Results for “best book” 1946 found

*The Marginal Revolutionaries: How Austrian Economists Fought the War of Ideas*

That is the new and very interesting forthcoming book by Janek Wasserman, focusing on the history of the Austrian school of economics and due out in September. A few comments:

1. It is the best overall history of the Austrian school.

2. It is in some early places too wordy, though perhaps that is necessary for the uninitiated.

3. I don’t think actual “Austrian school members” will learn much economics from it, though it has plenty of useful historical detail, far more than any other comparable book. And much of it is interesting, not just: “Adolph Wagner and Albert Schaeffler taught in the Austrian capital in the 1860s and early 1870s, but quarrels with fellow incumbent Lorenz von Stein led to their departure.”

4. Even a full decade after its release in 1871, Menger’s Principles was not achieving much attention outside of Vienna.

5. The early Austrians favored progressive taxation and fairly standard Continental approaches to government spending.

6. The Austrian school of those earlier times was in danger of disappearing, as Boehm-Bawerk was working in government and the number of “Austrian students” was drying up, circa 1905.

7. The very first articles of Mises were empirical, and covered factory legislation, labor law, and welfare programs.

8. Wieser and some of the others lost status with the fall of the Dual Monarchy after WWI; Wieser for instance no longer had a House of Lords membership. Schumpeter and Mises responded to these changes by writing more for a broader public, often through newspapers (not blogs). Mises’s market-oriented views seemed to stem from this time.

9. Hayek in fact struggled in high school, though his grandfather had gone on Alpine hikes with Boehm-Bawerk.

10. The Lieder of the original Mises circle were patterned after the poems of Karl Kraus, and one of them mentioned spaghetti and risotto.

11. Much of this book is strong evidence for the “small group” theory of social change.

12. The patron institution for Hayek’s business cycle research of 1927 to 1931 was partly sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation.

13. By the mid-1930s, Mises, Tinbergen, Koopmans, and Nurkse were all living in Geneva. There was a Vienna drinking song saying farewell to Mises.

14. I wonder how these guys would have looked as Emergent Ventures applicants. [“We’re going to run away from the Nazis and recreate anew our whole school of thought in America, with thick Austrian accents…and with a night school class at NYU to boot.”]

15. The Austrian school eventually was reborn in the United States, which accounts for many more chapters in this book, some of them concerned with the ties between the Austrian school and libertarianism. There are some outright errors of fact in this section of the book, sometimes involving matters I was involved with personally (and which are non-controversial, not a question of “taking sides”). I think also the latter parts of the book do not quite grasp the extensive influence of the Austrian school on America, extending up through the current day, and covering such diverse areas as regulatory policy and tech and crypto.

Nonetheless, recommended as an important contribution to the history of economic thought.

Bloat Does Not Explain the Rising Cost of Education

In Why Are The Prices So D*mn High? Helland and I examine lower education, higher education and health care in-depth and we do a broader statistical analysis of 139 industries. Today, I will make a few points about education. First, costs in both lower and higher education are rising faster than inflation and have been doing so for a very long time. In 1950 the U.S. spent $2,311 per elementary and secondary public school student compared with $12,673 in 2013, over five times more (both figures in $2015). The rate of increase was fastest in the 1950s and 1960s–a point to which I will return later in this series.

College costs have also increased dramatically over time. For this book, we are interested in costs more than tuition because we want to know what society is giving up to produce education rather than who, in the first instance, is paying for it. Costs are considerably higher than tuition even today, although in recent years tuition has been catching up. Essentially students and their parents have been paying an increasing share of the increasing cost of higher education. Moreover, as with lower education, costs have been rising for a very long period of time.

I will take it as given that the explanation for higher costs isn’t higher quality. The evidence on tests scores is discussed in the book:

It is sometimes argued that how we teach has not changed but that what we teach has improved in quality. It is questionable whether studies of Shakespeare have improved, but there have been advances in biology, computer science, and physics that are taught today but were not in the past. However, these kinds of improvements cannot explain increases in cost. It is no more expensive to teach new theories than old. In a few fields, one might argue that lab equipment has improved, which it certainly has, but we know from figure 1 that goods in general have decreased in price. It is much cheaper today, for example, to equip a classroom with a computer than it was in the past.

