Decker and KingoftheCoast on single payer health insurance

Here is the conclusion of the piece:

To reiterate, the key point in this piece is that high administrative costs in US healthcare are unlikely to represent “do-nothing waste.” Some of the purported costs are entirely fake. To include them in the possible savings of single payer shows either ignorance or dishonesty. Some of the costs are to prevent waste and fraud, which should be paid by Medicare now (although they are not). Of what is left, the cost of duplication pales in comparison to the plausible benefits of choice and competition in health insurance. When you put all of these together, the case for single-payer is nonexistent. A better system would be to subsidize those who are too poor to pay, scrap the government health insurance providers and the VA, remove the employer tax deduction, and allow providers to compete.

Here is the full piece, excellent work.

Wednesday assorted links

Singapore’s Pay Model Isn’t India’s: Market Wages vs. Civil-Service Rents

In my post How High Government Pay Wastes Talent and Drains Productivity I pointed to evidence that high government compensation in poorer countries creates tremendous waste and drains the private sector of productive talent. A reader asked: What about Singapore?—famous for paying its top officials very well.

Singapore, however, is hardly comparable to India. Its GDP per capita is about 37 times India’s (~$91k vs. $2.4k) and its population is ~1/233rd the size (6m vs. 1.4b). Still, lets take a closer look.

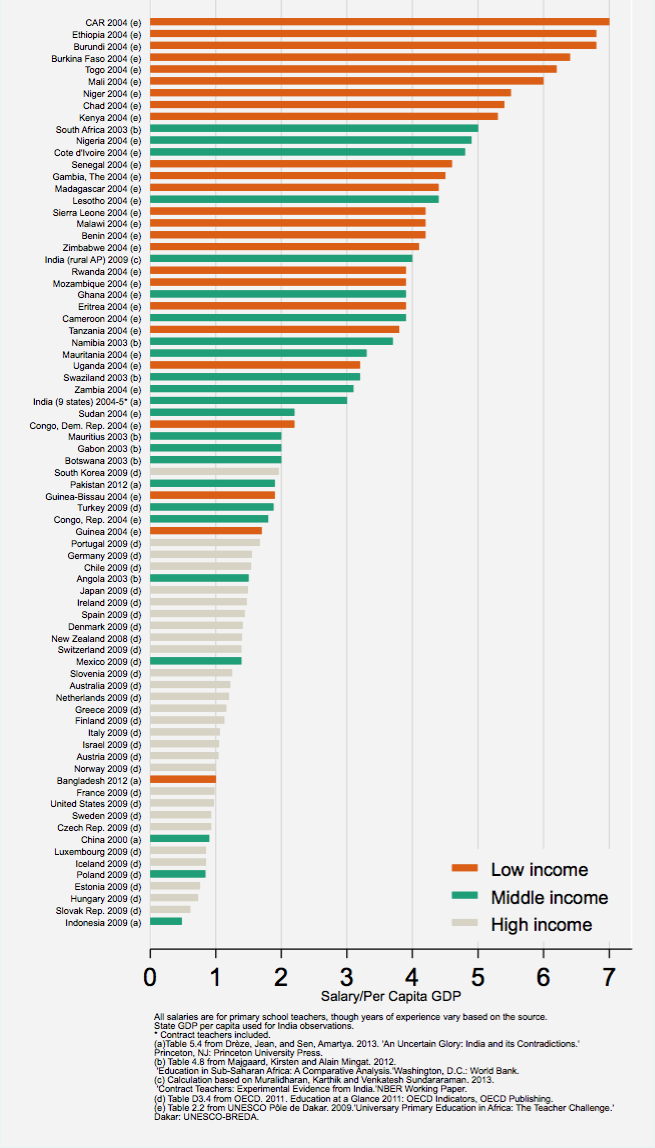

When I discuss high public pay in places like India, Greece, or Brazil, I don’t mean a few top ministers. I mean millions of railway clerks, office staff, and civil servants. Teachers illustrate the point well, since their work is broadly similar worldwide. As Justin Sandefur shows in the data at right, teacher salaries relative to GDP per capita tend to be highest in the poorest countries—sometimes five times GDP per capita or more.

