Are corporate profits a sinkhole for purchasing power?

That seems to be Krugman’s argument here, and here, excerpt:

So corporations are taking a much bigger slice of total income — and are showing little inclination either to redistribute that slice back to investors or to invest it in new equipment, software, etc.. Instead, they’re accumulating piles of cash.

I am confused by this argument. I would understand it (though not quite accept it) if corporations were stashing currency in the cupboard. Instead, it seems that large corporations invest the money as quickly as possible. It can be put in the bank and then lent out. It can purchase commercial paper, which boosts investment.

Maybe you are less impressed if say Apple buys T-Bills, but still the funds are recirculated quickly to other investors. This may not end in a dazzling burst of growth, but there is no unique problem associated with the first round of where the funds come from. If there is a problem, it is because no one sees especially attractive investment opportunities in great quantity. (To the extent there is a real desire to invest, the Coase theorem will get the money there.) That’s a problem at varying levels of corporate profits and some call it The Great Stagnation.

The same response holds if Apple puts the money into banks which earn IOR at the Fed and the money “simply sits there.” The corporations are not withholding this money from the loanable funds market but rather, to the extent there is a problem, the loanable funds market does not know how to invest it at a sufficiently high ROR.

If anything, large corporations are more likely to diversify out of the U.S. dollar, which could boost our exports a bit, a plus for a Keynesian or liquidity trap story.

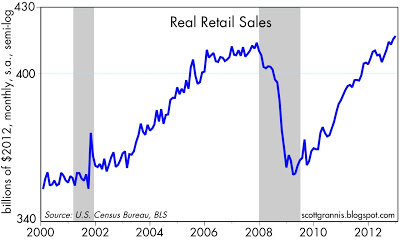

When one looks at the components of aggregate demand, retail sales, after a large and obvious hit, seem to be recovering. They are up 4.7% from Dec. 2011 to Dec. 2012 (pdf). If that is what a sinkhole looks like, as I said I am puzzled:

Here is the story of business investment minus corporate profits and that series doesn’t impress me (Krugman seems to think it is doing OK). The trickier variable of net investment you will find here and that looks worse.

By the way, Fritz Machlup considered related arguments in his 1940 book.

The “austerity” of 2011-2012 in the United States

It turns out that much more of it was phony than many people had realized. From David Farenthold, this is from today’s Washington Post:

To sketch the bill’s biggest impacts, The Washington Post focused on the 16 largest individual cuts. Each, in theory, sliced at least $500 million from the federal budget. Together, they accounted for $26.1 billion, two-thirds of the total.

In four of those cases, the real-world impact was difficult to measure. The Department of Homeland Security officially declined to comment about a $557 million reduction. The Department of State, the Department of Agriculture and the Federal Emergency Management Agency — whose cuts totaled $1.9 billion — simply did not answer The Post’s questions despite repeated requests over the past month.

Among the other 12 cases, there were at least seven where the cuts caused only minimal real-world disruptions or none at all.

Often, this was made possible by a little act of Washington magic. Agencies got credit for killing what was, in reality, already dead.

Here is the article, and I did chuckle at the last paragraph.

*Engineers of Victory*

The author is Paul Kennedy and the subtitle is The Problem Solvers who Turned the Tide in the Second World War. This is an excellent look at the managerial and logistics side of the war. My main regret — not really a criticism — is that the central role of economists was not given more attention. Haven’t you wondered how it was possible that say the American role in the War was started and finished in less than five years’ time? These days it can take that long to design, approve, and build a freeway interchange.

Here is a good review of the book. Here is a useful NYT review.

My real fear about the UK productivity puzzle

…Britain’s economists are also puzzling over why the economy remains moribund even though more and more people are in work. There are still about half a million fewer people working as full-time employees than there were before the 2008 crash, but the number of people in some sort of employment has surpassed the previous peak. Economists think the rise in insecure temporary, self-employed and part-time work, while a testament to the British labour market’s flexibility, helps to explain why economic growth remains elusive.

That is from Sarah O’Connor’s excellent FT piece about working for Amazon in their warehouses.

Assorted links

1. Virgil Storr’s Understanding the Culture of Markets, and Les Miserables ROK Air Force Parody (video).

2. Buy a ten-minute phone call with Cedric Ceballos (MIE).

3. What are we learning from measuring basketball performance with data-tracking cameras?

5. 8,000 people still can speak Texas German (with audio sample).

*What to Expect When No One’s Expecting*

That is the new book by Jonathan Last, which I liked very much. Last recently wrote “In the end, demography always wins” and you will find that view writ large in the book. He also wrote “Global demographics, not domestic policy, will control who comes and who goes.”

I am one who believes that the inability of a society to reproduce itself is per se a major problem, even if you don’t accept the most pessimistic fiscal interpretation of demographic collapse. Geopolitical influence also shall not be neglected. Here is one bit:

Low-fertility societies don’t innovate because their incentives for consumption tilt overwhelmingly toward health care. They don’t invest aggressively because, with the average age skewing higher, capital shifts to preserving and extending life and then begins drawing down. They cannot sustain social-security programs because they don’t have enough workers to pay for the retirees. They cannot project power because they lack the money to pay for defense and the military-age manpower to serve in their armed forces.

That is from Last’s WSJ essay, based on his book.

Here is an article on why Germany may be failing to raise its birth rate. And here is a good response to Dean Baker’s lack of worry about the fiscal issues.

Here is a critical Ruy Teixeira review of the book. Here is Reihan on the critique. Here is Maggie Gallagher.

How much does graduate school matter for being an economics professor?

