Category: Medicine

Medical markets in everything?

Or will they be thwarted?

To Nina McCollum, Cleveland Clinic’s decision to begin billing for some email correspondence between patients and doctors “was a slap in the face.”

She has relied on electronic communications to help care for her ailing 80-year-old mother, Penny Cooke, who is in need of specialized psychiatric treatment from the clinic. “Every 15 or 20 dollars matters, because her money is running out,” she said.

Electronic health communications and telemedicine have exploded in recent years, fueled by the coronavirus pandemic and relaxed federal rules on billing for these types of care. In turn, a growing number of health care organizations, including some of the nation’s major hospital systems like Cleveland Clinic, doctors’ practices and other groups, have begun charging fees for some responses to more time-intensive patient queries via secure electronic portals like MyChart.

…a new study shows that the fees, which some institutions say range from a co-payment of as little as $3 to a charge of $35 to $100, may be discouraging at least a small percentage of patients from getting medical advice via email. Some doctors say they are caught in the middle of the debate over the fees, and others raised concerns about the effects that the charges might have on health equity and access to care.

Demand curves do slope downward. And yet:

But a recent study led by Dr. Holmgren of data from Epic, a dominant electronic health records company, showed that the rate of patient emails to providers had increased by more than 50 percent in the last three years.

Perhaps there is a smidgen of room for AI here? But not under the current legal regime, I suspect. Here is the full Benjamin Ryan NYT article.

The medical culture that is Britain

Universities have been told they must limit the number of medical school places this year or risk fines, a move attacked as “extraordinary” when the NHS is struggling with staff shortages.

Medical schools have been told to curtail offers to ensure that there is “no risk” of them accepting more would-be doctors than permitted by a government cap, with universities saying they are likely to offer fewer places than normal to sixth-formers this year.

Ministers have been criticised for holding firm to a 7,500 cap on new medical students in England while also acknowledging that a chronic shortage of doctors and nurses is contributing to long delays for NHS treatment.

Robert Halfon, the universities minister, wrote to vice-chancellors last week telling them to limit their offers to sixth-formers, causing frustration among universities, which face fines of £100,000 per student for persistent over-recruitment. Universities say that in the summer, they were forced to reject students for administrative reasons such as submitting vaccine certificates late to stay within permitted numbers.

Here is more from the Times of London (gated). Perhaps Tyrone approves!

Is the NHS the UK’s biggest problem?

UK ambulances took an average of 1 hour & 32 minutes to respond to heart attacks & strokes last month. 5 X higher than target, double the average in November. Feels like the NHS is falling apart

That is from Matt Goodwin.

Some Ukrainian refugees in the UK are returning back home to get medical care, because their pledge of NHS coverage has turned out to be very meaningful.

I think one has to face the possibility that the NHS has fallen apart, and “all the King’s horses and all the King’s men…” etc. To make it all much worse, the British citizenry is convinced that it can get a great product for nearly free. How will the news be broken to voters?

I don’t see much coverage of this in the MSM, but here is Bloomberg reporting on Peter Thiel:

[Thiel] has described British people’s affection for the state-backed health service as “Stockholm syndrome.”

The venture capitalist’s comments came during a Q&A session after a speech at the Oxford Union, a 200-year-old debating society, on Monday. He also said that the crisis-stricken health service, currently grappling with strikes and long wait times for emergency care, was making people sick and needs “market mechanisms” to fix it. Such mechanisms include privatizing parts of it, avoiding rationing and loosening regulations…

“In theory, you just rip the whole thing from the ground and start over,” Thiel said after an address in which he argued that a perceived fear of disruption was holding back technological and scientific developments. “In practice, you have to somehow make it all backwards-compatible in all these ridiculous British ways.”

The first step to fixing the NHS was, he said, to break away from the view that it is “the most wonderful thing in the world” and understand it as an “iatrogenic” institution, which means it makes people sick.

Ouch. What will it cost to recapitalize the thing? How long will it take? I am more optimistic about England than most commentators these days, but this is perhaps problem number one?

To be clear, I nonetheless recognize the recent successes of the NHS in collecting data and testing hypotheses. It is patient care at the retail level that is the problem.

