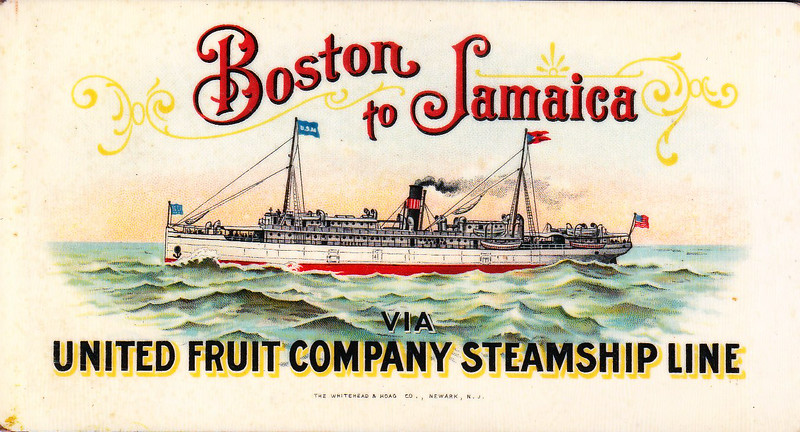

Politically Incorrect Paper of the Day: The United Fruit Company was Good!

The United Fruit Company is the bogeyman of Latin America, the very apotheosis of neo-colonialism. And to be sure in the UFC history there is wrongdoing and plenty of fodder for conspiracy theories but the UFC also brought bananas (as export crop), tourism, and in many cases good governance to parts of Latin America. Much, however, depends on the institutional constraints within which the company operated. Esteban Mendez-Chacon and Diana Van Patten (on the job market) look at the UFC in Costa Rica.

The UFC needed to bring workers to remote locations and thus it invested heavily in worker welfare:

…the UFC invested in sanitation infrastructure, launched health programs, and provided medical attention to its employees. Infrastructure investments included pipes, drinking water systems, sewage system, street lighting, macadamized roads, a dike (Sanou and Quesada, 1998), and by 1942 the company operated three hospitals in the country.

… Given the remoteness the plantations and to reduce transportation costs, the UFC provided the majority of its workers with free housing within the company’s land. This was partially motivated by concerns with diseases like malaria and yellow fever, which spread easily if the population is constantly commuting from outside the plantation. By 1958 the majority of laborers lived in barracks-type structures… [which] exceeded the standards of many surrounding communities (Wiley, 2008).

The UFC wasn’t just interested in healthy workers, they also needed to attract workers with stable families:

The UFC wasn’t just interested in healthy workers, they also needed to attract workers with stable families:

… One of the services that the company provided within its camps was primary education to the children of its employees. The curriculum in the schools included vocational training and before the 1940s, was taught mostly in English. The emphasis on primary education was significant, and child labor became uncommon in the banana regions (Viales, 1998). By 1955, the company had constructed 62 primary schools within its landholdings in Costa Rica (May and Lasso, 1958). As shown in Figure 6a,spending per student in schools operated by the UFC was consistently higher than public spending in primary education between 1947 and 1963.21 On average, the company’s yearly spending was 23% higher than the government’s spending during this period.

…The UFC did not provide directly secondary education although offered some incentives. If the parents could afford the first two years of secondary education of their children in the United States, the UFC paid for the last two years and provided free transportation to and from the United States.

A key driver of UFC investment was that although the UFC was the sole employer within the regions in which it operated, it had to compete to obtain labor from other regions. Thus a 1925 UFC report writes:

We recommend a greater investment in corporate welfare beyond medical measures. An endeavor should be made to stabilize the population…we must not only build and maintain attractive and comfortable camps, but we must also provide measures for taking care of families of married men, by furnishing them with garden facilities, schools, and some forms of entertainment. In other words, we must take an interest in our people if we might hope to retain their services indefinitely.

This is exactly the dynamic which drove the provision of services and infrastructure in unjustly maligned US company towns. It’s also exactly what Rajagopalan and I found in the Indian company town of Jamshedpur, built by Jamshetji Nusserwanji Tata.

