Results for “food” 2039 found

How to find good food in Chengdu

1. Many people in Chengdu are experts on the local food scene. Recruit one of them, but don’t be shocked if they insist on paying for your meal every time.

2. Go downtown to the Crowne Plaza hotel, walk out on the main road to your left, and within two minutes you will see on your left a “TangSong food street” — a covered food court about twenty-five small Sichuan places. There is a sushi place too but I saw the customers dipping their sushi rolls in hot red chili oil. It is heartwarming to walk into such a culinary universe.

2b. Within this court my favorite place is labeled “1862 History,” you might spot the small print, in any case the place looks spare and is somewhat larger than the very small venues.

3. MaPo tofu is much finer here, and the black peppers and quality vinegars are to be appreciated.

4. Sichuan chili chicken and Dan Dan noodles are two of my favorite Sichuan dishes back home. Here they have been good, but actually slightly disappointing relative to expectations. Don’t obsess over those during your quest.

4b. There are two philosophies of international trade. In one philosophy, the best dishes are the best dishes and so you should order them at home and also order them abroad in their countries of origin. In the second philosophy, it is the most exportable dishes which get exported but they are not in general the best dishes period. When abroad you therefore should try out the dishes you cannot find at home. For Chengdu at least, this second philosophy is the correct one as Jacob Viner had hinted way back in the mid-1930s.

5. Often the most interesting dishes are the accompanying vegetables. For instance at a hot pot restaurant I had excellent elongated yam cubes coated in a (slightly sweet) blueberry sauce and stacked ever so perfectly. It was the ideal offset to the hotness and tingle of the core dishes. At another restaurant I most enjoyed some simple greens dipped in a sesame soy sauce. Or try potato or lotus root in hot pot.

6. Unless you go to great lengths to avoid this fate, you will end up eating strange parts of the animal. You won’t like all of them, but you won’t dislike all of them either.

6b. If you utter “Ma La” with conviction, they will think you are remarkably sophisticated or perhaps even fluent in Chinese. The populace here seems unaware that some version of real Sichuan food is now reasonably popular in the United States.

7. Many menus have photos, but they show lots of red and are not useful for identifying exactly what you will be eating. See #6.

8. There are two areas — Jin Li and Wenshu Fang — where old buildings and streets are recreated and you can stroll in a kind of outdoor shopping mall. Everyone goes to these locales and they are fun. These neighborhoods are good for finding lots of takeaway Sichuan snacks, including desserts, in a single area, and served in sanitary conditions. That said, I don’t think these are the very best Sichuan goodies to be had in town, as they are designed explicitly for tourists, albeit food-loving Chinese tourists.

9. “Chengdu food” and “Sichuan food” are not the same thing. Sichuan province has more people than France, and Chengdu is simply one large city, and so your favorite Sichuan dish may not be a staple here. The town also has a fair amount of Tibetan food, though I haven’t tried any.

10. If you leave Chengdu confused as to exactly where and what you ate, you probably had a very good food trip.

*The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu*

That is the new and excellent book by Dan Jurafsky, due out this September, and I found it interesting throughout. Here is just one bit:

In fact, the more Yelp reviewers mention dessert, the more they like the restaurant. Reviewers who don’t mention a dessert give the restaurants an average review score of 3.6 (out of 5). But reviewers who mention a dessert in their review give a higher average review score, 3.9 out of 5. And when people do talk about dessert, the more times they mention dessert in the review, the higher the rating they give to the restaurant.

This positivity of reviews, filled with metaphors of sex and dessert, turns out to be astonishingly strong.

That is another reason not to trust customer-generated restaurant reviews.

And how exactly do Americans conceive of dessert?

Americans usually describe desserts as soft or dripping wet…US commercials emphasize tender, gooey, rich, creamy food, and associate softness and dripping sweetness with sensual hedonism and pleasure.

This association between soft, sticky things and pleasure isn’t a necessary connection. For example, Strauss found that Korean food commercials emphasize hard, textually stimulating food, using words like wulthung pwulthung hata (solid and bumpy), coalis hata (stinging, stimulating), thok ssota (stinging), and elelhata (spicy to the extent one’s nerves are numbed).

How can you resist a book with sentences such as these?

The pasta and the almond pastry traditions merged in Sicily, resulting in foods with characteristics of both.

Here is a previous MR post on Jurafsky, including a link to his blog, and concerning “Claims about potato chips.”

Should you scorn seafood in the American Midwest?

Bruce Arthur, a loyal MR reader, writes to me:

I grew up in a Polish immigrant neighborhood in Chicago, where I was raised on a diet high in seafood. My mother was raised close to the Baltic Sea and we weekly went to the local grocery store and bought a lot of salmon, halibut, sea bass, and scallops. I thought it was absolutely delicious. Sometimes we went to local ethnic grocery stores (generally Italian, the Italians had lived in the neighborhood before the Poles came and still ran a lot of businesses) and bought fish that was whole rather than filleted.