Is it Possible to Prepare for a Pandemic?

In a new paper, Robert Tucker Omberg and I ask whether being “prepared for a pandemic” ameliorated or shortened the pandemic. The short answer is No.

How effective were investments in pandemic preparation? We use a comprehensive and detailed measure of pandemic preparedness, the Global Health Security (GHS) Index produced by the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security (JHU), to measure which investments in pandemic preparedness reduced infections, deaths, excess deaths, or otherwise ameliorated or shortened the pandemic. We also look at whether values or attitudinal factors such as individualism, willingness to sacrifice, or trust in government—which might be considered a form of cultural pandemic preparedness—influenced the course of the pandemic. Our primary finding is that almost no form of pandemic preparedness helped to ameliorate or shorten the pandemic. Compared to other countries, the United States did not perform poorly because of cultural values such as individualism, collectivism, selfishness, or lack of trust. General state capacity, as opposed to specific pandemic investments, is one of the few factors which appears to improve pandemic performance. Understanding the most effective forms of pandemic preparedness can help guide future investments. Our results may also suggest that either we aren’t measuring what is important or that pandemic preparedness is a global public good.

Our results can be simply illustrated by looking at daily Covid deaths per million in the country the GHS Index ranked as the most prepared for a pandemic, the United States, versus the country the GHS Index ranked as least prepared, Equatorial Guinea.

Now, of course, this is just raw data–maybe the US had different demographics, maybe Equatorial Guinea underestimated Covid deaths, maybe the GHS index is too broad or maybe sub-indexes measured preparation better. The bulk of our paper shows that the lesson of Figure 1 continue to apply even after controlling for a variety of demographic factors, when looking at other measures of deaths such as excess deaths, when looking at the time pattern of deaths etc. Note also that we are testing whether “preparedness” mattered and finding that it wasn’t an important factor in the course of the pandemic. We are not testing and not arguing that pandemic policy didn’t matter.

The lessons are not entirely negative, however. The GHS index measures pandemic preparedness by country but what mattered most to the world was the production of vaccines which depended less on any given country and more on global preparedness. Investing in global public goods such as by creating a library of vaccine candidates in advance that we could draw upon in the event of a pandemic is likely to have very high value. Indeed, it’s possible to begin to test and advance to phase I and phase II trials vaccines for every virus that is likely to jump from animal to human populations (Krammer, 2020). I am also a big proponent of wastewater surveillance. Every major sewage plant in the world and many minor plants at places like universities ought to be doing wastewater surveillance for viruses and bacteria. The CDC has a good program along these lines. These types of investments are global public goods and so don’t show up much in pandemic preparedness indexes, but they are key to a) making vaccines available more quickly and b) identifying and stopping a pandemic quickly.

A final lesson may be that a pandemic is simply one example of a low-probability but very bad event. Other examples which may have even greater expected cost are super-volcanoes, asteroid strikes, nuclear wars, and solar storms (Ord, 2020; Leigh, 2021). Preparing for X, Y, or Z may be less valuable than building resilience for a wide variety of potential events. The Boy Scout motto is simply ‘Be prepared’.

Read the whole thing.

The decline of religion, and the rise of deaths of despair

In recent decades, death rates from poisonings, suicides, and alcoholic liver disease have dramatically increased in the United States. We show that these “deaths of despair” began to increase relative to trend in the early 1990s, that this increase was preceded by a decline in religious participation, and that both trends were driven by middle-aged white Americans. Using repeals of blue laws as a shock to religiosity, we confirm that religious practice has significant effects on these mortality rates. Our findings show that social factors such as organized religion can play an important role in understanding deaths of despair.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Tyler Giles, Daniel M. Hungerman, and Tamar Oostrom. Ross Douthat, telephone!

Testing Freedom

In the latest Discourse Magazine I discuss the FDA’s long-standing fear and antipathy toward personalized medical tests and how this violates the 1st Amendment.

