Results for “age of em” 16720 found

Teachers Don’t Like Creative Students

One of the most consistent findings in educational studies of creativity has been that teachers dislike personality traits associated with creativity. Research has indicated that teachers prefer traits that seem to run counter to creativity, such as conformity and unquestioning acceptance of authority (e.g., Bachtold, 1974; Cropley, 1992; Dettmer, 1981; Getzels & Jackson, 1962; Torrance, 1963). The reason for teachers’ preferences is quite clear creative people tend to have traits that some have referred to as obnoxious (Torrance, 1963). Torrance (1963) described creative people as not having the time to be courteous, as refusing to take no for an answer, and as being negativistic and critical of others. Other characteristics, although not deserving the label obnoxious, nonetheless may not be those most highly valued in the classroom.

….Research has suggested that traits associated with creativity may not only be neglected, but actively punished (Myers & Torrance, 1961; Stone, 1980). Stone (1980) found that second graders who scored highest on tests of creativity were also those identified by their peers as engaging in the most misbehavior (e.g., “getting in trouble the most”). Given that research and theory (e.g., Harrington, Block, & Block, 1987) suggest that a supportive environment is important to the fostering of creativity, it is quite possible that teachers are (perhaps unwittingly) extinguishing creative behaviors.

From Creativity: Asset or Burden in the Classroom?, a good review paper. What the paper shows is that the characteristics that teachers use to describe their favorite student correlate negatively with the characteristics associated with creativity. In addition, although teachers say that they like creative students, teachers also say creative students are “sincere, responsible, good-natured and reliable.” In other words, the teachers don’t know what creative students are actually like. (FYI, the research design would have been stronger if the researchers had actually tested the students for creativity.) As a result, schooling has a negative effect on creativity.

My experience as a parent is consistent with the idea that teachers don’t like creative students but I try not to blame the teachers too much. Creative people, for better and worse, ignore social conventions. Thus, it can be hard for teachers to deal with creative students in a classroom setting where they must guide 20-30 students en masse. As Jonah Lehrer puts it:

Would you really want a little Picasso in your class? How about a baby Gertrude Stein? Or a teenage Eminem? The point is that the classroom isn’t designed for impulsive expression – that’s called talking out of turn. Instead, it’s all about obeying group dynamics and exerting focused attention. Those are important life skills, of course, but decades of psychological research suggest that such skills have little to do with creativity.

One hope I have for personalized learning, ala the Khan Academy, is that teachers will not feel the need to suppress creative students when classroom dynamics do not require that all the students follow all the rules all the time .

Hat Tip: Erik Barker.

Are we stagnating aesthetically?

Some of you have been emailing, asking for my opinion of this recent Kurt Andersen Vanity Fair article. Here is the summary introductory paragraph:

For most of the last century, America’s cultural landscape—its fashion, art, music, design, entertainment—changed dramatically every 20 years or so. But these days, even as technological and scientific leaps have continued to revolutionize life, popular style has been stuck on repeat, consuming the past instead of creating the new.

There is plenty more at the link. A serious response would require a book or more, so let me offer a few conclusions, noting that it’s not possible in blog space to defend these judgments at any length. This is all about aesthetics, and it is distinct from the TGS technology argument, though one might believe that technical breakthroughs are needed to usher in aesthetic innovations, and that slowness in the one area would lead to slowness in the other. That’s not a claim I’ve ever made, but it’s worth considering even if it can’t be settled very easily. In any case, here’s my view of the evidence:

1. Movies: The Hollywood product has regressed, though one can cite advances in 3-D and CGI as innovations in the medium if not always the aesthetics. The foreign product is robust in quality, though European films are not nearly as innovative as during the 1960s and 70s. Still, I don’t see a slowdown in global cinema as a whole.

2. TV: We just finished a major upswing in quality for the best shows, though I fear it is over, as no-episode-stands-alone series no longer seem to be supported by the economics.

3. Books/fiction: It’s wrong to call graphic novels “new,” but they have seen lots of innovation. If we look at writing more broadly, the internet has led to plenty of innovation, including of course blogs. The traditional novel is doing well in terms of quality even if this is not a high innovation era comparable to say the 1920s (Mann, Kafka, Proust, others).

