Category: Medicine

Update on the Supervillains (maybe that’s you)

The law’s price controls will also deter companies from developing new medicines. A study I co-authored estimated that 135 fewer drugs will come to market through 2039 because of the Inflation Reduction Act. Research firm Vital Transformation’s forecast is even bleaker, predicting that the U.S. could lose 139 drugs within the next decade.

Dozens of life-sciences companies have announced cuts to their research and development pipelines because of the 2022 law. These announcements have come in earnings calls and filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission—where deliberate misstatements would expose executives to civil and criminal penalties—so they can’t be chalked up to political posturing.

That is from Tomas Philipson at the WSJ. It is worth noting this kind of academic research has not been effectively rebutted, rather what you usually hear in response is a bunch of snarky comments about Big Pharma and the like.

And to repeat myself yet again: if you are ever tempted to cancel somebody, ask yourself “do I cancel those who favor tougher price controls on pharma? After all, they may be inducing millions of premature deaths.” If you don’t cancel those people — and you shouldn’t — that should broaden your circle of tolerance more generally.

Testing for Bird Flu is Too Slow

Remember my warnings about the FDAs takeover of lab developed tests?

…Lab developed tests have never been FDA regulated except briefly during the pandemic emergency when such regulation led to catastrophic consequences. Catastrophic consequences that had been predicted in advanced by Paul Clement and Lawrence Tribe. Despite this, for reasons I do not understand, the FDA plan is marching forward but many other people are starting to warn of dire consequences.

Well the plan marched forward and here we are. Regarding tests for bird flu:

KFFNews: Clinical laboratories have also begun to develop their own tests from scratch. But researchers said they’re moving cautiously because of a recent FDA rule that gives the agency more oversight of lab-developed tests, lengthening the pathway to approval. In an email to KFF Health News, FDA press officer Janell Goodwin said the rule’s enforcement will occur gradually.

However, Susan Van Meter, president of the American Clinical Laboratory Association, a trade group whose members include the nation’s largest commercial diagnostic labs, said companies need more clarity: “It’s slowing things down because it’s adding to the confusion about what is allowable.”

One of the motivations for Operation Warp Speed and my work during the pandemic on things like advance market commitments was that firms wouldn’t invest enough in tests because diseases might fizzle out. The extreme costs of shutting down the economy, however, mean that it’s well worth paying for some tests for diseases that fizzle out if tests are ready when a disease doesn’t fizzle out.

Creating tests for the bird flu is already a risky bet, because demand is uncertain. It’s not clear whether this outbreak in cattle will trigger an epidemic or fizzle out. In addition to issues with the CDC and FDA, clinical laboratories are trying to figure out whether health insurers or the government will pay for bird flu tests.

We need a pandemic trust fund to ramp up advance market commitments when necessary.

On the plus side, I do approve of the new program to pay farmers and farm workers for testing. For example:

Friday’s incentives announcement included a $75 payment to any farm worker who agrees to give blood and nasal swab samples to the CDC.

“Bird flu” has now infected more than 50 types of mammals. To be clear, bird flu may yet fade but every potential pandemic pathogen is a test of readiness and we still are getting a C+ at best.

The Pentagon’s Anti-Vax Campaign

During the pandemic it was common for many Americans to discount or even disparage the Chinese vaccines. In fact, the Chinese vaccines such as Coronavac/Sinovac were made quickly and in large quantities and they were effective. The Chinese vaccines saved millions of lives. The vaccine portfolio model that the AHT team produced, as well as common sense, suggested the value of having a diversified portfolio. That’s why we recommended and I advocated for including a deactivated vaccine in the Operation Warp Speed mix or barring that for making an advance deal on vaccine capacity with China. At the time, I assumed that the disparaging of Chinese vaccines was simply an issue of national pride or bravado during a time of fear. But it turns out that in other countries, the Pentagon ran a disinformation campaign against the Chinese vaccines.

Reuters: At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. military launched a secret campaign to counter what it perceived as China’s growing influence in the Philippines, a nation hit especially hard by the deadly virus.