When I went off to college, I encountered people from the East Coast for the first time in my life, and I was shocked to learn that they did not believe that good seafood could possibly exist far away from an ocean coast. They would say things like “I would never eat fish in the Midwest, I wouldn’t trust it!’, which, as an 18 year old who was very much alive after eating a lot of fish in the Midwest, I found absurd.

After all, I thought, isn’t most seafood globally sourced these days? Few of our common food fishes are actually native to the Atlantic Coast, and if you’re flying fish in from the Pacific Northwest, South America, or Oceania, it seems to me that it should be least fresh on the East Coast, which is the part of America furthest away from where these fish are actually caught.

Of course, there could be other factors. Perhaps fish is freshest not closest to the ocean, but in denser areas – if everything is closer together, the places where fish is bought and eaten are presumably closer to the site of its first arrival in the area. Perhaps there’s a cultural factor: fish wasn’t always globally sourced, so perhaps coastal areas have more fish tradition that results in a higher quality of food. But surely the historic high rate of movement within (and into) America weakens that effect.

Anyway, I’m wondering if you have any insight into this. Am I right to scoff at regional seafood snobs, or do they have a point?

The more important reality is that hardly any regions in the United States have good indigenous seafood these days and thus no relative snobbery is justified. Maine lobster or catfish in parts of the south might be exceptions, and in neither case does the Alchian and Allen theorem hold (i.e., the highest quality goods remain those closest to the source).

In general regional demand effects are strong, as I argue in An Economist Gets Lunch. People outside of southern Ohio don’t understand good Cincinnati chili and so they don’t get it. The ingredients can in fact be transferred to North Carolina but they aren’t, least of all with the proper applications. A lot of good Sichuan dishes can be reproduced reasonably well in the United States, but you don’t get them until the properly demanding clientele is in place (by the way Gourmet Kingdom in Carrboro, NC is excellent). Who amongst us is a properly demanding judge of asam laksa? And so on. One interesting feature of these equilibria is that regional mobility does not seem to undo them. If you move to southern Ohio, you can rather rapidly become a standard bearer of good taste in chili, but you slack off once you are back in northern Virginia.

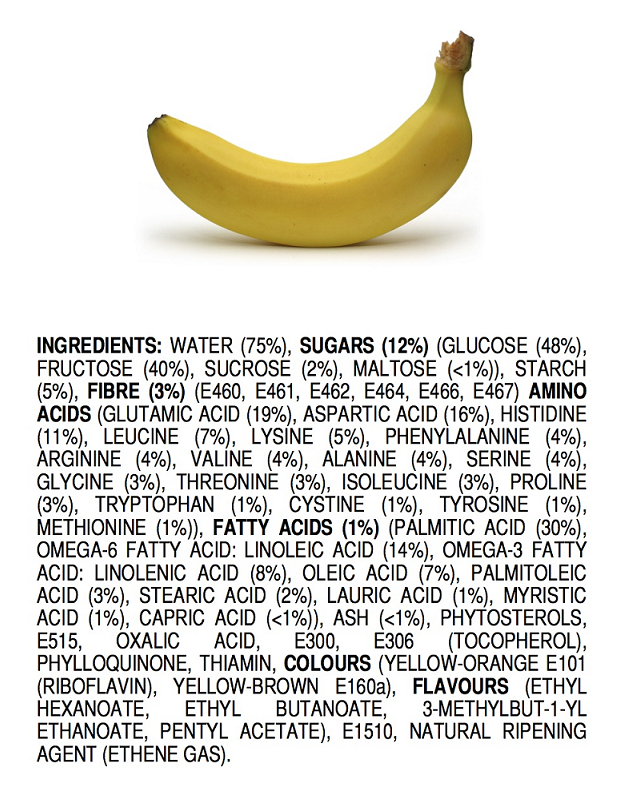

The Chemicals in Our Food

More here.

Do Americans prefer hand-held foods?

Are there any dishes or foods that you would classify as typically, or even exclusively, “American?”

A number of iconic foods—hot dogs and hamburgers, snack food—are hand-held. They’re novelties associated with entertainment. These are the kinds of food you eat at the ballpark, buy at a fair and eventually eat in your home. I think that there is a pattern there of iconic foods being quick and hand-held that speaks to the pace of American life, and also speaks to freedom. You’re free from the injunctions of Victorian manners and having to eat with a fork and knife and hold them properly, sit at the table and sit up straight and have your napkin properly placed. These foods shirk all that. There’s a sense of independence and a celebration of childhood in some of those foods, and we value that informality, the freedom and the fun that is associated with them.

“But we just had Indian food yesterday!”

