Claudia Goldin on the gender pay gap

The pdf of her Philadelphia paper is here. This is from the concluding section:

The reasoning of this essay is as follows. A gender gap in earnings exists today that greatly expands with age, to some point, and differs significantly by occupation. The gap is much lower than it had once been and the decline has been largely due to an increase in the productive human capital of women relative to men. Education at all levels increased for women relative to men and the fields that women pursue in college and beyond shifted to the more remunerative and career-oriented ones. Job experience of women also expanded with increased labor force participation. The portion of the difference in earnings by gender that was once due to differences in productive characteristics has largely been eliminated.

What, then, is the cause of the remaining pay gap? Quite simply the gap exists because hours of work in many occupations are worth more when given at particular moments and when the hours are more continuous. That is, in many occupations earnings have a nonlinear relationship with respect to hours. A flexible schedule comes at a high price, particularly in the corporate, finance and legal worlds.

A compensating differentials model explains wage differences by the costs of flexibility. The framework developed here shows why there are higher or lower costs of time flexibility and the underlying causes of nonlinearity of earnings with respect to time worked. Much has to do with the presence of good substitutes for individual workers when there are sufficiently low transactions costs of relaying information. Evidence from O*Net on occupational characteristics demonstrates that certain features of occupations that create time demands and reduce the degree of substitution across workers are associated with larger gender gaps.

Data for MBAs and JDs shows large increases in gender pay gaps with time since degree and also reveals the relationship between the increasing gender pay gap and the desire for time flexibility due to the arrival of children. Lower hours mean lower earnings in a nonlinear fashion. Lower potential earnings, particularly among those with higher-earning spouses, often means lower labor force participation. Pharmacists, on the other hand, have pay that is more linear with respect to hours of work. Female pharmacists with children often work part-time and remain in the labor force rather than exiting.

The paper is interesting throughout.

Addendum: Mary Ann Bronson, a job candidate from UCLA, has a new and interesting paper (pdf) on the gender gap across college majors and related issues. Here is another UCLA job market paper, by Gabriela Rubio, on why arranged marriages decline in frequency. This year, at Duke University, there are more female entering students in the Ph.d. program than male.

Arrived in my pile

1. Lars Peter Hansen and Thomas Sargent, Recursive Models of Dynamic Linear Economies.

2. Alberto Simpser, Why Governments and Parties Manipulate Elections.

3. Glenn Reynolds, The New School: How the Information Age Will Save American Education from Itself.

Cihan Artunç is studying legal pluralism in the Ottoman Empire

Here is the abstract from his job market paper, he is from Yale:

Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, non-Muslim Ottomans paid large sums to acquire access to European law. These protégés came to dominate Ottoman trade and pushed Muslims and Europeans out of commerce. At the same time, the Ottoman firm remained primarily a small, family enterprise. The literature argues that Islamic law is the culprit. However, adopting European law failed to improve economic outcomes. This paper shows that the co-existence of multiple legal systems, “legal pluralism,” explains key questions in Ottoman economic history. I develop a bilateral trade model with multiple legal systems and first show that legal pluralism leads to underinvestment by creating enforcement uncertainty. Second, there is an option value of additional legal systems, explaining why non-Muslim Ottomans sought to acquire access to European law. Third, in a competitive market where a subpopulation has access to additional legal systems, agents who have access to fewer jurisdictions exit the market. Thus, forum shopping explains protégés’ dominance in trade. Finally, the paper explains why the introduction of the French commercial code in 1850 failed to reverse these outcomes.

There is further interesting work at the link.