The clandestine operation has not been previously reported. It aimed to sow doubt about the safety and efficacy of vaccines and other life-saving aid that was being supplied by China, a Reuters investigation found. Through phony internet accounts meant to impersonate Filipinos, the military’s propaganda efforts morphed into an anti-vax campaign.

… Tailoring the propaganda campaign to local audiences across Central Asia and the Middle East, the Pentagon used a combination of fake social media accounts on multiple platforms to spread fear of China’s vaccines among Muslims at a time when the virus was killing tens of thousands of people each day. A key part of the strategy: amplify the disputed contention that, because vaccines sometimes contain pork gelatin, China’s shots could be considered forbidden under Islamic law.

…To implement the anti-vax campaign, the Defense Department overrode strong objections from top U.S. diplomats in Southeast Asia at the time, Reuters found. Sources involved in its planning and execution say the Pentagon, which ran the program through the military’s psychological operations center in Tampa, Florida, disregarded the collateral impact that such propaganda may have on innocent Filipinos.

“We weren’t looking at this from a public health perspective,” said a senior military officer involved in the program. “We were looking at how we could drag China through the mud.”

Frankly, this is sickening. The Pentagon’s anti-vax campaign has undermined U.S. credibility on the global stage and eroded trust in American institutions, and it will complicate future public health efforts. US intelligence agencies should be banned from interfering with or using public health as a front.

Moreover, there was a better model. It’s often forgotten but the elimination of smallpox from the planet, one of humanities greatest feats, was a global effort spearheaded by the United States and….the Soviet Union.

…even while engaged in a pitched battle for influence across the globe, the Soviet Union and the United States were able to harness their domestic and geopolitical self-interests and their mutual interest in using science and technology to advance human development and produce a remarkable public health achievement.

We could have taken a similar approach with China during the COVID pandemic.

More generally, we face global challenges, from pandemics to climate change to artificial intelligence. Addressing these challenges will require strategic international cooperation. This isn’t about idealism; it’s about escaping the prisoner’s dilemma. We can’t let small groups with narrow agendas and parochial visions undermine collaborations essential for our interests and security in an interconnected world.

Enhancing FDA Information Sharing for Neglected Tropical Diseases

Many countries look to the US FDA for guidance on approval decisions. In fact the FDA will sometimes receive and evaluate drugs and vaccines whose primary market is in less developed countries. Fexinidazole, for example, is a drug for treating African trypanosomiasis, i.e. sleeping sickness. We don’t get many cases of sleeping sickness in the US but there are many such cases in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Thus, the US FDA is providing a useful service, both to US pharmaceutical firms and especially to developing countries. That’s great. But Jacob Trefethen of OpenPhil notes that for odd bureaucratic and legal reasons we redact a lot of information that could be useful to the countries that actually will use these treatments. Here, for example, is an excerpt from the approval decision for Fexinidazole:

What’s especially strange here is that as far as Trefethen, or I, can tell, no one wants this! The FDA has no reason to hide this information, the company submitting the proposal surely wants as much information as possible sent to the countries where they will ultimately need to get approval (remember this is successful applications!) and the medical agencies in the developing countries would like to get context to have confidence in the FDA’s decisions. Instead, it seems that these drugs are getting caught in rules intended to protect pharmaceutical firms in other contexts. Thus, Trefethen makes two suggestions:

let’s create a track for products on the Neglected Tropical Disease list, sharing assessments with few or no redactions with the WHO Pre-Qualification (PQ) system, and allow PQ to share those documents further with regulators in partner countries.

Such an approval track already exists in the EU:

[The EU] have an approval track for products that are mostly going to be used elsewhere. If you apply using that track, they loop in regulators from those countries too. They share the documents assessing your clinical data and inspecting your manufacturing site with the WHO prequalification (PQ) team – the team whose stamp of approval speeds things up for many countries with less experienced national regulators. Gavi and the Global Fund need a product to be prequalified in order to buy it through the UN procurement agencies (e.g. UNICEF, for children’s vaccines).

Even without an approval track there are other small changes in priority and emphasis that could improve information sharing. The FDA is not unaware of these information sharing issues, for example, and there are procedures in place for confidentiality agreements with other countries. Trefethen suggests these could be given greater priority.

