Month: May 2014

Does rigid mobility imply low tax elasticities?

In an excellent review essay on Greg Clark, Arnold Kling says maybe so:

On the other hand, his findings argue against the need to create strong incentives to succeed. If some people are genetically oriented toward success, then they do not need lower tax rates to spur them on. Such people would be expected to succeed regardless. The ideal society implicit in Clark’s view is one in which the role of government is to ameliorate, rather than attempt to fix, the unequal distribution of incomes. As Clark puts it,

“If social position is largely a product of the blind inheritance of talent, combined with a dose of pure chance, why would we want to multiply the rewards to the lottery winners? Nordic societies seem to offer a good model of how to minimize the disparities in life outcomes stemming from inherited social position without major economic costs. (page 15)”

Assorted links

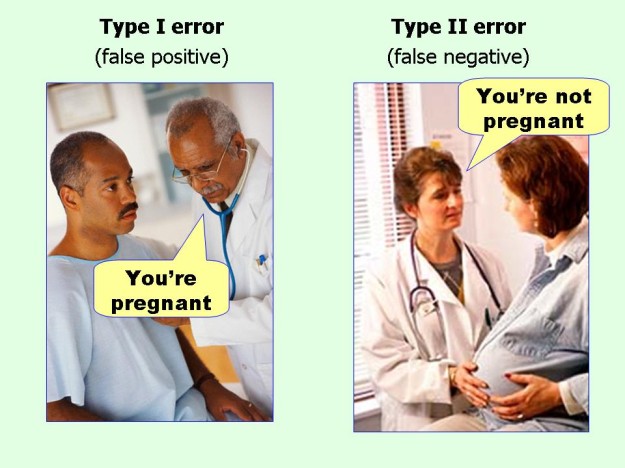

Type I and Type II Errors Simplified

Hat tip: Flowing data. Original?

*Think Like a Freak*

The authors are Levitt and Dubner and the subtitle is The Authors of Freakonomics Offer to Retrain Your Brain.

This is a beautifully written book, as good as the original Freakonomics.

My favorite parts were the discussion of the Japanese hot dog eater Kobayashi and his training/learning regime, why van Halen had the “no brown M&Ms” clause in its contract, and why Nigeriam spam scammers tell you they are from Nigeria.

You also can get the real story (or at least part of the real story) of how the authors helped the British authorities identify terrorist money laundering.

Addendum: Here is an excerpt from the book.

The affordability of competency-based learning?

How good a degree will this be?:

The $10,000 bachelor’s degree remains elusive. But Southern New Hampshire University’s College for America has unveiled self-paced, competency-based degrees that students should be able to complete for that price, or less.

The private university’s regional accreditor, the New England Association of Schools and Colleges, last week gave a green light to online bachelor’s degrees in health care management and communications from College for America, which is a nonprofit subsidiary of the university.

The college first began enrolling students last year. Until this week its sole option was an associate degree in general studies.

Tuition and fees at College for America are $1,250 per six-month term. The college uses a subscription-style model in which students can complete assessments at their own speed. The associate degree is designed for students to complete in an average of two years — at a cost of $5,000.

And:

…students can go from start to finish in four years, spending a total of $10,000…

Tuition subsidies will bring the price down further for many students. The college is heavily focused on employer partnerships, and has brokered arrangements with 50 companies and nonprofit employers, including McDonald’s, Sodexo and Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield. Employers steer potential students to the college. Most also cover some of the tuition.

The defined scholastic year has two twenty-six week terms, with no break. There is more here. By the way, here is a new proposal for accreditation on a class-by-class basis, so as to cover on-line education.

Make Work Bias

Here is our colleague Bryan Caplan with a great video on the Luddite fallacy or make work bias:

Assorted links

The commons are still tragic

Kevin Grier reports:

Paul Krugman points us to the success story of the rebound of US fish stocks. He then makes an amazing leap to climate change saying, “Fighting climate change isn’t really all that different from saving fisheries; if we ever get around to doing the obvious, it will be easier and more successful than anyone now expects.”

I actually agree with the first part, and the Vox article that Krugman links to makes the point pretty well, just not in the way Paul wants it to be made.