Sandefur comments:

This may come as a bit of a surprise to many rich-country readers. There’s no doubt that teachers in, say, India earn much less than teachers in Ireland, but relative to context, they tend to be very well paid. Dividing by per capita GDP is a rough and ready way to put salaries in context.

The evidence suggests supply and demand can’t explain this. For example, in countries where teachers are highly paid relative to GDP per capita, they’re also paid far above private-sector wages for the same job. Sandefur presents more evidence on this question and concludes:

…Public school teachers in many developing countries earn civil service salaries that are far higher than market wages. This is what economists traditionally refer to as “rents.”

Singapore does NOT fit this pattern. Its teachers earn on the order of 70–80% of GDP per capita, market wages, not inflated packages. What’s unusual in Singapore is only at the top: a small number (fewer than 500) of elite officials and politicians have salaries pegged to the highest 1,000 Singapore-citizen income earners.

The issue Singapore is tackling is wage compression. In many democracies, collective bargaining combined with fairness, envy and inequality concerns pushes pay up at the bottom and down at the top. Denmark and heavily unionized firms are classic cases. Singapore, meritocratic and unapologetic, instead says its highest-ranking officials should be paid like CEOs.

Unlike India, Italy, Greece or Brazil, Singapore’s policy is not to pay any government workers above market wages but to pay competitive salaries to its entire civil service, even those at the top. Crucially, Singapore does not use mass exams to limit entry–it doesn’t have to because by keeping wages consistent with similar jobs in the private sector it matches supply to demand. As a result, we do not see in Singapore thousands or even millions of over-qualified people applying for a handful of over-paid government jobs, as in this example from Italy (quoted in Geromichalos and Kospentaris):

Italy’s chronic unemployment problem has been thrown into sharp relief after 85,000 people applied for 30 jobs at a bank [. . . ] The work is not glamorous – one duty is feeding cash into machines that can distinguish banknotes that are counterfeit or so worn out that they should no longer be in circulation. The Bank of Italy whittled down the applicants to a “shortlist” of 8,000, all of them first-class graduates with a solid academic record behind them. They will have to sit a gruelling examination in which they will be tested on statistics, mathematics, economics and English [. . . ] The high level of interest was a reflection of the state of the economy but also of the Italian obsession with securing “un posto fisso” – a permanent job.

So far from being a counter-example, Singapore illustrates the lesson: Singapore pays market wages, not rents—thereby avoiding the rent-seeking and talent misallocation that plague countries where civil servants are paid far above their market value.

My biographical podcast with Joshua Rosen

Joshua writes me:

It came out great.

Here it is on Apple: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/formative-figures/id1809832335?i=1000723588104

Here it is on Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/episode/5q5rnjcQTLASL438hI6s3c?si=YWB2sduVRmiCV0TUrSRSHg

Lots of fun for me, mostly tales of childhood and the like.

Do not forget

Estimating real-world vaccine effectiveness is vital to assessing the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination program and informing the ongoing policy response. However, estimating vaccine effectiveness using observational data is inherently challenging because of the nonrandomized design and potential for unmeasured confounding. We used a regression discontinuity design to estimate vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 mortality in England using the fact that people aged 80 years or older were prioritized for the vaccine rollout. The prioritization led to a large discrepancy in vaccination rates among people aged 80–84 years compared with those aged 75–79 at the beginning of the vaccination campaign. We found a corresponding difference in COVID-19 mortality but not in non-COVID-19 mortality, suggesting that our approach appropriately addressed the issue of unmeasured confounding factors. Our results suggest that the first vaccine dose reduced the risk of COVID-19 death by 52.6% (95% confidence limits: 15.7, 73.4) in those aged 80 years, supporting existing evidence that a first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine had a strong protective effect against COVID-19 mortality in older adults. The regression discontinuity model’s estimate of vaccine effectiveness is only slightly lower than those of previously published studies using different methods, suggesting that these estimates are unlikely to be substantially affected by unmeasured confounding factors.

