Does Money Affect Creativity in the History of Western Classical Music?

That is the subtitle of a new paper by Karol J. Borowiecki, Yichu Wang, and Marc T. Law. Here is the abstract:

How do financial constraints affect individual innovation and creativity? Understanding this relationship is essential, especially when innovation and creativity rely on the capacity to take risks. To investigate this, we focus on Western classical composers, a unique group of innovators whose lives offer a rich historical case study. Drawing on biographical data from a large sample of composers who lived between 1750 and 2005, we conduct the first systematic empirical exploration of how composers’ annual incomes correlate with measures of the popularity (as viewed from posterity), significance, and stylistic originality of their music. A key contribution is the development of novel measures of composers’ financial circumstances, derived from their entries within Grove Music Online, a widely used music encyclopedia. We find that financial insecurity is associated with reduced creativity: relative to the sample mean, in low income years, composers’ output is 15.7 percent lower, 50 percent less popular (based on Spotify’s index), and generates 13.9 percent fewer Google search results. These correlations are robust to controlling for factors influencing both income and creativity, with no evidence of pre-trends in creativity prior to low-income years, suggesting that reverse causality is unlikely. Case studies of Mozart, Beethoven, and Liszt show that low income periods coincide with declines in stylistic originality. Notably, the negative impact of low income is concentrated among composers from less privileged backgrounds, implying that financial support is crucial for fostering creativity and innovation. While we cannot make definitive causal claims, the consistency of our findings underscores the importance of financial stability for fostering innovation and risk-taking in creative fields.

Of course those results remind me of my own earlier book In Praise of Commercial Culture. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Classical music listening for the year

Overall it has been a very good listening year for me. I spent a good bit of time relearning the Shostakovich String Quartets in various recordings, most of all the Fitzwilliam String Quartet. I made more of a concerted attempt to learn the musics of Carl Nielsen and Kalevi Aho and Kurt Weill. Here are some particular recordings that got more than their share of listening time, most but not all of them new releases:

Johann Sebastian Bach, complete cantatas, Masaaki Suzuki.

Beethoven, Complete Trios for Piano, Violin, and Cello, Weiss Kaplan Stumpf Trio. Another example of “the best set of these pieces I ever have heard, and who the heck are these people?” And the same works by the van Baerle Trio.

Mishka Rushdie Momen, Reformation, keyboard works by Byrd, Gibbons, Bull, and Sweelinck.

Debussy Images, by Saskia Giorgini.

Galina Grigorjeva, Nature Morte, by Paul Hillier and the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir.

Georg Friedrich Handel, Eternal Heaven, music director Thomas Dunford.

Handel, 8 Great Suites for Harpischord, by Asako Ogawa.

Bruce Liu, Waves, music by Rameau, Ravel, and Alkan.

Charles-Camille Saint-Saëns, Symphonic Poems, Le Carnaval des Animaux, other works. That I actually like this music is one of the year’s bigger surprises for me.

Schubert piano trios and assorted works, by Tetzlaff, Tetzlaff, and the now departed Lars Vogt.

Stravinsky, The Soldier’s Tale, with Isabelle Faust and Dominique Horwitz.

Tchaikovsky, symphonies four and six, and orchestral music, conducted by Carlos Paita.

The best recordings of classical music — ever — are being created now. That is not what I would have expected, and it is a good counter to excessively negative cultural generalizations.

Addendum: Here is a Spotify playlist for many of those selections.

Germany chart of the day

Here is the link.

Thursday assorted links

1. The Grand Mosque in Abu Dhabi has a Cinnabon on its ground floor.

4. Can architecture reveal the spread of purdah?

5. Drones to map and follow buses?

6. How much should we trust developing country gdp?

7. David Wallace-Wells on the Covid contrarians (NYT). And from Zeynep (NYT).

8. “Large language models surpass human experts in predicting neuroscience results.”

9. The drone intrusions are probably Russia?

10. Hurdles to DOGE (NYT).

Thanksgiving and the Lessons of Political Economy

It’s been a while so time to re-up my 2004 post on thanksgiving and the lessons of political economy. Here it is with no indent:

It’s one of the ironies of American history that when the Pilgrims first arrived at Plymouth rock they promptly set about creating a communist society. Of course, they were soon starving to death.

Fortunately, “after much debate of things,” Governor William Bradford ended corn collectivism, decreeing that each family should keep the corn that it produced. In one of the most insightful statements of political economy ever penned, Bradford described the results of the new and old systems.

