Category: Medicine

Mood affiliation isn’t always bad

That was my response to reading Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me. We all overinvest in non-diversified mood affiliation portfolios, so why not read someone else’s non-diversified mood affiliation portfolio from a less common point of view?

The writing I thought was superb and also original, so I agree with the take of Christopher Hayes on Twitter:

Read

@tanehisicoates book because the writing itself is in many ways more important and essential than the *argument* it’s making.

Many of you will object to this book, and not entirely for incorrect reasons. This is a fire hose but there is not much if any engagement with potentially contradictory facts. And if you read only this book, and otherwise would know nothing of America, you would not come close to guessing national black per capita income.

Still, if you’re wondering whether or not you should pick it up, I will nudge you in the direction of “yes.”

Here is a good article on the author.

New interview with Ben Goldacre

Here is one good bit of many:

I have a deep-rooted prejudice which is that if people can talk fluently in everyday language about their job, it strongly suggests that they have fully incorporated their work into their character. They feel it in their belly. There are people with whom you talk about technical stuff and it almost feels like they can only talk about it in a very formal way with their best work face on – as if the information they are talking about has not penetrated within. Twitter cuts through that and is a way of finding people who are insightful and passionate about what they do, like junior doctors one year out of medical school who take you aback when you realise they know more than people whose job it is to know about a particular field, such as 15 year-old Rhys Morgan. He has Crohn’s disease and went onto Crohn’s disease discussion forums and discussed evidence, whilst noting down people making false claims about evidence for proprietary treatments. He ended up giving better critical appraisal of the evidence that was presented than plenty of medical students. This was all simply because he read How to Read a Paper by Trish Greenhalgh and some of my writings, so he has learnt about how critical appraisal works and what trials look like along with the strengths and weaknesses of different kinds of evidence. Thanks to Twitter, I have been able to read about people like Rhys in action and to see ideas and principles really come alive and be discussed and for that, it is wonderful.

For the pointer I thank Michelle Dawson.

The economics of biosimilars

If I understand correctly, a biologic is “any medicinal product manufactured in, extracted from, or semisynthesized from biological sources,” and a biosimilar is a copy of a biologic. Think of a biosimilar as harder to make than a generic drug and also requiring separate FDA approval. Here is Wikipedia:

Unlike the more common small-molecule drugs, biologics generally exhibit high molecular complexity, and may be quite sensitive to changes in manufacturing processes. Follow-on manufacturers do not have access to the originator’s molecular clone and original cell bank, nor to the exact fermentation and purification process, nor to the active drug substance. They do have access to the commercialized innovator product.

Here is a Rand piece on the potential cost savings from biosimilars (pdf), but in percentage terms they do not become nearly as cheap as generic drugs, maybe 65-85% of the price of the original.

Zarxio was the first biosimilar approved by the United States, and the global biosimilars market could hit $55 billion by 2020. Here is yesterday’s FT story about biosimilars draining away sales.

Here is a paper by Blackstone and Fuhr:

Various factors, such as safety, pricing, manufacturing, entry barriers, physician acceptance, and marketing, will make the biosimilar market develop different from the generic market. The high cost to enter the market and the size of the biologic drug market make entry attractive but risky.

Will cell therapies, which are relatively new and also hard to copy with biosimilars, save Big Pharma from the forthcoming patent cliff?

Biosimilars will become a bigger issue soon:

There are 11 biologic drugs that will face biosimilar competition in the next several years, according to data compiled by Evercore ISI. These drugs, which treat ailments from cancer to rheumatoid arthritis, raked in more than $50 billion combined in 2014.

The FDA is outlining biosimilar approval pathways, although the issue seems to be receiving almost zero attention from the outside world.

Undetached tiger part to the rescue?

Fewer than 4,000 tigers roam across the Asian continent today, compared to about 100,000 a century ago. But researchers are proposing a new way to protect the big cats: redefine them.

The proposal, published this week in Science Advances, argues current taxonomy of the species is flawed, making global conservation efforts unnecessarily difficult.

There are up to nine commonly accepted subspecies of tigers in the world, three of which are extinct. But the scientists’ analysis, conducted over a course of several years, claims there are really only two tiger subspecies: one found on continental Asia and another from the Indonesian islands of Sumatra, Java and Bali.

