Facts about Norway

But some worry that a “Norwegian disease” is developing through the use of an ever-increasing withdrawal from the fund each year. That amount — which reached NKr542bn ($54bn) this year — amounts to about a quarter of the government budget.

This year, it helped Norway boost contributions to Ukraine without having to cut spending elsewhere or raise taxes.

Spending on sickness and disability is the highest in the OECD group of rich countries, and four times the average. High-school dropout rates are well above the European average. Meanwhile, productivity growth has slowed, worrying policymakers.

Here is more from Richard Milne in the FT.

Monday assorted links

1. How Arnold Kling reads with AI.

2. Criticism of the Singaporean educational system.

3. Patrick Collison on the uses of crypto. And Matt Huang on permissionless.

4. GPT-5 on Huemer and immortality. And more.

5. How about Chinese stablecoins? (NYT)

6. Milei’s party loses in the elections.

7. How much do AIs push back against psychosis?

8. The Oakland B’s will experiment with being managed by AI (NYT).

9. Good Khodorkovsky thread on Ukraine, Russia, and the war.

Patrick Collison on the Irish Enlightenment

Most of all, the Irish Enlightenment seems to me an instance of small group theory. I’m fond of the thought that between great man and structuralist theories of history there lies an intermediate position: the small group, a colocated cauldron for iconoclastic thinking, can as a collective pioneer a novel direction. The romantics in Jena, the founders of Silicon Valley, the musicians behind punk. Unsurprisingly, the early Irish thinkers are closely connected. Swift and Berkeley attended the same school and were good friends. Hutcheson and Berkeley debated publicly, while Burke’s work is clearly downstream of Hutcheson’s.

And this:

How should we view the movement as a whole? Well, the timing is important: Cantillon published his Essai in 1755, Swift Drapier’s Letters in 1724, and Berkeley The Querist in 1735. It seems to me that, before 1750, the Irish thinkers have a strong claim to leading the world in the field of economics and to having collectively sketched out much of the core of the field in broadly correct terms. In Petty you have economic statistics; in Cantillon you have risk, market pricing, and much else; in Berkeley, you have a theory of national banking plus development economics; in Swift you have proto-monetarism. The claim is not that they figured everything out or were right on all points, but which other school or group could you rank ahead of them? Smith published Wealth of Nations in 1776 and The French physiocrats, who were very important, came later: Quesnay’s first piece wasn’t published until 1756.

Do read the whole short essay.

France fact of the day

If nothing is done, interest payments will become the biggest expense in the French budget in four years, Mr. Bayrou has warned.

Here is the full NYT article, noting that government spending is 57 percent of the economy and the French have the longest financed retirements ever seen in the history of the world.

Eli Dourado on trains and abundance

One thing I got a bit of crap for in the hallways of the Abundance conference is my not infrequent mockery of trains on Twitter. I’m sorry, trains are not an abundance technology. I think many people in the abundance scene like trains because:

1. America’s inability to build HSR is the leading example of low state capacity, and we all more or less agree that state capacity is a tenet of the abundance agenda.

2. Trains have high transport efficiency, and people coming to abundance out of the climate movement can’t shake their old habits of caring about energy efficiency ahead of other considerations.

Obviously if we spend billions of dollars on high-speed rail, there should at least be some high-speed rail service. But a deeper element of state capacity is not picking dumb things for the state to build in the first place. And trains are a dumb thing to build in the 21st century.

A true transportation abundance agenda has to revolve around airplanes and autonomous vehicles. The goal should be able to go from any point in the country to any other point in the country in, like, two hours, door to door.

We should have supersonic airplanes made out of cheap titanium and powered by electro-LCH4. An autonomous vehicle should be available to pick you up within 30 seconds and whisk you to a nearby airfield. Security should be painless and instant (another state capacity task). If your trip doesn’t require an airplane, the autonomous vehicle should get you straight there at 100+ mph since it’s good at avoiding accidents. In cities, autonomous buses with dynamic route planning based on riders’ actual needs beat subways’ 1-dimensional tracks.