I’ve never understood this argument, which is sometimes cited as a reason to go to a non-Indian restaurant on a given day. How should people cope who live in India? They have Indian food many, many days in a row, and often (not always, by any means) poorer Indians are choosing from a less varied menu of that food than Americans who visit Indian restaurants. Would it be so terrible to eat only Indian food, whether at home or in restaurants, every day for a week? Every day for a month? I don”t see why. So how about two days in a row? Or two meals in a row? Three? What if you had Indo-Chinese food somewhere in the middle of the sequence? Momos cooked by Nepalese immigrants?

Until a group meal yesterday, I had Korean food five days in a row, three meals a day, much to my joy. I bet some Koreans, in Korea, did the same.

From the comments, on the economics of food stamps

In response to my earlier food stamps post, here is Brian Donahue:

Context:

http://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/34snapmonthly.htm

Economic conditions have been improving, grudingly, for three years now. But between October 2010 and October 2013, the cost of the program has risen 25%. I understand the concept of ‘countercyclical stabilizers’. This is something else. The idea of a 10% cut in this context…ok.

Food stamps aren’t being singled out here. Just because entitlement reform is paralyzingly hard, it doesn’t mean we don’t keep moving on the other stuff. Summing up 2013: fiscal cliff tax increases on rich, medicare investment tax on the rich, ending payroll tax holiday, sequester (half defense.) Republicans are playing ball – at some point along the way, food stamps get a look. If a 10% cut here is a sacred cow, we’re not close to having the stomach for the real fights to come.

And here is PLW:

Explaining the Rs food stamp focus is a little more complicated. First of all, labeling the House nutrition title of the Farm Bill as “going after” the program seems unfair. The House food stamp proposals include uncoupling categorical eligibility for food stamps with receipt of a trivial non-cash TANF benefit (a technique used by many states to waive all asset requirements for food stamps and raise the net income test to twice the poverty line), getting rid of a loophole (i.e., “LIHEAP loophole”) that a small number of states in the (primarily in the Northeast) use to artificially reduce the net income of food stamp beneficiaries in order to raise their level of benefits, and taking away the Secretary of USDA’s work requirement waiver authority for non-disabled adults without dependents.

Second (and this is where it gets complicated), many of the policies that the Rs are pushing in the context of the Farm Bill are going after policies that were put in place as direct result or an unintended consequence of other R policies. For instance, the coupling of categorical eligibility to non-TANF cash benefits is the result of the 1996 welfare reforms which ended AFDC (how one used to become categorically eligible for food stamps) in replace of a much less clear TANF benefit (rather than cash linked to AFDC, one might receive a service in the form of a 1-800 hotline for pregnancy prevention linked to TANF), but continued to bestow eligibility for food stamps to the recipients of AFDC’s successor. At the same time, the 2002 Farm Bill streamlined eligibility by creating a number of state options for food stamps with the intention of pacifying the states who were getting penalized for having high food stamp error rates (those same error rates the USDA now brags about) as the result of having more food stamp participants with earned income as the result of the 1996 welfare reforms (i.e., administratively, it’s more difficult to assign benefits to people with earned income rather than unearned income… especially if those low-income people are in and out of work through the course of a month).

The food stamps program

In an ideal policy world, would food stamps exist as a program separate from cash transfers? Probably not. But as it stands today, they are still one of the more efficient programs of the welfare state and the means-testing seems to work relatively well. And giving people food stamps — since almost everyone buys food — is almost as flexible as giving them cash. It doesn’t make sense to go after food stamps, and you can read the recent GOP push here as a sign of weakness, namely that they, beyond upholding the sequester, are unwilling to tackle the more important and more wasteful targets, including Medicare and also defense spending, not to mention farm subsidies. Here are a few basic numbers on when food stamps have grown and what has driven that growth. It has not become a “problem program” in the way that say disability has.

The Japanese food transition

1. Peak “buckwheat noodle” came in 1914.

2. Peak horse meat came in the 1960s.

3. Peak whale meat came in 2005-2006, although some of that supply was frozen and has not yet been consumed.

4. The consumption of vegetables has been broadly constant for decades.

5. Yearly per capita pork consumption has risen from 1.1 kg in 1960 to 11.7 kg in 2008. During the 1960s, the consumption of chicken meat nearly quintupled.

6. In 1876, per capita sake consumption was 17 liters per capita, which was very high for Japanese income at the time. You can compare that to America’s 7 liters of ethanol per drinking age person in 1870.

7. Land area under cultivation peaked in 1921. The United States and China, however, cultivated more land in 2000 than they did in 1900.

8. Japan’s paddy fields peaked in 1969.

9. In 2006 Japanese meat consumption edged out fish consumption for the first time.

All of those estimates are from a very interesting book by Vaclav Smil and Kazuhiko Kobayashi, Japan’s Dietary Transition and Its Impacts.

What is the least known, great food pilgrimage in the United States?