In 1972, the FDA confiscated thousands of home pregnancy tests, declaring that they were “drugs” meant to diagnose a “disease” and thus fell under the FDA’s regulatory dominion. The case went to the U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey, and Judge Vincent P. Biunno ruled that the FDA had overstepped. “Pregnancy,” he said, “is a normal physiological function of all mammals and cannot be considered a disease … a test for pregnancy, then, is not a test for the diagnosis of disease. It is no more than a test for news….” As a result of Judge Biunno’s ruling, home pregnancy tests are easily available today from pharmacies, grocery stores and online shops without a prescription.

These days, debates over home pregnancy tests from the 1970s seem anachronistic and paternalistic. Yet the same paternalistic arguments appear again and again with every new testing technology. In the late 1980s, for example, the FDA simply declared that it would not approve at-home HIV tests, regardless of their safety or efficacy. As with pregnancy tests, the concern was that people could not be trusted with information about their own bodies…the first rapid at-home HIV test was developed and submitted to the FDA in 1987 [but] it took 25 years before the FDA would approve these tests. (Now, you can easily buy such a test on Amazon.)

…The FDA has a vital role in ensuring that tests are clinically accurate—tests should do what they say they do. Tests don’t need to be perfectly accurate to be useful (think of thermometers, personality tests and tire pressure gauges), but if a test advertises that it measures HDL cholesterol, it should do that within the tolerances the firm promises. The FDA has the technical knowledge to ensure that tests work, and that’s a skill that Americans value from the agency.

What Americans don’t want is to be told they can’t handle the truth. Yet when it came to at-home tests such as pregnancy tests, HIV tests and genetic tests, that’s exactly the reasoning the FDA used—and continues to use—to suppress information. The FDA should ensure that tests are safe, but “safety” means physical safety. The FDA may not declare a product unsafe because it might produce dangerous knowledge. Patients have a right to know about their own bodies. Our antibodies, ourselves. The FDA has authority over drugs and devices but not over patients.

Judge Biunno had it right back in 1972 when he said that diagnostic tests produce “news.” Test results, therefore, are a type of speech that fall under the First Amendment right to freedom of speech. The Supreme Court has repeatedly rejected restrictions on freedom of speech based on “a fear that people would make bad decisions if given truthful information”; thus, FDA restrictions on tests based on such fears are unconstitutional. The question of whether consumers will respond “safely” to test results is no more relevant to the FDA’s regulatory authority than the question of whether readers will respond safely to political news published in The New York Times. The FDA does not have the constitutional authority to regulate news.

How much did pre-ACA Medicaid expansions matter?

This paper examines the impact of Medicaid expansions to parents and childless adults on adult mortality. Specifically, we evaluate the long-run effects of eight state Medicaid expansions from 1994 through 2005 on all-cause, healthcare-amenable, non-healthcare-amenable, and HIV-related mortality rates using state-level data. We utilize the synthetic control method to estimate effects for each treated state separately and the generalized synthetic control method to estimate average effects across all treated states. Using a 5% significance level, we find no evidence that Medicaid expansions affect any of the outcomes in any of the treated states or all of them combined. Moreover, there is no clear pattern in the signs of the estimated treatment effects. These findings imply that evidence that pre-ACA Medicaid expansions to adults saved lives is not as clear as previously suggested.

That is a new NBER working paper from Charles J. Courtemanche, Jordan W. Jones, Antonios M. Koumpias, and Daniela Zapata.

Here are some relevant pictures. Now, would you expect subsequent Medicaid expansions to have higher, lower, or the same marginal value?

David Wallace-Wells on the pandemic

Rather than quote the parts where he says nice things about Alex and me, how about a wee excerpt on the GBD crowd:

Dr. Bhattacharya, for instance, proclaimed in The Wall Street Journal in March 2020 that Covid-19 was only one-tenth as deadly as the flu. In January 2021 he wrote an opinion essay for the Indian publication The Print suggesting that the majority of the country had acquired natural immunity from infection already and warning that a mass vaccination program would do more harm than good for people already infected. Shortly thereafter, the country’s brutal Delta wave killed perhaps several million Indians. In May 2020, Dr. Gupta suggested that the virus might kill around five in 10,000 people it infected, when the true figure in a naïve population was about one in 100 or 200, and that Covid was “on its way out” in Britain. At that point, it had killed about 45,000 Britons, and it would go on to kill about 170,000 more. The following year, Dr. Bhattacharya and Dr. Kulldorff together made the same point about the disease in the United States — that the pandemic was “on its way out” — on a day when the American death toll was approaching 600,000. Today it is 1.1 million and growing.

