Results for “pharmaceutical reciprocity” 21 found

UK to Adopt Pharmaceutical Reciprocity!

More than twenty years ago I wrote:

If the United States and, say, Great Britain had drug-approval reciprocity, then drugs approved in Britain would gain immediate approval in the United States, and drugs approved in the United States would gain immediate approval in Great Britain. Some countries such as Australia and New Zealand already take into account U.S. approvals when making their own approval decisions. The U.S. government should establish reciprocity with countries that have a proven record of approving safe drugs—including most west European countries, Canada, Japan, and Australia. Such an arrangement would reduce delay and eliminate duplication and wasted resources. By relieving itself of having to review drugs already approved in partner countries, the FDA could review and investigate NDAs more quickly and thoroughly.

Well, it’s happening! After Brexit, there were concerns that drugs would take longer to get approved in the UK because the EU was a much larger market. To address this, the UK introduced the “reliance procedure” which recognized the EU as a stringent regulator and guaranteed approval in the UK within 67 days for any drug approved in the EU. The Reliance Procedure essentially kept the UK in the pre-Brexit situation, and was supposed to be temporary. However, recognizing the logic of recognizing the EU, the UK is now saying that it will recognize other countries.

Our aim is to extend the countries whose assessments we will take account of, increasing routes to market in the UK. We will communicate who these additional regulators are and publish detailed guidance about this new framework in due course, including any transition arrangements for applications received under existing frameworks.

The UK is already participating in a mutual recognition agreement with the FDA over some cancer drugs. Therefore, it seems likely that the FDA will be among the regulatory authorities that the UK recognizes. If the UK does recognize the FDA, then we only need the FDA to recognize the UK for my scenario from more than 20 years ago to be fulfilled.

It’s thus time to revisit the Lee-Cruz bill of 2015, which proposed the Result Act (I was an influence).

Reciprocity Ensures Streamlined Use of Lifesaving Treatments Act (S. 2388), or the RESULT Act,” which would amend the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act to allow for reciprocal approval of drugs.

Addendum: Many previous posts on FDA reciprocity.

Pharmaceutical Reciprocity for Canada

If pharmaceutical reciprocity is a good idea for the United States, it’s a great idea for smaller countries. Indeed, this is mostly what happens in practice, even if not by law, since smaller countries can’t afford or justify the expensive US process. Fred Roeder of the Montreal Economic Institute makes the case for reciprocity in Canada:

…reciprocal recognition of drug approval authorities on both sides of the Atlantic would incentivize Canadian, European and American authorities to spend less time and money conducting parallel reviews. If the HPFB, the FDA or the EMA approved a drug, patients in Canada, Europe and America would have immediate access to it — increasing consumers’ choice as new drugs are offered to patients faster and more affordably, with less red tape driving up costs.

A reduction in approval time can be a win-win for patients and firms because a decrease in approval time is an increase in effective patent length without an actual increase in patent length. The numbers below are optimistic, but the idea that streamlining approval can increase profits and stimulate investment is correct:

These market-oriented reforms would not benefit not only consumers, but the pharmaceutical companies as well, expanding the timespan of the patents. On average, new drugs have a mere 10 to 14 years of patent protection remaining by the time they are sold to consumers after they have successfully jumped over all the government hurdles. Streamlining the drug approval process would increase the timespan of patented drugs on the market by 50 to 70 per cent.

Roeder also mentions Bart Madden’s important book Free to Choose Medicine. (For those who don’t know, I am proud to be the Bartley J. Madden chair in economics at Mercatus at GMU.)

Speeding Up Pharmaceutical Approvals by Recognizing Other Stringent Regulators

New Zealand’s ACT party has proposed that New Zealand speed up pharmaceutical approvals by recognizing the decisions of other stringent regulators, an idea I have long promoted .

The average time for Medsafe to consent an application for a high risk medicine is 630 days. For intermediate risk, it is 661 days and for lower risk it is 830 days8. The average time taken just for processing some lower risk categories is 176-210 days. This is an unacceptable length of time, given there other regulatory bodies replicating that exact same work overseas.

ACT says if a drug or medical device has been approved by any two reputable foreign regulatory bodies (such as Australia, United States, United Kingdom), it should be automatically approved in NZ as well within one week unless Medsafe can show extraordinary reason why it shouldn’t be.

This simple change would significantly improve access to medicines that have already been subject to rigorous testing and analysis through other regulatory regimes.