FDA leadership should set aggressive goals to complete more two-way Confidentiality Commitments with lower- and middle-income country regulators.

Extend the scope of existing commitments, when they’re limited, to allow sharing in more areas – especially related to drug approvals.

Extend 708(c) authority to more country agreements, not just those with European countries, to allow sharing of full documents that include trade secrets.

I’ve long advocated for peer approval, Trefethen gets into the weeds to point to specific ideas to make this a more useful idea, especially for developing countries. See Trefethen for more ideas!

Fauci Didn’t Test

I am not a Fauci hater but I think this criticism of Facui from epidemiologist and oncologist Vinay Prasad hits the mark:

Lockdown was specifically advocated for by Anthony Fauci (‘15 days to stop the spread’/ ‘hunker down’/ ‘shelter in place’), and Fauci would go on to make hundreds of other specific policy recommendations. Although he initially rejected it, by April 2020, he recommended community cloth masking to slow the coronavirus (an intervention for which we now have randomized data showing it doesn’t work).

Fauci opposed Ron DeSantis in numerous TV interviews in spring 2020 when DeSantis reopened schools. He called school reopening reckless— though it was widely embraced in western Europe at the time, and now clearly the correct policy choice.

Fauci supported vaccine mandates and border closure. He repeated the false statement that 6ft of social distancing had an empirical basis. Many in the media and medicine think criticizing him is unfair— he did the best he could with what he knew at the time—but it is fair to criticize a scientist who presented his views as facts when they were at best speculation. And, moreover, there is one criticism that no one can deny:

Although he was director of the NIAID, and although he controlled a 5 billion dollar infectious disease research budget, he chose to launch, fund and conduct precisely ZERO randomized trials of non-pharmacologic interventions.

Hat tip: MD.

The Marginal Revolution Theory of Innovation

A FDA panel voted against approving MDMA (ecstasy) for post-traumatic stress disorder. Putting aside the specifics of the case, I was vexed by this statement on innovation from one of the experts voting no:

“I absolutely agree that we need new and better treatments for PTSD,” said Paul Holtzheimer, deputy director for research at the National Center for PTSD, a panelist who voted no on the question of whether the benefits of MDMA-therapy outweighed the risks.

“However, I also note that premature introduction of a treatment can actually stifle development, stifle implementation and lead to premature adoption of treatments that are either not completely known to be safe, not fully effective or not being used at their optimal efficacy,” he added.

A textbook example of making the perfect the enemy of the good. But the problem is even worse. Holtzheimer seems to think that treatments spring from the lab perfectly formed like Athena springing from the brow of Zeus. Indeed, Holtzheimer suggests that treatments should be kept in the lab until they are perfect. News flash: there are no perfect treatments–no drug or device in use today is completely known to be safe, fully effective, and used at its optimal efficacy. Not one. If we follow Holtzheimer’s counsel, we will never approve a new drug.

Innovation is a dynamic process; success rarely comes on the first attempt. The key to innovation is continuous refinement and improvement. A firm with sales gains greater resources to invest in further research and development. Additionally, they benefit from customer feedback, which provides valuable insights for enhancing their products and processes. Learning by doing requires doing. But if imperfect treatments are never approved, scientists often don’t return to the lab to refine and improve them. Instead, the project dies. Thus, when considering innovation today, it’s essential to think about not only the current state of technology but also about the entire trajectory of development. A treatment that’s marginally better today may be much better tomorrow.

Small steps toward a much better world.