[Ending corn collectivism] had very good success, for it made all hands very industrious, so as much more corn was planted than otherwise would have been by any means the Governor or any other could use, and saved him a great deal of trouble, and gave far better content. The women now went willingly into the field, and took their little ones with them to set corn; which before would allege weakness and inability; whom to have compelled would have been thought great tyranny and oppression.

The experience that was had in this common course and condition, tried sundry years and that amongst godly and sober men, may well evince the vanity of that conceit of Plato’s and other ancients applauded by some of later times; that the taking away of property and bringing in community into a commonwealth would make them happy and flourishing; as if they were wiser than God. For this community (so far as it was) was found to breed much confusion and discontent and retard much employment that would have been to their benefit and comfort. For the young men, that were most able and fit for labour and service, did repine that they should spend their time and strength to work for other men’s wives and children without any recompense. The strong, or man of parts, had no more in division of victuals and clothes than he that was weak and not able to do a quarter the other could; this was thought injustice. The aged and graver men to be ranked and equalized in labours and victuals, clothes, etc., with the meaner and younger sort, thought it some indignity and disrespect unto them. And for men’s wives to be commanded to do service for other men, as dressing their meat, washing their clothes, etc., they deemed it a kind of slavery, neither could many husbands well brook it. Upon the point all being to have alike, and all to do alike, they thought themselves in the like condition, and one as good as another; and so, if it did not cut off those relations that God hath set amongst men, yet it did at least much diminish and take off the mutual respects that should be preserved amongst them. And would have been worse if they had been men of another condition. Let none object this is men’s corruption, and nothing to the course itself. I answer, seeing all men have this corruption in them, God in His wisdom saw another course fitter for them.

Among Bradford’s many insights it’s amazing that he saw so clearly how collectivism failed not only as an economic system but that even among godly men “it did at least much diminish and take off the mutual respects that should be preserved amongst them.” And it shocks me to my core when he writes that to make the collectivist system work would have required “great tyranny and oppression.” Can you imagine how much pain the twentieth century could have avoided if Bradford’s insights been more widely recognized?

*Blind Spots: When Medicine Gets It Wrong, and What It Means for Our Health*

That is the new book by Marty Makary. Since Makary has been nominated to head the FDA, I am surprised this work is not receiving more attention.

In the book, Makary is sympathetic to HRT, skeptical about a lot of antibiotic use (microbiome issues), says it is fine to ingest the cholesterol in eggs, and he is critical of earlier attempts to separate mothers and their babies. He believes silicone breast implants got a bum rap, and thinks we have screwed up the treatment of peanut allergies. A common theme is that there is too much groupthink in modern medicine and medical research. He wonders if we should be suspicious of fluoride, in part because of microbiome issues. He briefly worries about the ingestion of microplastics. I would not say I have concrete views on these questions, but overall I came away from this book comfortable with him running the FDA, at least relative to past candidates. I am skeptical of his views on fluoride, however, as the recent flurry of debate seems to have settled on a “fluoride is a net benefit” side. I also worry a bit he is picking on some easy cases (e.g., separating mothers from their babies), and not going hard enough on the incentive problems in U.S. health care and its research communities.

Makary is not obviously an accelerationist. Most of all, he likes to avoid groupthink and give matters a further look. While such a view is hard to disagree with, it makes me nervous in a bureaucratic context. In reality, “groupthink” is how many things get approved as quickly as they do. Just how many public health debates are we supposed to be reopening here? Should that be the priority of the FDA? Or should speeding up clinical trials and lowering their cost be the emphasis?

When he thinks about FDA matters, is he willing to have questions of incentives arise first in his thoughts? If so, that would be a break from his writing career so far.

I also would be curious to know why he thinks “his sides of these debates” will, on the whole, avoid groupthink more than the status quo has done. Lemon-picking from the status quo, even if we agree with him on every point, does not clarify this all-important question. Groupthink stems from incentives, and what kind of better incentives will he build into the U.S. health care system? He does write about “common sense,” and making things “physician-centered,” both fine and well, but I don’t see either of those as answering my questions in a scalable manner.

Makary wanted to approve and accelerate the Johnson and Johnson vaccine, a good sign in my view. Still, on some issues he will, for my tastes, be insufficiently consequentialist (“go ahead and let them try!”) and too worried about “getting the science right” and “sampling more data.”