It has fallen down the memory hole a bit just how um…”off” these people were, and that is the polite word. That said, I don’t think they should have been banned from any social media platforms. Here is the full NYT piece, excellent throughout, and mostly about other topics. For the pointer I thank Alex T.

Shruti Rajagopalan and Janhavi Nilekani podcast

In this episode, Shruti speaks with [the excellent] Janhavi Nilekani about India’s high rate of C-sections compared with vaginal births, problems with maternal healthcare, the present and future of Indian midwifery and much more. Nilekani is the founder and chair of the Aastrika Foundation, which seeks to promote a future in which every woman is treated with respect and dignity during childbirth, and the right treatment is provided at the right time. She is a development economist by training and now works in the field of maternal health. She obtained her Ph.D. in public policy from Harvard and holds a 2010 B.A., cum laude, in economics and international studies from Yale.

Here is the link.

Retrospective look at rapid Covid testing

To be clear, I still favor rapid Covid tests, and I believe we were intolerably slow to get these underway. The benefits far exceed the costs, and did earlier on in the pandemic as well.

That said, with a number of pandemic retrospectives underway, here is part of mine. I don’t think the strong case for those tests came close to panning out.

I had raised some initial doubts in my podcasts with Paul Romer and also with Glen Weyl, mostly about the risk of an inadequate demand to take such tests. I believe that such doubts have been validated.

Ideally what you want asymptomatic people in high-risk positions taking the tests on a frequent basis, and, if they become Covid-positive, learning they are infectious before symptoms set in (remember when the FDA basically shut down Curative for giving tests to the asymptomatic? Criminal). And then isolating themselves. We had some of that. But far more often I witnessed:

1. People with symptoms taking the tests to confirm they had Covid. Nothing wrong with that, but it leads to a minimal gain, since in so many cases it was pretty clear without the test.

2. Various institutions requiring tests for meet-ups and the like. These tests would catch some but not all cases, and the event still would turn into a spreader event, albeit at a probably lower level than otherwise would have been the case.

3. Nervous Nellies taking the test in low-risk situations mainly to reassure themselves and others. Again, no problems there but not the highest value use either.

So the prospects for mass rapid testing — done in the most efficacious manner — were I think overrated.

I recall the summer of 2022 in Ireland, which by the way is when I caught Covid (I was fine, though decided to spend an extra week in Ireland rather than risk infecting my plane mates). Rapid tests were available everywhere, and at much lower prices than in the United States. Better than not! But what really seemed to make the difference was vaccines. The availability of all those tests did not do so much to prevent Covid from spreading like a wildfire during that Irish summer. Fortunately, deaths rose but did not skyrocket.

The well-known Society for Healthcare Epidemiology just recommended that hospitals stop testing asymptomatic patients for Covid. You may or may not agree, but that is a sign of how much status testing has lost.

Some commentators argue there are more false negatives on the rapid tests with Omicron than with earlier strains. I haven’t seen proof of this claim, but it is itself noteworthy that we still are not sure how good the tests are currently. That too reflects a lower status for testing.

Again, on a cost-benefit basis I’m all for such testing! But I’ve been lowering my estimate of its efficacy.