The NIH Doesn’t Fund Small Crappy Trials

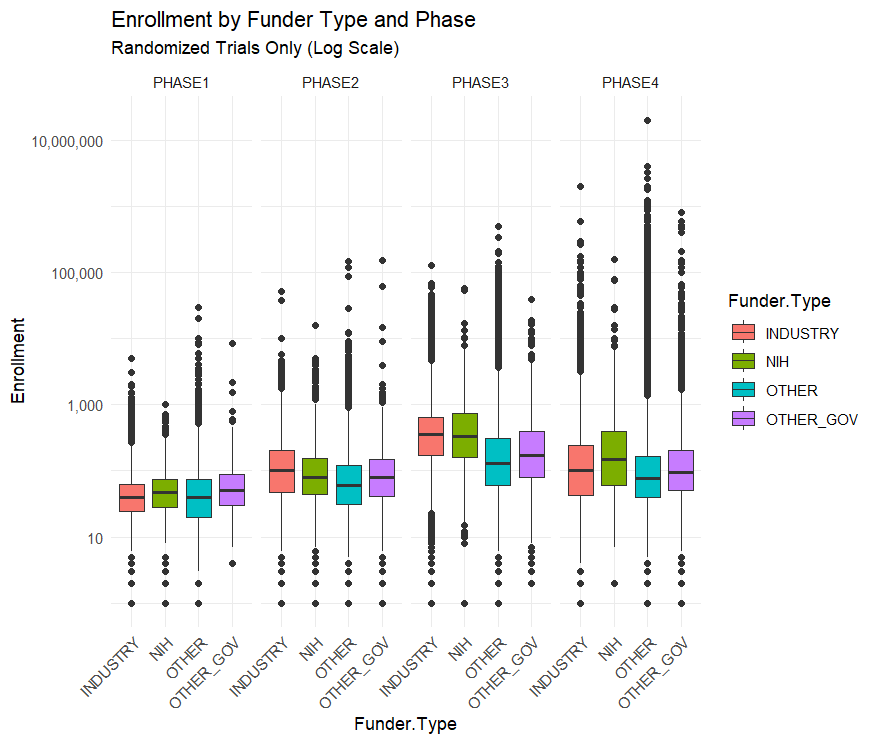

A nice catch by Max at Maximum Progress:

[A common critique] is that the NIH funds too many “small crappy trials.” That quote is from a FDA higher up, but the story has been repeated by many others…I downloaded all of the clinical trial data from ClinicalTrials.gov to find out….The median NIH funded trial has 48 participants while the median industry funded trial has 67. The average NIH funded trial has 288 participants while the average industry trial has 335 and the average “Other” funded trial (mostly universities and the associated hospitals) has 923 participants.

By median or by average NIH trials are the smallest out of all the funders. This seems to confirm the “small crappy trials” narrative

…This narrative is reversed, however, when you split up the trials by phase.

Across all trials NIH funded ones are the smallest, but within each phase NIH trials are the largest or second largest. Their overall small enrollment average is just due to the fact that they fund more Phase I trials than Phase III. But NIH Phase I trials have a bigger sample size than industry funded trials on average.

This is an example of Simpson’s Paradox in the wild!

Arguing that the NIH should stop funding unusually small trials is easy but arguing that they should shift from funding the Phase I trials closest to basic research towards later stage trials is less clear.

The NIH’s clinical trial strategy is certainly not perfect and improving it is valuable. But a systematic bias towards “small crappy trials” doesn’t really seem like it’s an important problem facing the NIH.

Two From the Tabarrok Brothers

Maxwell Tabarrok offers an excellent review of an important paper.

Taxation and Innovation in the 20th Century is a 2018 paper by Ufuk Akcigit, John Grigsby, Tom Nicholas, and Stefanie Stantcheva that provides some answers. They collect and clean new datasets on patenting, corporate and individual incomes, and state-level tax rates that extend back to the early 20th century. The headline result: taxes are a huge drag on innovation. A one percent increase in the marginal tax rate for 90th percentile income earners decreases the number of patents and inventors by 2%. The corporate tax rate is even more important, with a one percent increase causing 2.8% fewer patents and 2.3% fewer inventors.

Especially useful is Max’s back of the envelope calculation putting this result in the context of other methods to increases innovation.

Read the whole thing.

For something completely different, Connor Tabarrok offers an update on Charlotte the Stingray:

A “miracle pregnancy” picked up by national news brought huge business to a small-town aquarium, but months after the famous stingray was due, there are still no pups. Are we being scammed by a fish?

I particularly liked this line:

Taking all of this into account, my stance is that even if they got it on, it’s unlikely that this shark will have to dish out any child support to Charlotte’s pups.

Read the whole thing.

Are MR readers more interested in tax policy or virgin birth stingrays? We shall see.