We should not be trying to build marginally better versions of 20th century (or 19th century!) technology. We should be more ambitious than that. Trains are unbefitting of a country as wealthy as I aspire for us to be.

Please join the anti-train faction of the abundance movement.

Here is the link to the tweet.

Sunday assorted links

What the financial regulators are saying and feeling

1. “Yes, we know stablecoins will have one hundred percent reserves, but we are not sure we can regulate that system into a position of safety.”

2. “Well, the rest of the financial system has nothing like one hundred percent reserves, but don’t worry we have everything there under control.”

The hole is large enough to drive a truck through. Keep this contrast in mind, because you will be hearing it, expressed in other terms of course, hundreds of times over the next year or so.

The business of birding

You cannot really trust economic impact studies, but still they give a rough sense of orders of magnitude:

Birding is a growing hobby nationwide, especially since the pandemic—and as in Ohio, U.S. birders are an impressive economic force, according to the latest federal data.

A November 2024 report from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) reflects staggering numbers: There are an estimated 96 million birders in the United States—more than a third of U.S. adults—who together spent more than $107 billion in 2022. In total, that’s more money than the 2022 gross domestic product of New Hampshire (and 10 other U.S. states). Those dollars purchased equipment such as binoculars, feeders, and cameras, funded hobby-related trips, and covered other costs large and small, such as plant purchases, subscriptions, field guides, and campers. They also supported 1.4 million jobs and generated billions more in local, state, and federal tax revenue.

…“I was expecting to see expenditures in the billions, but did not expect it to amount to more than $100 billion,” says Tobias Schwoerer, an applied economist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. In a separate study, he and his coauthor, former Audubon Alaska executive director Natalie Dawson, found that birders spent nearly $400 million a year and supported thousands of jobs in Alaska alone.

Here is the full piece. Via Holly Cowen.

Three accounts of modern liberalism

I have a review essay on that topic in the latest TLS. Excerpt, on Philip Pilkington:

Pilkington’s sense of numbers, history and magnitude is sometimes off. He writes that “liberalism is forming broken, atomized people who are unable to pass on their genes to a future generation”, apparently oblivious to the fact that fertility rates are falling in many non- liberal countries as well – in Russia, for example – where they are lower than in the US. In China, fertility is lower still. Is the liberal goal really to “replac[e] the family with the state”? That sounds more like the non-liberal visions we find in western thought, running from Plato to the more extreme forms of communism in which children are encouraged to report on the supposed crimes of their parents.

We are told that “deindustrialization eviscerated American industry”, yet US manufacturing output is now barely below its pre-financial crisis peak, and service sector jobs tend to pay more on average today than do manufacturing jobs. Pilkington also promotes strange theories of trade imbalances, as presented by the non-economists Oren Cass and Michael Pettis but rejected by virtually all serious researchers in the area. Their view is that a huge economic restructuring is needed because China and Germany keep running trade surpluses while the US is in perpetual trade deficit. But in reality this arrangement seems as stable as any other macroeconomic state of affairs could be. It is Pilkington’s prerogative to disagree with the consensus, but we are never told why everyone else might be wrong. Overall, there is too much sloppiness here in service of the agenda of carping about liberal societies.

And on Robert Kagan:

An alternative and less neat vision of American history shows how liberalism has often relied on illiberalism, and not just accidentally. Lincoln was a significant abuser of civil rights, including on habeas corpus. The North’s campaigns in the Civil War killed many thousands of innocent civilians, not all of them in the service of legitimate military ends. You can argue that this may have been necessary, but liberal it was not. As for FDR, he tried to pack the Supreme Court and sought a significant expansion of executive power, making his administrations a methodological precursor of Trump. He did fight the Second World War on the side of liberalism, but he did not always use liberal means (eg the firebombing of Tokyo), and indeed a full respect for the laws of warfare might not have secured victory.

Once we see American history as a union of liberal and illiberal forces, we can relax a little about the current situation. Certainly, we are returning to some bad and illiberal behaviours of the past, and it is right to be concerned. Yet this seems to be more a feature of the ebb and flow of American politics than a decisive turn away from liberalism. Illiberalism has been prominent in the mix most of the time, and that is both the good news and the bad.