The most popular explanation why the cost of education has increased is bloat. Elizabeth Warren and Chris Christie, for example, have both blamed climbing walls and lazy rivers for higher tuition costs. Paul Campos argues that the real reason college costs are growing is “the constant expansion of university administration.” Redundant administrators are also commonly blamed for rising public school costs.

The bloat theory is superficially plausible. The lazy rivers do exist! But the bloat theory requires longer and lazier rivers every year, which is less plausible. It’s also peculiar that the cost of education is rising in both lower and higher education and in public and private colleges despite very different competitive structures. Indeed, it’s suspicious that in higher education bloat is often blamed on competition–the “amenities arms race“–while in lower education bloat is often blamed on lack of competition! An all-purpose theory doesn’t explain much.

The bloat theory is superficially plausible. The lazy rivers do exist! But the bloat theory requires longer and lazier rivers every year, which is less plausible. It’s also peculiar that the cost of education is rising in both lower and higher education and in public and private colleges despite very different competitive structures. Indeed, it’s suspicious that in higher education bloat is often blamed on competition–the “amenities arms race“–while in lower education bloat is often blamed on lack of competition! An all-purpose theory doesn’t explain much.

More importantly, the data reject the bloat theory. Figure 8 shows spending shares in higher education. Contrary to the bloat theory, the administrative share of spending has not increased much in over thirty years. The research share, where you might expect to find higher lab costs, has fluctuated a little but also hasn’t risen much. The plant share which is where you might expect to find lazy rivers has even gone down a little, at least compared to the early 1980s.

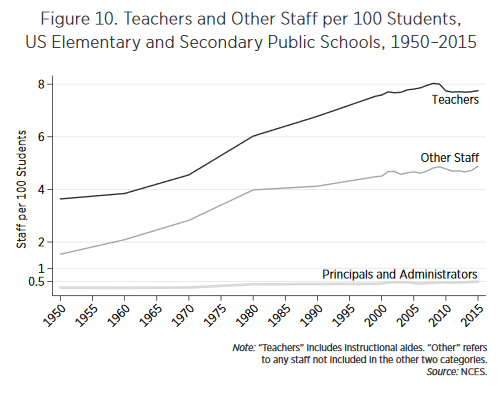

Nor is it true that administrators are taking over the public schools, see Figure 10.

Nor is it true that administrators are taking over the public schools, see Figure 10.

Compared with teachers and other staff, the number of principals and administrators is vanishingly small, only 0.4 per 100 students over the 1950–2015 period. It is true, if one looks closely, that the number of principals and administrators doubled between 1970 and 1980. It is unclear whether this is a real increase or a data artifact (we only have data for 1970 and 1980, not the years in between during this period). But because the base numbers are small, even a doubling cannot explain much. A bloated little toe cannot explain a 20-pound weight gain. Moreover, the increase in administrators was over by 1980, but expenditures kept growing.

If bloat doesn’t work, what is the explanation for higher costs in education? The explanation turns out to be simple: we are paying teachers (and faculty) more in real terms and we have hired more of them. It’s hard to get costs to fall when input prices and quantities are both rising and teachers are doing more or less the same job as in 1950.

We are not arguing, however, that teachers are overpaid!

Indeed, it is part of our theory that teachers are earning a normal wage for their level of skill and education. The evidence that teachers earn substantially above-market wages is slim. Teachers’ unions in public schools, for example, cannot explain decade-by-decade increases in teacher compensation. In fact, most estimates find that teachers’ unions raise the wage level by only approximately 5 percent. In other words, teachers’ unions can explain why teachers earn 5 percent more than similar workers in the private sector, but unions cannot explain why teachers’ wages increase over time.

If the case for unions as a cause of rising teacher compensation in public schools is weak, it is nonexistent for increased compensation for college faculty, for whom wage bargaining is done worker by worker with essentially no collective bargaining whatsoever.

A signal to where we are heading is this:

If increasing labor costs explain the increasing price of education but teachers are not overpaid relative to similar workers in other industries, then increasing labor costs must lead to higher prices in the education industry more than in other industries.

Read the whole thing. Next up, health care.

Addendum: Other posts in this series.

*Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World*

That is the new book by David Epstein, the author of the excellent The Sports Gene. I sometimes say that generalists are the most specialized people of them all, so specialized they can’t in fact do anything. Except make observations of that nature. Excerpt:

In an impressively insightful image, Tetlock described the very best forecasters as foxes with dragonfly eyes. Dragonfly eyes are composed of tens of thousands of lenses, each with a different perspective, which are then synthesized in the dragonfly’s brain.

I am not sure Epstein figures out what a generalist really is (and how does a generalist differ from a polymath, by the way?), but this book is the best place to start for thinking about the relevant issues.

Roissy has been deplatformed

Or so I hear, and Google doesn’t bring it up either, not even the shut down version.

I worry about deplatforming much less than many of you do. I remember the “good old days,” when even an anodyne blog such as Marginal Revolution, had it existed, had no platform whatsoever. All of a sudden millions of new niches were available, and many of us moved into those spaces.

In recent times, a number of the major tech companies have dumped some contributors, due to a mix of customer and employee protest. So we have gained say 99 instead of say 100, and of course I am personally happy to see many of the deplatformed sites go, or move to other carriers. Most of the deplatformed sites, of course, I am not familiar with at all, but that is endogenous. I would say don’t overreact to the endowment effect of having, for a while, felt one had literally everything. You never did. You still have way, way more than you did in the recent past.

You might be worried that, because of deplatforming, the remaining sites and writers and YouTube posters have to “walk the line” more than ideally would be the case. That to me is a genuine concern, but still let’s be comparative. Did you ever try to crack the New York publishing scene in the 1990s, or submit an Op-Ed to the New York Times before the internet was “a thing”? Now that was deplatforming, and most of it was due to the size of the slush pile rather than to evil intentions, though undoubtedly there was bias in both settings.

Another “deplatforming” came with the shift to mobile, which vastly favored some websites (e.g., Facebook) over many of the more idiosyncratic competitors, including many blogs (MR has done just fine, I should add).

Developments such as VR, AR, 5G — or whatever — will reshuffle the deck further yet. There will be big winners, many of which are not yet on the scene, and some considerable carnage on the downside. Maybe you won’t be forced off, but many of you will find it worthwhile to quit rather than adapt.

There still has never, ever been a better time to be a writer. What bugs people about deplatforming is the explicitness and potential unfairness of the decision. It’s like prom selection time, where there is no escaping the fact that the observed choices, at least once they get past the algorithms and are reviewed by the companies, reflect very conscious decisions to bestow and to take away. We have painful intuitions about such rank orderings…still, we are better served by the objective facts about today’s diversity and opportunity compared to that of the past.

I thank a loyal MR reader for the initial pointer.

John Lukacs has passed away at age 95

Here is a Washington Post obituary. Yes, he did write a bestselling tribute to Churchill, but more importantly he was one of the last representatives of a particular central European notion of history and culture. I much prefer the Times of Israel obituary. Here is Wikipedia. The Last European War and Budapest 1900: A Historical Portrait of a City and its Culture are two of my favorite books by him.

Big business isn’t big politics

That is my recent essay, adapted in Foreign Policy, from my new book Big Business: Love Letter to an American Anti-Hero. Here is the opening:

The basic view that big business is pulling the strings in Washington is one of the major myths of our time. Most American political decisions are not in fact shaped by big business, even though business does control numerous pieces of specialist legislation. Even in 2019, big business is hardly dominating the agenda. U.S. corporate leaders often promote ideas of fiscal responsibility, free trade, robust trade agreements, predictable government, multilateral foreign policy, higher immigration, and a certain degree of political correctness in government—all ideas that are ailing rather badly right now.

To be sure, there is plenty of crony capitalism in the United States today. For instance, the Export-Import Bank subsidizes U.S. exports with guaranteed loans or low-interest loans. The biggest American beneficiary is Boeing, by far, and the biggest foreign beneficiaries are large and sometimes state-owned companies, such as Pemex, the national fossil fuel company of the Mexican government. The Small Business Administration subsidizes small business start-ups, the procurement cycle for defense caters to corporate interests, and the sugar and dairy lobbies still pull in outrageous subsidies and price protection programs, mostly at the expense of ordinary American consumers, including low-income consumers.