4. Computer and video games: This major area of innovation is usually completely overlooked by such discussions.

5. Music: Popular music has been in a Retromania sludge since the digital innovations of the early 90s, but classical contemporary music continues to show vitality and it is even establishing some foothold in the concert hall and in nightclubs too. Jazz has plenty of niche innovation, but it’s not moving forward with new, central ideas which command the attention of the field.

6. Painting and sculpture: Lots of good material, no breakthrough central movements comparable to Pop Art or Abstract Expressionism. Photography has seen lots of innovation.

7. Your personal stream: This is arguably the biggest innovation in recent times, and it is almost completely overlooked. It’s about how you use modern information technology to create your own running blend of sources, influences, distractions, and diversions, usually taken from a blend of the genres and fields mentioned above. It’s really fun and most of us find it extremely compelling. See chapter three of Create Your Own Economy/The Age of the Infovore.

8. Architecture: Slows down after 2008, but there were numerous innovative blockbuster buildings prior to the crash.

Today the areas of major breakthrough innovation are writing, computer games, television, photography (less restricted to the last decade exclusively) and the personal stream. Let’s hope TV can keep it up, and architecture counts partially. For one decade, namely the last decade, that’s quite a bit, though I can see how it might escape the attention of a more traditional survey. Some other areas, such as the novel, global cinema, and the visual arts are holding their own and producing plenty of small and mid-size innovations.

Although that is a relatively optimistic take on the aesthetics of the last decade, it nonetheless supports the view that aesthetic innovation relies on technological innovation. Most (not all) of the major areas of progress have relied on digitalization, and indeed that is the one field where the contemporary world has brought a lot of technological progress as well.

The New Da Vinci Code?

Over at Digitopoly Joshua Gans says that the breezy style of Launching the Innovation Renaissance (Nook, iTunes) makes it a page-turner “reminiscent of Dan Brown.”!!! I take this to mean that the book will sell millions of copies and be turned into a movie starring Tom Hanks; this does seem unlikely but after the Moneyball and Freakonomics movies who can say? FYI, Joshua is more confident than I am that the Coase theorem applies to rent division.

Over at Slate, Matt Yglesias also offers a short review saying the worst thing about the book is that it is too short!

Nick Schulz interviewed me at The American on some of the book’s themes, the WSJ also published part of this interview in their Notable and Quotable section.

Should speed limits be higher?

Arthur van Benthem, who is on the job market from Stanford, says no:

When choosing his speed, a driver faces a trade-off between private benefits (time savings) and private costs (fuel cost and own damage and injury). Driving faster also has external costs (pollution, adverse health impacts and injury to other drivers). This paper uses large-scale speed limit increases in the western United States in 1987 and 1996 to address three related questions. First, do the social benefits of raising speed limits exceed the social (private plus external) costs? Second, do the private benefits of driving faster as a result of higher speed limits exceed the private costs? Third, could completely eliminating speed limits improve efficiency? I find that a 10 mph speed limit increase on highways leads to a 3-4 mph increase in travel speed, 9-15% more accidents, 34-60% more fatal accidents, and elevated pollutant concentrations of 14-25% (carbon monoxide), 9-16% (nitrogen oxides), 1-11% (ozone) and 9% higher fetal death rates around the affected freeways. I use these estimates to calculate private and external benefits and costs, and find that the social costs of speed limit increases are three to ten times larger than the social benefits. In contrast, many individual drivers would enjoy a net private benefit from driving faster. Privately, a value of a statistical life (VSL) of $6.0 million or less justifies driving faster, but the social planner’s VSL would have to be below $0.9 million to justify higher speed limits. The substantial difference between private and social optimal speed choices provides a strong rationale for having speed limits. Although speed limits are blunt instruments that differ from an ideal Pigovian tax on speed, it is highly unlikely that any hidden administrative costs or unforeseen behavioral adjustments could make eliminating speed limits an efficiency-improving proposition.

College Subsidies Fuel Salaries

“Who pays a tax is determined not by the laws of Congress but by the law of supply and demand,” as Tyler and I say in Modern Principles. In particular, whether demanders or suppliers pay a tax is determined by the elasticities of demand and supply. The more elastic side of the market can better escape a tax, leaving more of it to be paid by the inelastic side. The same thing is true for a subsidy but in reverse, the inelastic side of the market gets the benefit of the subsidy. Virginia Postrel applies the idea to education and education subsidies.

