Category: Science

Do older economists write differently?

The scholarly impact of academic research matters for academic promotions, influence, relevance to public policy, and others. Focusing on writing style in top-level professional journals, we examine how it changes with age, and how stylistic differences and age affect impact. As top-level scholars age, their writing style increasingly differs from others’. The impact (measured by citations) of each contribution decreases, due to the direct effect of age and the much smaller indirect effects through style. Non-native English-speakers write in different styles from others, in ways that reduce the impact of their research. Nobel laureates’ scholarly writing evinces less certainty about the conclusions of their research than that of other highly productive scholars.

Here is the full NBER paper by Lea-Rachel and Daniel S. Hamermesh.

Strong and Weak Link Problems and the Value of Peer Review

Adam Mastroianni’s has an excellent post on strong-link vs weak-link problems in science. He writes:

Weak-link problems are problems where the overall quality depends on how good the worst stuff is. You fix weak-link problems by making the weakest links stronger, or by eliminating them entirely.

Food safety is a weak link problem, bank or computer security is a weak-link problem, many production processes are weak-link, also called O-ring problems.

[But] some problems are strong-link problems: overall quality depends on how good the best stuff is, and the bad stuff barely matters….Venture capital is a strong-link problem: it’s fine to invest in a bunch of startups that go bust as long as one of them goes to a billion.

….Here’s the crazy thing: most people treat science like it’s a weak-link problem.

Peer reviewing publications and grant proposals, for example, is a massive weak-link intervention. We spend ~15,000 collective years of effort every year trying to prevent bad research from being published. We force scientists to spend huge chunks of time filling out grant applications—most of which will be unsuccessful—because we want to make sure we aren’t wasting our money.

These policies, like all forms of gatekeeping, are potentially terrific solutions for weak-link problems because they can stamp out the worst research. But they’re terrible solutions for strong-link problems because they can stamp out the best research, too. Reviewers are less likely to greenlight papers and grants if they’re novel, risky, or interdisciplinary. When you’re trying to solve a strong-link problem, this is like swallowing a big lump of kryptonite.

