Yglesias on Operation Warp Speed and the Republicans

Here’s Yglesias on Operation Warp Speed and the Republicans:

The debate over Operation Warp Speed wasn’t just a one-off policy dispute. Long before the pandemic, there was a conservative critique that the Food and Drug Administration is too slow and too risk-averse when it comes to authorizing new medications. Alex Tabarrok, a George Mason University economist, wrote about the “invisible graveyard” that could have been avoided if the FDA took expected value more seriously and considered the cost of delay in its authorization decisions.

The pandemic experience validated this criticism, which came to be embraced by some on the left as well — and it was about more than just vaccines. When it came to home Covid tests, Ezra Klein noted in the New York Times in 2021, “the problem here is the Food and Drug Administration. They have been disastrously slow in approving these tests and have held them to a standard more appropriate to doctor’s offices than home testing.”

And yet, just as the invisible graveyard was becoming seen and the debate was being won and just as a historical public-private partnership had sped vaccines to the public and saved millions, the Republicans abandoned the high ground:

…it’s not surprising that Democrats are comfortable with the bureaucratic status quo and hesitant to ruffle feathers at federal regulatory agencies. What’s shocking is that Republicans — the traditional party of deregulation, the party that argued for years that the FDA is too slow-footed, the party that saved untold lives by accelerating vaccine development under Trump — have abandoned these positions.

At the cusp of what should have been a huge policy victory, Republicans don’t brag about their success, and they have no FDA reform legislation to offer. Instead, they’ve taken up the old mantle of hard-left skepticism of modern science and the pharmaceutical industry.

It’s been painful to see all that has been gained now being lost. Libertarian economists and conservatives argued for decades that the FDA worried more about approving a drug that later turns out to be unsafe than about failing to approve a drug that could save lives; thus producing a deadly caution. But now the FDA is being attacked for what they did right, quickly approving safe vaccines. I hope that he is wrong but I fear that Yglesias is correct that the FDA may now get even slower and more cautious.

The irony of the present moment is that there is substantial backlash to the FDA’s approval of vaccines that haven’t turned out to be dangerous at all.

That’s only going to make regulators even more cautious. Right now the entire US regulatory state is taking essentially no heat for the slow progress on the next generation of vaccines, and an enormous amount of heat for the perfectly safe vaccines that it already approved. And the ex-president who pushed them to speed up their work on those vaccines is not only no longer defending them, he’s embarrassed to have ever been associated with the project.

Like I said, it’s a comical moment of Republican infighting. But it’s a very grim one for anyone concerned with the pace of scientific progress in America.

Klein on Construction

Here’s Klein writing about construction productivity in the New York Times:

Here’s something odd: We’re getting worse at construction. Think of the technology we have today that we didn’t in the 1970s. The new generations of power tools and computer modeling and teleconferencing and advanced machinery and prefab materials and global shipping. You’d think we could build much more, much faster, for less money, than in the past. But we can’t. Or, at least, we don’t.

…A construction worker in 2020 produced less than a construction worker in 1970, at least according to the official statistics. Contrast that with the economy overall, where labor productivity rose by 290 percent between 1950 and 2020, or to the manufacturing sector, which saw a stunning ninefold increase in productivity.

In the piquantly titled “The Strange and Awful Path of Productivity in the U.S. Construction Sector,” Austan Goolsbee, the newly appointed chairman of the Chicago Federal Reserve and the former chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Barack Obama, and Chad Syverson, an economist at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, set out to uncover whether this is all just a trick of statistics, and if not, what has gone wrong.

After eliminating mismeasurement and some other possibilities following Goolsbee and Syverson, Klein harkens back to our discussion of Mancur Olson’s Rise and Decline of Nations and offers a modified Olson thesis, namely too may veto points.

…It’s relatively easy to build things that exist only in computer code. It’s harder, but manageable, to manipulate matter within the four walls of a factory. When you construct a new building or subway tunnel or highway, you have to navigate neighbors and communities and existing roads and emergency access vehicles and politicians and beloved views of the park and the possibility of earthquakes and on and on. Construction may well be the industry with the most exposure to Olson’s thesis. And since Olson’s thesis is about affluent countries generally, it fits the international data, too.

I ran this argument by Zarenski. As I finished, he told me that I couldn’t see it over the phone, but he was nodding his head up and down enthusiastically. “There are so many people who want to have some say over a project,” he said. “You have to meet so many parking spaces, per unit. It needs to be this far back from the sight lines. You have to use this much reclaimed water. You didn’t have 30 people sitting in an hearing room for the approval of a permit 40 years ago.”