Interesting throughout, recommended, I believe it is the Sept.1 issue.

Saturday assorted links

1. Hungarian political evolution?

2. John Horton simulates referee reviews.

3. San Francisco pays squatters to move out, but many do not accept the offer.

4. Emily Linge sings Queen. She is only seventeen, quite a marvel. And doing For No One.

5. The current state of arts funding under Trump.

6. The Metropolitan Opera will raise money by doing Saudi tours (NYT).

Moving on Up

James Heckman and Sadegh Eshaghnia have launched a broadside in the WSJ against the Chetty-Hendren paper The Impacts of Neighborhoods on Intergenerational Mobility I: Childhood Exposure Effects. It’s a little odd to see this in the WSJ but since the Chetty-Hendren paper has been widely reported in the media, I suppose this is fair game. Recall the basic upshot of Chetty-Hendren is that neighborhoods matter and in particular

…the outcomes of children whose families move to a better neighborhood—as measured by the outcomes of children already living there—improve linearly in proportion to the amount of time they spend growing up in that area, at a rate of approximately 4% per year of exposure.

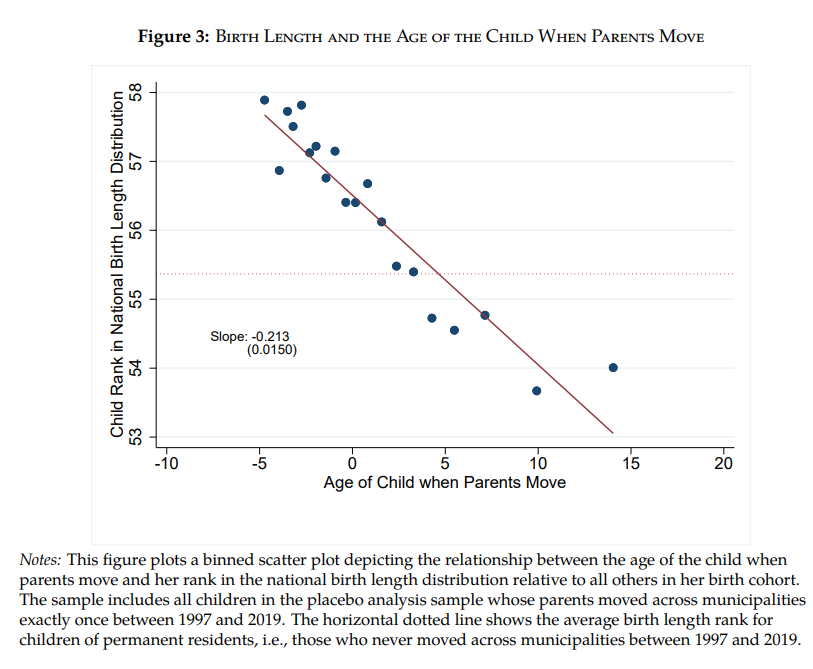

I am not going to referee this dispute but I did enjoy the audacity of one placebo test run by Eshaghnia. Eshaghnia runs the same statistical models as Chetty-Hendren but substitutes birth length (“the distance between a newborn’s head and heels”) instead of adult earnings and college attendance rates. Now, obviously, moving cannot affect birth length! Yet, Eshaghnia finds, in essence*, that children of parents who move to taller neighborhoods have taller children, in parallel with CH who find that children of parents who move to higher income neighborhoods have higher income children. Moreover, the covariance is stronger the earlier parents move. Since birth length is correlated with cognitive abilities and other later life outcomes this is highly suggestive that CH are not finding (pure) causal effects.

* I have simplified slightly for intuition. Technically, Eshaghnia shows that children’s birth‑length ranks align with the destination–origin permanent‑resident birth‑length difference, and that alignment is ≈0.044 stronger for each year earlier the move.

Addendum: Chetty et al. do not find similar results in California (see in particular Figure 2).

A few remarks on Fed independence

Trump has made various sallies against the idea of an independent Fed, including lots of rhetoric, firing Lisa Cook, aiming to have a CEA chair on the Fed board, and more. Probably the list is longer than I realize.