The UFC ended in Costa Rica in 1984 but the authors find that it had a long-term positive impact. Using historical records, the authors discover a plausibly randomly-determined boundary line between UFC and non-UFC areas and comparing living standards just inside and just outside the boundary they find that households within the boundary today have better housing, sanitary conditions, education and consumption than households just outside the boundary. Overall:

We find that the firm had a positive and persistent effect on living standards. Regions within the UFC were 26% less likely to be poor in 1973 than nearby counterfactual locations, with only 63% of the gap closing over the following 3 decades.

The paper has appendixes A-J. In one appendix (!), they show using satellite data that regions within the boundary are more luminous at night than those just outside the region. The collection of data is especially notable:

For a better understanding of living standards and investments during UFC’s tenure, we collected and digitized UFC reports with data on wages, number of employees, production, and investments in areas such as education, housing, and health from collections held by Cornell University, University of Kansas, and the Center for Central American Historical Studies. We also use annual reports from the Medical Department of the UFC describing the sanitation and health programs and spending per patient in company-run hospitals from 1912 to 1931. We also collected data from Costa Rican Statistic Yearbooks, which from 1907 to 1917 contain details on the number of patients and health expenses carried out by hospitals in Costa Rica, including the ones ran by the UFC. Export data was also collected from these yearbooks, and from Export Bulletins. 19 agricultural censuses taken between 1900 and 1984 provide information on land use, and we use data from Costa Rican censuses between 1864-1963 to analyze aggregated population patterns, such as migration before and during the UFC apogee, or the size and occupation of the country’s labor force.

Overall, a tremendous paper.

Model this dopamine fast

“We’re addicted to dopamine,” said James Sinka, who of the three fellows is the most exuberant about their new practice. “And because we’re getting so much of it all the time, we end up just wanting more and more, so activities that used to be pleasurable now aren’t. Frequent stimulation of dopamine gets the brain’s baseline higher.”

There is a growing dopamine-avoidance community in town and the concept has quickly captivated the media.

Dr. Cameron Sepah is a start-up investor, professor at UCSF Medical School and dopamine faster. He uses the fasting as a technique in clinical practice with his clients, especially, he said, tech workers and venture capitalists.

The name — dopamine fasting — is a bit of a misnomer. It’s more of a stimulation fast. But the name works well enough, Dr. Sepah said.

The purpose is so that subsequent pleasures are all the more potent and meaningful.

“Any kind of fasting exists on a spectrum,” Mr. Sinka said as he slowly moved through sun salutations, careful not to get his heart racing too much, already worried he was talking too much that morning.

Here is more from Nellie Bowles at the NYT.

Learning is Caring: An Agrarian Origin of American Individualism

I am looking forward to reading this one, from Itzchak Tzachi Raz, who is on the job market from Harvard this year:

This study examines the historical origins of American individualism. I test the hypothesis that local heterogeneity of the physical environment limited the ability of farmers on the American frontier to learn from their successful neighbors, turning them into self-reliant and individualistic people. Consistent with this hypothesis, I find that current residents of counties with higher agrarian heterogeneity are more culturally individualistic, less religious, and have weaker family ties. They are also more likely to support economically progressive policies, to have positive attitudes toward immigrants, and to identify with the Democratic Party. Similarly, counties with higher environmental heterogeneity had higher taxes and a higher provision of public institutions during the 19th century. This pattern is consistent with the substitutability of formal and informal institutions as means to solve collective action problems, and with the association between “communal” values and conservative policies. These findings also suggest that, while understudied, social learning is an important determinant of individualism.

Here is the home page, the paper is not yet available. Here is his actual job market paper, on adverse possession. I do hope the author lets me know once this paper is ready, I am very much looking forward to reading it.

Can you impose pecuniary externalities upon Korean squirrels?

Look out, squirrels of the world. It turns out acorns are good for humans, too.

Here in South Korea, the popularity of acorn noodles, jelly and powder has exploded in recent years, after researchers declared the nuts a healthy “superfood” that can help fight obesity and diabetes.