Assorted links

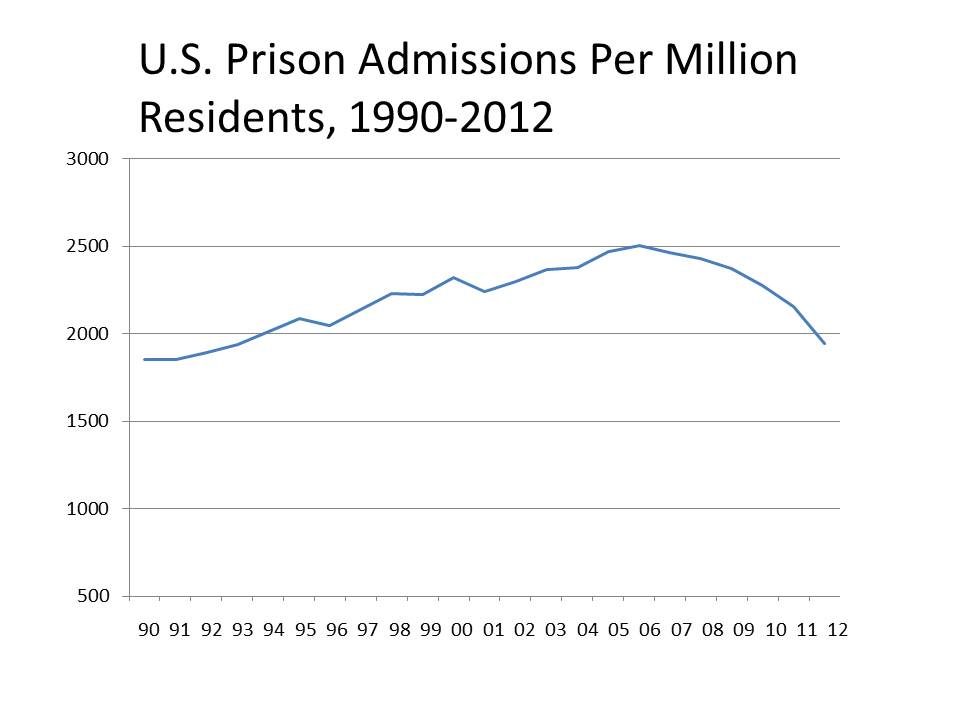

Prison Admission Rates are Falling

In an earlier post, I pointed out that after increasing for more than thirty years, prison populations have been begun to decline. Keith Humphreys further notes that the trend is even more dramatic when we look at the flow of people into prisons (rather than the stock).

In absolute numbers, the number of admissions in 2012 (609,800) was the lowest since 1999.

Drug-related imprisonments are especially down. In 1991, for example, 23% of the prisoner’s sentenced for more than one year were sentenced for drug related reasons (including 8.2% for drug possession). In 2011 only 16.6% of imprisonments for more than one year were for drug-related reasons (including 4.1% for drug possession.) This trend is likely to continue with further drug legalization.

Do Americans prefer hand-held foods?

Are there any dishes or foods that you would classify as typically, or even exclusively, “American?”

A number of iconic foods—hot dogs and hamburgers, snack food—are hand-held. They’re novelties associated with entertainment. These are the kinds of food you eat at the ballpark, buy at a fair and eventually eat in your home. I think that there is a pattern there of iconic foods being quick and hand-held that speaks to the pace of American life, and also speaks to freedom. You’re free from the injunctions of Victorian manners and having to eat with a fork and knife and hold them properly, sit at the table and sit up straight and have your napkin properly placed. These foods shirk all that. There’s a sense of independence and a celebration of childhood in some of those foods, and we value that informality, the freedom and the fun that is associated with them.

The resource costs of a gold standard

This is one of those topics which bugs me.

I’m not happy with counting the stock of “monetary gold” as the “resource costs of a gold standard,” as did Milton Friedman. We also hold stocks of oil, copper, and other commodities — how about books in libraries? — and no one considers inventories of those commodities as costs per se. For one thing, holding monetary gold in vaults still involves an option to convert into commodity uses and it may in essence serve as a useful commodity inventory for gold. Another way to put the point is that a properly capitalized bank can simply hold its gold in dental offices — or in wedding rings — if need be. How about if they hold their assets in the form of securities (T-Bills?) which can be, if needed, traded for gold mining stocks?

Is there a systematic market failure when it comes to locating inventories too close to major shipping centers? I don’t see why. But that’s arguably the same question as the one about the resource costs of a gold standard.