…overall, lobbyists are not running the show. The average big company has only 3.4 lobbyists in Washington, and for medium-size companies that number is only 1.42. For major companies, the average is 13.9, and the vast majority of companies spend less than $250,000 a year on lobbying. Furthermore, a systematic study shows that business lobbying does not increase the chance of favorable legislation being passed for that business, nor do those businesses receive more government contracts; contributions to political action committees are ineffective too.

If you are looking for a villain, it is perhaps best to focus on how corporations sometimes help poorly staffed legislators evaluate and draft legislation. But again, national policy isn’t exactly geared to making businesses, and particularly big business, entirely happy.

References and further support are available in the book,

The Peter Principle Tested

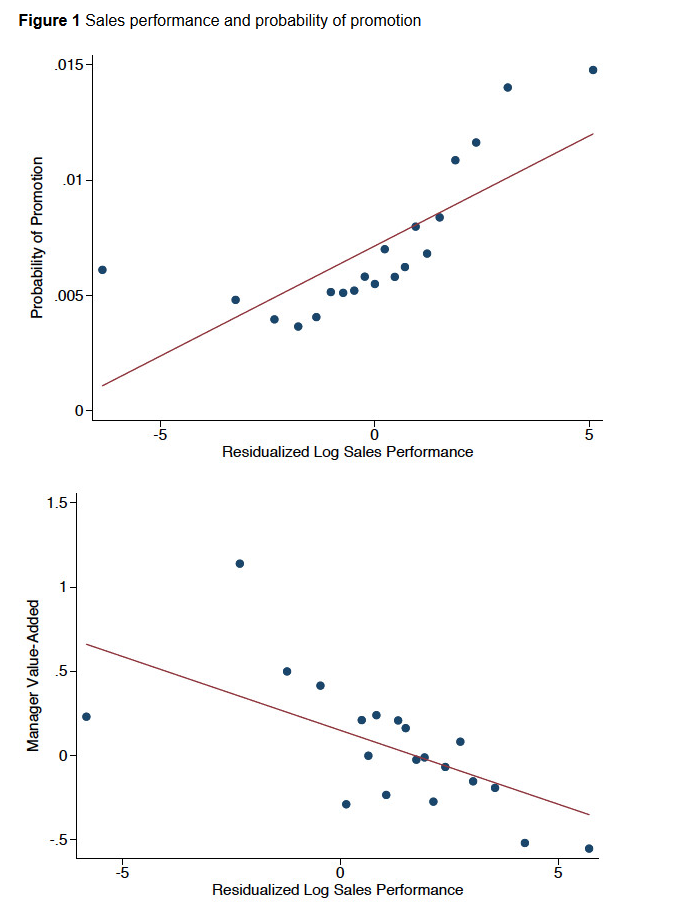

The Peter Principle is the observation that if people are good at doing their jobs they will be promoted. It follows that eventually everyone will be doing a job that they are not good at (otherwise they would have been promoted). The Peter Principle is tongue in cheek but it’s stuck around because it has an element of truth. Alan Benson, Danielle Li, Kelly Shue have put the principle to the test (summary here) by looking at promotions and performance of some 40,000 sales workers across 131 firms. Sales workers are a good place to look for the principle in action because it seems natural to promote the best sales people yet the best sales people do not necessarily make the best managers.

The Peter Principle is the observation that if people are good at doing their jobs they will be promoted. It follows that eventually everyone will be doing a job that they are not good at (otherwise they would have been promoted). The Peter Principle is tongue in cheek but it’s stuck around because it has an element of truth. Alan Benson, Danielle Li, Kelly Shue have put the principle to the test (summary here) by looking at promotions and performance of some 40,000 sales workers across 131 firms. Sales workers are a good place to look for the principle in action because it seems natural to promote the best sales people yet the best sales people do not necessarily make the best managers.

Figure One summarizes the main result: The best sales people as measured by sales revenue are more likely to be promoted (top) but their value added as managers actually declines in their (pre-promotion) sales revenues (bottom). The result isn’t difficult to believe, the best sales staff do not necessarily make the best managers, the best football players do not necessarily make the best coaches, the best professors do not necessarily make the best deans. But the result is deeper than this point because it raises questions about management. How can firms motivate top sales performers without promoting them to positions for which they may not be suitable? If sales revenue isn’t a good metric for manager potential, what is? The authors write:

We provide evidence that the Peter Principle may be the unfortunate consequence of firms doing their best to motivate their workforce. As has been pointed out by Baker et al. (1988) and by Milgrom and Roberts (1992), promotions often serve dual roles within an organisation: they are used to assign the best person to the managerial role, but also to motivate workers to excel in their current roles. If firms promoted workers on the basis of managerial potential rather than current performance, employees may have fewer incentives to work as hard.