Could it be Hmong Village, 1001 Jackson Parkway, in north St. Paul?

It is a large indoor market, set in a warehouse, Hmong stores and stalls only, a kind of Eden Center (for those of you who know Falls Church, VA) for Laotians. The produce and spice and bark sections are amazing. Along one wall of the warehouse are about fifteen small restaurants, barely more than stalls, mostly Hmong in their cooking but two served authentic-looking Thai food.

Based on visual inspection of the options, we dined at Houaphanh Kitchen, which was superb, don’t forget the dipping sauces. And I hope you like purple sticky rice. The other places did not look much worse and there were many more dishes I wanted to sample. Overall entrees ran in the $4 to $6 range. Highly recommended.

Here is some discussion, with good photos. Here are some useful Yelp reviews.

Indian food price inflation

Vegetable prices in India spiked 46.59% in July year over year, another ugly bullet point in the country’s persistent struggle with massive food inflation.

The longer story is here.

Last week an Indian truck was hijacked for its forty tons of onions. Here are Brendan Greeley and Kartik Goyal on India’s onion price crisis.

By the way, the falling rupee is not helping India’s export performance. The rupee is also creating planning horizon problems for Indian corporations.

Singaporean hawkers are some of the best food creators in the world

From a recent cook-off challenge:

Singapore’s humble but beloved hawkers have triumphed 2-1 in a cook-off with the legendary Gordon Ramsay who runs restaurants that have earned not just one but three Michelin stars. Are our hawkers then worthy of Michelin star attention? Well, they may not be decorated, but it looks like they still win the hearts of locals.

Nearly 5,000 people thronged the Singtel Hawker Heroes Challenge to see the Ramsay, the Hell’s Kitchen star, pit his skills against three hawkers who were chosen in a national poll drawing 2.5 million votes. The chef only had two days to learn and prepare the same hawker food that these local masters have been doing for decades.

There is more detail here, additional coverage here, and it is no surprise Ramsey fell flat on the laksa.

There is, by the way, plenty of talk that the hawkers are an endangered species. With rising rents, various bureaucracies are asking whether the hawker centers really deserve so much dedicated land in the city plans. There’s also a question whether the younger generation wants to take on jobs which are so stressful and demanding, when so many other good jobs are available in Singapore. Other hawker centers are suffering in quality just a wee bit from the gentrification of their neighborhoods. Let’s hope for the best but I fear for the worst.

My Singapore food recommendation, by the way, is the Ghim Moh Market and Food Centre, which has numerous gems and is one of those “pre-upgrade” hawker centers, with a design dating from 1977. (Unfortunately they will close it for renovation next year, which will probably mean the loss of some hawkers.) My favorite dish was the dosa at Heaven’s Indian Curry, arguably the best I have had, including in South India. They open at six a.m. each morning, every single day, see my remarks above. Their dishes cost either one dollar or two dollars (roughly, actually less).

Chicago food bleg

From a loyal MR reader and diner, who has excellent taste in food by the way:

Might you be willing to post another bleg, this one about Chicago? The results from the Toronto one were fabulous (and it also seemed to generate a good conversation among your readers). We’re headed there Saturday, and I’m disappointed so far in my research efforts…

I don’t have a trip scheduled just yet, but I am sure I will benefit from your answers as well. We both thank you in advance.

Why does South Indian food taste better when you eat it with your fingers?

I can think of three reasons.

First, there is a placebo effect. For the Westerner/outsider, eating with your fingers seems exotic. For (many, not all) South Asians, eating with your fingers brings back memories of family and comfort foods.

Second, your fingers are highly versatile and they are often the best implements for consuming these foods and blending together spices, condiments, and foodstuffs themselves. There is a reason why humans evolved fingers rather than forks.

Third, and how shall I put this? A lot of South Indian food is vegetarian and eating with your fingers adds flavors of…meat. The fleshy sort.

Eating a dosa with fork and knife is a very different experience, for Tamil food on the palm leaf all the more so.

Incentive compatibility of food and drink

Authorities in the eastern Indian state of Bihar have ordered headteachers to taste all school lunches before they are served after 23 schoolchildren died eating a lunch contaminated with pesticide.

Amarjeet Sinha, the top official in the local education department, told reporters that cooking oil used at the school in Chapra District, 40 miles from the Bihar state capital of Patna, had been stored in or near a container previous filled with pesticide.

Sinha said notices published on Thursday morning in local newspapers ordering headteachers to taste food and to ensure safe storage of ingredients would “dispel any fear in [children’s] minds that the foods are unsafe.”

Children across Bihar, one of the poorest states in India, have been refusing to eat free school lunches since the incident on Tuesday.

It remains to be seen if this will in any way prove effective. The rest of the story is here, via Joss Delage. I am pleased, by the way, to have arrived in Bangalore.