There is a new paper, by Zhengye Chen, an enterprising undergraduate from the University of Chicago:

Of the 138 Ph.D. economics programs in the United States, the top fifteen Ph.D. programs in economics produce a substantial share of successful economics research scholars. These fifteen Ph.D. programs in turn get 59% of their faculty from only the top six schools with 39% coming from only two schools, Harvard and MIT. Those two schools are also the PhD origins for half of John Bates Clark Medal recipients. Details for assistant professors, young stars today, American Economics Association Distinguished Fellows, Nobel Laureates, and top overseas economics departments are also discussed.

There is much more here, and for the pointer I thank Lee Benham. I’ll add three points:

1. It has been evident for a while that the former “top six” is in some ways collapsing into a “top two,” namely Harvard and MIT.

2. I was surprised that NYU beats out Stanford for the #6 slot.

3. Two Nobel Laureates, John Hicks and James Meade, did not have a Ph.d at all.

*Here’s the Deal*

That is a new Kindle single by David Leonhardt, self-recommending!

Here are comments from Matt Yglesias.

Assorted links

1. The KFC culture that is Japan, and Pizza Hut innovation from China.

2. Critical review of Banerjee and Duflo.

3. What really happened in the Anglo-Irish deal?

4. Competitive wood planing, and does the CBO believe in the great stagnation?

5. Do people swap genes more easily than folk tales?

Health care cost control in Massachusetts, continuing the bad news string for ACA

Representatives from the state’s nonprofit health plans as well as national for-profit insurers doing business in Massachusetts estimated the “medical cost trend,” a key industry measure, will climb between 6 and 12 percent this year — higher than last year’s cost bump and more than double the 3.6 percent increase set as a target in a state law passed last year.

Here is more, and for the pointer I thank Jeffrey Flier.

Sentences about coal

Europe’s use of the fossil fuel spiked last year after a long decline, powered by a surge of cheap U.S. coal on global markets and by the unintended consequences of ambitious climate policies that capped emissions and reduced reliance on nuclear energy.

…In Germany, which by some measures is pursuing the most wide-ranging green goals of any major industrialized country, a 2011 decision to shutter nuclear power plants means that domestically produced lignite, also known as brown coal, is filling the gap . Power plants that burn the sticky, sulfurous, high-emissions fuel are running at full throttle, with many tallying 2012 as their highest-demand year since the early 1990s. Several new coal power plants have been unveiled in recent months — even though solar panel installations more than doubled last year.

Here is more.

How many niches can eBooks fill out?

I’m not sure this will work, but I suppose we will see:

Amazon’s business model has long been dependent on resellers of used books and other merchandise. But a U.S. patent that Amazon Technologies in Reno, Nev., received last week indicates that the mega-retailer has its sights on digital resale, including used e-books and audio downloads. According to the abstract, Amazon will be able to create a secondary market for used digital objects purchased from an original vendor by a user and stored in a user’s personalized data store.

Here is a bit more, and for the pointer I thank Chaim Katz. And here is news of a new Texas library that will offer digital books only.

Dinner with Fuchsia Dunlop

I am pleased to have shared a meal at A&J Manchurian restaurant, in Rockville with the charming Fuchsia Dunlop. You may recall that Fuchsia has written what I consider to be the very best Chinese cookbooks in English and indeed some of my favorite books of all time. She was in town to speak at Georgetown University and to promote her new book Every Grain of Rice: Simple Chinese Home Cooking.

Here were a few topics of conversation and related points:

1. To what extent did excellent Chinese food, in China, go underground during the 1960s and 70s, or to what extent did those traditions need to be reconstructed?

2. Why is there good Chinese food in Panama and Tanzania (my claim not hers), but not in most of Europe, least of all Italy? Why does Latin America have so little good Chinese food?

3. Should the advanced state of Chinese food in the 18th century, relative to European food, cause economists — including Adam Smith– to revise upward their estimates of Chinese standards of living?

4. Her books are effectively written, in part, because the points are continually reduced to their simplest elements, yet those simple bits are woven together to construct and reveal multiple layers of complexity.

5. The Chinese servers seemed unsurprised by her effortless fluency in Mandarin.

6. When speaking in the United States she is often taken to some local’s idea of a good Chinese restaurant. A&J was her proposal. She was surprised that northern Virginia has restaurants which are exclusively or in significant part Peruvian-Chinese, Indo-Chinese, and Korean-Chinese.

7. To what extent do we live in an unusual temporary bubble of easy foreign access to China?

8. I consider her Hunan book to be her most significant and original achievement, but Every Grain of Rice is the most useful single all-purpose Chinese cookbook she has written. It is especially good on the vegetarian side.

9. Each of us wished to defer dictatorial ordering rights to the other.

10. At what age do people learn or discover the determination to carve out a life of (relative) freedom for themselves? To what extent is their ability to achieve such a life the result of luck or of skill?

11. The cucumber salad in hot garlic sauce was very good. No cookies.

And first they came for the law professors…

Last week, it was reported that law school applications were on pace to hit a 30-year low, a dramatic turn of events that could leave campuses with about 24 percent fewer students than in 2010. Young adults, it seems, have fully absorbed the wretched state of the legal job market.

Beware most measures of government consumption

Garett Jones reports:

Here’s one big area where I think we should change what we call one type of government spending: Medicare and Medicaid. Currently, these types of spending are counted as transfer payments (BEA PDF here) and so when we measure GDP they show up in C, consumer purchases. I think they should show up in G, government purchases. These medical purchases are so tightly controlled by the government that doctors–oops, “medical service providers”–have become and should be considered government contractors just like defense contractors or construction firms.

Sometimes you hear or read talk of “government consumption plunging,” but sometimes what is happening is that health care expenditures are crowding out other programs, which is not exactly the same thing as fiscal consolidation.