If you offer people a subsidy to pursue some activity requiring an input that’s in more-or-less fixed supply, the price of that input goes up. Much of the value of the subsidy will go not to the intended recipients but to whoever owns the input. The classic example is farm subsidies, which increase the price of farmland.

A 1998 article in the American Economic Review explored another example: federal research and development subsidies. Like farmland, the supply of scientists and engineers is fairly fixed, at least in the short run. Unemployed journalists and mortgage brokers can’t suddenly turn into electrical engineers just because there’s money available, and even engineers and scientists are unlikely to switch specialties. So instead of spurring new activity, much of the money tends to go to increase the salaries of people already doing such work. From 1968 to 1994, a 10 percent increase in R&D spending led to about a 3 percent increase in incomes in the subsidized fields.

“A major component of government R&D spending is windfall gains to R&D workers,” the paper concluded. “Incomes rise significantly while hours rise little, and the increases are concentrated within the engineering and science professions in exactly the specialties heavily involved in federal research.”

The study’s author was Austan Goolsbee, then and now a professor at the University of Chicago but until recently the chairman of the president’s Council of Economic Advisers.

….Goolsbee declined a recent request to comment on the subject, but the parallels to higher education are hard to miss.

In the short-term, the number of slots at traditional colleges and universities is relatively fixed. A boost in student aid that increases demand is therefore likely to be reflected in prices rather than expanded enrollments. Over time, enrollments should rise, as they have in fact done. But many private schools in particular keep the size of their student bodies fairly stable to maintain their prestige or institutional character.

…On the whole, it seems that universities are like the companies making capital equipment. If the government hands their customers the equivalent of a discount coupon, the institutions can capture at least some of that amount by raising their prices

…This doesn’t mean that colleges capture all the aid in higher tuition charges, any more than capital-equipment companies get all the benefit of investment tax credits. But it does set up problems for two groups of students in particular. The first includes those who don’t qualify for aid and who therefore have to pay the full, aid-inflated list price. The second encompasses those who load up on loans to fill the gaps not covered by grants or tax credits only to discover that the financial value they expected from their education doesn’t materialize upon graduation.

Addendum: Long time readers may remember my rebuttal to Krugman on a similar point. Liberal Order has graphs and further discussion.

Assorted links

1. Private equity and jobs, setting the record straight.

3. Further notes on the new European agreement, if indeed that is what it is, and good comments here, and good tweet in Spanish.

4. The Economist picks best books of the year 2011, including TGS.

5. A professional NHL hockey player speaks to the issue of hockey helmets and collective action problems. Good, thoughtful piece, deeper than a lot of economic treatments of the same issue.

6. “our jet packs are here…”

Assorted links

Medical Patents Must Die

Prometheus gave man fire, thankfully he didn’t charge every time man lit a match. Prometheus Labs in contrast wants to charge patients for a rule that says when to increase or decrease a drug in response to a blood test. Quoting Tim Lee:

The patent does not cover the drug itself—that patent expired years ago—nor does it cover any specific machine or procedure for measuring the metabolite level. Rather, it covers the idea that particular levels of the chemical “indicate a need” to raise or lower the drug dosage.

Even this is not quite right for suppose a physician notes that the patient’s metabolites are within the range where a change in dosage is not necessary; although the physician takes no action she still has used the patent and thus must pay Prometheus Lab a fee or infringe.

We already have significant incentives for producing pharmaceuticals (and thus the instructions required to best use those pharmaceuticals), we support medical research through universities and non-profit hospitals, and there is plenty of opportunity to profit from the manufacture of tests. Will we really get enough additional innovation to justify the monopoly prices and deadweight losses when we enforce patents on medical rules? Remember, we have to pay the higher prices on all the rules not just the ones brought into being by the patent.

And if medical patents why not economic patents? Will Scott Sumner now patent a rule for adjusting the money supply in response to metabolites the futures market?

Patents like this are a logical consequence of the extension of patentable matter to software and business methods but extending patents to software and business methods has created huge legal costs without any increase in innovation.

