Category: Political Science

Understanding politics

I was wondering why there had been so much talk recently of ramping up antitrust attacks on Google. Now I know. This is the way politics works. See my letter on antitrust protectionism (pdf) if you need more.

Symposium on Paul Collier

You will find a Collier essay on democracy and development along with numerous comments, including from Bill Easterly and Nancy Birdsall, all courtesy of Boston Review.

Easterly is not happy:

I have been troubled by Paul Collier’s research and policy advocacy for

some time. In this essay he goes even further in directions I argued

were dangerous in his previous work. Collier wants to de facto

recolonize the “bottom billion,” and he justifies his position with

research that is based on one logical fallacy, one mistaken assumption,

and a multitude of fatally flawed statistical exercises.

Nancy Birdsall suggests that donors support more investment in policing. She also notes:

The economy of sub-Saharan Africa–including Nigeria and South Africa–is smaller than the economy of New York City.

There is much more at the link.

Administrative costs, a simple point or two

Andrew Gelman serves up some links. Mankiw's addendum serves up some more.

Public sector programs usually have higher administrative costs — all relevant costs considered — than corresponding private sector programs. The public sector program is funded by taxation. That means the public sector doesn't have to worry so much about marketing or meeting payroll on commercial revenue alone. That will bring significant cost savings on administrative matters. But you can't stop counting there.

The deadweight loss from taxation is perhaps twenty percent or more. (It depends on which tax you consider as "the marginal tax" and there is not a simple factual answer to that question.) That should be factored into any comparison, even if you define that cost as "not an administrative cost."

The public sector also engages in less monitoring of who receives its services. If you're 67 and have worked a lifetime in this country, usually you can receive Medicare benefits. The "indiscriminate" nature of the program may be either a net social cost or a net social benefit but certainly it should not be counted as zero or ignored.

If you favor "indiscriminate" programs over targeted programs, OK. But the accompanying lesson is not one about the relative efficiency of the public sector at a comparable task. The lesson is that sometimes the public sector can be more effective when you don't wish to discriminate in supplying a particular kind of service.

TANSTAAFL.

Should “Fairfax County” become a city?

Should Fairfax County become a proper city? It has over a million people, many more than Washington, D.C. The bottom line seems to be this:

The basis for the idea is largely tactical — under state law, cities

have more taxing power and greater control over roads than counties do

— and it led to more than a few snickers about the thrilling nightlife

in downtown Fairfax (punch line: there isn't any).

Natasha could no longer say "We are from Washington":

If Fairfax does become a city, it would instantly become one of the largest in the nation, the size of San Antonio or San Jose.

It would also diverge dramatically from the stereotype of the gritty

metropolis. Fairfax enjoys many of the benefits — wealth and jobs —

and few of the detriments — crime, troubled schools — of a large

urban center. With a median household income of $105,000, it is the

wealthiest large county in the nation. Among large school systems, it

boasts the highest test scores. And it has the lowest murder rate among

the nation's 30 largest cities and counties.

One question is why this rather uncoordinated mix works so well. Federal dollars, diversity of immigration, and diversity of planning strategies all can be cited. The latter factor probably means we should not touch the status quo. And by the way, almost all of our nightlife is Korean but it does exist.

The value of personal experience

It's rare that I read something about Barack Obama which I had not already seen:

Barack Obama's last visit to Russia,

as a senator in 2005, did not end so well. He was detained by the

security services at an airport near Siberia for three hours, locked in

a lounge, his passport confiscated, like a scene from a John le Carré novel.

The Russians later called it a “misunderstanding.”

A theory of Fed announcements

If you've been paying attention, the Fed likes to release bad news

after the markets close on Friday afternoon. The past couple weeks,

they've announced the failures of small regional banks.

Well today [referring to a Friday], they announced something just a little bit bigger – the government bailout/takeover of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac,

the two large mortgage finance guarantors. The markets have been

expecting this for a while, but obviously not everyone was expecting it

as their stock prices were $5.50 and $4 respectively when the market

closed today. If everyone was expecting this, then those prices would

have been a lot closer to zero.

Here is more.

Cap-and-trade-war

Eric Posner and Paul Krugman defend the use of tariff threats against polluting countries, such as China. I'll outsource my response to an earlier post by Matt Yglesias:

The bottom line about the international aspects of climate change is that the very idea of an effective response assumes

the existence of a generally cooperative international environment. It

doesn’t assume the non-existence of the odd “rogue” state here or

there, but it assumes the absence of any kind of serious great power

rivalries. Not just China, but also India and probably Russia, Brazil,

and Indonesia as well are going to need to cooperate in a serious way

with the OECD nations on this. And I just don’t see how you’re going to

get where you need to get through coercion. If anything, I think

attempted economic coercion of China is more likely to wind up breaking

down solidarity between the US, EU, and Japan than anything else.