We also find evidence that firms appear aware of the trade-off between incentives and matching and have adopted methods of reducing their costs. First, organisations can reward high performers through incentive pay, avoiding the need to use promotions to different roles as an incentive. Indeed, we find that firms that rely more on incentive pay (commissions, bonuses, etc.), also rely less on sales performance in making promotion decisions. Second, we find that organisations place less weight on sales performance when promoting sales workers to managerial positions that entail leading larger teams. That is, when managers have more responsibility, firms appear less willing to compromise on their quality.

Our research suggests that companies are largely aware of the Peter Principle. Because workers value promotion above and beyond a simple increase in salary, firms may not want to rid themselves entirely of promotion-based incentives. However, strategies that decouple a worker’s current job performance from his or her future career potential can minimise the costs of the Peter Principle. For example, technical organisations, like Microsoft and IBM have long used split career ladders, allowing their engineers to advance as individual contributors or managers. These practices recognise workers for succeeding in one area without transferring them to another.

Designing incentives is much more complicated than the carrot and the stick especially when workers contribute to firms in difficult to measure, multi-dimensional ways.

(fyi, our textbook, Modern Principles offers an introduction to incentive design).

*Open Borders: The Science and Ethics of Immigration*

That is the already-bestselling graphic novel by Bryan Caplan and Zach Weinersmith, and I would just like to say it is a phenomenal achievement. It is a landmark in economic education, how to present economic ideas, and the integration of economic analysis and graphic visuals. I picked it up not knowing what to expect, and was blown away by the execution.

To be clear, I don’t myself favor a policy of open borders, instead preferring lots more legal immigration done wisely. But that’s not really the central issue here, as I think Caplan and Weinersmith are revolutionizing how to present economic (and other?) ideas. Furthermore, they do respond in detail to my main objections to the open borders idea, namely the cultural problems with so many foreigners coming to the United States (even if I am not convinced, but that is for another blog post). Even if you disagree with open borders, this book is one of the very best explainers of the gains from trade idea ever produced, and it will teach virtually anyone a truly significant amount about the immigration issue, as well as economic analytics more generally.

There is more actual substance in this book than in many a purely written tome.

It will be out in October, you can pre-order it here.

Tax returns should not be made public information

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is an excerpt:

This idea has been suggested recently by Binyamin Appelbaum of The New York Times and also Matt Yglesias of Vox. In Norway it has been policy since 1814 and Finland does something similar.

I’m afraid, though, that universal tax transparency would boost U.S. economic inequality, take away second chances and devastate privacy.

And:

Or think about the dating market. Tax transparency would give high-earning men and women a bigger advantage and hurt their lower-earning competitors. Do we really wish to do that in an age of growing income inequality and diminished upward mobility?

Is it better if your parents and all your friends can see how well your new job is going or how much in royalties your last book earned? As it stands, we exist in a slightly more comfortable social equilibrium where your close associates assume the best or at least give you the benefit of the doubt. Transparency of earnings would increase stress and make failure and disappointment all too publicly evident. Or entrepreneurs with long-term projects which are going to make it — but not right away — might face too many social or family pressures to quit.

Snooping through the tax system would definitely happen. Evidence from Norway indicates that in 2007, 40 percent of Norwegian adults checked somebody’s tax information online, higher than the penetration of Facebook in Norway. Anonymity of the snooper was removed in 2014, and visits fell dramatically (88 percent by one measure), but still you can imagine paying others to snoop for you or the information eventually getting out over time.

The result of tax-record publication was that “this game of income comparisons negatively affected the well-being of poorer Norwegians while at the same time boosting the self-esteem of the rich,” according to Ricardo Perez-Truglia, a UCLA economics professor writing last week in VoxEU. There’s even a smartphone app that creates income leaderboards from the data on your Facebook friends.