Most importantly, patents can reduce innovation and are especially likely to do so in fields where innovations build on innovations. In fields of cumulative innovation, previous patents owners become veto players who can threaten to holdup the new innovation unless they are granted a share of the proceeds. In theory, bargaining can result in an efficient outcome. In practice, it means lawsuits, delay, waste and reduced innovation.

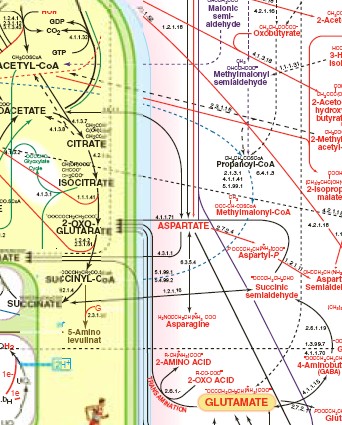

Since a smartphone may rely on many thousands of previous patents, the smartphone industry has heretofore been considered a classic case of how too many veto players can impede innovation. But now consider human metabolism, one of the most complicated systems known to man (just a tiny fraction of that system is shown at right), and note that if Prometheus is successful in this lawsuit that any correlation in that system can be patented. This is a recipe for disaster.

Addendum: Scotus Blog has a roundup of links. See Launching the Innovation Renaissance (Amazon link, B&N for Nook, also iTunes) for more on patents and their problems. Hat tip also to E.D. Kain who writes:

The world, it appears, is determined to turn me into a full-fledged libertarian. What with SOPA, PIPA, the NDAA, software patent trolling, police violence, and now patents on how doctors provide treatment to their patients, it’s becoming more and more clear how pernicious the law can be when it’s designed for powerful special interests, national security hawks, and big corporations.

Predictions about the eurozone

Charles Calomiris wrote in 1999 that the euro is doomed (pdf). Milton Friedman had some pretty good predictions about the euro. Here are my 2004 predictions about the euro, and here is my bit from 2003 (“The three percent rule is effectively dead…The real question is what will happen when one of the smaller nations thumbs its nose at France and Germany…and then claims exemption from the relevant penalties.”) I have been worried about euro-like arrangements since the late 1980s. Here are Paul Krugman’s 1998 remarks, though I am not sure which are his predictions and which are the scenarios he is distancing himself from; in any case he has been critical of the euro on numerous occasions. In the German language there is Theresia Theurl, among others, and add to that list some number of millions of Brits and Swedes.

How about the course of the eurocrisis? Here is my piece, “Last Man Standing” (jstor), published in The Wilson Quarterly in early 2009, written in 2008:

It has become increasingly clear that the problems in European governance are severe – and I am referring to the wealthier nations, not Bosnia and Albania. The European nations are tied to each other through the European Union and the euro, but they don’t have a good method for making collective decisions in contentious times.

…Spain, Italy, and Greece, which have all lost their premier AAA credit rating, may require some form of financial aid. The Germans might look to spread this burden around Europe, but there are few places to turn. France and the Netherlands could chip in, but the hat cannot be passed very widely.

Part of the problem for Europe is that its biggest banks are very large relative to the economies of their host nations – in other words, its component national economies are too small…It’s not widely recognized that Europe because of its systemic weaknesses, already has required implicit bailouts from the United States.

…Ideally, the ECB should take on a stronger role as lender of last resort in Europe, but the EU does not make such decisions easily. Fundamental alterations would be needed in the bank’s charter, which was written precisely to make change very difficult, in part because Germany…insisted on biasing the ECB toward conservatism and inaction. Even if the bank’s charter were amended, the member nations would surely impede any action by bickering over who would pay the bills for new initiatives. If the ECB is going to run bailouts, decision making will have to become a lot more fluid, and that would require Germany to give up control and the bank to move away from price stability as its sole objective. Since the EU member states have not been able to agree on a reform of the Union constitution, it’s not obvious they will be able to agree on changing the bank’s charter. They’ve had time – and good reason – to do so, yet have taken no serious action.

Roubini predicted the course of the current Italian financial crisis in 2006. And so on.

It is sometimes asserted that the economics profession should lose some status because so few economists predicted the U.S. financial crisis. I’m not sure economists should be judged by their ability to predict asset price movements, but grant the point. The euro crisis is now here, and it seems our profession should win some of its status back.

