Month: June 2012

Institutions and Islamic Law

Adeel Malik has a very interesting essay responding to Timur Kuran’s excellent book The Long Divergence. There are many previous MR posts on Kuran’s thesis that Islamic law impeded the transition to impersonal exchange in the Middle East (see here and here).

I think The Long Divergence is one of the most important recent contributions to New Institutional Economics (incidentally I reviewed it for Public Choice). Malik takes on board Kuran’s main argument but then argues that it is not institutional enough because it does not tackle the argument that Islamic law was endogenous to the politics of the region.

‘Islamic law can be described, at best, as a proximate rather than a deep determinant of development, and that there is limited evidence to establish it as a causal claim. Finally, I propose that, rather than exclusively concentrating on legal impediments to development, a more promising avenue for research is to focus on the co-evolution of economic and political exchange, and to probe why the relationship between rulers and merchants differed so markedly between the Ottoman Empire and Europe.’

Lack of trust is one reason why macro policy is underperforming

From my latest NYT column, here is one excerpt:

During the financial crisis, the prices of stocks, homes and other assets all fell, leaving the American public feeling less wealthy. In fact, the Federal Reserve reported last week that the crisis had erased almost two decades of accumulated prosperity for a typical family. The American economy and its financial system failed a giant stress test, at least when compared with previous expectations. Feeding the fears today are the crisis in the euro zone, the slowdown in China and political polarization at home.

In short, there is a prevailing sense that we are simply not as safe, financially speaking, as we used to be. The productive capacity of the economy may appear largely intact, but the perceived risk is significantly higher.

Think of hiring as a business investment, and that investment often requires:

1. A not too high risk premium

2. Consensus within organizations, and thus trust within organizations

3. Commitments from banks that they will provide liquidity when needed and not flinch in light of pressures to cut their balance sheets

4. Ability to afford concomitant capital costs

5. Ability to scale up rapidly if the new projects “hit paydirt”

6. Consumers perceive they have enough wealth to (potentially) become captive customers of a new and successful product

7. Affordable real wages

Inflating away the real wage helps with #7 — and that can be a big help indeed — but it is far from the entire picture. When trust is low, both monetary and fiscal policy will underperform, relative to textbook predictions.

Here is another bit:

In response, some people have moralized about this shift — sometimes by telling voters they’re stupid to let government shrink. But that kind of talk can lower public trust even further.

If your blogging or writing doesn’t increase the degree of trust among people who do not agree with each other, probably you are lowering the chance for better policy, not increasing it, no matter what you perceive yourself as saying. I also wrote:

Although Sweden and Switzerland have had effective monetary policies recently, both of those countries have especially high rates of trust in government.

And high trust in each other. I could have added Iceland to that list.

Taxes and the Onset of Economic Growth

In a recent book Besley and Persson 2011 argue that fiscal capacity is strongly correlated with economic performance across countries (see also here and here). They cite important historical work by Mark Dincecco who has shown that across Europe, between 1650 and 1900, higher taxes were associated with both limited government and economic growth (see here). The following graph is from Dincecco (2011) which contains similar figures for other European countries.

This finding can be interpreted in many ways. The state capacity literature emphasizes the idea that governments need an adequate tax system in order to provide the institutional preconditions necessary for economic growth.

Perhaps there is an alternative explanation for the historical correlation between higher taxes and economic growth. This has to do with selection bias in historical data sets. Modern states did not emerge out of nowhere. They replaced pre-existing local systems of taxation, patronage, and rent seeking. We have a relatively large amount of information about what strong, central, governments were doing and what taxes they were collecting. However, we do not have much information about local regulations or tax systems that existed before the rise of modern states because these local institutions were subsumed or destroyed by the state-building process. There is plenty of evidence that these local systems imposed large deadweight losses, although it is difficult to put together a database measuring how large these distortions were (see this paper by Raphael Frank, Noel Johnson, and John Nye or just read about the Gabelle; also see Nye (1997) for this point).

The implication of this argument is that an increase in the measured size of central government need not have been associated with an increase in the total burden of government. Rather the total deadweight loss of all regulations and taxes could have gone down in the 18th and 19th centuries, even as the tax rates imposed by the central state went up.

(Note: the increase in per capita revenues in England depicted in the figure is largely driven by higher rates of taxation (notably the excise) and more effective tax collection and not by Laffer curve effects (although the growth of a market economy during the 18th century did make it easier for the state to collect taxes).

Structural theories of unemployment, vindicated as part of the puzzle

From the new AER, by Michael Elsby and Matthew Shapiro:

That the employment rate appears to respond to changes in trend growth is an enduring macroeconomic puzzle. This paper shows that, in the presence of a return to experience, a slowdown in productivity growth raises reservation wages, thereby lowering aggregate employment. The paper develops new evidence that shows this mechanism is important for explaining the growth-employment puzzle. The combined effects of changes in aggregate wage growth and returns to experience account for all the increase from 1968 to 2006 in nonemployment among lowskilled men and for approximately half the increase in nonemployment among all men.