In the U.S., where some Native Americans once made acorns a staple of their diet, restaurants and health-conscious blogs are starting to explore recipes for acorn crackers, acorn bread and acorn coffee.

That is bad news for squirrels and other animals that rely on oak trees for sustenance. In South Korea, where human foraging has multiplied, there are now fewer acorns on the ground, and the squirrel population has dwindled.

Is this a reductio ad absurdum of the idea that pecuniary externalities are irrelevant? Ask your friendly neighborhood squirrel! If you can find him, that is. Then there is this:

Safeguarding acorns for squirrels is proving to be a tough nut to crack. That’s where the Acorn Rangers come in.

Formed at Seoul’s Yonsei University, the nascent Acorn Rangers group polices the bucolic campus, scaring off other humans from swiping squirrel food. Taking up the cause are students like Park Ji-eun, who skipped lunch on a recent day so a squirrel could eat this winter.

Strolling across campus, Ms. Park, a junior, sprung into action after spotting an acorn assailant: a woman in her early 60s, clutching a plastic bag stuffed with the tree nuts.

“The squirrels will starve!” barked Ms. Park, her voice booming so loudly that other acorn hunters—human ones—scurried away. The two argued for nearly an hour until Ms. Park emerged with the plastic bag in hand.

Here is the full WSJ story, by Dasl Yoon and Na-Young Kim, via the excellent Samir Varma.

My Conversation with Ben Westhoff

Truly an excellent episode, Ben is an author and journalist. Here is the audio and transcript, covering most of all the opioid epidemic and rap music, but not only.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: But if so much fentanyl comes from China, and you can just send it through the mail, why doesn’t it spread automatically wherever it’s going to go? Is it some kind of recommender network? It wouldn’t seem that it’s a supply constraint. It’s more like someone told you about a restaurant they ate at last night.

WESTHOFF: It’s because the Mexican cartels are still really strongly in the trade. Even though it’s all made in China, much of it is trafficked through the cartels, who buy the precursors, the fentanyl ingredients, from China, make it the rest of the way. Then they send it through the border into the US.

You can get fentanyl in the mail from China, and many people do. It comes right to your door through the US Postal Service. But it takes a certain level of sophistication with the drug dealers to pull that off.

COWEN: It’s such a big life decision, and it’s shaped by this very small cost of getting a package from New Hampshire to Florida. What should we infer about human nature as a result of that? What’s your model of the human beings doing this stuff if those geographic differences really make the difference for whether or not you do this and destroy your life?

WESTHOFF: Well, everything is local, right? Not just politics. You’re influenced by the people around you and the relative costs. In St. Louis, it’s so incredibly cheap, like $5 to get some heroin, some fentanyl. I don’t know how it works in, say, New Hampshire, but I know in places like West Virginia, it’s still a primarily pill market. People don’t use powdered heroin, for example. For whatever reason, they prefer Oxycontin. So that has affected the market, too.

And:

COWEN: Did New Zealand do the right thing, legalizing so many synthetic drugs in 2013?

WESTHOFF: I absolutely think they did. It was an unprecedented thing. Now drugs like marijuana, cocaine, heroin, all the drugs you’ve heard of, are internationally banned. But what New Zealand did was it legalized these forms of synthetic marijuana. So synthetic marijuana has a really bad reputation. It goes by names like K2 and Spice, and it’s big in homeless populations. It’s causing huge problems in places like DC.

But if you make synthetic marijuana right, as this character in my book named Matt Bowden was doing in New Zealand, you can actually make it so it’s less toxic, so it’s somewhat safe. That’s what he did. They legalized these safer forms of it, and the overdose rate plummeted. Very shortly thereafter, however, they banned them again, and now deaths from synthetic marijuana in New Zealand have gone way up.

COWEN: And what about Portugal and Slovenia — their experiments in decriminalization? How have those gone?

WESTHOFF: By all accounts, they’ve been massive successes. Portugal had this huge problem with heroin, talking like one out of every 100 members of the population was touched by it, or something like that. And now those rates have gone way down.

In Slovenia, they have no fentanyl problem. They barely have an opioid problem. Their rates of AIDS and other diseases passed through needles have gone way down.