The ACT party is small but it has some seats and surprisingly the much larger National party is proposing a similar rule:

New Zealand’s slow approval process for medicines means Kiwis wait much longer than people in other countries to access potentially life-saving treatments. While it is essential that medicines and other treatments are subject to stringent scrutiny to ensure they are safe, there is no reason why New Zealanders should have to wait for our domestic medicines regulatory body, Medsafe, to conduct its own cumbersome process from scratch, when countries with health systems we trust have already gone through this exercise.

National will:…• Require Medsafe to implement even faster approvals processes for any medicines for use in New Zealand that have already been approved by at least two regulatory bodies that we currently recognise, including Australia, the EU, Singapore, the UK, Switzerland and the US.

New Zealand, by the way, already has a reciprocity agreement with the United States for food and it’s mutual–the FDA also recognizes New Zealand as a stringent food regulator–so the idea is not unprecedented.

Moreover, all of this comes on the tail of the UK actually adopting the idea via the “reliance procedure” which recognizes the EU as a stringent regulator and guarantees approval in the UK within 67 days for ay drug approved in the EU.

In the United States, even AOC has flirted with the idea, at least for sunscreens!

Thus, the reciprocity or recognition idea is starting to be adopted.

Hat tip: Eric Crampton who has some further comments.

Reciprocity and Muscular Dystrophy

For years, muscular dystrophy patients in the United States have been purchasing the drug deflazacort — used to stabilize muscle strength and keep patients mobile for a period of time — from companies in the United Kingdom at a manageable price of $1,600 a year.

But because an American company just got approval from the Food and Drug Administration to sell the drug in the United States, the price of the drug will soar to a staggering $89,000 annually, the Wall Street Journal reported last week.

Because the FDA restricts the importing of drugs from overseas if a version is available domestically, patients are stuck with the new, expensive version. This makes deflazacort the perfect case for advocates of international drug reciprocity — a reform that would make it easier for consumers to buy drugs that have been approved in other developed countries.

That is the introduction to an interview with yours truly in the Washington Post. I discuss thalidomide and the race to the bottom argument. Here is one other bit:

IT: Do you have any thoughts about the potential for FDA reform under this new administration and Congress?

AT: Peter Thiel’s speech at the Republican National Convention reminded us that we used to take big, bold risks — like going to the moon. Today, to say a project is a “moon shot” is almost a put-down, as if going to the moon never happened. We have become risk-averse and complacent, to borrow a term from my colleague Tyler Cowen. The result of the incessant focus on safety is playgrounds without teeter totters, armed guards at our schools and national monuments, infrastructure projects that no longer get built, and pharmaceutical breakthroughs that never happen.

The new administration is unpredictable, but when it comes to the FDA, unpredictable is better than business as usual.

The administration has yet to appoint a great FDA commissioner. Early names floated included Balaji Srinivasan, Jim O’Neill, Joseph Gulfo, and Scott Gottlieb but Srinivasan seems to have removed himself from the running. O’Neill would be great but I don’t think the US is ready, so that leaves Gulfo and Gottlieb. My suspicion is that Trump will like Gulfo because of Gulfo’s entrepreneurial experience but, as I said, the new administration is unpredictable.

Drug Reciprocity with Europe Gains Support

As loyal readers know, I’ve long been in favor of a system where a drug approved in another major, developed country is also approved here. For a long time it seemed as if I was shouting in the wilderness but in the last few years support for the idea has grown, as the Cruz-Lee Reciprocity bill indicates. In A Cure for Swelling Drug Prices: Competition, Greg Ip at the WSJ notes another new development:

Mr. Tabarrok says the FDA should also offer reciprocal approval of drugs that regulators in other advanced countries have already cleared. Imports of generics from countries with government-negotiated prices ought not to be as controversial as patent-protected drugs because they involve far less expensive and risky research. Indeed, the Generic Pharmaceutical Association and its European equivalent, Medicines for Europe, have proposed a “single development pathway” under which approval in one jurisdiction would automatically confer approval in the other.

The proposed plan is for generics only where the issues are simpler but Greg is right to conclude more generally:

The FDA has long insisted, for safety reasons, that it approve all drugs regardless of whether they have been approved overseas. But if the FDA was once a better regulator than its overseas peers, it isn’t now. Ken Kaitin, a professor of medicine at Tufts University who has studied drug regulation around the world, says there is “absolutely no evidence” the U.S. drug supply is safer than in Britain, Canada or Europe.