If the tiger is redefined more broadly, the emphasis can be on saving tigers as a whole, rather than having to treat subpopulations in very particular and sometimes inefficient ways. Monetary theory enters into this problem as well:

At the heart of the debate is a concept called “taxonomic inflation,” or the massive influx of newly recognized species and subspecies. Some critics blame the trend in part on emerging methods of identifying species through ancestry and not physical traits. Others point to technology that has allowed scientists to distinguish between organisms at the molecular level.

[Nearly 200,000 ‘new’ marine species turn out to be duplicates]

“There are so many species concepts that you could distinguish each population separately,” Wilting said. “Not everything you can distinguish should be its own species.”

That is all from Robert Gebelhoff.

Why is Obamacare still unpopular?

After all of this and two complete open enrollments, only 40% of those who are eligible for Obamacare have signed up—far below the proportion of the market insurers have historically needed to assure a sustainable risk pool.

If this were a private enterprise enjoying these kinds of benefits [ namely legal coercion], and only sold its product to 40% of the market, its CEO would be fired.

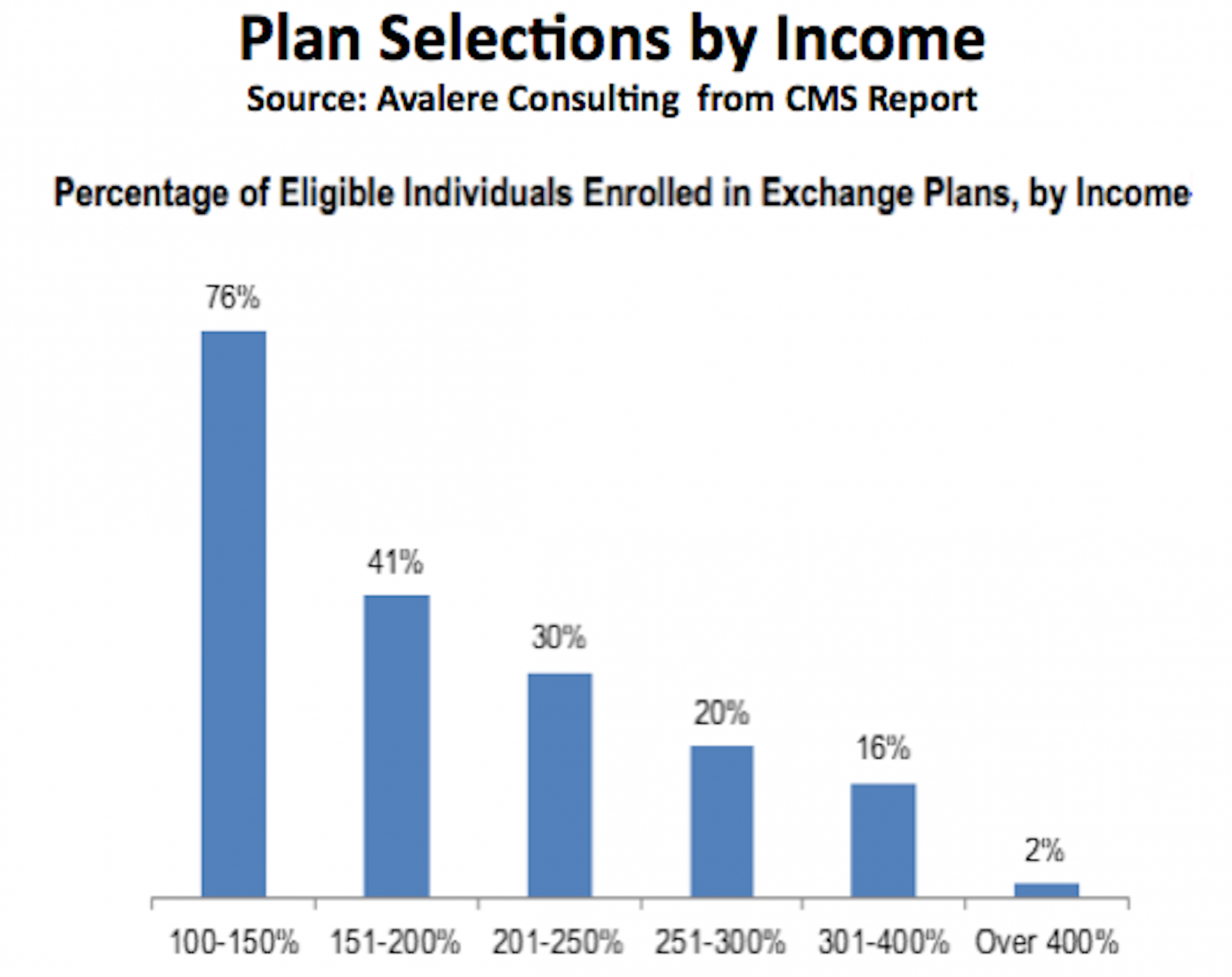

Looking at this picture, only 20% of those eligible for Obamacare, who make between 251% and 300% of the poverty level, bought Obamacare. Why?

The Obama administration will in fact be increasing the subsidies it will pay to insurance companies.

King vs. Burwell, and other stuff

I have not been a fan of Obamacare, which I consider to be a highly inefficient form of wealth insurance. Nonetheless, had this decision gone the other way at this point we would have ended up with something worse, or ended back at “Obamacare as know it,” but only after a lot of political stupidity and also painful media coverage. So on net I take this to be good news, although arguably it is bad news that it is good news.

From the decision, insurers gained $3 billion in market value, and hospital stocks surged about ten percent, make of that what you will.

I found the remarks of Robert Laszlewski to be most to the point. Philip Wallach had some excellent legal and constitutional points, see also Cass Sunstein. I am very much a legal outsider, but it seems to me this does indeed rejigger something or other looking forward.

Elsewhere in the world, Schaueble does his best Scalia impression and tells us that June 30 is June 30, not July 1. Greece hasn’t exploded — yet — and everyone is wondering how much time is left on the shot clock. I’m still predicting an agreement, albeit one which will break pretty quickly.

TPP received fast track approval.

It’s been one of the best political weeks in years, although disconcertingly most of the good news has been avoiding even worse outcomes, not actual forward political progress of the kind one would like to be celebrating.