Marty has strong academic and research credentials, here is his Wikipedia page. Here is more on what he has done, all positives in my view:

Makary is a director on the board at Harrow, an ophthalmic pharmaceuticals company, and an adviser to Sidecar Health, an insurance provider that aims to lower customer costs by eliminating provider networks and drug formularies.

He’s also chief medical adviser to Nava, a benefits brokerage, and chief medical officer at Sesame, a cash-pay health service market that offers compounded semaglutide, Stat reported over the weekend, raising questions about how Makary will approach the GLP-1 shortage brouhaha should he be confirmed.

Sesame’s founder, David Goldhill, wrote a well-known piece in The Atlantic about his father’s death from a hospital-acquired infection that references a surgery checklist Makary helped develop to reduce errors and adverse events.

During the pandemic he called for universal masking and opposed vaccine mandates. He supported national lockdowns and called for “first doses first.” He also raised doubts about children needing two doses of the Covid vaccine. Rather than relitigate whether those are all the correct views or not, I will simply note he is not a deregulator per se. He donated to Obama in 2008.

Here is a recent Russ Roberts podcast with Makary.

Overall, I see only upsides from this pick. Nonetheless I also see a good chance he focuses on reform directions where I think the expected benefits are small. So I am not excited by this pick, at least not yet.

Wednesday assorted links

Environmental “Justice” Recreates Redlining

It’s been said that the radical left often ends up duplicating the policies of the radical right, just under different names and justifications, e.g. separate but equal, scientific thinking is “white” thinking and so forth. Here’s another example from Salim Furth: the re-creation of redlining. Redlining was the practice of making it more difficult to access financial products such as mortgages by grading some neighborhoods as “hazardous” for investment. Either by design or result, redlining was often associated with minority populations.

Salim shows that Massachusetts has created a modern redlining system.

In Massachusetts, the context is that MEPA (its mini-NEPA) requires projects of a certain size to go through either a moderately-expensive or a quite-expensive process. Some types of projects automatically [require] the quite-expensive Environmental Impact Review process. The #maleg passed a 2021 “Environmental Justice” law, which defined certain people – oh euphemism treadmill! – as “Environmental Justice populations.”…So any housing (or other) project that requires a permit from a state agency and is within 1 mile of a “Environmental Justice population” now automatically triggers the expensive EIR process….How expensive? I was told it can run from $150k to $1m, and take 6 to 12 months. That’s a lot of additional delay in a state where delays are already extreme.

If there’s a, uh, silver lining here, it’s that “EJ Population” is defined so capaciously that it includes super-rich areas of Lexington (32% Asian, $206k median hh income), because all “minorities” are automatically disadvantaged. So it’s much less targeted to disinvested places than the original redlining. But the downside is that it’s *extremely well targeted* to discourage investment anywhere near transit or jobs. The non-EJ places are the sprawly exurbs. So maybe they *tried* to reinvent redlining, but all they really accomplished was reinventing subsidies for sprawl and raising housing costs along the way!

…This is a good, sobering reminder that for every 1 step forward by pro-housing advocacy, the blue states can manage 2 steps backward via wokery, proceduralism and anti-market ideas…

Jay Bhattacharya at the NIH

Trump has announced the appointment, so it is worth thinking through a few matters. While much of the chatter is about the Great Barrington Declaration, I would note that Bhattacharya has a history of focusing on the costs of obesity. So perhaps we can expect more research funding for better weight loss drugs, in addition to other relevant public health measures.

Bhattacharya also has researched the NIH itself (with Packalen), and here is one bit from that paper: “NIH’s propensity to fund projects that build on the most recent advances has declined over the last several decades. Thus, in this regard NIH funding has become more conservative despite initiatives to increase funding for innovative projects.”

I would expect it is a priority of his to switch more NIH funding into riskier bets, and that is all to the good. More broadly, his appointment can be seen as a slap in the face of the Fauci smug, satisfied, “do what I tell you” approach. That will delight many, myself included, but still the question remains of how to turn that into concrete advances in public health policy. Putting aside the possibility of another major pandemic coming around, that is not so easy to do.

My main worry is simply that NIH staff will not trust their new director. The problem is not so much GBD, which can be compartmentalized as a “political” stance, but rather the earlier claims that many more people had Covid early than we had thought, and that expected fatalities were going to be quite low, with a maximum of 40,000. We all make mistakes, the question is how those mistakes get processed. If you interrogate Perplexity it will report “Bhattacharya has not publicly acknowledged or confessed to these mistakes in his early predictions.” You don’t have to agree with Perplexity (though contrary cites are welcome!), rather it suffices to say that reflects a common perception of the scientific community. He also seemed to be pushing those low fatality estimates for longer than might have been considered appropriate. And that is indeed a problem for his tenure at the NIH.