And on rap music:

COWEN: This question is maybe a little difficult to explain, but wherein lies the musical talent of hip-hop? If we look at Mozart, there’s melody, there’s harmony. If you listen to Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, it’s something very specifically rhythmic, and the textures, and the organization of the blocks of sound. The poetry aside, what is it musically that accounts for the talent in rap music?

WESTHOFF: First of all, riding a beat, rapping, if you will, is extremely hard, and anyone who’s ever tried to do it will tell you. You have to have the right cadence. You have to have the right breath control, and it’s a talent. There’s also — this might sound trivial, but picking the right music to rap over.

So hip-hop, of course, is a genre that’s made up of other genres. In the beginning, it was disco records that people used. And then jazz, and then on and on. Rock records have been rapped over, even. But what song are you going to pick to use? And if someone has a good ear for a sound that goes with their style, that’s something you can’t teach.

And yes on overrated vs. underrated, you get Taylor Swift, Clint Eastwood, and Seinfeld, among others. I highly recommend all of Ben’s books, but most of all his latest one Fentanyl, Inc.: How Rogue Chemists Are Creating the Deadliest Wave of the Opioid Epidemic.

My Conversation with Alain Bertaud

Excellent throughout, Alain put on an amazing performance for the live audience at the top floor of the Observatory at the old World Trade Center site. Here is the audio and transcript, most of all we talked about cities. Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Will America create any new cities in the next century? Or are we just done?

BERTAUD: Cities need a good location. This is a debate I had with Paul Romer when he was interested in charter cities. He had decided that he could create 50 charter cities around the world. And my reaction — maybe I’m wrong — but my reaction is that there are not 50 very good locations for cities around the world. There are not many left. Maybe with Belt and Road, maybe the opening of Central Asia. Maybe the opening of the ocean route on the northern, following the pole, will create the potential for new cities.

But cities like Singapore, Malacca, Mumbai are there for a good reason. And I don’t think there’s that many very good locations.

COWEN: Or Greenland, right?

[laughter]

BERTAUD: Yes. Yes, yes.

COWEN: What is your favorite movie about a city? You mentioned a work of fiction. Movie — I’ll nominate Escape from New York.

[laughter]

BERTAUD: Casablanca.

Here is more:

COWEN: Your own background, coming from Marseille rather than from Paris —

BERTAUD: I would not brag about it normally.

[laughter]

COWEN: But no, maybe you should brag about it. How has that changed how you understand cities?

BERTAUD: I’m very tolerant of messy cities.

COWEN: Messy cities.

BERTAUD: Yes.

COWEN: Why might that be, coming from Marseille?

BERTAUD: When we were schoolchildren in Marseille, we were used to a city which has a . . . There’s only one big avenue. The rest are streets which were created locally. You know, the vernacular architecture.

In our geography book, we had this map of Manhattan. Our first reaction was, the people in Manhattan must have a hard time finding their way because all the streets are exactly the same.

[laughter]

BERTAUD: In Marseille we oriented ourselves by the angle that a street made with another. Some were very narrow, some very, very wide. One not so wide. But some were curved, some were . . . And that’s the way we oriented ourselves. We thought Manhattan must be a terrible place. We must be lost all the time.

Finally:

COWEN: And what’s your best Le Corbusier story?

BERTAUD: I met Le Corbusier at a conference in Paris twice. Two conferences. At the time, he was at the top of his fame, and he started the conference by saying, “People ask me all the time, what do you think? How do you feel being the most well-known architect in the world?” He was not a very modest man.

[laughter]

BERTAUD: And he said, “You know what it feels? It feels that my ass has been kicked all my life.” That’s the way he started this. He was a very bitter man in spite of his success, and I think that his bitterness is shown in his planning and some of his architecture.

COWEN: Port-au-Prince, Haiti — overrated or underrated?

Strongly recommended, and note that Bertaud is eighty years old and just coming off a major course of chemotherapy, a remarkable performance.

Again, I am very happy to recommend Alain’s superb book Order Without Design: How Markets Shape Cities.