In Berlin, you can rent the smallest house in the world for one euro a night. And here is a baby owl, learning to fly, or so one would expect.

What they say about you when you are not listening

An operation was inadvertently recorded, and here are some of the results:

The recording captured Ingham mocking the amount of anesthetic needed to sedate the man, the lawsuit states, and Shah then commented that another doctor they both knew “would eat him for lunch.”

The discussion soon turned to the rash on the man’s penis, followed by the comments implying that the man had syphilis or tuberculosis. The doctors then discussed “misleading and avoiding” the man after he awoke, and Shah reportedly told an assistant to convince the man that he had spoken with Shah and “you just don’t remember it.” Ingham suggested Shah receive an urgent “fake page” and said, “I’ve done the fake page before,” the complaint states. “Round and round we go. Wheel of annoying patients we go. Where it’ll land, nobody knows,” Ingham reportedly said.

Ingham then mocked the man for attending Mary Washington College, once an all-women’s school, and wondered aloud whether her patient was gay, the suit states. Then the anesthesiologist said, “I’m going to mark ‘hemorrhoids’ even though we don’t see them and probably won’t,” and did write a diagnosis of hemorrhoids on the man’s chart, which the lawsuit said was a falsification of medical records.

After declaring the patient a “big wimp,” Ingham reportedly said: “People are into their medical problems. They need to have medical problems.”

Shah replied, “I call it the Northern Virginia syndrome,” according to the suit.

There is more here, from Tom Jackman, stunning throughout. For the pointer I thank Michael Rosenwald.

Is there a new Obamacare political equilibrium?

A Supreme Court ruling could gut an important facet of the Affordable Care Act as early as this week, but you wouldn’t know it from what the Republican presidential candidates have been talking about.

In the lead-up to the key 2012 Supreme Court ruling on health care reform – in which the justices decided the penalty paid by anyone without health coverage was a tax, and therefore constitutional – Republicans were abuzz about the possibility that the law could be overturned, and the issue featured prominently in campaign trail rhetoric.

But this time the GOP candidates for president have uttered barely a peep, even though the high court could decide the federal government cannot subsidize health insurance purchased through the federal exchange, which would leave millions of people without insurance and effectively unravel Obamacare as we know it.

That is from Rebecca Berg.

The extreme durability of Lebron James

Over the past five seasons, LeBron’s played a total of 18,087 minutes, counting the regular season and the playoffs.