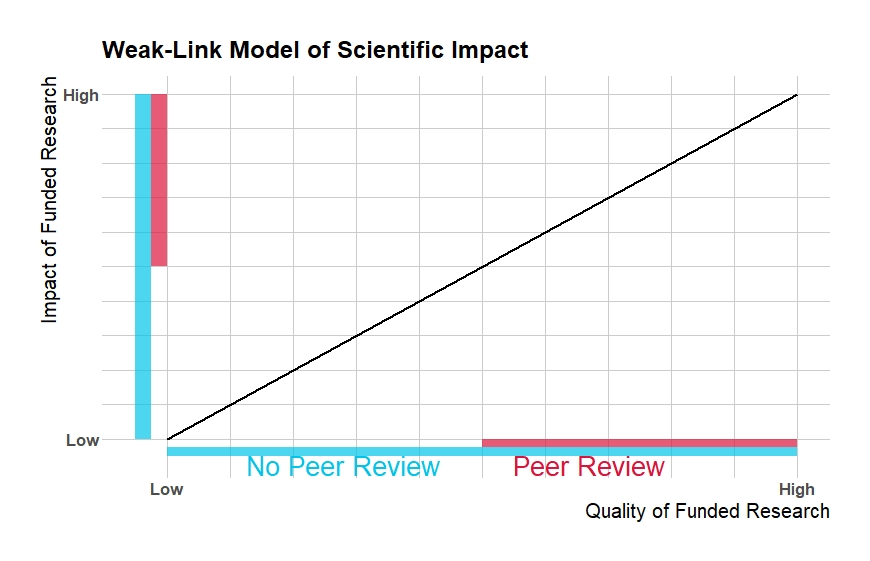

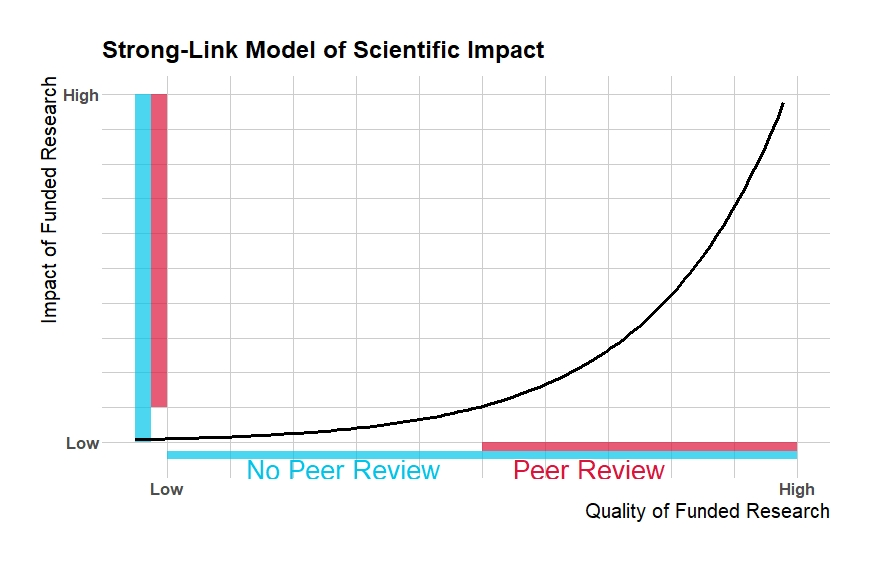

At Maximum Progress, Max Tabarrok has some nice diagrams illustrating the issue:

If you have a weak-link view of science, you’d think peer review works something like this. The relationship between quality and eventual impact is linear, or perhaps even bowed out a bit. Moving resources from low input quality projects to average ones is at least as important to eventual impact as moving resources from average projects to high quality ones.

In a strong-link model of science, filtering the bottom half of the quality distribution is less important to final impact [because the impact of research is highly non-linear].

Even though peer review has the same perfect filter on the quality distribution, it doesn’t translate into large changes in the impact distribution. Lots of resources are still being given to projects with very low impact. Although the average input quality increases by the same amount as in the weak link model, the average final impact barely changes. Since peer review has significant costs, the slightly higher average impact might fail to make up for the losses in total output compared to no peer review.

This is a simplified model but many of the simplifying assumptions are favorable for peer review. For example, peer review here is modeled as a filter on the bottom end of the quality distribution…But if peer review also cuts out some projects on the top end, its increase of the average impact of scientific research would be muted or even reversed.

Eight Things to Know about LLMS

A good overview from computer scientist Samuel R. Bowman of NYU, currently at Anthropic:

1. LLMs predictably get more capable with increasing investment, even without targeted innovation.

2. Many important LLM behaviors emerge unpredictably as a byproduct of increasing investment.

3. LLMs often appear to learn and use representations of the outside world.

4. There are no reliable techniques for steering the behavior of LLMs.

5. Experts are not yet able to interpret the inner workings of LLMs.

6. Human performance on a task isn’t an upper bound on LLM performance.

7. LLMs need not express the values of their creators nor the values encoded in web text.

8. Brief interactions with LLMs are often misleading.

Bowman doesn’t put it this way but there are two ways of framing AI risk. The first perspective envisions an alien superintelligence that annihilates the world. The second perspective is that humans will use AIs before their capabilities, weaknesses and failure modes are well understood. Framed in the latter way, it seems inevitable that we are going to have problems. The crux of the dilemma is that AI capability is increasing faster than our AI understanding. Thus AIs will be widely used long before they are widely understood. You don’t have to believe in “foom” to worry that capability and control are rapidly diverging. More generally, AIs are a tail risk technology, and historically, we have not been good at managing tail risks.