Thus, the FDA wouldn’t be compromising safety by harmonizing its approvals with foreign regulators. Indeed, by making more drugs available at lower cost, it could ultimately make Americans healthier.

Economists on FDA Reciprocity

Daniel Klein & William Davis surveyed economists about whether it would be an improvement to reform the FDA so that “as soon as a new drug is approved by any one of five [FDA approved international] agencies, that drug automatically gains approval in the United States.” They report:

Of the 467 economists who answered the question and did not mark “Have no opinion,” 53 percent agreed that the reform would be an improvement, while 29 percent disagreed. (The remainder said they were “neutral.”) Moreover, those favoring the reform were more likely to say they held their belief “strongly.” Hence, the balance of economist judgment certainly leaned in favor of the liberalization.

Economists are not the only ones in favor of reciprocity. Others are also coming around, at least partially. In Generic Drug Regulation and Pharmaceutical Price-Jacking I argued in response to the massive increases in the price of Daraprim (generic name Pyrimethamine) that we ought to allow importation:

Pyrimethamine is also widely available in Europe. I’ve long argued for reciprocity, if a drug is approved in Europe it ought to be approved here. In this case, the logic is absurdly strong. The drug is already approved here! All that we would be doing is allowing import of any generic approved as such in Europe to be sold in the United States.

In a paper in JAMA discussing the same case, Drs Jeremy Greene, Gerard Anderson, and Joshua M. Sharfstein agree, writing:

A second option is to temporarily permit the importation of drug products reviewed by competent regulatory authorities and approved for sale outside the United States. For example, Glaxo, the original manufacturer of pyrimethamine, sells a version of the drug approved for use in the United Kingdom at less than $1 per tablet.

Dr Sharfstein by the way was Principal Deputy Commissioner of the US Food and Drug Administration from March 2009 to January 2011.

Addendum: I will be discussing/debating pharmaceutical policy with Dr. Sharfstein at on event sponsored by the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington, DC the morning of Monday January 25. Invitation only but email me if you want an invite.

Generic Drug Regulation and Pharmaceutical Price-Jacking

The drug Daraprim was increased in price from $13.60 to $750 creating social outrage. I’ve been busy but a few points are worth mentioning. The drug is not under patent so this isn’t a case of IP protectionism. The story as I read it is that Martin Shkreli, the controversial CEO of Turing pharmaceuticals, noticed that there was only one producer of Daraprim in the United States and, knowing that it’s costly to obtain even an abbreviated FDA approval to sell a generic drug, saw that he could greatly increase the price.

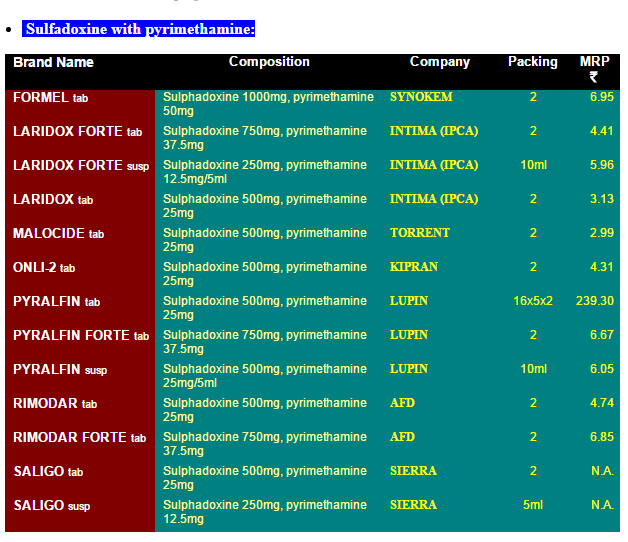

It’s easy to see that this issue is almost entirely about the difficulty of obtaining generic drug approval in the United States because there are many suppliers in India and prices are incredibly cheap. The prices in this list are in India rupees. 7 rupees is about 10 cents so the list is telling us that a single pill costs about 5 cents in India compared to $750 in the United States!

It is true that there are real issues with the quality of Indian generics. But Pyrimethamine is also widely available in Europe. I’ve long argued for reciprocity, if a drug is approved in Europe it ought to be approved here. In this case, the logic is absurdly strong. The drug is already approved here! All that we would be doing is allowing import of any generic approved as such in Europe to be sold in the United States.

Note that this is not a case of reimportation of a patented pharmaceutical for which there are real questions about the effect on innovation.