Organ Donors for Compensation

Today Alexander Berger will donate a kidney:

NYTimes: On Thursday, I will donate one of my kidneys to someone I’ve never met. Most people think this sounds like an over-the-top personal sacrifice. But the procedure is safe and relatively painless. I will spend three days in the hospital and return to work within a month. I am 21, but even for someone decades older, the risk of death during surgery is about 1 in 3,000. My remaining kidney will grow to take up the slack of the one that has been removed, so I’ll be able do everything I can do now. And I’ll have given someone, on average, 10 more years of life, years free of the painful and debilitating burden of dialysis.

Alexander doesn’t want any praise or talk of “heroic sacrifice,” that is part of the problem. He wants to normalize donation and he argues for compensation in a regulated market.

The people waiting for kidneys aren’t dying because of kidney failure; they’re dying because of our failure — without Congress’s misguided effort to ban organ sales, they would have been able to get the kidneys they desperately needed.

…There’s no reason that paying for a kidney should be seen as predatory. Last week, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals issued a ruling legalizing compensation for bone marrow donors; we already allow paid plasma, sperm and egg donation, as well as payment for surrogate mothers. Contrary to early fears that paid surrogacy would exploit young, poor minority women, most surrogate mothers are married, middle class and white; the evidence suggests that, far from trying to “cash in,” they take pride in performing a service that brings others great happiness. And we regularly pay people to take socially beneficial but physically dangerous jobs — soldiers, police officers and firefighters all earn a living serving society while risking their lives — without worrying that they are taken advantage of. Compensated kidney donors should be no different.

Here are further MR posts on organ donation and here is Jon Diesel on Do Economists Reach a Conclusion on Organ Donation.

Primate and pigeon nationalism

Even sillier than horse nationalism:

A monkey, which had crossed the Indian border, was arrested by wildlife officials in Bahawalpur, Express News reported on Monday.

As soon as the monkey entered the Cholistan area of Bahawalpur, locals tried to capture it but failed as the monkey dodged past them.

The residents of the area then informed the wildlife officials, who after some investigation and struggle, managed to capture the monkey.

The monkey was later placed at the Bahawalpur Zoo and has been named Bobby.

This is not the first case of such cross-border animal arrests.

Last year, Indian police held a pigeon under armed guard after it was caught on an alleged spying mission for Pakistan.

The link is here and for the pointer I thank Matt Gnagey.

Assorted links

1. How the sellers of wedding dresses limit arbitrage, and is the Target 2 debate all screwed up?

2. How to reemploy some ZMPers (an epistolary romance), and British royalty adopt ZMP Greek donkeys.

3. No one has a good theory of collateral.

4. Markets in everything, at two different levels, British royalty edition, via Bob Cottrell.

5. Blog with Perry Mehrling and others.

6. What the Khan Academy is really up to, namely measuring when learning occurs or not.

Nicholas Wapshott’s *Keynes Hayek*

I very much enjoyed this book — which is detailed and entertaining and conceptual all at once — and I wrote a lengthy review of it for National Review (not on-line that I can find, issue of 11/28). It’s a model of how to write popular history of economic thought, and still teach professional economists at the same time. Excerpt from my review:

For all his brilliance, Hayek didn’t — at the critical time — have a good enough understanding of the dangers of deflation. He didn’t realize the extent of sticky wages and prices and, more deeply, he didn’t see that ongoing deflation would render the “calculation problem” of a market economy more difficult…

Hayek’s biggest [recent] intellectual victory probably has come in the aftermath of the Obama fiscal stimulus. A lot of the modern-day Hayekians, most notably Mario Rizzo of New York University, predicted that the stimulus would not provide lasting aid to the economy but rather would impose an artificial boom-bust structure on the economy. The early spending of money would boost measured national income, but eventually those jobs would prove unsustainable: the stimulus funding would run out, the jobs would disappear, and the economy would slow down once again. That is exactly what we saw in the spring and summer of 2011.

A Hayekian perspective leads one rather naturally to the view — now quite vindicated — that the aid to state and local governments would preserve some jobs but the spending projects would mostly fail, including when it comes to sustainable job creation. It’s often neglected that Hayek’s macro is a general perspective which goes well beyond the particular cyclical story involving the time structure of production.