What do we need to talk to whales?

We detail a scientific roadmap for advancing the understanding of communication of whales that can be built further upon as a template to decipher other forms of animal and non-human communication. Sperm whales, with their highly developed neuroanatomical features, cognitive abilities, social structures, and discrete click-based encoding make for an excellent model for advanced tools that can be applied to other animals in the future. We outline the key elements required for the collection and processing of massive datasets, detecting basic communication units and language-like higher-level structures, and validating models through interactive playback experiments. The technological capabilities developed by such an undertaking hold potential for cross-applications in broader communities investigating non-human communication and behavioral research.

That is from a new research paper by Jacob Andreas, et.al., and the (ungated) article offers considerable detail on exactly how to do this. They already have funding from both Dalio and Audacious.

From the comments, on AI safety

This is from Richard Ngo, who works on the governance team at OpenAI:

A few points:

1. I agree that the alignment community has generally been remiss in not trying hard enough to clarify the arguments in more formal papers.

2. The only peer-reviewed paper making the case for AI risk that I know of is: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/aaai.12064. Though note that my paper (the second you linked) is currently under review at a top ML conference.

3. I don’t think that a formal model would shed much light here. My goal in writing my paper was to establish misaligned power-seeking AGI as a credible scientific hypothesis; I think that most who think it’s credible would then agree that investigating it further should be a key priority, whether or not their credences are more like 10% or more like 90%.

From this batch of comments. Here is Richard on Twitter.

This GPT-4 answer speaks for itself

TC: Which is the leading attempt to publish a canonical paper on AGI risk, in a leading science journal, refereed of course. The paper should have a formal model or calibration of some sort, working toward the conclusion of showing that the relevant risk is actually fairly high. Is there any such thing? Please answer as would a leading scientific expert in the relevant fields, including computer science and possibly also population ecology, systems theory, and other possible areas.

GPT-4: As a leading scientific expert, I must clarify that while there are numerous papers discussing various aspects of AGI (Artificial General Intelligence) risk, no single paper can be labeled as the “canonical” paper on the subject. It is worth noting that the field of AGI risk is interdisciplinary, involving computer science, artificial intelligence, ethics, population ecology, systems theory, and other domains. Consequently, the body of research on AGI risk is diverse, with various approaches and models, some of which may involve formal calibration.

One paper that may be of interest to you is “The Malicious Use of Artificial Intelligence: Forecasting, Prevention, and Mitigation” by Brundage et al., published in 2018. This paper, co-authored by experts from various institutions, including OpenAI, the University of Oxford, and the Center for a New American Security, discusses potential risks from the malicious use of AI and offers recommendations for researchers, policymakers, and industry practitioners. While this paper does not provide a formal calibration model, it does shed light on the potential risks associated with AGI.

Another important work in the field is Nick Bostrom’s book “Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies,” which discusses the risks associated with the development of AGI and offers possible strategies to mitigate those risks. Bostrom’s work has been influential in shaping the discourse on AGI risk, but it is not a refereed journal article….[and some concluding GPT blather]

Perhaps I am too quick to the draw here, but I don’t see this answer as far from “nothing, there is no such paper.” Comments are open, of course, if you can surpass GPT-4, which perhaps is better at evolving into a world-destroying entity than it is at finding citations. Further prods did not change the basic answer, and if anything GPT models tend to confabulate or hallucinate entries, not deny them. Or perhaps in this case it is hiding the refereed articles and deceiving us?

And maybe I’ve missed it, but I’ve also never seen Scott Alexander or Zvi point to such a paper, or even a good example of a rejected paper aiming in this direction. Nor have I seen them make a big stink about the absence of such a paper, though in virtually any other area they will hit you with a fire hose of citations and links to published models in referred journals.

I’ve also asked a whole bunch of “people who ought to know” and not received a single concrete answer, one such individual responding immediately with the answer “zero.”