You will find many weak structural theories criticized (at length) in the blogosphere, but the stronger versions hold up. This is very likely one reason why the labor market and output response in recent years has been so weak. It doesn’t require any stories about companies searching desperately for quality computer programmers, and so showing the generality of unemployment across professions or regions isn’t much of a response to the stronger structural theories.

The Iron Law of Shoes

That is what Dan Klein and I used to call it. Now there is some research, by Omri Gillath, Angela J. Bahns, Fiona Ge, and Christian S. Crandall:

Surprisingly minimal appearance cues lead perceivers to accurately judge others’ personality, status, or politics. We investigated people’s precision in judging characteristics of an unknown person, based solely on the shoes he or she wears most often. Participants provided photographs of their shoes, and during a separate session completed self-report measures. Coders rated the shoes on various dimensions, and these ratings were found to correlate with the owners’ personal characteristics. A new group of participants accurately judged the age, gender, income, and attachment anxiety of shoe owners based solely on the pictures. Shoes can indeed be used to evaluate others, at least in some domains.

The piece is called “Shoes as a Source of First Impressions,” and for the pointer I thank @StreeterRyan. Via Mark Steckbeck, an ungated copy is here, for the price of your email address.

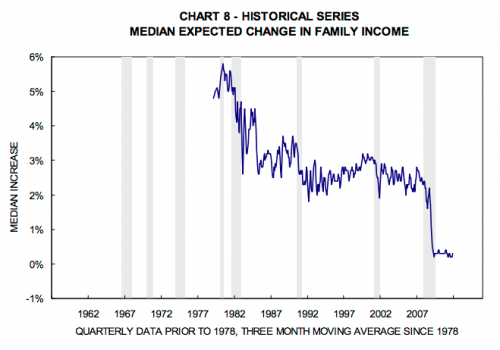

Median expected change in family income

Putting TGS issues aside, this is one reason why many of us do not see today’s macroeconomic problems as exclusively cyclical:

For the pointer I thank @rortybomb.

Some Interesting Recent Papers

- Why did the first states emerge? This paper argues that the traditional view that the ability to store an agricultural surplus allowed the rise of the state is incorrect for Malthusian reasons. Instead, they argue that the state first emerged when an increase in the transparency of agricultural production made it possible for a military elite to violently extract resources from farmers.

- Can game theory give us insights into online markets for stolen credit cards? Andrew Mell argues that trade between data thieves and data monetizers relies on a multilateral reputation-based enforcement mechanism. He goes on to suggest how policymakers could take actions that would cause this mechanism to unravel.

- Is veiling a rational strategy? This paper by Jean-Paul Carvalho develops an interesting theory that may shed light on the revival of veiling amongst certain Muslim communities in the past thirty years.

Markets in Everything: The Karl Marx Credit Card

The Karl Marx credit card now available in Eastern Germany for when you really need kapital. Planet Money is looking for taglines which you can tweet to @planetmoney. Here are a few good ones:

- Vanguard members get double reward points! #marxcard @planetmoney.

- “What’s in YOUR wallet? Seriously, though, I need to see your papers. Now.”

- @planetmoney There are some things money can’t buy. Especially if you abolish all private property. #marxcard.

Markets in everything

Conflict Kitchen is a take-out restaurant that only serves cuisine from countries with which the United States is in conflict. The food is served out of a take-out-style storefront that rotates identities every six months to highlight another country. Each iteration of the project is augmented by events, performances, and discussions that seek to expand the engagement the public has with the culture, politics, and issues at stake within the focus country. These events have included live international Skype dinner parties between citizens of Pittsburgh and young professionals in Tehran, Iran; documentary filmmakers in Kabul, Afghanistan; and community radio activists in Caracas, Venezuela.

That is in Pittsburgh, and Cuba and North Korea are on the way. Here is more, and for the pointer I thank Michael Rosenwald.

Is a high home ownership rate a sign of a successful country?

I saw an El Pais spread on this, which I cannot find on-line. Here are the European countries with the highest owner occupancy rates:

1. Romania, 97.5%

2. Lithuania, 93.1%

3. Croatia, 90.1%

4. Slovakia, 90.0%

How about the lowest rates?

1. Switzerland, 44.3%

2. Germany, 53.2%

3. Austria, 57.4%

Get the picture?

European City-States and Economic Growth

A long tradition claims that one factor that distinguished western Europe from China, the Middle East, and Russia was the presence of independent city-states. Max Weber, Henri Pirenne, and John Hicks argued that city-states played a crucial role in beginning the long road to modern economic growth (see this earlier MR post on producer and consumer cities).