From Charlotte Bermingham, et.al. There is plenty of other research yielding broadly similar conclusions. The Covid vaccines saved millions of lives, well over two million lives even from a conservative estimate.

For the pointer I thank Alex T.

Tuesday assorted links

1. “Almost everything is downstream of integrity.“

2. Two Edward Yang movies have been released by Criterion.

3. Massive haboob near Chandler, Arizona!

4. South Korean police hologram lowers crime?

5. Some points on the Lisa Cook firing. That said, I agree with Phil Magness. It was a mistake to appoint her in the first place, but given the current context it was bad to fire her as well. And here is David Beckworth. Here is Kalshi.

Is AI making it harder to enter the labor market?

There are new results from Erik Brynjolfsson, Bharat Chandar, and Ruyu Chen:

This paper examines changes in the labor market for occupations exposed to generative artificial intelligence using high-frequency administrative data from the largest payroll software provider in the United States. We present six facts that characterize these shifts. We find that since the widespread adoption of generative AI, early-career workers (ages 22-25) in the most AI-exposed occupations have experienced a 13 percent relative decline in employment even after controlling for firm-level shocks. In contrast, employment for workers in less exposed fields and more experienced workers in the same occupations has remained stable or continued to grow. We also find that adjustments occur primarily through employment rather than compensation. Furthermore, employment declines are concentrated in occupations where AI is more likely to automate, rather than augment, human labor. Our results are robust to alternative explanations, such as excluding technology-related firms and excluding occupations amenable to remote work. These six facts provide early, large-scale evidence consistent with the hypothesis that the AI revolution is beginning to have a significant and disproportionate impact on entry-level workers in the American labor market.

Here is WSJ coverage from Justin Lahart.

David Splinter on how much tax billionaires pay

Here is his comment on the paper presented here:

Summary: The U.S. tax system is highly progressive. Effective tax rates increase from 2% for the bottom quintile of income to 45% for the top hundredth of one percent. But rates may be lower among those with the highest wealth. This comment starts with the “top 400” tax rate estimates by wealth in Balkir, Saez, Yagan, and Zucman (2025, BSYZ), and adjusts these to account for Forbes family wealth being spread across multiple tax returns, to avoid double-counting capital income, to include missing taxes, and to apply standard tax and income definitions. This results in “top 400” effective tax rates exceeding overall tax rates by 13 percentage points. Still, the “top 400” tax rate is lower than for the top hundredth of one percent, suggesting a modest decline in effective tax rates at the very top when ranking by wealth. However, this is an unsurprising deviation from progressive rates because the tax system targets income, not wealth. Compared to the annual estimates in BSYZ, longer-run estimates are more appropriate for top wealth groups, which have volatile wealth and concentrate charitable giving into end-of-life bequests. End-of-life giving suggests long-run top 400 effective tax-and-giving rates could exceed 75%.

USA counterfactual estimate of the day

With zero net immigration, Apollo Chief Economist Torsten Slok estimates, the U.S. economy would be able to sustainably add only about 24,000 nonfarm jobs a month, compared with an average 155,000 from 2015 through 2024.

Here is the full WSJ article. It really helps an economy to have both aggregate supply and aggregate demand increasing at the same time.

How Much Tax Do US Billionaires Pay?