First, we impose our carbon tariff. Then suddenly Airbus and European

car companies are getting all kinds of sales because the EU hasn’t

followed suit. Now not only are the Chinese mad at us, we’re mad at the

Europeans. Optimistically, at this point everyone decides coercion is unworkable and we start to back away.

I'll say it again: the current version of Waxman-Markey will make things worse. Keep in mind by the time we are slapping those 2020 tariffs on China, we won't have made much progress on emissions ourselves. How would we feel, and how would it influence our domestic politics, if the Chinese demanded we pass Waxman-Markey, while polluting at a high level themselves, or otherwise they will stop buying our Treasury securities?

When No Means Yes

… Having voted against the administration's climate change bill on the record means that at least some of these House Democrats will be able to vote for what emerges from a House-Senate conference later in the year. Therefore, the chances of a climate bill being enacted this year is now much greater than it was 24 hours ago.

That's the ever-perceptive Stan Collender on the politics of the climate change bill.

Regulation and Distrust

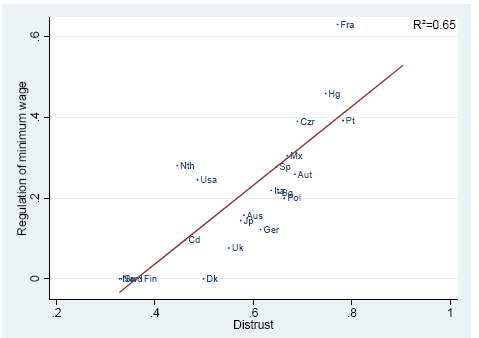

In an interesting paper, Aghion, Algan, Cahuc and Shleifer show that regulation is greater in societies where people do not trust one another. The graph below, for example, shows that societies with a greater level of distrust have stronger minimum wage laws. Note that the result is not that distrust in markets is associated with stronger minimum wages but that distrust in general is associated with greater regulation of all kinds. Distrust in government, for example, is positively correlated with regulation of business. Or to put it the other way, trust in government (as well as other institutions) is associated with less regulation.

Aghion et al. argue that the causality flows both ways on the regulation-distrust nexus. Distrust makes people turn to government but in a society with a lot of distrust government is often corrupt and this makes people distrust even more. Crucially, when people distrust others they invest not in the highest return projects but in human and physical capital that is complementary to distrust–for example, they invest in human capital that helps them bond with their group/tribe/family rather than in human capital that helps them to bond with “outsiders” and they invest in physical capital that is more difficult to expropriate rather than in easier to expropriate capital, even though in both cases the latter investments may be the all-else-equal higher return investments. Such distrust traps are quite similar to Bryan Caplan’s idea traps.

Aghion et al. argue that the causality flows both ways on the regulation-distrust nexus. Distrust makes people turn to government but in a society with a lot of distrust government is often corrupt and this makes people distrust even more. Crucially, when people distrust others they invest not in the highest return projects but in human and physical capital that is complementary to distrust–for example, they invest in human capital that helps them bond with their group/tribe/family rather than in human capital that helps them to bond with “outsiders” and they invest in physical capital that is more difficult to expropriate rather than in easier to expropriate capital, even though in both cases the latter investments may be the all-else-equal higher return investments. Such distrust traps are quite similar to Bryan Caplan’s idea traps.

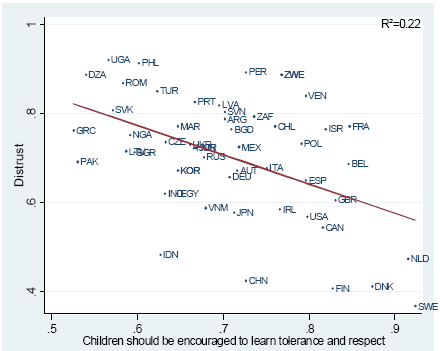

Thus, societies with a lot of distrust generate regulation and corruption and citizens who don’t have the skills or preferences to break out of the distrust equilibrium. Consider, for example, that in societies with a lot of distrust parents are less likely to consider it important to teach their children about tolerance and respect for others.

Insightful books on politics, written by politicians

That is another question I was asked yesterday, here are a few nominations:

2. James Madison and John Adams, for the latter Discourses on Davila.

3. Some of Richard Nixon, scattered.

4. Ulysses S. Grant.

5. Tocqueville, J.S. Mill and some other political writers were also politicians of a sort but I am not counting them as I do not view their contributions as stemming so directly from their political experience. Along these lines, you could try John Kenneth Galbraith's book about being ambassador to India.

6. Winston Churchill is a beautiful writer and important historian but I am not sure how insightful he is about politics.

7. Denis Healey, Time of My Life.

8. I've yet to read the new book by Zhao Ziyang.

9. Willy Brandt, My Life in Politics.

My knowledge is weak in this area (here is a list of Canadian political autobiographies and I know not a single one) and Google is surprisingly unhelpful; what else am I missing? And why are there not more? Are politicians so drunk with self-deception that they cannot write insightful books?