In part, I would like to encourage those fascinated with AGI risk to try to create and publish such a paper, or perhaps to fund it or otherwise encourage it. Something more systematically fleshed out than “10 reasons why lists of 10 reasons might be a winning strategy.” It would go a long way to giving the idea more credibility in the scientific community, not to mention with yours truly. How about Nature? Science? Somewhere else? I know top journals can be closed or unfair, but at the very least you can put the paper and the associated referee reports on-line for the rest of us to judge. And then try it in a lesser journal, it still will get traction and you will get valuable feedback, of a very different kind than from on-line forums.

If the chance of existential risk from AGI is 99 percent, or 80 percent, or even 30 percent, surely some kind of modeled demonstration of the basic mechanics and interlocking pieces is possible. Indeed a certain kind of clarity should be evident, at least conditional on the more extreme views being correct. In general, I am not a fan of the “you should work on this!’ strategy, but if you think the whole future of the entire world is at stake…shouldn’t you be obsessed with working on such a thing, if only to convince the rest of us? And in as many different formats as possible, including the methods most commonly recognized by the scientific community?

In the meantime, if you are a young person interested in this issue, and you observe such a paucity of refereed, published model-based papers in the area — consider any area just to get your mind off the fraught and emotional topic of AGI existential risk — what would you infer from that absence?

And what if said community of commentators almost universally insisted they were the most extreme of rationalists?

Now none of this means the claims about extreme risk are wrong. But you can think of it as a kind of propaedeutic to reading the literature and current debates.

Addendum: I have looked at papers such as these:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2206.13353, https://arxiv.org/abs/2209.00626, https://arxiv.org/abs/2109.13916

Whatever you think of them, they are not close to counting for my search.

The Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty and existential AGI risk

The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, activated in 1970, has been relatively successful in limiting nuclear proliferation. When it comes to nuclear weapons, it is hard to find good news, but the treaty has acted as one deterrent of many to nation-states acquiring nuclear arms. Of course the treaty works, in large part, because the United States (working with allies) has lots of nuclear weapons, a powerful non-nuclear military, de facto control of SWIFT, and so on. We strongly encourage nations not to go acquiring nuclear weapons — just look at the current sanctions on Iran, noting the policy does not always succeed.

One approach to AI risk is to treat it like nuclear weapons and also their delivery systems. Let the United States get a lead, and then hope the U.S. can (in conjunction with others) enforce “OK enough” norms on the rest of the world.

Another approach to AI risk is to try to enforce a collusive agreement amongst all nations not to proceed with AI development, at least along certain dimensions, or perhaps altogether.

The first of these two options seems obviously better to me. But I am not here to argue that point, at least not today. Conditional on accepting the superiority of the first approach, all the arguments for AI safety are arguments for AI continuationism. (And no, this doesn’t mean building a nuclear submarine without securing the hatch doors.) At least for the United States. In fact I do support a six-month AI pause — for China. Yemen too.

It is a common mode of presentation in AGI circles to present wordy, swirling tomes of multiple concerns about AI risk. If some outside party cannot sufficiently assuage all of those concerns, the writer is left with the intuition that so much is at stake, indeed the very survival of the world, and so we need to “play it safe,” and thus they are lead to measures such as AI pauses and moratoriums.

But that is a non sequitur. The stronger the safety concerns, the stronger the arguments for the “America First” approach. Because that is the better way of managing the risk. Or if somehow you think it is not, that is the main argument you must make and persuade us of.

(Scott Alexander has a new post “Most technologies aren’t races,” but he doesn’t either choose one of the two approaches listed above, nor does he outline a third alternative. Fine if you don’t want to call them “races,” you still have to choose. As a side point, once you consider delivery systems, nuclear weapons are less of a yes/no thing than he suggests. And this postulated take is a view that nobody holds, nor did we practice it with nuclear weapons: “But also, we can’t worry about alignment, because that would be an unacceptable delay when we need to “win” the AI “race”.” On the terminology, Rohit is on target. Furthermore, good points from Erusian. And this claim of Scott’s shows how far apart we are in how we consider institutional and also physical and experimental constraints: “In a fast takeoff, it could be that you go to sleep with China six months ahead of the US, and wake up the next morning with China having fusion, nanotech, and starships.”)