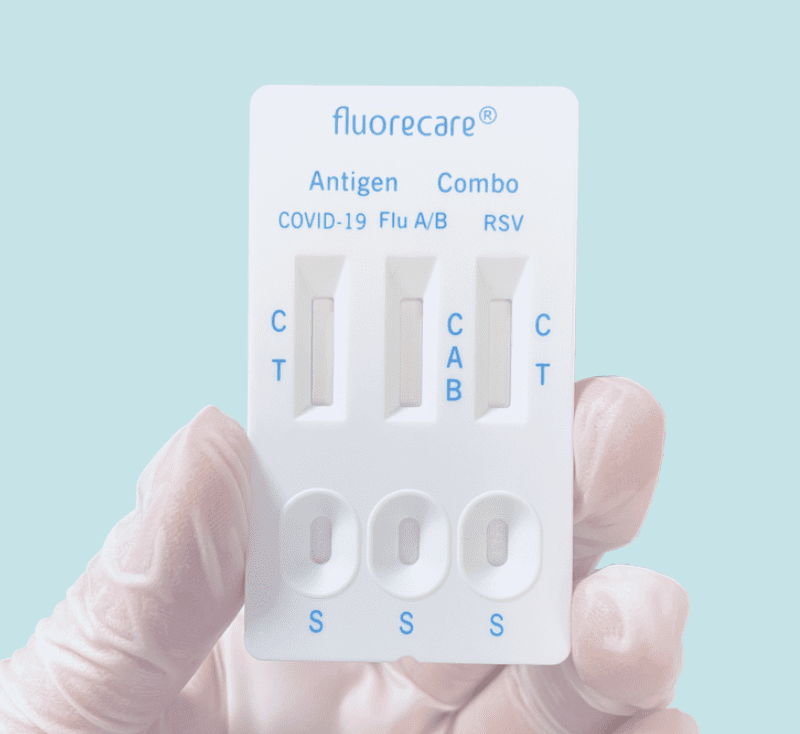

Combination Rapid Tests

Once again, the US is behind on at-home rapid antigen tests–this time on combination tests that let you test for COVID, Influenza, and RSV all at once. These tests are widely available in Europe but have not been approved by the FDA. Rapid flu tests especially are potentially very useful in assigning appropriate treatment and reducing the overuse of antibiotics.

Does reducing lead exposure limit crime?

These results seem a bit underwhelming, and furthermore there seems to be publication bias, this is all from a recent meta-study on lead and crime. Here goes:

Does lead pollution increase crime? We perform the first meta-analysis of the effect of lead on crime by pooling 529 estimates from 24 studies. We find evidence of publication bias across a range of tests. This publication bias means that the effect of lead is overstated in the literature. We perform over 1 million meta-regression specifications, controlling for this bias, and conditioning on observable between-study heterogeneity. When we restrict our analysis to only high-quality studies that address endogeneity the estimated mean effect size is close to zero. When we use the full sample, the mean effect size is a partial correlation coefficient of 0.11, over ten times larger than the high-quality sample. We calculate a plausible elasticity range of 0.22-0.02 for the full sample and 0.03-0.00 for the high-quality sample. Back-ofenvelope calculations suggest that the fall in lead over recent decades is responsible for between 36%-0% of the fall in homicide in the US. Our results suggest lead does not explain the majority of the large fall in crime observed in some countries, and additional explanations are needed.

Here is one image from the paper:

The authors on the paper are Anthony Higney, Nick Hanley, and Mirko Moroa. I have long been agnostic about the lead-crime hypothesis, simply because I never had the time to look into it, rather than for any particular substantive reason. (I suppose I did have some worries that the time series and cross-national estimates seemed strongly at variance.) I can report that my belief in it is weakening…

Why did China do such a flip-flop on Covid?

After the so-called “Zero Covid” experiment, China now reports that 37 million people are being infected each day. What ever happened to the Golden Mean? Why not move smoothly along a curve? Even after three years’ time, it seems they did little to prep their hospitals. What are some hypotheses for this sudden leap from one corner of the distribution to the other?

1. The Chinese people already were so scared of Covid, the extreme “no big deal” message was needed to bring them around to a sensible middle point. After all, plenty of parts of China still are seeing voluntary social distancing.

2. For Chinese social order, “agreement” is more important than “agreement on what.” And agreement is easiest to reach on extreme, easily stated and explained policies. Zero Covid is one such policy, “let it rip” is another. In the interests of social stability China, having realized its first extreme message was no longer tenable, has decided to move to the other available simple, extreme message. And so they are letting it rip.

3. The Chinese elite ceased to believe in the Zero Covid policy even before the protests spread to such an extreme. But it was not possible to make advance preparations for any alternative policy. Thus when Zero Covid fell away, there was a vacuum of sorts and that meant a very loose policy of “let it rip.”