What that means: Compared to every other player, LeBron’s played at least 15% more minutes than anyone else in the league. He’s played nearly 2,500 more minutes than Kevin Durant, the runner-up.

Basically, pick any other NBA player. Since 2010, LeBron has played the equivalent of at least one extra season compared to that player — and likely, a lot more.

And over the past ten seasons, the minutes gap widens — LeBron has a 20% edge on Joe Johnson (who’s played the second-most minutes) and a 30% edge on Tim Duncan (who’s played the tenth-most).

And yet that is with very little in the way of injury, perhaps his most remarkable achievement. That is all from Dan Diamond.

The Hidden World of Matchmaking and Market Design

Al Roth’s Who Gets What and Why: The Hidden World of Matchmaking and Market Design is an excellent addition to the pantheon of popular economics books. It’s engagingly written, covers new material and will be of interest to professional economists as well as to the broader audience of intelligent readers.

I review the book more extensively for the Wall Street Journal. (Google the title, Matchmaker, Make Me a Market to get beyond the paywall for non-subscribers). Roth is well known for helping to design kidney swaps–when donor A and patient A’ and donor B and patient B’ are mismatched it may yet be possible for A to give to B’ and B to give to A’.

Mr. Roth, however, wants to go further. The larger the database, the more lifesaving exchanges can be found. So why not open U.S. transplants to the world? Imagine that A and A´ are Nigerian while B and B´ are American. Nigeria has virtually no transplant surgery or dialysis available, so in Nigeria patient A’ will die for certain. But if we offered a free transplant to him, and received a kidney for an American patient in return, two lives would be saved.

The plan sounds noble but expensive. Yet remember, Mr. Roth says, “removing an American patient from dialysis saves Medicare a quarter of a million dollars. That’s more than enough to finance two kidney transplants.” So offering a free transplant to the Nigerian patient can save money and lives.

It’s hard to think of a better example of gains from trade (or a better PR coup for the U.S. on the world stage).

One of the most interesting aspects of the book is that Roth has created a new typology of market failure but a very different way of addressing such market failures. Read the whole review for more.

Do IP rights matter for health care markets?

Heidi L. Williams says yes:

A long theoretical literature has analyzed optimal patent policy design, yet there is very little empirical evidence on a key parameter needed to apply these models in practice: the relationship between patent strength and research investments. I argue that the dearth of empirical evidence on this question reflects two key challenges: the difficulty of measuring specific research investments, and the fact that finding variation in patent protection is difficult. I then summarize the findings of two recent studies which have made progress in starting to overcome these empirical challenges by combining new datasets measuring biomedical research investments with novel sources of variation in the effective intellectual property protection provided to different inventions. The first study, Budish, Roin, and Williams (forthcoming), documents evidence consistent with patents affecting the rate and direction of research investments in the context of cancer drug development. The second study, Williams (2013), documents evidence that one form of intellectual property rights on the human genome had quantitatively important impacts on follow-on scientific research and commercial development. I discuss the relevance of both studies for patent policy, and discuss directions for future research.

The NBER link is here.

Interpreting the results of the Oregon Medicaid experiment

There is a new and probably very important paper by Amy Finkelstein, Nathaniel Hendren, and Erzo F.P. Luttmer:

We develop and implement a set of frameworks for valuing Medicaid and apply them to welfare analysis of the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment, a Medicaid expansion that occurred via random assignment. Our baseline estimates of the welfare bene fit to recipients from Medicaid per dollar of government spending range from about $0.2 to $0.4, depending on the framework, with a relatively robust lower bound of about $0.15. At least two- fifths – and as much as four- fifths – of the value of Medicaid comes from a transfer component, as opposed to its ability to move resources across states of the world. In addition, we estimate that Medicaid generates a substantial transfer to non-recipients of about $0.6 per dollar of government spending.

An implication of this is that the poor would be better off getting direct cash transfers: “Our welfare estimates suggest that if (counterfactually) Medicaid recipients had to pay the government’s cost of their Medicaid, they would not be willing to do so.”

And perhaps this sentence could use the “rooftops treatment”:

It is a striking finding that Medicaid transfers to non-recipients are large relative to the benefits to recipients; depending on which welfare approach is used, transfers to non-recipients are between one-and-a-half and three times the size of benefits to recipients.