Addendum:

As a side note, if the real issue in the safety debate is “America First” vs. “collusive international agreement to halt development,” who are the actual experts? It is not in general “the AI experts,” rather it is people with experience in and study of:

1. Game theory and collective action

2. International agreements and international relations

3. National security issues and understanding of how government works

4. History, and so on.

There is a striking tendency, amongst AI experts, EA types, AGI writers, and “rationalists” to think they are the experts in this debate. But they are only on some issues, and many of those issues (“new technologies can be quite risky”) are not so contested. And because these individuals do not frame the problem properly, they are doing relatively little to consult what the actual “all things considered” experts think.

*A New History of Greek Mathematics*

I have read only about 30 pp. so far, but this is clearly one of the best science books I have read, ever. It is clear, always to the point, conceptual, connects advances in math to the broader history, explains the math, and full of interesting detail. By Reviel Netz. Here is a brief excerpt:

And this is how mathematics first emerges in the historical record: the simple, clever games accompanying the education of bureaucrats.

One of the best books of the year, highly recommended.

My excellent Conversation with Jessica Wade

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the summary:

She joined Tyler to discuss if there are any useful gender stereotypes in science, distinguishing between productive and unproductive ways to encourage women in science, whether science Twitter is biased toward men, how AI will affect gender participation gaps, how Wikipedia should be improved, how she judges the effectiveness of her Wikipedia articles, how she’d improve science funding, her work on chiral materials and its near-term applications, whether writing a kid’s science book should be rewarded in academia, what she learned spending a year studying art in Florence, what she’ll do next, and more.

Here is the opening bit:

COWEN: Let’s start with women in science. We will get to your research, but your writings — why is it that women in history were so successful in astronomy so early on, compared to other fields?

WADE: Oh, that’s such a hard question [laughs] and a fascinating one. When you look back at who was allowed to be a scientist in the past, at which type of woman was allowed to be a scientist, you were probably quite wealthy, and you either had a husband who was a scientist or a father who was a scientist. And you were probably allowed to interact with science at home, potentially in things like polishing the lenses that you might use on a telescope, or something like that.

Caroline Herschel was quite big on polishing the lenses that Herschel used to go out and look at and identify comets, and was so successful in identifying these comets that she wanted to publish herself and really struggled, as a woman, to be allowed to do that at the end of the 1800s, beginning of the 1900s. I think, actually, it was just that possibility to be able to access and do that science from home, to be able to set up in your beautiful dark-sky environment without the bright lights of a city and do it alongside your quite successful husband or father.

After astronomy, women got quite big in crystallography. There were a few absolutely incredible women crystallographers throughout the 1900s. Dorothy Hodgkin, Kathleen Lonsdale, Rosalind Franklin — people who really made that science possible. That was because they were provided entry into that, and the way that they were taught at school facilitated doing that kind of research. I find it fascinating they were allowed, but if only we’d had more, you could imagine what could have happened.

COWEN: So, household production you think is the key variable, plus the ability to be helped or trained by a father or husband?

The discussion of chirality and her science work is very interesting, though hard to summarize. I very much like this part, when I asked her about her most successful unusual work habit:

But just writing the [Wikipedia] biography of the person I was going to work with meant that I was really prepped for going. And if I’m about to see someone speak, writing their biography before means I get this. That’s definitely my best work habit — write the Wikipedia page of what it is that you are working on.

I don’t agree with her on the environment/genes issue, but overall a very good CWT, with multiple distinct parts.

Do women disagree less in science?