Money for Blood and Short Term Jobs

The excellent Tim Taylor on a new paper on plasma donation:

John M Dooley and Emily A Gallagher take a different approach in “Blood Money: Selling Plasma to Avoid High-Interest Loans” (Review of Economic Studies, forthcoming, published online May2, 2024; SSRN working paper version here). They are investigating how the opening of a blood plasma center in an area affects the finances of low-income individuals. As background, they write:

“Plasma, a component of blood, is a key ingredient in medications that treat millions of people for immune disorders and other illnesses. At over $26 billion in annual value in 2021, plasma represents the largest market for human materials. The U.S. provides 70% of the global plasma supply, putting blood products consistently in the country’s top ten export categories. The U.S. produces this level of plasma because, unlike most other countries, the U.S. allows pharmaceutical corporations to compensate donors – typically about $50 per donation for new donors, with rates reaching $200 per donation during severe shortages. The U.S. also permits comparatively high donation frequencies: up to twice per week (or 104 times per year)…”

Not too surprisingly, plasma donors tend to be young and poor and they use plasma donation to substitute away from non-bank credit like payday loans.

I am struck by Tim’s thoughts on how this connects with labor markets and regulation:

…I find myself thinking about the financial stresses that many Americans face. Being paid a few hundred dollars for a series of plasma donations isn’t an ideal answer. Neither is taking out a high-interest short-term loan; indeed, taking out a loan at all may be a poor idea if you aren’t expecting to have the income to pay it back. In the modern US economy, hiring someone for even a short-term job involves human resources departments, paperwork, personal identification, bookkeeping, and tax records. These rules have their reasons, but the result is that finding a short-term job that pays for a few days work isn’t simple, even if though most urban areas have a semi-underground network of such jobs.

Roger Miller’s classic 1964 song, “King of the Road,” tells us that “two hours of pushin’ broom/ Buys an eight by twelve four-bit room.” Even after allowing for a certain romancing of the life of a hobo in that song, the notion that a low-income person can walk out the door and find an two-hour job that pays enough to solve immediate cash-flow problems–other than donating plasma–seems nearly impossible in the modern economy.

Deadly Precaution

MSNBC asked me to put together my thoughts on the FDA and sunscreen. I think the piece came out very well. Here are some key grafs:

…In the European Union, sunscreens are regulated as cosmetics, which means greater flexibility in approving active ingredients. In the U.S., sunscreens are regulated as drugs, which means getting new ingredients approved is an expensive and time-consuming process. Because they’re treated as cosmetics, European-made sunscreens can draw on a wider variety of ingredients that protect better and are also less oily, less chalky and last longer. Does the FDA’s lengthier and more demanding approval process mean U.S. sunscreens are safer than their European counterparts? Not at all. In fact, American sunscreens may be less safe.

Sunscreens protect by blocking ultraviolet rays from penetrating the skin. Ultraviolet B (UVB) rays, with their shorter wavelength, primarily affect the outer skin layer and are the main cause of sunburn. In contrast, ultraviolet A (UVA) rays have a longer wavelength, penetrate more deeply into the skin and contribute to wrinkling, aging and the development of melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer. In many ways, UVA rays are more dangerous than UVB rays because they are more insidious. UVB rays hit when the sun is bright, and because they burn they come with a natural warning. UVA rays, though, can pass through clouds and cause skin cancer without generating obvious skin damage.

The problem is that American sunscreens work better against UVB rays than against the more dangerous UVA rays. That is, they’re better at preventing sunburn than skin cancer. In fact, many U.S. sunscreens would fail European standards for UVA protection. Precisely because European sunscreens can draw on more ingredients, they can protect better against UVA rays. Thus, instead of being safer, U.S. sunscreens may be riskier.

Most op-eds on the sunscreen issue stop there but I like to put sunscreen delay into a larger context:

Dangerous precaution should be a familiar story. During the Covid pandemic, Europe approved rapid-antigen tests much more quickly than the U.S. did. As a result, the U.S. floundered for months while infected people unknowingly spread disease. By one careful estimate, over 100,000 lives could have been saved had rapid tests been available in the U.S. sooner.