We estimate income and taxes for the wealthiest group of US households by matching Forbes 400 data to the individual, business, estate, and gift tax returns of the corresponding group in 2010–2020. In our benchmark estimate, the total effective tax rate—all taxes paid relative to economic income—of the top 0.0002% (approximately the “top 400”) averaged 24% in 2018–2020 compared with 30% for the full population and 45% for top labor income earners. This lower total effective tax rate on the wealthiest is substantially driven by low taxable individual income relative to economic income. First, the C-corporations owned by the wealthiest distributed relatively little in dividends, limiting their individual income tax unless they sell their stocks. Second, top-owned passthrough businesses reported negative taxable income on average in spite of positive book income, further limiting their individual income tax. The top-400 effective tax rate fell from 30% in 2010–2017 to 24% in 2018–2020, explained both by a smaller share of business income being taxed and by that income being subject to lower tax rates. Estate and gift taxes contributed relatively little to their effective tax rate. Top-400 decedents paid 0.8% of their wealth in estate tax when married and 7% when single. Annual charitable contributions equalled 0.6% of wealth and 11% of economic income in 2018–20.

That is from a new NBER working paper by

Addendum: Here is a comment from David Splinter.

How Retrainable are AI-Exposed Workers?

We document the extent to which workers in AI-exposed occupations can successfully retrain for AI-intensive work. We assemble a new workforce development dataset spanning over 1.6 million job training participation spells from all US Workforce Investment and Opportunity Act programs from 2012–2023 linked with occupational measures of AI exposure. Using earnings records observed before and after training, we compare high AI exposure trainees to a matched sample of similar workers who only received job search assistance. We find that AI-exposed workers have high earnings returns from training that are only 25% lower than the returns for low AI exposure workers. However, training participants who target AI-intensive occupations face a penalty for doing so, with 29% lower returns than AI-exposed workers pursuing more general training. We estimate that between 25% to 40% of occupations are “AI retrainable” as measured by its workers receiving higher pay for moving to more AI-intensive occupations—a large magnitude given the relatively low-income sample of displaced workers. Positive earnings returns in all groups are driven by the most recent years when labor markets were tightest, suggesting training programs may have stronger signal value when firms reach deeper into the skill market.

That is from a new NBER working paper by

Monday assorted links

1. Some economics of AI subscription pricing.

2. “Cat food made by Michelin star chef is on sale… and people think it’s delicious.”

3. Is video to blame for gender polarization?

4. Those new service sector jobs?

5. “An innovative contest by a city in formerly communist east Germany to curb depopulation by offering a fortnight of free housing has stunned local officials with its success.” Link here.

6. Benjamin Yeoh visits Accra.

7. Banks are making a regulatory pushback against stablecoins (FT).

Is religion actually declining in emerging economies?

Building on large-scale survey data and recent scholarship, we document persistent and, in many regions, increasing levels of religiosity…we analyze the determinants and consequences of religious behavior, showing how income volatility, financial insecurity, and cultural transitions sustain demand for religion. Third, we explore the institutional and political dimensions of religion in EDCs, emphasizing the role of religious institutions as public goods providers and as politically influential actors. This discussion offers a framework for understanding religious organizations as adaptive, competing platforms in pluralistic religious marketplaces. Overall, our findings suggest that religious adaptation, rather than decline, is central to understanding the future of religion and its economic implications in the developing world.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Sara Lowes, Benjamin Marx, and Eduardo Montero.

India, Greece, Brazil: How High Government Pay Wastes Talent and Drains Productivity

Compensation for government jobs is higher relative to GDP per capita the poorer the country. In other words, government workers are most overpaid in poor countries. Excessive public-sector compensation in low- and middle-income countries distorts labor markets on two margins: queues (rent-seeking to win jobs) and misallocation (talent and taxes diverted from the private sector).

In my two posts Massive Rent-Seeking in India’s Government Job Examination System and The Tragedy of India’s Government-Job Prep Towns I drew attention to the first margin, rent-seeking losses from the queues. India’s most educated young people—precisely those it needs in the workforce—often devote years of their life cramming for government exams instead of working productively. These exams cultivate no real-world skills and entire towns have become specialized in exam preparation. I argued using a back-of-the-envelope calculation that the rent seeking losses alone could easily be on the order of 1.4% of GDP annually. More tragically, large numbers of educated young people are inevitably disillusioned. Finally, because pay is so high, the state can’t staff up; India has all the laws of a rich country with roughly one‑fifth the civil servants per capita.