This also explains why measured regulation isn’t necessarily determinative. Regulation provides the fulcrum but it’s interest groups that man the lever.

Some of this is expressed through regulation. Anyone who has tracked housing construction in high-income and low-income areas knows that power operates informally, too. There’s a reason so much recent construction in Washington, D.C., has happened in the city’s Southwest, rather than in Georgetown. When richer residents want something stopped, they know how to organize — and they often already have the organizations, to say nothing of the lobbyists and access, needed to stop it.

This, Syverson said, was closest to his view on the construction slowdown, though he didn’t know how to test it against the data. “There are a million veto points,” he said. “There are a lot of mouths at the trough that need to be fed to get anything started or done. So many people can gum up the works.”

Read the whole thing.

The game theory of the balloons

One possibility is that the Chinese simply have been making a stupid mistake with these balloons (it is circulating on Twitter that this is not the first time they sent us a surveillance balloon — probably true).

A second possibility is that a faction internal to China wants to sabotage better relations between the U.S. and China.

A third possibility — most likely in my eyes — is that we do something comparable to them, which may or may not be exactly equivalent to a balloon. Nonetheless there is a tit-for-tat surveillance game going on, in which the two sides match each others moves, and have done so for years. The game evolves slowly, and occasionally all at once. The Chinese have been playing by the rules of the game, and the U.S. has decided to change the rules of the game. We may wish to send them a stern signal, we may wish to change broader China policy, we may think their balloons are too big and detectable for this to continue, USG might fear an internal leak, generating citizen opposition to balloon tolerance, or perhaps there simply has been a shift of factional powers within USG. Maybe some combination of those and other factors. So then USG “calls” China on the balloon, cashes in on the PR event, and simultaneously de facto announces that the old parameters of the former game are over. After all, in what is more or less a zero-sum game, why should any manifestation of said game be stable for very long? It isn’t, and it wasn’t. Now we will create a new game. A very small change in the parameters can lead to that result, and in that sense the cause of the new balloon equilibrium may not appear so significant on its own.

It was also a conscious decision when and where to shoot down the balloon.

Here is some NYT commentary, better than most pieces though it neglects our surveillance of them.

What should I ask Anna Keay?

I will be doing a Conversation with her, here is from Wikipedia:

Anna Julia Keay, OBE… is a British architectural historian, author and television personality and director of The Landmark Trust since 2012.

Born in the Scottish Highlands, and yes she is also the daughter of historian John Keay. I am a fan of her books, many on British architectural history or for that matter the crown jewels, but most recently The Restless Republic: Britain Without a Crown (or this link) about the 17th century interregnum. Here is her home page. Here is Anna on Twitter. And this:

The Landmark Trust is a British building conservation charity, founded in 1965 by Sir John and Lady Smith, that rescues buildings of historic interest or architectural merit and then makes them available for holiday rental. The Trust’s headquarters is at Shottesbrooke in Berkshire.

Five of those properties are in Vermont, it turns out. She lives (part-time) in what is perhaps the finest surviving merchant’s house in England.

So what should I ask her?

Sunday assorted links

1. Colombian judge uses ChatGPT to make a court decision. And use ChatGPT on your own pdfs (breakthroughs every day, people…). And how to build LLM apps that are more factual. And more on Bing/ChatGPT integration.

2. Transcript of my 2009 Bloggingheads episode with Robin Hanson. TC: “What I find funny about your view is that you’re a skeptic about medical science, about almost everything — except freezing your head. You think that’s the one thing that works.” There is audio too, and note this comes from the period when Robin and I were talking a lot (and writing together) on the phenomenon of disagreement.

3. Jupiter keeps on adding moons.

4. Ezra Klein on construction productivity (NYT).

5. How open source software shapes AI. Paper here.

6. Shift in the mean center of U.S. population over the centuries.

Haiti fact of the day

Around seven in 10 people in Haiti back proposed creation of an international force to help the national police fight violence from armed gangs who have expanded their territory since the 2021 assassination of President Jovenel Moise, according to a survey carried out in January.

Some 69% of nearly 1,330 people across Haiti said they supported an “international force” – which has been requested by the Haitian government – according to a survey from local business risk management group Agerca and consulting firm DDG.

Nearly 80%, however, said they believed Haiti’s PNH national police needed international support to resolve the problem of armed gangs, most saying it should be deployed immediately.