Or this:

Across a variety of alternative specifications, we consistently find that Medicaid’s value to recipients is lower than the government’s costs of the program, and usually substantially below. This stands in contrast to the current approach used by the Congressional Budget Office to value Medicaid at its cost. It is, however, not inconsistent with the few other attempts we know of to formally estimate a value for Medicaid; these are based on using choices to reveal ex-ante willingness to pay, and tend to fi nd estimates (albeit for different populations) in the range of 0.3 to 0.5.

Princeton University Press to the rescue

Thrive: How Better Mental Health Care Transforms Lives and Saves Money, by Richard Layard & David M. Clark.

Mental illness is a leading cause of suffering in the modern world. In sheer numbers, it afflicts at least 20 percent of people in developed countries. It reduces life expectancy as much as smoking does, accounts for nearly half of all disability claims, is behind half of all worker sick days, and affects educational achievement and income. There are effective tools for alleviating mental illness, but most sufferers remain untreated or undertreated. What should be done to change this? In Thrive, Richard Layard and David Clark argue for fresh policy approaches to how we think about and deal with mental illness, and they explore effective solutions to its miseries and injustices.

Layard and Clark show that modern psychological therapies are highly effective and could potentially turn around the lives of millions of people at little or no cost. This is because treating psychological problems generates huge savings on physical health care, as well as massive economic savings through more people working. So psychological therapies would effectively pay for themselves, generating potential savings for nations the world over. Layard and Clark describe how various successful psychological treatments have been developed and explain what works best for whom. They also discuss how mental illness can be prevented through better schools and a better society, and the urgency of doing so.

My earlier post on mental illness is here, and so I am not sure I will agree with this book — we will see. Here is a related recent publication by Layard.

Optimal policy toward mental illness

I was asked about this recently, so I thought I would put down some basic thoughts. Note that mental illness is a major underlying issue behind both crime and unemployment. Federal, state, and local policies toward the mentally ill are highly complex, but here are a few points:

1. As is often the case in health care policy, my inclination is to fund research and development, in this case through the NIH and NSF, before worrying about improving coverage in extant programs. The long-term dynamic gains have the potential to outweigh the one-time static gains.

2. Medicaid offers a highly imperfect coverage of mental illness. Fine-tuning the coverage may well be a good idea, but perhaps first Medicaid needs to be put on a sounder footing. If you are a liberal this may mean federalizing Medicaid, and if you are a conservative this may mean block grants to the states for Medicaid experimentation. If we are simply asking which policy is better for the mentally ill, federalization is likely the answer, although that does not settle the broader debate as to which alternative would be better overall.

3. We could retool Obamacare mandates, and other health insurance default settings, to have more coverage for mental illness and less coverage for other health conditions. Both practical and “individual responsibility” arguments might point in that direction.

4. The deinstitutionalization of the 1980s has come in for a lot of criticism, but I remain a fan of that policy. I’m well aware of its connection to homelessness, and also how many mentally ill people have ended up in jail. Still, that change ended a kind of slavery for many, and if you oppose slavery you should oppose the previous policies, even if the transition brought some very large practical problems. Of course some of these people were lobotomized or otherwise treated coercively in addition to their involuntary confinement. In 1955 the institutionalized population peaked at about 500,000 and many of those were not voluntary admissions; a 2003 measure put that same population at only 50,000. I recommend this Samuel R. Bagenstos piece on the topic.

5. Further deregulation could boost telemedicine and also telepsychiatry; this would lower cost and is especially important for rural areas.

6. When the family of a mentally ill adult should be notified, given individual privacy rights, is worth further discussion. I don’t have a simple answer, here is some background.

7. The future debate will be all about wearables, including those that monitor the excited or violent states of mentally ill people. I am skeptical about this development, mostly for slippery slope reasons, but this will become a major policy issue, for criminals and high risk individuals too.

8. Crime rates have been falling since the 1980s. That suggests some very large gains are coming through peer effects. There is plenty of evidence that mentally ill people, to some extent, slot into their culture’s conception of what mental illness should consist of (mentally ill Malaysians for instance are more likely to “run amok,” because that is a salient concept there.) It seems that our culture is communicating an increasingly peaceful notion of what mental illness should consist of. This development should be studied further, as perhaps those gains can be extended or accelerated in some way.