Just as personal freedom and economic freedom are not so easily separable, the same is true for personal privacy and financial privacy. Are there actually people out there worried about Facebook privacy violations who wish to make all tax returns public and on-line?

Is work fun?

Ladders runs an excerpt from my book Big Business: A Love Letter to an American Anti-Hero, here is one part:

Another way to think about the non-pay-related benefits of having a job is to consider the well-known and indeed sky-high personal costs of unemployment. Not having a job when you want to be working damages happiness and health well beyond what the lost income alone would account for. For instance, the unemployed are more likely to have mental health problems, are more likely to commit suicide, and are significantly less happy. Sometimes there is a causality problem behind any inference—for instance, do people kill themselves because they are unemployed, or are they unemployed because possible suicidal tendencies make them less well suited to do well in a job interview? Still, as best we can tell, unemployment makes a lot of individual lives much, much worse. In the well-known study by economists Andrew E. Clark and Andrew J. Oswald, involuntary unemployment is worse for individual happiness than divorce or separation. Often it is more valuable to watch what people do rather than what they say or how they report their momentary moods.

There is much more at the link.

U.S.A. fact of the day, *Jump-Starting America*

The United States, as of 2014, spends 160 times as much exploring space as it does exploring the oceans.

That is from the new and interesting Jump-Starting America: How Breakthrough Science Can Revive Economic Growth and the American Dream, by Jonathan Gruber and Simon Johnson, two very eminent economists. And if you are wondering, I believe those numbers are referring to government efforts, not the private sector. I am myself much more optimistic about the economic prospects for the oceans than for outer space.

Most of all this book is a plea for radically expanded government research and development, and a return to “big science” projects.

Overall, books on this topic tend to be cliche-ridden paperweights, but I found enough substance in this one to keep me interested. I do, however, have two complaints. First, the book promotes a “side tune” of a naive regionalism: “here are all the areas that could be brought back by science subsidies.” Well, maybe, but it isn’t demonstrated that such areas could be brought back in general, as opposed to reshuffling funds and resources, and besides isn’t that a separate book topic anyway? Second, too often the book accepts the conventional wisdom about too many topics. Was the decline of science funding really just a matter of will? Is it not at least possible that federal funding of science fell because the return to science fell? Curing cancer seems to be really hard. Furthermore, some of the underlying problems are institutional: how do we undo the bureaucratization of society so that the social returns to science can rise higher again? Will a big government money-throwing program achieve that end? Maybe, but the answers on that one are far from obvious. This is too much a book of levers — money levers at that — rather than a book on complex systems. I would prefer a real discussion of how today science has somehow become culturally weird, compared say to Mr. Spock and The Professor on Gilligan’s Island. The grants keep on going to older and older people, and we are throwing more and more inputs at problems to get at best diminishing returns. Help!

Still, I read the whole thing through with great interest, and it covers some of the very most important topics.

U.S.A. fact of the day

According to publisher Penguin Random House, [Becoming] has sold more than 10 million copies — including hardcover, audiobooks and e-books — since its November release. That puts it near the top, if not the pinnacle, of all-time memoir sales.” It’s already the top-selling hardcover of last year, and it has outsold both of her husband’s books put together.

Here is the full story.

What I’ve been reading

1. Sarah A. Seo, Policing the Open Road: How Cars Transformed American Freedom. “The revolution in automotive freedom coincided with an equally unprecedented expansion in the police’s discretionary power.”

2. Allison Schrager, An Economist Walks into a Brothel, and Other Unexpected Places to Understand Risk. My blurb: “Allison Schrager’s An Economist Walks Into a Brothel is the best, most readable, most informative, most adventurous, and most entertaining take on risk you will find.”

3. Marlon James, Black Leopard Red Wolf. While the author of this new budding fictional series seems quite talented, this is more a book to admire than to enjoy. I can’t imagine that people will read it fifteen years from now. I’ve also read a bunch of reviews which try to praise it, without every telling the reader it will hold their interest.

4. Rachel M. McCleary and Robert J. Barro, The Wealth of Religions: The Political Economy of Believing and Belonging. A good overview of their work together on economics and religion, and also more generally a take on what the social sciences know empirically about the causes and effects of religion (not always so much, I should add).

5. The Bitter Script Reader, Michael F-ing Bay: The Unheralded Genius in Michael Bay’s Films. There aren’t enough enthusiastic, intelligent fanboy books, but this is one of them.