Or consider the Hotelling resource pricing rule, namely that a resource price should rise at the nominal rate of interest, with various adjustments for costs and changing costs and risk tossed in. Let’s say there is a gold standard and gold is also the medium of account. The price of gold rising at the nominal rate of interest thus means the general price level is falling at the nominal rate of interest. During the times of the classical gold standard, expected price inflation was roughly zero, but nominal interest rates were higher than zero. Either prices weren’t falling fast enough or nominal interest rates were too high or some mix of both. Say prices weren’t falling enough. Well, that is violating the Hotelling rule but in fact gold production is then falling short of an optimum, not exceeding it. Alternatively, you could toss in a liquidity rate of return on holding gold inventories and maybe then things would be just right.

A way to put this point more generally is that pricing some contracts in terms of a commodity does not itself create violations of the Hotelling rule. You might think that the liquidity premium on gold has to create an inefficiency, perhaps because social and private returns to liquidity differ. But do they, in the case of base money? Or isn’t the social return to liquidity arguably higher, if you see bankruptcy costs and benefits from thick capitalization using the liquid asset? In any case, the marginal liquidity return on money gold has to equal the marginal liquidity return on “commodity gold inventories” and then I am back to not being so sure there is a significant externality wedge.

It is unlikely that a final “all things considered” view will have the quantity of gold mined and held be just right. Yet as a first cut answer, postulating zero real resource costs for a gold standard is more reasonable than it might at first appear.

By the way, for macroeconomic reasons I’ve never favored a gold standard, but the resource cost argument has long seemed to me weak. All things considered, we might not end up digging up enough gold (liquidity) and that is the real worry we should hold.

The distributional incidence of QE and lower interest rates

A new McKinsey study has crossed my desk, “QE and ultra-low interest rates: Distributional effects and risks.” It offers a few estimates:

1. As a result of QE, governments in the US, UK, and Eurozone have benefited by about $1.6 trillion in lower debt service costs and profits remitted from central banks.

2. Households in those same countries have lost about $630 billion in reduced interest income.

3. Non-financial corporations have gained about $710 billion through lower debt service costs.

I would urge extreme caution in interpreting these or indeed any such results, as the nature of the no-QE-weaker-AD alternative scenario is hard to spell out and in any case would impose losses of its own. “Never reason from a pecuniary externality change” a wag once told me. Still, you can use those numbers as one example of a very rough “apply ceteris paribus assumptions to a macro problem” estimate.

One interesting takeaway from this report is that European life insurance companies may be in persistent financial trouble. Many life insurance policies are written for 40 or 50 years but the companies cannot find assets to match those durations. As the bonds they hold mature, they cannot easily reinvest in safe assets with yields comparable to what they are guaranteeing their policyholders. For instance some German life insurers are guaranteeing a return of 1.75 percent, but German ten year Bunds were yielding only about 1.54 percent (the report is from November). The insurance companies will either steadily lose money or be forced to seek out riskier investments, which is also to some extent prohibited by law and regulation. Here is one relevant Moody’s report, which explains why German life insurance companies are especially vulnerable. There are related readings here.

*F.A. Hayek and the Modern Economy*

That is a new volume edited by Sandra J. Peart and David M. Levy.

More than just the usual blah blah blah about Hayek, this book is full of original material. The book’s home page, with table of contents, is here.

And here is our recent MRUniversity class on Friedrich A. Hayek, and his Individualism and Economic Order.

Assorted links

I find this moderately sad (do not share)

One study of 7,000 New York Times articles by two professors at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School found that sad stories were the least shared because sadness is a low-arousal, negative state. People were more likely to share positive stories because it was a way to show generosity and boost their reputations. Sharing pleasant things in public made them appear nice themselves.

That is from a gated piece by John Gapper. To paraphrase Robin Hanson, “sharing isn’t about sharing.”

Interview with John Cochrane

There are many interesting bits from the interview, sometimes polemic bits too, here is one excerpt:

EF: What do you think are the biggest barriers to our own economic recovery?