In the review, loyal MoneyIllusion readers will enjoy my discussion of Scott Sumner and how he fits into these debates (“These days I cannot go anywhere in the world of economics, or blog readers, without hearing his name.”).

You can buy the book here.

Addendum: I quite agree with Alex’s take on Hayek, and had drafted a post of my own, saying much the same thing. Eighty or so years later, people are still taking potshots at Prices and Production, among Hayek’s other works. Eighty years into the future, how many current Nobel Laureates will be receiving comparable attention?

Hayek and Modern Macroeconomics

David Warsh and Paul Krugman try to write Hayek out of the history of macroeconomics. Krugman writes:

Friedrich Hayek is not an important figure in the history of macroeconomics.

These days, you constantly see articles that make it seem as if there was a great debate in the 1930s between Keynes and Hayek, and that this debate has continued through the generations. As Warsh says, nothing like this happened. Hayek essentially made a fool of himself early in the Great Depression, and his ideas vanished from the professional discussion.

Warsh says much the same thing, adding, I am not making this up, a discussion of Hayek’s divorce. Neither Krugman nor Warsh attempt to argue for their positions, it’s all assertion. Both claim that Hayek is famous only because of the Road to Serfdom.

Let’s instead consider some of the reasons the Nobel committee awarded Hayek the Nobel:

Hayek’s contributions in the fields of economic theory are both deep-probing and original. His scholarly books and articles during the 1920s and 30s sparked off an extremely lively debate. It was in particular his theory of business cycles and his conception of the effects of monetary and credit policy which aroused attention. He attempted to penetrate more deeply into cyclical interrelations than was usual during that period by bringing considerations of capital and structural theory into the analysis. Perhaps in part because of this deepening of business-cycle analysis, Hayek was one of the few economists who were able to foresee the risk of a major economic crisis in the 1920s, his warnings in fact being uttered well before the great collapse occurred in the autumn of 1929.

It is true that many of Hayek’s specific ideas about business cycles vanished from the mainstream discussion under the Keynesian juggernaut but what Krugman and Warsh miss is that Hayek’s vision of how to think about macroeconomics came back with a vengeance in the 1970s.

David Laidler exaggerated but he was much closer to the truth than Krugman or Warsh when he wrote in 1982 regarding new-classical macroeconomics:

… I prefer the adjective neo-Austrian… In their methodological individualism, their stress on the market mechanism as a device for disseminating information, and their insistence that the business-cycle is the central problem for macroeconomics, Robert E. Lucas Jr., Robert J. Barro, Thomas J. Sargent, and Neil Wallace, who are the most prominent contributors to this body of doctrine, place themselves firmly in the intellectual tradition pioneered by Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich von Hayek.

Thus, Hayek was an important inspiration in the modern program to build macroeconomics on microfoundations. The major connecting figure here is Lucas who cites Hayek in some of his key pieces and who long considered himself a kind of Austrian. (Indeed, to the great consternation of some of my colleagues, I once argued that Lucas was the greatest Austrian economist of the 20th century.)

One can also judge Krugman’s claim that “the Hayek thing is almost entirely about politics rather than economics” by looking at who other Nobel laureates in economics cite. Is Hayek ignored because he is just a political thinker? Not at all, in fact in an interesting exercise David Skarbek finds that Hayek is cited by other Nobel laureates in their Nobel talks more than any other Nobel laureate with the exception of Arrow. (The top six cite-getters are Arrow, Hayek, Samuelson and then tied in citations for fourth place are Friedman, Lucas and Phelps.)

Addendum: Here is Pete Boettke and Russ Roberts and David Henderson.

India facts of the day

The $950bn worth of gold held by Indian households is the equivalent of 50 per cent of the country’s nominal GDP in dollar terms. All those gorgeous necklaces and other extravagances weigh 18,000 tonnes, or 11 per cent of the world’s stock, according to the report.

India imports 92 per cent of its gold, making it the third largest of its merchandise imports behind crude oil and capital goods. Gold made up 9.6 per cent of imports so far for the year ending March 2012 – significantly expanding the current account deficit.

That is an old criticism of the Indian economy, and here is some recent background on the deregulation of gold holdings.

On a different but related front, here is an overview of the ongoing deterioration of the Indian economy, still an underreported news story. Here are some economic lessons from Indian retail, a sector which is underperforming.