For prep for my Conversation with Knausgaard, I read a good deal of Ivo de Figueiredo, Henrik Ibsen: The Man & the Mask, and was impressed by how much new material he had uncovered.

Ben S. Bernanke, Timothy F. Geithner, and Henry M. Paulson, Firefighting: The Financial crisis and its Lessons: your model of this book is what this book is.

Arrived in my pile are:

Thomas Milan Konda, Conspiracies of Conspiracies: How Delusions Have Overrun America.

Uwe E. Reinhardt, Priced Out: The Economic and Ethical Costs of American Health Care. Uwe is gone but not forgotten.

Marion Turner, Chaucer: A European Life. This one may not please the Brexiteers.

Marie-Janine Galic, The Great Cauldron: A History of Southeastern Europe seems impressive, though I have not had time to read much of it.

Why is there so much suspicion of big business?

Perhaps in part because we cannot do without business, so many people hate or resent business, and they love to criticize it, mock it, and lower its status. Business just bugs them. After I explained the premise of this book to one of my colleagues, Bryan Caplan, he shrieked to me: “But, but . . . how can people be ungrateful toward corporations? Corporations give us everything! Corporations do everything for us!” Of course, he was joking, as he understood full well that people are often pretty critical of corporations. And they are critical precisely because corporations do so much for us. And do so much to us.

Does my colleague’s outburst remind you of anything? Well, immediately he followed up with this: “Hating corporations is like hating your parents.”

And:

There is another reason it doesn’t quite work to think of businesses as our friends. Friendship is based in part on an intrinsic loyalty that transcends the benefit received in any particular time and place. Many friendships also rely on an ongoing exchange of reciprocal benefits, yet without direct consideration each and every time of exactly how much reciprocity is needed. In addition to the self-interested joys of friendly togetherness, friendship is about commonality of vision, a wish to see your own values reflected in another, a sense of potential shared sacrifice, and a (partial) willingness to put the interest of the other person ahead of your own, without always doing a calculation about what you will get back.

A corporation just doesn’t fit this mold in the same way. A business may wish to appear to be an embodiment of friendly reciprocity, but it is more like an amoral embodiment of principles that usually but not always work out for the common good. The senior management of the corporation has a legally binding responsibility to maximize shareholder profits, at least subject to the constraints of the law and perhaps other constraints embodied in the company’s charter or by-laws. The exact nature of this fiduciary responsibility will vary, but it never says the company ought to be the consumer’s friend, at least not above and beyond when such friendship may prove instrumentally valuable to the ends of the company, including profit.

In this setting, companies will almost always disappoint us if we judge them by the standards of friendship, as the companies themselves are trying to trick us into doing. Companies can never quite meet the standards of friendship. They’re not even close acquaintances. At best they are a bit like wolves in sheep’s clothing, but these wolves bring your food rather than eat you.

Those are both excerpts from my final chapter “If business is so good, why is it so disliked?”, from my book Big Business: A Love Letter to an American Anti-Hero.

What do concert audiences really want?

Audiences only really like two parts of a show — the beginning and the end. You should prolong the former by rolling directly through your first three numbers without pausing. Then make sure you end suddenly and unexpectedly. Audiences rewards who stop early and punish those who stay late…

Finally, there’s nothing an audience enjoys more than hearing something familiar. If you think your songwriting and all-round musical excellence are enough to entertain a bunch of strangers for an hour with songs they have never heard before, bully for you. The Beatles didn’t, but what the hell do they know?

That is from the entertaining and insightful David Hepworth book Nothing is Real: The Beatles Were Underrated and Other Sweeping Statements About Pop. He lists the following as the ten best blues songs ever:

Memphis Jug Band: K.C. Moan

B.B. King: You Upset me Baby

Blind Willie Johnson: Dark Was the Night

Mississippi Fred McDowell: Shake ‘Em On Down

Lightnin’ Slim: Rooster Blues

Muddy Waters: Too Young to Know

Elmore James: I Can’t Hold Out

Otis Rush: All Your Love

Richard ‘Rabbit’ Brown: James Alley Blues

Blind Blake: Too Tight

By the way, Paul and the Beatles really did record both “I’m Down” and “Yesterday” in the same day.