4. After three years of Zero Covid hardship, the Chinese leadership feels the need to “get the whole thing over with” as quickly as possible.

To which extent might any of these be true? What else?

The economic costs of depression amongst the young

A growing body of evidence indicates that poor health early in life can leave lasting scars on adult health and economic outcomes. While much of this literature focuses on childhood experiences, mechanisms generating these lasting effects – recurrence of illness and interruption of human capital accumulation – are not limited to childhood. In this study, we examine how an episode of depression experienced in early adulthood affects subsequent labor market outcomes. We find that, at age 50, people who had met diagnostic criteria for depression when surveyed at ages 27-35 earn 10% lower hourly wages (conditional on occupation) and work 120-180 fewer hours annually, together generating 24% lower annual wage incomes. A portion of this income penalty (21-39%) occurs because depression is often a chronic condition, recurring later in life. But a substantial share (25-55%) occurs because depression in early adulthood disrupts human capital accumulation, by reducing work experience and by influencing selection into occupations with skill distributions that offer lower potential for wage growth. These lingering effects of early depression reinforce the importance of early and multifaceted intervention to address depression and its follow-on effects in the workplace.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Buyi Wang, Richard G. Frank, and Sherry A. Glied.

The FDA’s Lab-Test Power Grab

The FDA is trying to gain authority over laboratory developed tests (LDTs). It’s a bad idea. Writing in the WSJ, Brian Harrison, who served as chief of staff at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019-2021 and Bob Charrow, who served as HHS general counsel, 2018-2021, write:

We both were involved in preparing the federal Covid-19 public-health emergency declaration. When it was signed on Jan. 31, 2020, the intent was to cut red tape and maximize regulatory flexibility to allow a nimble response to an emerging pandemic.

Unknown to us, the next day the FDA went in the opposite direction: It issued a new requirement that labs stop testing for Covid-19 and first apply for FDA authorization. At that time, LDTs were the only Covid tests the U.S. had, and many were available and ready to be used in labs around the country. But since the process for emergency-use authorization was extremely burdensome and slow—and because, as we and others in department leadership learned, it couldn’t process applications quickly—many labs stopped trying to win authorization, and some pleaded for regulatory relief so they could test.

Through this new requirement the FDA effectively outlawed all Covid-19 testing for the first month of the pandemic when detection was most critical. One test got through—the one developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—but it proved to be one of the highest-profile testing failures in history because the entire nation was relying on the test to work as designed, and it didn’t.

When we became aware of the FDA’s action, one of us (Mr. Harrison) demanded an immediate review of the agency’s legal authority to regulate these tests, and the other (Mr. Charrow) conducted the review. Based on the assessment, a determination was made by department leadership that the FDA shouldn’t be regulating LDTs.

Congress has never expressly given the FDA authority to regulate the tests. Further, in 1992 the secretary of health and human services issued a regulation stating that these tests fell under the jurisdiction of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, not the FDA. Bureaucrats at the FDA have tried to ignore this rule even though the Supreme Court in Berkovitz v. U.S. (1988) specifically admonished the agency for ignoring federal regulations.

Loyal readers will recall that I covered this issue earlier in Clement and Tribe Predicted the FDA Catastrophe. Clement, the former US Solicitor General under George W. Bush and Tribe, a leading liberal constitutional lawyer, rejected the FDA claims of regulatory authority over laboratory developed tests on historical, statutory, and legal grounds but they also argued that letting the FDA regulate laboratory tests was a dangerous idea. In a remarkably prescient passage, Clement and Tribe (2015, p. 18) warned:

The FDA approval process is protracted and not designed for the rapid clearance of tests. Many clinical laboratories track world trends regarding infectious diseases ranging from SARS to H1N1 and Avian Influenza. In these fast-moving, life-or-death situations, awaiting the development of manufactured test kits and the completion of FDA’s clearance procedures could entail potentially catastrophic delays, with disastrous consequences for patient care.

Clement and Tribe nailed it. Catastrophic delays, with disastrous consequences for patient care is exactly what happened. Thus, Harrison and Charrow are correct, giving the FDA power over laboratory derived tests has had and will have significant costs.