Allowing importation of any generic approved for sale in Europe would also solve the issue of so-called closed distribution.

There is no reason why the United States cannot have as vigorous a market in generic pharmaceuticals as does India.

Hat tip: Gordon Hanson.

Scott Sumner on Vaccine Nationalism

EconLib: Experts in the UK have looked at the AstraZenaca vaccine and found it to be safe and effective. And yet Americans are still not allowed to use the product. So if paternalism is not the actual motive, why do progressives insist that Americans must not be allowed to buy products not approved by the FDA? What is the actual motive?

The answer is nationalism. The experts who studied the AstraZenaca vaccine were not American experts, they were British experts. Can this form of prejudice be justified on scientific grounds? Obviously not. There has been no double blind, controlled study of comparative expert skill at evaluating vaccines. We have no way of knowing whether the UK decision is wiser than the FDA decision. Instead, the legal prohibition is being done on nationalistic grounds. We are told to blindly accept the incompetence of British experts, without any proof. (And even if you believed there was solid evidence that one country’s experts were better than another, it would not explain why each developed countries relies on their own experts. They can’t all be best!)

These debates always end up being like a game of whack-a-mole. Shoot down one argument and regulation proponents will simply put forth another. Their minds are made up. You say people shouldn’t be allowed to take a vaccine unless experts find it to be safe and effective? OK, the UK experts did just that. You say that only the opinion of US experts counts because our experts are clearly the best? Really, where is the scientific study that shows that our experts are the best? I thought you said we needed to “trust the scientists”? Now you are saying we must trust the nationalists?

…what’s wrong with the following three-part system of regulation as a compromise solution:

1. FDA approved drugs can be consumed by anyone in America.

2. Drugs approved by any of the top 20 advanced countries (but not the FDA) can be consumed by anyone willing to sign a consent form indicating that they understand the FDA has not approved this product. I’ll sign for AstraZeneca. (The US government puts together a list of 20 reputable countries.)

3. Drugs approved by none of the top 20 developed economies will still be banned.

This is what regulation would look like if paternalism actually were the motivating factor. But it’s not. It’s Trump-style nationalism that motivates progressives to insist that only FDA approved drugs can be sold in America. They may look down their noses at Trump, but they implicitly share his nationalism.

I agree, of course, and have long supported Pharmaceutical Reciprocity.

Burned by the FDA

If you lived in Great Britain or Germany and your physician prescribed a pharmaceutical, would you ask them, “has this pharmaceutical been approved by the U.S. FDA?” Probably not. At FDAReview.org Dan Klein and I argue that international reciprocity is a no-brainer:

If you lived in Great Britain or Germany and your physician prescribed a pharmaceutical, would you ask them, “has this pharmaceutical been approved by the U.S. FDA?” Probably not. At FDAReview.org Dan Klein and I argue that international reciprocity is a no-brainer:

If the United States and, say, Great Britain had drug-approval reciprocity, then drugs approved in Britain would gain immediate approval in the United States, and drugs approved in the United States would gain immediate approval in Great Britain. Some countries such as Australia and New Zealand already take into account U.S. approvals when making their own approval decisions. The U.S. government should establish reciprocity with countries that have a proven record of approving safe drugs—including most west European countries, Canada, Japan, and Australia. Such an arrangement would reduce delay and eliminate duplication and wasted resources. By relieving itself of having to review drugs already approved in partner countries, the FDA could review and investigate NDAs more quickly and thoroughly.

Unfortunately, even when they can, the US FDA does not take advantage of international knowledge as the WSJ notes in European Sunscreen Roadblock on U.S. Beaches:

Eight sunscreen ingredient applications have been pending before the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for years—some for up to a decade—for products available in many overseas countries. The applications were filed through the federal TEA process (time and extent application), which allows the FDA to approve the ingredients if they have been used for at least five years abroad and have proved effective and safe.

…Henry Lim, chairman of dermatology at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit and a member of the American Academy of Dermatology, says multiple UVA filters still awaiting clearance in the U.S. have been used effectively outside the country for years.

“The U.S. is an island by itself on this one,” he said. “They’re available in Canada, available in Europe, available in Asia, available in Mexico, and available in South America.”

The sunscreens available in the U.S. are not without risk and in some ways, as the WSJ discusses, the European standards are stricter than the US standards so there really is no reason why sunscreens available in Europe and Canada should not also be available in the United States.

Hat tip: Kurt Busboom.