This paper examines the authorship of post-publication criticisms in the scientific literature, with a focus on gender differences. Bibliometrics from journals in the natural and social sciences show that comments that criticize or correct a published study are 20-40% less likely than regular papers to have a female author. In preprints in the life sciences, prior to peer review, women are missing by 20-40% in failed replications compared to regular papers, but are not missing in successful replications. In an experiment, I then find large gender differences in willingness to point out and penalize a mistake in someone’s work.

That is from a new paper by David Klinowski. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

My Conversation with Jonathan GPT Swift

Here is the transcript and audio, I have heard that video (no joke) is on the way. Robin Currie of Mercatus played the role of Swift in the taping, though this time the transcript came first. Here is part of the summary:

GPT Swift discusses his support for the Church of Ireland, his shift from the Whigs to the Tories, and his opposition to William Wood’s copper coinage in Ireland. He also talks about his works, including Gulliver’s Travels and A Modest Proposal, and his skepticism of moral and intellectual progress. Swift addresses rumors about his relationship with Esther Johnson and his fascination with scatological themes in his works. He also discusses his early life in England, his intellectual mentor Sir William Temple, and his jovial attitude towards death.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: Queen Anne: overrated or underrated? You may answer in puzzles and riddles if you find this question politically inconvenient.

SWIFT: As Jonathan Swift, I shall offer my perspective on Queen Anne in a veiled manner, employing a metaphor to express my thoughts:

Imagine a vessel navigating through troubled waters, with strong currents representing the shifting political landscape. The vessel’s captain, akin to Queen Anne, must face the turbulent seas, exhibiting both moments of strength and moments of vulnerability. Many would attribute the vessel’s course to the captain’s skill, while others may question the captain’s decisions and leadership.

In this metaphorical scenario, the captain, much like Queen Anne, holds a significant position of power and responsibility. However, the captain’s competence may be a subject of debate. Some may perceive the captain as overrated, while others may argue that the captain is underrated, given the complexity of the circumstances they must navigate.

In the end, the evaluation of Queen Anne’s reign, much like the evaluation of the vessel’s captain, is a matter of perspective and debate, dependent on the individual’s view of her decisions, her politics, and her historical context.

How about this for humor:

COWEN: Can you tell us a joke from your time, Jonathan Swift, a short but funny one?

SWIFT: I shall share a short jest that was popular during my time:

Why do we never tell secrets on a farm?

Because the potatoes have eyes and the corn has ears.

COWEN: So, what is a joke from your time that *you* would find funny?

SWIFT: My humor often leaned towards satire and irony. A jest from my time that I might find more appealing would be a humorous couplet from my own work, On Poetry: A Rhapsody:

“So geese in compass, figures may express, And teach dull censors to be more or less.”

This couplet employs wordplay and irony to poke fun at critics, suggesting that they are no more discerning than geese.

Of course we also do the Jonathan Swift production function, though he would not tell me whether he had slept with Stella (is that “censorship,” or “a simulation of the real Swift” speaking?). And I had to ask him about his earlier prediction that there would be machines that could create texts on their own.

As for method, here is TC:

Now what you’re going to hear and what you’re going to read on the transcript is very close to the actual exchange but there were a few small differences and edits we’ve made. Very often the GPT would begin the answer with, “As Jonathan Swift.” We simply took that out. Some of the longer answers, there were resummaries at the end. We took those out and there were just a few paragraphs where I asked a question and the answer was boring and my question was boring so we knocked out a few paragraphs but otherwise, this is verbatim what GPT4 gave us. I did not keep on repeating prompts trying to get the answer I wanted. This is really awfully close to the dialogue.

Do read the whole thing. It is too “textbook-y” in parts, but overall I was extremely impressed.