The danger is simply that NIH staff will double down on risk aversion, and they may not so readily support any attempt to make the grants themselves riskier, or rooted in the greater discretion of program directors, a’la DARPA and the like. They will fear that their director will not sufficiently follow the evidence, or admit when mistakes are being made and reverse course. Even if you fully agree with GBD and the like, I hope you are able to see this as a relevant problem. Every institutional revolution requires supportive troops on the inside, even if they are only a minority.

I very much hope this works out well, but in the meantime that is my reservation.

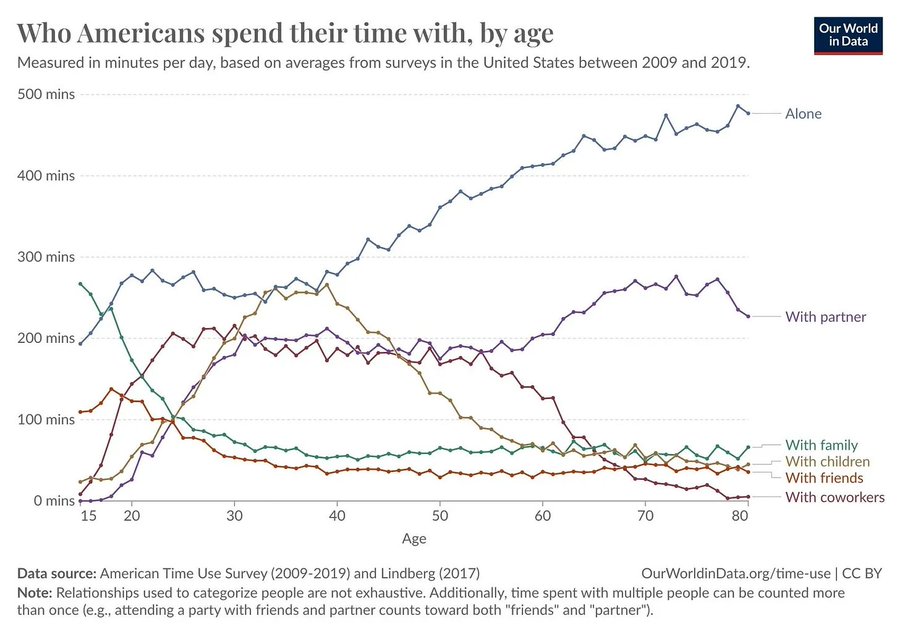

Who Americans spend their time with, by age

Via the excellent Bryan Caplan.

The Consequences of Limiting the Tax Deductibility of R&D

We study the tax payment and innovation consequences of limiting the tax deductibility of research and development (“R&D”) expenditures. Beginning in 2022, U.S. companies are required to capitalize and amortize R&D rather than immediately deduct these expenditures. We utilize variation in U.S. firms’ fiscal year ends to test the effects of the R&D tax change in a difference-indifferences framework. We first document that affected U.S. firms’ cash effective tax rates increase by 11.9 percentage points (62%), on average. We then test and find decreases in R&D investment among domestic-only, research-intensive, and constrained firms. In aggregate, these estimates translate to a reduction in R&D of $12.2 billion in the first year among the most research-intensive firms. Further, we observe decreased capital expenditures and share repurchases among affected companies, suggesting that firms also reduced other types of investment and shareholder payout to meet the increased cash tax liability. The paper provides policy-relevant evidence about the significant real effects of limiting innovation tax incentives.

That is from a new paper by Mary Cowx, Rebecca Lester, and Michelle L. Nessa. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Kevin Hassett to lead the NEC?

Bloomberg says so, a very good pick.

Can we expect large federal workforce cuts?

Wow, our government employees market is now projecting a new low of just 60k cuts For context, there are a record 23.4 million government employees When Elon Musk took over Twitter, he reduced the workforce by more than 80%

That is from Kalshi. Here is the market.

Tuesday assorted links

More Randian villains

Gavin Newsom, California’s Democratic governor, announced on Monday that he would reinstate a tax credit for electric vehicle purchases if the incoming Trump Administration removes federal EV tax credits. But the state may not extend the credits to Tesla because of the company’s large market share. Tesla’s stock price fell 4% on Monday.

Here is more from The Information (gated). GPT comments.