Cochrane: I think we’ve left the point that we can blame generic “demand” deficiencies, after all these years of stagnation. The idea that everything is fundamentally fine with the U.S. economy, except that negative 2 percent real interest rates on short-term Treasuries are choking the supply of credit, seems pretty farfetched to me. This is starting to look like “supply”: a permanent reduction in output and, more troubling, in our long-run growth rate.

This part reminds me of some ideas in my own Risk and Business Cycles:

There is a good macroeconomic story. In a business cycle peak, when your job and business are doing well, you’re willing to take on more risk. You know the returns aren’t going to be great, but where else are you going to invest? And in the bottom of a recession, people recognize that it’s a great buying opportunity, but they can’t afford to take risk.

Another view is that time-varying risk premiums come instead from frictions in the financial system. Many assets are held indirectly. You might like your pension fund to buy more stocks, but they’re worried about their own internal things, or leverage, so they don’t invest more.

A third story is the behavioral idea that people misperceive risk and become over- and under-optimistic. So those are the broad range of stories used to explain the huge time-varying risk premium, but they’re not worked out as solid and well-tested theories yet.

The implications are big. For macroeconomics, the fact of time-varying risk premiums has to change how we think about the fundamental nature of recessions. Time-varying risk premiums say business cycles are about changes in people’s ability and willingness to bear risk. Yet all of macroeconomics still talks about the level of interest rates, not credit spreads, and about the willingness to substitute consumption over time as opposed to the willingness to bear risk. I don’t mean to criticize macro models. Time-varying risk premiums are just technically hard to model. People didn’t really see the need until the financial crisis slapped them in the face.

I’ve long believed the risk premium is the underexplored variable in macroeconomics and finally this is being rectified.

China fact of the day

More than 61 million children — about one-fifth of the kids in China — live in villages without their parents. Most are the offspring of peasants who have flocked to cities in one of the largest migrations in human history. For three decades, the migrants’ cheap labor has fueled China’s rise as an economic juggernaut. But the city workers are so squeezed by high costs and long hours that many send their children to live with elderly relatives in the countryside.

There is more here, via David Wessel.

Assorted links

1. La Repubblica covers Average is Over, in Italian.

2. Various economists on what we learned from 2013.

3. Scott Sumner also will be doing some guest-blogging at EconLog.

4. Scientists’ favorite jokes.

5. James Hamilton is right about Craig Pirrong.

6. Can you be paid to teach a university course which simply does not exist?

Green Wednesday: Colorado pot shops are opening today

Meanwhile, back in the so-called real world, Colorado is pursuing its legalization experiment to a logical conclusion:

Police were adding extra patrols around pot shops in eight Colorado towns that plan to allow recreational sales to anyone over 21 on Jan. 1. Officials at Denver International Airport installed new signs warning visitors their weed can’t legally go home with them.

And at a handful of shops, owners were scrambling to plan celebrations, set up coffee stations, arrange food giveaways and hire extra security to prepare for potential crowds and overnight campers ready to buy up to an ounce of legal weed.

While smoking pot has been legal in Colorado for the past year, so-called Green Wednesday represents another historic milestone for the decades-old legalization movement: the unveiling of the nation’s first legal pot industry.

Here are further details on Green Wednesday., including this: “Federal law says the drug’s possession, manufacture, and sale is illegal, punishable by up to life in prison…” I wonder if this experiment in federalism will survive our next Republican President. My prediction has long been that this kind of legalization will not persist, but the chance I am wrong has been rising.

Out-of-staters, by the way, can purchase only a quarter ounce at a time and are not supposed to carry the pot outside Colorado borders. There is also this:

Colorado projects $578.1 million a year in combined wholesale and retail marijuana sales to yield $67 million in tax revenue, according to the Legislative Council of the Colorado General Assembly. Wholesale transactions taxed at 15 percent will finance school construction, while the retail levy of 10 percent will fund regulation of the industry.