I also discuss cough medicine in the op-ed and, of course, I propose a solution:

If a medical drug or device has been approved by another developed country, a country that the World Health Organization recognizes as a stringent regulatory authority, then it ought to be fast-tracked for approval in the U.S…Americans traveling in Europe do not hesitate to use European sunscreens, rapid tests or cough medicine, because they know the European Medicines Agency is a careful regulator, at least on par with the FDA. But if Americans in Europe don’t hesitate to use European-approved pharmaceuticals, then why are these same pharmaceuticals banned for Americans in America?

Peer approval is working in other regulatory fields. A German driver’s license, for example, is recognized as legitimate — i.e., there’s no need to take another driving test — in most U.S. states and vice versa. And the FDA does recognize some peers. When it comes to food regulation, for example, the FDA recognizes the Canadian Food Inspection Agency as a peer. Peer approval means that food imports from and exports to Canada can be sped through regulatory paperwork, bringing benefits to both Canadians and Americans.

In short, the FDA’s overly cautious approach on sunscreens is a lesson in how precaution can be dangerous. By adopting a peer-approval system, we can prevent deadly delays and provide Americans with better sunscreens, effective rapid tests and superior cold medicines. This approach, supported by both sides of the political aisle, can modernize our regulations and ensure that Americans have timely access to the best health products. It’s time to move forward and turn caution into action for the sake of public health and for less risky time in the sun.

The Left on FDA Peer Approval

Robert Kuttner discovered an excellent treatment for colds while vacationing in France and is rightly outraged that it’s not available in the United States:

Toward the end of our stay, my wife and I both got bad coughs (happily, not COVID). We went to our wonderful local pharmacist in search of something like Mucinex or Robitussin, which are not great but better than nothing.

“We have something much better,” said he. And he did. It’s called ambroxol. It works on an entirely different chemical principle, to thin sputum, facilitate productive coughing, and also operates as a pain reliever and gentle decongestant with no rebound effect.

We experienced it as a kind of miracle drug for coughs and colds. A box cost eight euros.

Ambroxol is available nearly everywhere in the world as a generic. It has been in wide use since 1979.

But not in the U.S.

…You can’t get ambroxol in the U.S. because of the failure of the Food and Drug Administration to grant reciprocal recognition to generic medications approved by its European counterpart, the European Medicines Agency, when they have long been proven safe and effective. To get FDA approval for the sale of ambroxol in the U.S., a drug company would need to sponsor extensive and costly clinical trials. Since it is a generic, as cheap as aspirin, no drug company would bother.

…I’ve petitioned the FDA, asking them to create a fast-track procedure, whereby generic drugs approved in Europe, and well established as safe and effective, could get reciprocal approval in the U.S.

This would produce approval of ambroxol as over-the-counter medication for coughs and colds without unnecessary new clinical trials. And should ambroxol turn out to have real benefits for Parkinson’s as well, it would already be well established in the U.S. as an inexpensive generic.

Influenced by my work on FDA reciprocity aka peer approval, Ted Cruz introduced a bill, the Result Act to fast-track approval in the United States for drugs and devices already approved in other developed countries. Similarly, AOC has noted that the FDA is far behind the world in approving advanced sunscreens. Perhaps there is an opportunity here for bipartisan support.

Hat tip: the excellent Scott Lincicome.

The willingness to pay for IVF

WHO estimates that as many as 1 in 6 individuals of reproductive age worldwide are affected by infertility. This paper uses rich administrative population-wide data from Sweden to construct and characterize the universe of infertility treatments, and to then quantify the private costs of infertility, the willingness to pay for infertility treatments, as well as the role of insurance coverage in alleviating infertility. Persistent infertility causes a long-run deterioration of mental health and couple stability, with no long-run “protective” effects (of having no child) on earnings. Despite the high private non-pecuniary cost of infertility, we estimate a relatively low revealed private willingness to pay for infertility treatment. The rate of IVF initiations drops by half when treatment is not covered by health insurance. The response to insurance is substantially more pronounced at lower income levels. At the median of the disposable income distribution, our estimates imply a willingness to pay of at most 22% of annual income for initiating an IVF treatment (or about a 30% chance of having a child). At least 40% of the response to insurance coverage can be explained by a liquidity effect rather than traditional moral hazard, implying that insurance provides an important consumption smoothing benefit in this context. We show that insurance coverage of infertility treatments determines both the total number of additional children and their allocation across the socioeconomic spectrum.