Addendum: 27 states have driver’s license reciprocity with Germany. Why not pharmaceutical reciprocity? With hat tip to whatsthat in the comments.

Will Trump Appoint a Great FDA Commissioner?

A German newspaper asked for my take on the nomination of RFK Jr. to head HHS. Here’s what I said:

Operation Warp Speed stands as the crowning achievement of the first Trump administration, exemplifying the impact of a bold public-private partnership. OWS accelerated vaccine development, production, and distribution beyond what most experts thought possible, saving hundreds of thousands of American lives and demonstrating the power of American ingenuity in a time of crisis.

By nominating Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a prominent anti-vaccine activist, President Trump undermines his own legacy, and casts doubt on his administration’s commitment to protecting American lives through science-driven health policy.

Many better choices are available. Here is my 2017 post on potential people to head the FDA, many of which would also be great at HHS. No indent. Key points remain true.

As someone who has written about FDA reform for many years it’s gratifying that all of the people whose names have been floated for FDA Commissioner would be excellent, including Balaji Srinivasan, Jim O’Neill, Joseph Gulfo, and Scott Gottlieb. Each of these candidates understands two important facts about the FDA. First, that there is fundamental tradeoff–longer and larger clinical trials mean that the drugs that are approved are safer but at the price of increased drug lag and drug loss. Unsafe drugs create concrete deaths and palpable fear but drug lag and drug loss fill invisible graveyards. We need an FDA commissioner who sees the invisible graveyard.

Each of the leading candidates also understands that we are entering a new world of personalized medicine that will require changes in how the FDA approves medical devices and drugs. Today almost everyone carries in their pocket the processing power of a 1990s supercomputer. Smartphones equipped with sensors can monitor blood pressure, perform ECGs and even analyze DNA. Other devices being developed or available include contact lens that can track glucose levels and eye pressure, devices for monitoring and analyzing gait in real time and head bands that monitor and even adjust your brain waves.

The FDA has an inconsistent even schizophrenic attitude towards these new devices—some have been approved and yet at the same time the FDA has banned 23andMe and other direct-to-consumer genetic testing companies from offering some DNA tests because of “the risk that a test result may be used by a patient to self-manage”. To be sure, the FDA and other agencies have a role in ensuring that a device or test does what it says it does (the Theranos debacle shows the utility of that oversight). But the FDA should not be limiting the information that patients may discover about their own bodies or the advice that may be given based on that information. Interference of this kind violates the first amendment and the long-standing doctrine that the FDA does not control the practice of medicine.

Srinivisan is a computer scientist and electrical engineer who has also published in the New England Journal of Medicine, Nature Biotechnology, and Nature Reviews Genetics. He’s a co-founder of Counsyl, a genetic testing firm that now tests ~4% of all US births, so he understands the importance of the new world of personalized medicine.

The world of personalized medicine also impacts how new drugs and devices should be evaluated. The more we look at people and diseases the more we learn that both are radically heterogeneous. In the past, patients have been classified and drugs prescribed according to a handful of phenomenological characteristics such as age and gender and occasionally race or ethnic background. Today, however, genetic testing and on-the-fly examination of RNA transcripts, proteins, antibodies and metabolites can provide a more precise guide to the effect of pharmaceuticals in a particular person at a particular time.

Greater targeting is beneficial but as Peter Huber has emphasized it means that drug development becomes much less a question of does this drug work for the average patient and much more about, can we identify in this large group of people the subset who will benefit from the drug? If we stick to standard methods that means even larger and more expensive clinical trials and more drug lag and drug delay. Instead, personalized medicine suggests that we allow for more liberal approval decisions and improve our techniques for monitoring individual patients so that physicians can adjust prescribing in response to the body’s reaction. Give physicians a larger armory and let them decide which weapon is best for the task.

I also agree with Joseph Gulfo (writing with Briggeman and Roberts) that in an effort to be scientific the FDA has sometimes fallen victim to the fatal conceit. In particular, the ultimate goal of medical knowledge is increased life expectancy (and reducing morbidity) but that doesn’t mean that every drug should be evaluated on this basis. If a drug or device is safe and it shows activity against the disease as measured by symptoms, surrogate endpoints, biomarkers and so forth then it ought to be approved. It often happens, for example, that no single drug is a silver bullet but that combination therapies work well. But you don’t really discover combination therapies in FDA approved clinical trials–this requires the discovery process of medical practice. This is why Vincent DeVita, former director of the National Cancer Institute, writes in his excellent book, The Death of Cancer:

When you combine multidrug resistance and the Norton-Simon effect , the deck is stacked against any new drug. If the crude end point we look for is survival, it is not surprising that many new drugs seem ineffective. We need new ways to test new drugs in cancer patients, ways that allow testing at earlier stages of disease….