Two macro papers quantify the other margin of loss: who ends up where.

In The unintended consequences of meritocratic government hiring, Geromichalos and Kospentaris (GK) look at the consequences of excessively high government salaries in Greece. In (MIS)Allocation Effects of an Overpaid Public Sector, Cavalcanti and Santos look at the case of Brazil. Both papers model the allocation of labor between the private and public sectors and focus on the cost of drawing too many high-productivity workers into government jobs.

GK summarize their results for Greece:

In many countries, public employees enjoy considerable job security and generous compensation schemes; as a result, many talented workers choose to work for the public sector, which deprives the private sector of productive potential employees. This, in turn, reduces firms’ incentives to create jobs, increases unemployment, and lowers GDP…. [Calibrating the model to Greece] we find that a 10% drop in public sector wages results in a 3.8% increase in private sector’s productivity, a 7.3% drop in unemployment, and a 1.3% increase in GDP.

CS report similar distortions in Brazil:

Our counterfactual exercises demonstrate that public–private earnings premium can generate important allocation effects and sizeable productivity losses. For instance, a reform that would decrease the public–private wage premium from its benchmark value of 19% to 15% and would align the pension of public sector workers with the one in place for private sector workers could increase aggregate output by 11.2% in the long run without any decrease in the supply of public infrastructure.

Interestingly, in the GK model there is no rent-seeking waste because workers are assumed to forecast exam outcomes perfectly and sort directly into private or public streams. In my India model, by contrast, the waste comes precisely from the years of futile exam preparation. GK also find that reducing the number of public jobs can raise efficiency, while my take is that in India high salaries make the public sector paradoxically too small (thus to some extent limiting misallocation). CS also focus on allocation but, unlike GK, they estimate that rent-seeking losses are massive—about triple my conservative estimate:

The aggregate cost of job applications to public jobs, which we label as the rent seeking cost, is large in the baseline economy…roughly 3.61 percent of output.

Across India, Greece, and Brazil the story converges: overpaying government workers distorts education, job search, and firm dynamics. The waste shows up as socially unproductive effort devoted to entering the echelons of government employment and a private sector which is drained of top talent causing it to be less productive and to grow more slowly. In short, rent seeking and misallocation from overly generous government compensation generate large macroeconomic losses. As relative compensation tends to be higher the poorer the economy, high government pay can be a development trap.

What I’ve been reading

David Woodman, The First King of England: Aethelstan and the Birth of a Kingdom. An excellent work. One of the best books on early English history, and also one of the best books on how the Dark Ages morphed into early Medieval times. Usually I find treatments in both areas difficult to follow, but this one produces a coherent and also non-exaggerated narrative. It also will make you want to visit Northumbria.

Edmund Phelps, My Journeys in Economic Theory. A fascinating memoir, I had not known he was so obsessed with Rawls and Nagel. He also loved the tenor Franco Corelli, and was a Birgit Nilsson fan too. Recommended, for those who like this sort of thing, and who already are familiar with the cast of characters.

Bench Ansfield, Born in Flames: The Business of Arson and the Remaking of the American City. Whenever a book demonstrates what people in New Jersey have known for decades, usually it is a good book.

Andrew Sean Greer, Less: A Novel. I do not like much in contemporary American fiction, but so far I am quite enjoying this one.

Bernd Roeck, The World at First Light: A New History of the Renaissance. 934 pp. of text, covers too many topics in too desultory a fashion?

Pablo A. Pena, Human Capital for Humans: An Accessible Introduction to the Economic Science of the People, is a good popular-level introduction to human capital theory.

There is Carl Benedikt Frey, How Progress Ends: Technology, Innovation, and the Fate of Nations.