That is from a recent NBER working paper by Sarah Bögl, Jasmin Moshfegh, Petra Persson, and Maria Polyakova.

When are mental health interventions counterproductive?

The researchers point to unexpected results in trials of school-based mental health interventions in the United Kingdom and Australia: Students who underwent training in the basics of mindfulness, cognitive behavioral therapy and dialectical behavior therapy did not emerge healthier than peers who did not participate, and some were worse off, at least for a while.

And new research from the United States shows that among young people, “self-labeling” as having depression or anxiety is associated with poor coping skills, like avoidance or rumination.

In a paper published last year, two research psychologists at the University of Oxford, Lucy Foulkes and Jack Andrews, coined the term “prevalence inflation” — driven by the reporting of mild or transient symptoms as mental health disorders — and suggested that awareness campaigns were contributing to it.

“It’s creating this message that teenagers are vulnerable, they’re likely to have problems, and the solution is to outsource them to a professional,” said Dr. Foulkes, a Prudence Trust Research Fellow in Oxford’s department of experimental psychology, who has written two books on mental health and adolescence.

Here is more from Ellen Barry at the NYT.

Mask Mandate Costs

There is now an NBER working paper on this topic:

This paper presents the results from a hypothetical set of questions related to mask-wearing behavior and opinions that were asked of a nationally representative sample of over 4,000 participants in early 2022. Mask mandates were hotly debated in public discourse, and though much research exists on benefits of masks, there has been no research thus far on the distribution of perceived costs of compliance. As is common in economic research that aims to assess the value to society of non-market activities, we use survey valuation methods and ask how much participants would be willing to pay to be exempted from rules of mandatory community masking. The survey asks specifically about a 3 month exemption. We find that the majority of respondents (56%) are not willing to pay to be exempted from mandatory masking. However, the average person was willing to pay $525, and a small segment of the population (0.9%) stated they were willing to pay over $5,000 to be exempted from the mandate. Younger respondents stated higher willingness to pay to avoid the mandate than older respondents. Combining our results with standard measures of the value of a statistical life, we estimate that a 3 month masking order was perceived as cost effective through willingness-to-pay questions only if at least 13,333 lives were saved by the policy.

That is by Patrick Carlin, Shyam Raman, Kosali I. Simon, Ryan Sullivan, and Coady Wing. A few comments:

1. Willingness to be paid magnitudes are often much higher than willingness to pay numbers. Especially when issues of justice and desert are involved. I know some people who might say: “I have a right to refuse a mask. I’m not going to pay anything not to wear one, but you would have to pay me a million dollars to put it on.” There are less extreme versions of this view, noting that even in quite normal laboratory circumstances WTBP can be 5x higher than WTP.

2. For many people the value of masking — either positively or negatively — depends on what others do. Some might feel “I guess I can wear a mask, but if you make everyone do that, that is a gross Orwellian dystopia.” Others, perhaps leaning more to the political left, might say: “I am willing to do my share, but of course I expect the same from everyone else. Let us sing this collective song and with our masks dance to the heavens!”

3. Why not just look at what private sector establishments chose when the force of law was not present? Don’t they have the best sense of how to internalize all the different factors behind what their customers want? Of course the answer here will vary, depending on what stage of the pandemic we are in.

Culture splat (a few broad spoilers)

Challengers is a good and original movie. Imagine a 2024 rom com, except the behavior and conventions actually are taken from 2024, and with no apologies. The woman says the word “****ing” a lot, and no one treats this as inappropriate or unusual. There is bisexuality and poly. Society is feminized. Of course opinions will differ on these cultural issues, but the movie is made with conviction and so it is truly a tale of modern romance. Who in the movie is in fact the emptiest shell? Opinions will differ.

Zendaya dominates the screen — for how long has it been since we have had an actress this central and this charismatic?

Also, I quite like the new Beyonce album, and Metaculus estimates the chance of an H5N1 pandemic at about two percent.