Here is the full story. So which is the democratic outcome?

The final collapse of CAPM?

The key purpose of corporate finance is to provide methods to compute the value of projects. The baseline textbook recommendation is to use the Present Value (PV) formula of expected cash flows, with a discount rate based on the CAPM. In this paper, we ask what is, empirically, the best discounting method. To do this, we study listed firms, whose actual prices and expected cash flows can be observed. We compare different discounting approaches on their ability to predict actual market prices. We find that discounting based on expected returns (such as variants on the CAPM or multi-factor model), performs very poorly. Discounting with an Implied Cost of Capital (ICC), imputed from comparable firms, obtains much better results. In terms of pricing methods, significant, but small, improvements can be obtained by allowing, in a simple and actionable way, for a more flexible term structure of expected returns. We benchmark all of our results with flexible, purely statistical models of prices based on Random Forest algorithms. These models do barely better than NPV-based methods. Finally, we show that under standard assumptions about the production function, the value loss from using the CAPM can be sizable, of the order of 10%.

That is from a new NBER paper by Nicholas Hommel, Augustin Landier, and David Thesmar. Via David Thesmar.

Will there by an H5N1 pandemic for humans?

Manifold Markets is currently putting the chance at 12%. That seems high to me, but maybe two percent? Which I still regard as leading to a high expected cost, to be clear. There is now mammal-to-mammal transmission. Zeynep Tufekci considers possible preparatory steps (NYT), including more surveillance.

Saturday assorted links

1. I am not convinced, but a novel and serious new hypothesis about unemployment.

2. Sam says.

3. Shruti and I discuss talent and India for Interintellect.

4. Might Google unveil on February 8? And Google announces Dreamix, a model that generates video based on prompts. Amazing what is happening every day. And further explanation here.

Industrial policy is the new globalization

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here goes:

It would be a mistake, however, to think that these [industrial] policies represent a move away from globalization. In fact they are an extension of globalization — and they likely will enable yet more globalization to come. That sounds counterintuitive, so let me explain.

Start with the domestic subsidies for green energy, as embodied in 2022’s Inflation Reduction Act. Those policies favor domestic firms in industries such as electric vehicles, batteries, and solar power. You could call that nationalism or even mercantilism. Yet those subsidies rely not only on a prior history of globalization but also an expected future for globalization. To the extent the US is able to extend its domestic battery production, it is because more lithium and other raw materials can be produced overseas and exported to the US. To the extent the US succeeds with its domestic solar industry, it is by drawing upon earlier advances in Spain, Germany and China — and undoubtedly future advances to come.

Even the most successful “nationalistic” industrial policies rely on a highly globalized world. If carried out strictly on a one-nation basis, industrial policy is doomed to fail. Globalization has been so thorough, and has gone so well, that at least a little industrial policy is now thinkable for many nations.

And this:

Just as globalization can enable or support nationalist industrial policy, so the converse is true. Assume that these various industrial policies meet with some degree of success, and that China, the EU and the US all become more self-sufficient in various ways. Those same political units are more likely to then embrace and support further globalization…

Some conservatives criticize globalization while praising industrial policy. They are playing right into the hands of the Davos globalizing elite. In fact, that is the best argument for many of these ideas: Today’s industrial policy is not an alternative to globalization. It is preparing the world for the next round of it.

I don’t think the Nat Cons have fully digested this lesson yet.