Overall this is one of the most important topics which is most understudied by economists.

HIPAA, the Police, and Goffman’s On the Run

Some people are calling Steven Lubet’s new review of Alice Goffman’s On the Run “troubling” and even “devastating” but I am non-plussed. Lubet questions the plausibility of some of Goffman’s accounts:

She describes in great detail the arrest at a Philadelphia hospital of one of the 6th Street Boys who was there with his girlfriend for the birth of their child. In horror, Goffman watched as two police officers entered the room to place the young man in handcuffs, while the new mother screamed and cried, “Please don’t take him away. Please, I’ll take him down there myself tomorrow, I swear – just let him stay with me tonight.” (p. 34). The officers were unmoved; they arrested not only Goffman’s friend, but also two other new fathers who were caught in their sweep.

How did the policemen know to look for fugitives on the maternity floor? Goffman explains:

According to the officers I interviewed, it is standard practice in the hospitals serving the Black community for police to run the names of visitors or patients while they are waiting around, and to take into custody those with warrants . . . .

The officers told me they had come into the hospital with a shooting victim who was in custody, and as was their custom, they ran the names of the men on the visitors’ list.

This account raises many questions. Even if police officers had the time and patience to run the names of every patient and visitor in a hospital, it would violate the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) for the hospital simply to provide an across-the-board list….

In addition, Lubet contacted a source in the Philadelphia police department and asked if there was any such policy.

When I asked if her account was possible, he said, “No way. There was never any such policy or standard practice.” In addition, he told me that all of the trauma centers in Philadelphia – where police are most likely to be “waiting around,” as Goffman put it, for prisoners or shooting victims – have always been extremely protective of their patient logs. He flatly dismissed the idea that such lists ever could have been available upon routine request as Goffman claims. “That’s outlandish,” he said.

It would also be outlandish for police to beat and kill people without cause but since Goffman’s book has appeared we have plenty of video evidence that the type of actions she claims to have witnessed do in fact happen.

Moreover, HIPAA does not provide privacy against the police. HIPAA was written specifically so that the police can request information from hospitals. Here is the ACLU on HIPAA:

Q: Can the police get my medical information without a warrant?

A: Yes. The HIPAA rules provide a wide variety of circumstances under which medical information can be disclosed for law enforcement-related purposes without explicitly requiring a warrant.[iii] These circumstances include (1) law enforcement requests for information to identify or locate a suspect, fugitive, witness, or missing person (2) instances where there has been a crime committed on the premises of the covered entity, and (3) in a medical emergency in connection with a crime.[iv]

In other words, law enforcement is entitled to your records simply by asserting that you are a suspect or the victim of a crime.

Finally, the records in question in this case were not even patient records but visitor records. Whether or not there is an official policy on what to do while waiting at a hospital for other reasons (say to speak to a suspect) it’s plausible to me that the police in Philadelphia can and do sneak a peek at visitor records when the opportunity arises. It’s certainly the case that people who have warrants against them avoid hospitals and other institutions that keep such records for fear of arrest (and here).

I was confused by Lubet’s other big reveal, “Goffman appears to have participated in a serious felony in the course of her field work – a circumstance that seems to have escaped the notice of her teachers, her mentors, her publishers, her admirers, and even her critics.” But this didn’t escape my notice. How could it? Goffman’s crime is the climax of the book! Lubet is talking about Goffman’s action after her friend, Chuck, is murdered:

…This time, Goffman did not merely take notes – on several nights, she volunteered to do the driving. Here is how she described it:

We started out around 3:00 a.m., with Mike in the passenger seat, his hand on his Glock as he directed me around the area. We peered into dark houses and looked at license plates and car models as Mike spoke on the phone with others who had information about [the suspected killer’s] whereabouts.

One night, Mike thought he saw his target:

He tucked his gun in his jeans, got out of the car, and hid in the adjacent alleyway. I waited in the car with the engine running, ready to speed off as soon as Mike ran back and got inside (p. 262).

Fortunately, Mike decided that he had the wrong man, and nobody was shot that night.

The fact that Goffman had become one of the gang is the point. A demonstration that environment trumps upbringing. She only narrowly escaped becoming trapped by the luck of the victim’s absence. The sociology professor and the thug, entirely different lives, separated by the thinnest of margins.