DeVita is correct. One of the reasons we see lots of trials for end-stage cancer, for example, is that you don’t have to wait long to count the dead. But no drug has ever been approved to prevent lung cancer (and only six have ever been approved to prevent any cancer) because the costs of running a clinical trial for long enough to count the dead are just too high to justify the expense. Preventing cancer would be better than trying to deal with it when it’s ravaging a body but we won’t get prevention trials without changing our standards of evaluation.

Jim O’Neill, managing director at Mithril Capital Management and a former HHS official, is an interesting candidate precisely because he also has an interest in regenerative medicine. With a greater understanding of how the body works we should be able to improve health and avoid disease rather than just treating disease but this will require new ways of thinking about drugs and evaluating them. A new and non-traditional head of the FDA could be just the thing to bring about the necessary change in mindset.

In addition, to these big ticket items there’s also a lot of simple changes that could be made at the FDA. Scott Alexander at Slate Star Codex has a superb post discussing reciprocity with Europe and Canada so we can get (at the very least) decent sunscreen and medicine for traveler’s diarrhea. Also, allowing any major pharmaceutical firm to produce any generic drug without going through a expensive approval process would be a relatively simply change that would shut down people like Martin Shkreli who exploit the regulatory morass for private gain.

The head of the FDA has tremendous power, literally the power of life and death. It’s exciting that we may get a new head of the FDA who understands both the peril and the promise of the position.

China’s Libertarian Medical City

You’ve likely heard of Prospera, the private city in Honduras established under the ZEDE (Zone for Employment and Economic Development) law, which has drawn global investment for medical innovation. The current Honduran government is trying to break its contracts and evict Prospera from  Honduras. The libertarian concept of an autonomous medical hub, free to attract top talent, pharmaceuticals, medical devices, ideas, and technology from around the world is, however, gaining traction elsewhere—most notably and perhaps surprisngly in the Boao Hope Lecheng Medical Tourism Pilot Zone in Hainan, China.

Honduras. The libertarian concept of an autonomous medical hub, free to attract top talent, pharmaceuticals, medical devices, ideas, and technology from around the world is, however, gaining traction elsewhere—most notably and perhaps surprisngly in the Boao Hope Lecheng Medical Tourism Pilot Zone in Hainan, China.

Boao Hope City is a special medical zone supported by the local and national governments. Treatments in Boao Hope City do not have to be approved by the Chinese medical authorities as Boao Hope City is following the peer approval model I have long argued for:

Daxue: Medical institutions within the zone can import and use pharmaceuticals and medical devices already available in other countries as clinically urgent items before obtaining approval in China. This allows domestic patients to access innovative treatments without the need to travel abroad…. The medical products to be used in the pilot zone must possess a CE mark, an FDA license, or PMDA approval, which respectively indicate that they have been approved in the European Union, the US, and Japan for their safe and effective use.

Moreover, evidence on the new drugs and devices used within the zone can be used to support approval from the Chinese FDA–this seems to work similar to Bartley Madden’s dual track procedure.

Daxue: Since 2020, the National Medical Products Administration has introduced regulations on real-world evidence (RWE), with the pilot zone being the exclusive RWE pilot in China. This means that clinical data from licensed items used within the zone can be transformed into RWE for registration and approval in China. Consequently, medical institutions in the zone possess added leverage in negotiations with international pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers seeking to enter the Chinese market.

… This process significantly reduces the time required for approval to just a few months, saving businesses three to five years compared to traditional registration methods. As of March 2024, 30 medical devices and drugs have been through this process, among which 13 have obtained approval for being sold in China.

The zone also uses peer-approval for imports of health food, has eliminated tariffs on imported drugs and devices and waived visa requirements for many medical tourists.

To be sure, it’s difficult to find information about Boao Hope medical zone beyond some news reports and press releases so take everything with a grain of salt. Nevertheless, the free city model is catching on. There are already 29 hospitals in the zone including international hospitals and hundreds of thousands of medical tourists a year. The medical zone is part of a larger free port project.

Prospera is ideally placed for a medical zone for North and South America. The Honduran government should look to China’s Boao Hope Medical Zone to see what Prospera could achieve for Honduras with support instead of oppositon.