Three word explanations

Median voter theorem.

It's my first-cut account of a lot of what is going on in the newspaper headlines. Yet somehow I rarely see it mentioned, even when I read very prominent social scientists commenting on current policy.

I thank Garett Jones for a useful conversation behind this blog post.

*Disrobing the Aboriginal Industry*

The authors are Frances Widdowson and Albert Howard and the subtitle is The Deception Behind Indigenous Cultural Preservation. Here is one good two-sentence excerpt:

The "evidence" from "oral histories" is even more problematic when economic interests are involved. Oral histories have been known to change when a claim is necessary to obtain access to valuable resources.

This book is too polemic for my tastes and it doesn't try hard enough to understand the other side of the issue. But it makes many very good points backed up by many very real examples. It is strongest when arguing against the lowering of intellectual standards for arguments made on behalf of indigenous groups.

Credible threats

Here is one of them:

Ms. Feinstein has threatened to vote against Mr. Obama’s health care bill if it draws Medicare funds from high-cost areas like California to low-cost areas of the country.

She is, of course, a Democrat and a progressive. The article is instructive throughout.

Blaming the Republicans

Ryan Avent has a good post and I agree with much of it (and read him as expressing a good deal of agreement with me). I do, however, disagree with one part:

…if Waxman-Markey is a bad bill, then it is a bad bill largely because

the minority party has an energy plan that scarcely recognises the

threat of climate change as a problem. This guarantees that the vote

will be close, which guarantees that Democrats will have to wheel and

deal and wheel and deal to get the votes they need–the last Democrat to

be converted can name his price. It's a little silly to complain about

the imperfect bill Democrats have crafted, when the Republican minority

has basically forced them to build a law that every last Democrat can

accept.

I don't mean to pick on Ryan but I am seeing this idea growing in influence and I wish to push on it a bit. (By the way, here is his follow-up post.) A few points:

1. Negative claims about Republican politicians are, in fact, usually true. I don't wish to defend them or make you dislike them less.

2. If a policy idea cannot survive the opposition being partisan and also lying about it, I submit the policy idea is not such a good one. You can blame the opposition with all the justice in the world on your side, but still the idea has major, major problems.

3. The notion of a "minimum winning coalition" is commonplace in political science. Maybe the idea isn't as universal as its early proponents claimed, but still it is an important force in shaping political equilibria. If a policy idea cannot survive being turned into a "minimum winning coalition" version of itself…well…see #2.

4. Both the Republicans and the Democrats share some common problems and they are known as voters. And special interest groups. If your plan cannot survive the influence of voters, and special interest groups…well…see #2.

5. Many government programs can in fact survive all of these negative influences and still emerge as good ideas.

6. The Democrats do in fact rule by more than one seat in both houses of Congress. So maybe the marginal Democratic legislators don't have so much bargaining power after all. You can cite 60+ in the Senate but of course this is endogenous to what the Democrats themselves think public opinion will bear. There is a reason why the Democratic establishment does not, as Matt Yglesias so often recommends, abolish the 60+ requirement. Often they prefer inaction, combined with the ability to blame the Republicans for such. See #4. The often-sad truth is that the Democrats as a whole prefer to tailor policy to pander to their "worst" members.

7. If indeed "the revolution is over" it is a question of critical importance, for progressives, what lessons to take away from the experience. I'm not yet sure what are the correct lessons, from a progressive point of view (Robin Hanson and I have been chatting about this and I hope to blog it more soon). Deep in my bones, however, I feel that if the main takeaway were "the Republicans were at fault," that a significant learning opportunity will have been missed.

Is the revolution over?

Megan McArdle writes:

There's a lot of sadness on liberal blogs these days. What happened to

Hope and Change? Climate change is coming sometime next year, maybe.

Financial regulation also isn't coming anytime soon, and what's

proposed is the minimum set of politically feasible propositions rather

than a sweeping overhaul. And health care?

There is more at the link and I suspect it is mostly or fully correct. Here is Ezra on health care reform and the very big chance that it might fail. I'd just like to repeat a simple question I asked at the beginning of the Obama administration: which would you rather have, the fiscal stimulus or $775 billion in public health programs?

Even better, how about $300 billion in stimulus — the immediate stuff like aid to state governments — and $475 billion in public health programs?

At the time no one except a few progressives thought such a question was particularly relevant.

Note that the economy has seemed to stabilize, more or less, and well under ten percent of the stimulus money has been spent to date. Moving forward, if no further major programs will be put into place, how would you like to spend the rest of that cash?

Seriously.

And I don't mean this post as a poke at Democrats in particular. Conservatives, libertarians, etc. all commit their own versions of this error, at least if they find their way to power. The basic mechanism is simply that policy advocates underestimate the opportunity costs of the measures they propose, as they tend to see those measures as more "win-win" than others are willing to believe.