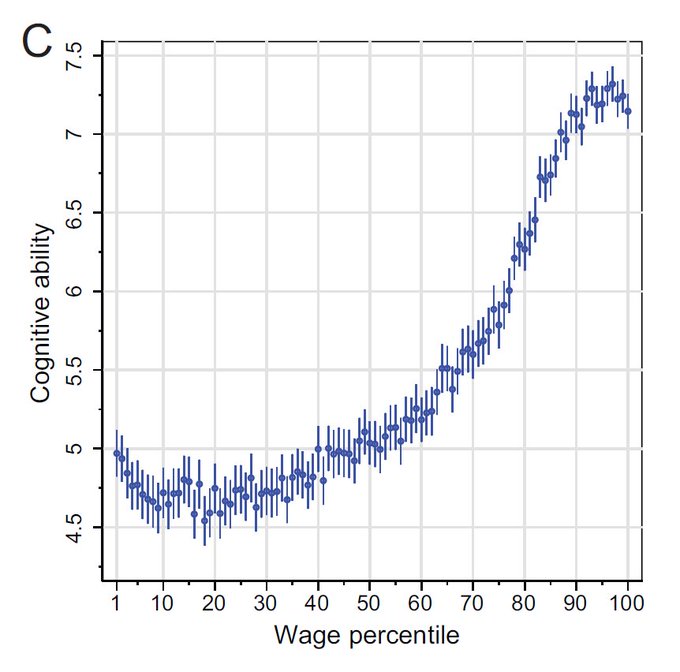

The plateauing of cognitive ability among top earners

Are the best-paying jobs with the highest prestige done by individuals of great intelligence? Past studies find job success to increase with cognitive ability, but do not examine how, conversely, ability varies with job success. Stratification theories suggest that social background and cumulative advantage dominate cognitive ability as determinants of high occupational success. This leads us to hypothesize that among the relatively successful, average ability is concave in income and prestige. We draw on Swedish register data containing measures of cognitive ability and labour-market success for 59,000 men who took a compulsory military conscription test. Strikingly, we find that the relationship between ability and wage is strong overall, yet above €60,000 per year ability plateaus at a modest level of +1 standard deviation. The top 1 per cent even score slightly worse on cognitive ability than those in the income strata right below them. We observe a similar but less pronounced plateauing of ability at high occupational prestige.

That is from a new paper by Marc Keuschnigg, Arnout van de Rijt3, and Thijs Bol.

Friday assorted links

1. David Brooks on AI (NYT). And a new AI tool for diagnosis. And what to do when you have to make a phone call in your second language. And connect Chat to your 3-D printer. And claims about Bing (speculative and unconfirmed). And Google might activate?

2. On the military potential of balloons.

3. David Wallace-Wells on why excess deaths remain high (NYT).

What should I ask Noam Chomsky?

I will be doing a Conversation with him. No need to suggest questions on foreign policy (this is the Conversation I want to have), what else?

Real Return Bonds–Not a Loony Idea

The Canadian government has said it will stop issuing real return bonds, i.e. inflation indexed bonds. Real return bonds are extremely useful to anyone who wants a steady stream of income that keeps up with inflation—retirees, for example. A real return bond would also be ideal for funding an endowment such as a university chair or scholarship program. I agree with John Cochrane and Jon Hartley writing in the G&M that ending sales of these bonds is a bad signal.

So why stop issuing real return bonds? The government may suspect that inflation will go up a lot more, and it will then have to pay more to bondholders. Non-indexed debt can be inflated away if the fiscal situation worsens. The cumulative 11-per-cent inflation since January, 2021, has inflated away 11 per cent of the debt already. Argentines have seen a lot more.

But issuing indexed debt makes sense if the government plans to be responsible. Tax payments and budget costs rise with inflation, and fall with disinflation, so the budget is stabilized if inflation-indexed bond payments do the same. And issuing indexed debt that can’t be inflated away is a good incentive not to turn around and inflate debt away.

Rasheed Griffith on the need for a Caribbean think tank

Worth another link! Here is one bit:

In my opinion, the first priority for a Caribbean think tank or program should be to advocate for the implementation of dollarization, which involves the replacement of all existing Caribbean currencies with the United States Dollar (USD) as the sole currency. This idea is based on the numerous fiscal and monetary shortcomings exhibited by Caribbean governments. The benefit of this proposal is its widespread latent approval and straightforward nature, making it easier to garner support and understanding among the Caribbean people…

The domestic money of Caribbean countries are only useful in the tiny land area of the earth where they are issued. For example, Barbados is 166 square miles and the Barbados Dollar (BBD) only has value in that small space. Why exactly should people be forced to exchange their labour for money that has such a limited use?

You might say that they can easily exchange the Barbados Dollar (BBD) for USD. But that is untrue. Barbados maintains strict capital controls because it cannot allow people to exchange too much BBD for USD as that would cause a crisis for the fixed exchange rate. This is a kafkaesque policy since virtually everything imported into and exported from Barbados is priced and invoiced in USD.

Moreover, the government abuses its position as the issuer of money. Primarily to finance its spendthrift operations by arbitrarily creating new money. This is the evident across the region. In Trinidad & Tobago, the government limited citizens to only a $250 USD allotment for international purchases on credit cards. This forced the black market rate to unprecedented levels, with everyone desperate to acquire USD. It came to a point where some services would give discounts if you pay in USD.

Basic point: Caribbean people are severely disadvantaged by being forced to use money that has no global acceptance. Caribbean governments will perpetually mismanage their domestic money to the detriment of citizens.

The manifesto covers many other issues, interesting throughout.