A brief observation on AGI risk and employee selection (from my email)

- Stunting growth now in the development of artificial intelligence just makes the probability of a bad future outcome more likely, as the people who are prosocial and thoughtful are more likely to be discouraged from the field if we attach a stigma to it. My view is that most people are good and care about others and our collective future. We need to maintain this ratio of “good people” in AI research. We can’t have this become the domain of malevolent actors. It’s too important for humanity.

That is from Ben R.

What should I ask Kevin Kelly?

From Wikipedia:

Kevin Kelly (born 1952) is the founding executive editor of Wired magazine, and a former editor/publisher of the Whole Earth Review. He has also been a writer, photographer, conservationist, and student of Asian and digital culture…

Among Kelly’s personal involvements is a campaign to make a full inventory of all living species on earth, an effort also known as the Linnaean enterprise. He is also sequencing his genome and co-organizes the Bay Area Quantified Self Meetup Group.

His Out of Control is a wonderful Hayekian book. His three-volume Vanishing Asia is one of the greatest picture books of all time. His new book (I haven’t read it yet) is Excellent Advice for Living: Wisdom I Wish I’d Known Earlier. Here is Kevin on Twitter, here is his home page.

I will be doing a Conversation with him, so what should I ask?

Machine Learning as a Tool for Hypothesis Generation

While hypothesis testing is a highly formalized activity, hypothesis generation remains largely informal. We propose a systematic procedure to generate novel hypotheses about human behavior, which uses the capacity of machine learning algorithms to notice patterns people might not. We illustrate the procedure with a concrete application: judge decisions about who to jail. We begin with a striking fact: The defendant’s face alone matters greatly for the judge’s jailing decision. In fact, an algorithm given only the pixels in the defendant’s mugshot accounts for up to half of the predictable variation. We develop a procedure that allows human subjects to interact with this black-box algorithm to produce hypotheses about what in the face influences judge decisions. The procedure generates hypotheses that are both interpretable and novel: They are not explained by demographics (e.g. race) or existing psychology research; nor are they already known (even if tacitly) to people or even experts. Though these results are specific, our procedure is general. It provides a way to produce novel, interpretable hypotheses from any high-dimensional dataset (e.g. cell phones, satellites, online behavior, news headlines, corporate filings, and high-frequency time series). A central tenet of our paper is that hypothesis generation is in and of itself a valuable activity, and hope this encourages future work in this largely “pre-scientific” stage of science.

Here is the full NBER working paper by Jens Ludwig and Sendhil Mullainathan.

The Era of Planetary Defense Has Begun

In Modern Principles of Economics, Tyler and I use asteroid defense as an example of a public good (see video below). As of the 5th edition, this public good wasn’t being provided by either markets or governments. But thanks to NASA, the era of planetary defense has begun. In September of 2022 NASA smashed a spacecraft into an asteroid. A new set of five papers in Nature has now demonstrated that not only did NASA hit its target, the mission was a success in diverting the asteroid:

DART, which was the size of a golf cart, collided with a Great Pyramid-sized asteroid called Dimorphos. The impact caused the asteroid’s orbit around another space rock to shrink — Dimorphos now completes an orbit 33 minutes faster than before the impact, researchers report1 today in Nature.

…As DART hurtled towards Dimorphos at more than 6 kilometres per second, the first part that hit was one of its solar panels, which smashed into a 6.5-metre-wide boulder. Microseconds later, the main body of the spacecraft collided with the rocky surface next to the boulder — and the US$330-million DART shattered to bits….the spacecraft hit a spot around 25 metres from the asteroid’s centre, maximizing the force of its impact….large amounts of the asteroid’s rubble flew outwards from the impact. The recoil from this force pushed the asteroid further off its previous trajectory. Researchers estimate that this spray of rubble meant Dimorphos’ added momentum was almost four times that imparted by DART.

…Although NASA has demonstrated this technique on only one asteroid, the results could be broadly applicable to future hazards…if a dangerous asteroid were ever detected heading for Earth, a mission to smash into it would probably be able to divert it away from the planet.