To be clear, I see no upside to these moves and I do not favor them. That said, I am not surprised that markets are not freaking out.

People, the Fed was never that independent to begin with!

Come 2008, the Fed, Treasury, and other parties sat down and worked out a strategy for dealing with the financial crisis. The Fed has a big voice in those decisions, but ultimately has to go along with the general agreement.

Circa, 2020-2021, with the pandemic, the same kind of procedure applied.

You may or may not like the particular decisions that were made (too little inflation the first time, too much inflation the second time), but I don’t think there is a very different way to proceed in those situations.

And given recent budgeting decisions, fiscal dominance may lie in our future in any case. The Fed is not immune from those pressures.

The Fed is most “independent” when the stakes are low and most people are happy with (more or less) two percent inflation. That is also when the independence matters least.

The real problem comes when the quality of governance is low. Then encroaching on central bank independence simply raises the level of stupidity. Some of that is happening right now.

A non-independent central bank can work just fine when the quality of government is sufficiently high. New Zealand has had a non-independent central bank since the Reserve Bank Act of 1989 (before that it had a non-independent central bank in a different and worse way). There is operational independence, but an inflation target is set in conjunction with the government. You may or may not favor this approach, but it has not been a disaster and it helped to lower Kiwi inflation rates significantly and with political cover.

Way back when, Milton Friedman used to argue periodically that Congress should set the rate of price inflation and take responsibility for it. I think that is a bad idea, especially today, but it should cure you of the notion that “independence” is sacrosanct. Every system has some means of accountability built in, and indeed has to.

I know all those scatter plot graphs that correlate central bank independence with lower inflation rates. In my view, if you could insert a true “quality of government” extra variable, the correlation mostly vanishes. Plus I do not trust the measures of independence that are used.

As Gandhi once said — “Central bank independence, it would be a good idea!”

Addendum: I also find it a little strange that many critics of the Trump actions earlier had been calling for higher inflation targets, say three or even four percent. That is maybe not an outright contradiction, but…the Fed isn’t just going to move to that on its own, right? Central bank independence for thee but not for me?

*Take a Girl Like You*, by Kingsley Amis

This excellent and neglected novel deserves a new look in our time. As Christian Lorentzen points out in his useful introduction, if you are interested in (non-Submission) Houellebecq, this is the next place to go. How exactly did we get on the Houellebecq sexual emptiness path to begin with? This novel was published in 1960, and it shows the first steps toward the sexual revolution and the rise of more open sexual competition, with a nod in the direction of what the final results are going to be.

In the novel the old sexual world is still there, and largely in control. There is a distinction between “good girls” and “bad girls,” for instance, or if you are traveling with an opposite sex companion there needs to be talk of “separate bedrooms.” But the characters discuss birth control, and one asks the other why don’t they just…do it? The novel shows how the older world started to break down and morph into what was to come later.

I will not spoil the ending for you.

Interesting and insigthful passages abound. For instance:

“He’s got a sensual face. But he doesn’t know much about women, I think. He talks all the time, and this isn’t necessary, as we women soon learn.”

Or:

He kissed her very thoroughly, without trying to do anything else, and indeed without any of the toiling and moiling, let alone the moaning and groaning, gone in for by the too-serious ones, and/or the ones who put up a show of being serious.

pp.169-171 have the best analysis of “lookism” I have seen.

Amis understands the slippery slope phenomenon very well. He even suggests that greater promiscuity is bound to lead to regularly bisexual women.

Recommended, an easy and fun read, and if it helps you norm my evaluation I did not love Lucky Jim by him.

Tariff sentences to ponder

Trump’s tariff policy is an agenda for pushing American output down the value chain, away from advanced manufacturing and toward making cheaper simpler goods and supplying raw materials to China.

That is from Matt Yglesias.

Friday assorted links

1. An alternate model for training economists?

2. RIP Luis Fernando Verissimo. Borges and the Eternal Orangutans is a very fun book for me.

3. Chinese guy builds Cat World, Department of Why Not?

4. “Walking Tall?” (NYT). The husband did it.

5. AI progressed more quickly than superforecasters had expected. Green energy did not.