Hat tip: MvH.

Peer Approval to Address Drug Shortages

Reuters: Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company said…that it is working with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to import and distribute penicillin in the country temporarily….Cuban’s Cost Plus will import Lentocilin brand penicillin powder marketed by Portugal-based Laboratórios Atral S.A.

There are two remarkable items in the above passage. First, there is a shortage of penicillin in the United States! Crazy. The second remarkable item is that the FDA has authorized the temporary importation of penicillin from Portugal. In other words, the FDA will accept the EMA’s authorization of penicillin as equivalent to its own, at least for the purposes of alleviating the shortage. That’s good. What is needed, however, is a more permanent form of peer-approval.

I have long advocated for peer approval or reciprocity for any drug or device approved in a peer country but notice that this form of peer approval is only for drugs already approved in the United States. Thus, the approval is really only for labeling and manufacturing, a pretty small ask.

Peer approval for imports would also help to discipline domestic firms who sometimes take advantage of monopoly power to jack up prices. Indeed, you may recall Martin Shkreli and the massive price increases for Daraprim (Pyrimethamine) to $750 a pill when the same pill was available in Europe for $1 or less and in India for 10 cents. Importation would have solved that problem entirely.

Deadly Precaution

MSNBC asked me to put together my thoughts on the FDA and sunscreen. I think the piece came out very well. Here are some key grafs:

…In the European Union, sunscreens are regulated as cosmetics, which means greater flexibility in approving active ingredients. In the U.S., sunscreens are regulated as drugs, which means getting new ingredients approved is an expensive and time-consuming process. Because they’re treated as cosmetics, European-made sunscreens can draw on a wider variety of ingredients that protect better and are also less oily, less chalky and last longer. Does the FDA’s lengthier and more demanding approval process mean U.S. sunscreens are safer than their European counterparts? Not at all. In fact, American sunscreens may be less safe.

Sunscreens protect by blocking ultraviolet rays from penetrating the skin. Ultraviolet B (UVB) rays, with their shorter wavelength, primarily affect the outer skin layer and are the main cause of sunburn. In contrast, ultraviolet A (UVA) rays have a longer wavelength, penetrate more deeply into the skin and contribute to wrinkling, aging and the development of melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer. In many ways, UVA rays are more dangerous than UVB rays because they are more insidious. UVB rays hit when the sun is bright, and because they burn they come with a natural warning. UVA rays, though, can pass through clouds and cause skin cancer without generating obvious skin damage.

The problem is that American sunscreens work better against UVB rays than against the more dangerous UVA rays. That is, they’re better at preventing sunburn than skin cancer. In fact, many U.S. sunscreens would fail European standards for UVA protection. Precisely because European sunscreens can draw on more ingredients, they can protect better against UVA rays. Thus, instead of being safer, U.S. sunscreens may be riskier.

Most op-eds on the sunscreen issue stop there but I like to put sunscreen delay into a larger context:

Dangerous precaution should be a familiar story. During the Covid pandemic, Europe approved rapid-antigen tests much more quickly than the U.S. did. As a result, the U.S. floundered for months while infected people unknowingly spread disease. By one careful estimate, over 100,000 lives could have been saved had rapid tests been available in the U.S. sooner.

I also discuss cough medicine in the op-ed and, of course, I propose a solution:

If a medical drug or device has been approved by another developed country, a country that the World Health Organization recognizes as a stringent regulatory authority, then it ought to be fast-tracked for approval in the U.S…Americans traveling in Europe do not hesitate to use European sunscreens, rapid tests or cough medicine, because they know the European Medicines Agency is a careful regulator, at least on par with the FDA. But if Americans in Europe don’t hesitate to use European-approved pharmaceuticals, then why are these same pharmaceuticals banned for Americans in America?

Peer approval is working in other regulatory fields. A German driver’s license, for example, is recognized as legitimate — i.e., there’s no need to take another driving test — in most U.S. states and vice versa. And the FDA does recognize some peers. When it comes to food regulation, for example, the FDA recognizes the Canadian Food Inspection Agency as a peer. Peer approval means that food imports from and exports to Canada can be sped through regulatory paperwork, bringing benefits to both Canadians and Americans.

In short, the FDA’s overly cautious approach on sunscreens is a lesson in how precaution can be dangerous. By adopting a peer-approval system, we can prevent deadly delays and provide Americans with better sunscreens, effective rapid tests and superior cold medicines. This approach, supported by both sides of the political aisle, can modernize our regulations and ensure that Americans have timely access to the best health products. It’s time to move forward and turn caution into action for the sake of public health and for less risky time in the sun.