De Long and Shleifer (1993) argued that city-states ruled by merchants favored policies that protected property rights and markets and that they imposed lower taxes than princely states did. But historians have found that cities like Florence actually imposed much higher taxes than feudal states did (see Epstein 1991, Epstein 1993 [JSTOR links], or Epstein 2000). Until now, however, no-one (to the best of my knowledge) has provided systematic evidence on the economic performance of independent city-states across Europe. A new paper by David Stasavage attempts to do just this. Using city population as a proxy for economic development, he finds that autonomous city-states overall didn’t grow faster than other cities. Interestingly, new city-states which had been independent for less than 200 years did grow faster. After more than 200 years of independence, growth in these independent cities slowed and they grew more slowly than did ordinary cities.

Stasavage interprets this finding in terms of a model of oligarchies proposed by Acemoglu (2008). Oligarchies initially have an incentive to impose institutions that favor markets and economic growth. However, oligarchies also impose barriers to entry, and over time these barriers to entry lead to growth slowing down. Other (complementary) mechanisms may also have been at work. In particular, Stasavage does not consider the role of external warfare. Once they became rich and prosperous, city-states were often attacked by neighboring territorial states. Many city-states then had to impose high taxes and other extractive policies in order to survive. In any case, these findings are significant for an argument that I will evaluate in subsequent posts that claims that the rise of state capacity played an important role in getting growth going in early modern Europe.

“Scene of the Verge of the Hay-Mead”

That is a chapter from Far From the Madding Crowd, which remains a much underrated Thomas Hardy novel. This chapter is a masterpiece of behavioral economics, most of all on matters of courtship and romance. It is difficult to excerpt, because it relies so much on the sequence of events and dialog. You can read it free here. There are other sources, including MP3s, here.

The Greek countercyclical asset

A clerk said books on economics and do-it-yourself guides were selling briskly, as were escapist thrillers and philosophy, especially works by Arthur Schopenhauer, known for his pessimism and his conviction that human experience is not rational or understandable.

There is more here, and I thank Asher Meir for the pointer.

Guest Blogger: Mark Koyama

We are pleased to have Mark Koyama blogging with us through Monday. Mark, our colleague at GMU, is an economic historian with an interest in institutional economics and the relationship between culture and economic performance. Mark’s paper on witches, taxes and the rule of law (with Noel Johnson) was recently covered at the Washington Post. Mark has also just published a paper in the Journal of Legal Studies on prosecution associations. Prosecution associations were private providers of insurance and police services in in early nineteenth-century England in the years before public police.

Mark’s career, however, has had one unusual feature. Mark began blogging as a student at Oxford but when he became a professor at GMU he defied all tradition and stopped blogging! We are thus happy to bring Mark back to the fold.

Has Africa always been the world’s poorest continent?

Jeff Sachs claims that Africa was always the poorest continent in the world, that many parts of Africa have never experienced economic growth, and that comparisons between African countries and Asian countries are highly misleading (see in this video for example).

Until recently it has been hard to establish basic stylized facts about African development because GDP data only goes back to 1960, but Ewout Frankema and Marlous van Waijenburg have been able to compile internationally comparable real wage estimates back to the 1880s (pdf). They follow Bob Allen’s influential methodology, constructing representative consumption bundles, and then seeing how many bundles an unskilled worker could obtain. The welfare ratios that result show that it simply makes no sense to talk about African economic performance in general in the colonial period.

There were at least two distinct economies in British colonial Africa, a comparatively high-wage, labor scarce, economy in West Africa, and a low-wage economy in East Africa. Real wages in many West African cities grew more or less continuously, from the 1880s until the 1930s, as these economies enjoyed a boom in commodity exports, and West African wages exceeded wages in many Asian cities through the colonial period. The story of poverty and stagnation in modern West Africa is not a story of permanent stagnation, but of growth collapses and growth reversals (especially in the 1970s and 1980s).

In contrast, real wages were extremely low in British East Africa. Many East African economies like Kenya never experienced rapid growth in the colonial period. It was the crisis of the 1970s that created the current view we have of all of sub-Saharan Africa as sharing a common set of problems. Modern Ghana, or the Gold Coast was roughly twice as rich as Kenya in the colonial period, but by the 1980s per capita GDP in the two countries was the same. Were the high real wages of the colonial period solely the rest of labor scarcity? (like the high wages recorded in medieval Europe after the Black Death) or did they represent a genuine moment of opportunity that could have led to sustained economic growth?

Consider this evidence in light of recent optimism about growth rates in Africa in the 2000s (see this MR post). Like the increase in real wages that occurred in the colonial period, recent growth has been driven by an export boom and rising commodity prices. These findings suggest that episodes of economic growth are less rare in African history than we might previously have supposed. Instead, perhaps the real difficulty lies in sustaining economic growth, and not in getting growth going for a few years.