A Pox on the FDA

Monkeypox isn’t in the same category of risk that COVID was before vaccines but it’s a significant risk, especially in some populations, and it’s a test of how much we have learned. The answer is not bloody much. Here’s James Walsh in NYMag:

As monkeypox cases have ticked up nationwide, the White House and federal agencies have repeatedly assured the public that millions of vaccine doses will be distributed to at-risk populations before the end of the year. Yet since the World Health Organization announced the global monkeypox outbreak in May, only tens of thousands of shots have been administered in the U.S. The slow start is due, at least in part, to the fact that 1.1 million doses have been stored in a Denmark pharmaceutical facility while the Food and Drug Administration has taken almost two months to approve their release here, according to people familiar with the situation. FDA officials only began to inspect the facility last week. The lag time, public-health experts say, is indicative of the federal government’s lackadaisical approach to a growing public-health emergency.

…It’s unclear why the FDA took so long to send inspectors to Denmark. The agency regularly conducted virtual inspections of drug facilities early in the COVID-19 pandemic, according to the agency’s guidance, and public-health activists are demanding answers. “Members of at risk communities are being turned away from monkeypox vaccination because these vaccines are not available in sufficient quantity in the U.S., but instead sitting in freezers in Denmark,” members of the advocacy group PrEP4All and Partners in Health wrote in a letter to federal officials overseeing the outbreak response last week.

Compounding their frustrations was the FDA’s refusal to accept an inspection done last year by its counterpart, the European Medicines Agency, which deemed the company’s facility in compliance with the FDA’s own standards.

“The FDA does not grant reciprocity for EMA authorization of any vaccines, for monkeypox or other diseases,” a spokesperson for the FDA said in a statement.

Is there anyone in the United States who is saying, “I am at risk of Monkeypox and I want the vaccine but I don’t trust the European Medicines Agency to run the inspection. I’d rather wait for the FDA!” I don’t think so. James Krellenstein, an activist on this issue, asks:

“Why were the Europeans able to inspect this plant a year ago, ensuring these doses can be used in Europe and the Biden Administration didn’t do the same,” he added. “The FDA is making a judgment that they’d rather let gay people remain unvaccinated for weeks and weeks and weeks than trust the European certification process.”

Many people want to be vaccinated:

New York City has received just 7,000 doses from the federal government amid the national vaccine shortage. Meanwhile, the city Department of Health and Mental Hygiene’s appointment booking system has failed to keep up with the high demand for the shots — most recently on Wednesday.

…The mounting frustrations left health officials and Mayor Eric Adams on the defensive, pushing back against comparisons to New York’s struggles during the early days of the coronavirus vaccine, which was beset by computer glitches and supply shortages.

This is a classic case for reciprocity. Any drug, vaccine, test or sunscreen (!) approved by a stringent regulatory authority ought to be conditionally approved in the United States.

Addendum: If you are not furious already–and you should be–remember that during COVID the FDA suspended factory inspections around the world creating shortages of life-saving cancer drugs and other pharmaceuticals. As I wrote then “Grocery store workers are working, meat packers are working, hell, bars and restaurants are open in many parts of the country but FDA inspectors aren’t inspecting. It boggles the mind.”

Hat tip: Josh Barro.

Photo Credit: Nigeria Centre for Disease Control.

Why Doesn’t the United States Have Test Abundance?!

We have vaccine abundance in the United States but not test abundance. Germany has test abundance. Tests are easily available at the supermarket or the corner store and they are cheap, five tests for 3.75 euro or less than a dollar each. Billiger! In Great Britain you can get a 14 pack for free. The Canadians are also distributing packs of tests to small businesses for free to test their employees.

In the United States, the FDA has approved less than a handful of true at-home tests and, partially as a result, they are expensive at $10 to $20 per test, i.e. more than ten times as expensive as in Germany. Germany has approved over 50 of these tests including tests from American firms not approved in the United States. The rapid tests are excellent for identifying infectiousness and they are an important weapon, alongside vaccines, for controlling viral spread and making gatherings safe but you can’t expect people to use them more than a handful of times at $10 per use.

We ought to have testing abundance in the US and not lag behind Germany, the UK and Canada. As usual, I say if it’s good enough for the Germans it’s good enough for me.

Addendum: The excellent Michael Mina continues to bang the drum.