Now the big caveat: Yes, US fisheries seem to be recovering. But that’s not true for much of the rest of the world. And, given that the United States imports around 91 percent of its seafood, this is a pretty crucial caveat.

All told, the best-managed fisheries around the world — the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Norway, Iceland — only make up about 16 percent of the global catch, according to a recent paper in Marine Pollution Bulletin by Tony Pitcher and William Cheung of the University of British Columbia.

By contrast, more than 80 percent of the world’s fish are caught in the rest of the world, in places like Asia and Africa — where rules are often less strict. The data here is fairly patchy, but the paper notes that many of these nations are less likely to follow the UN’s Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries, and there’s evidence that “serious depletions” may be occurring…

In other words, overfishing, like climate change, is a global problem that the US can’t fix on its own. Our fish stocks are rebounding, and our carbon emissions are falling, but much of the rest of the world is moving in the wrong direction on both issues.

The full post is here.

California markets in everything

Frustrated San Francisco drivers who are fed up having to circle around trying find a parking space on the street can use a new app that allows them to purchase a spot from someone who is already parked in one.

The app, called ‘Monkey Parking,’ connects drivers looking for empty spaces with someone who is also on the app who is willing to give up their prized spot, but for a fee of anywhere between $5 and $20.

That article is here, and there is another here.

For pointers I thank John Thorne and Mark Thorson and Daniel Kent.

Meanwhile, here is markets in everything at Newport Beach High School, namely paying for higher “draft picks” for the prom…via George Pearkes.

Speaking of California, here is Virginia Postrel on overindividuation in Mother’s Day gift giving.

Stephen Williamson on the United States, and Canada

He wrote:

….one possible story about the U.S., post-2000, is that there was an important secular sectoral shift that commences around 2000, but was masked by the post-2000 housing boom, which was essentially construction under false pretenses. If the sectoral shift is what was driving what we see in the time series, it had to affect men more than women, the old not at all, prime age workers somewhat, and young workers a lot. This also must have been a sectoral shift that affected the U.S., but not Canada.

In my view the sectoral shift was of two primary kinds. First, there was a productivity slowdown, though it had weaker employment effects in the sectors with more women. (For instance, whether or not health care productivity went up a lot, for policy and demographic reasons the demand for nurses was robust. Here is evidence on how job shifts have favored women.) Second, Chinese competition and the general rise of emerging economies led to more incipient factor price equalization than we had been expecting, noting however that some of these forces showed up in quantities (i.e., jobs) rather than prices.

Here is evidence for the importance of the credit crunch in explaining the observed structure of losses.

These forces have been revealed only slowly, so the resulting “Great Reset” has unfolded slowly in turn. Often locked-in older workers have kept their previous situations, but employers have not sought to repeat those patterns by making new and comparable investments in younger workers. This is most apparent in academia but to a lesser extent this logic pervades many sectors of our economy. In Silicon Valley they are ruthless but auto manufacturers have moved to two-tiered wage structures, based largely on seniority. “Spot the two-tiered wage structure” would be an instructive and depressing parlor game to play. These two-tiered wage structures imply a lot of big future changes — scary for the most part — are already baked into the cake, but again they will unfold slowly.

Canada is different because growing resource wealth, much of it based in demand from China, underwrote their continuing growth. If anything, Canada is running the danger of becoming a super-unequal, brain-drained, Dutch-diseased resource-based economy. Albeit at a high standard of living and with generally good policy, albeit while piling up some longer term risks if resource prices were to go very soft.

The Williamson post covers many more topics, most of all labor markets. Like many of the best and underheralded posts in the blogosphere, it knows not to draw too firm a conclusion.

Nicholas Wade’s *A Troublesome Inheritance*

Overall I was disappointed by my read of this book and I write that as someone who very much has liked Wade’s NYT pieces on similar topics. I appreciated the honesty and courage of the work, but I felt Wade needed to have pushed deeper in book-length form.

For instance the discussion of intelligence and its evolution should have been drenched in the Flynn Effect. It wasn’t. The first few chapters didn’t cut to the chase quickly enough.

Wade makes a big mistake arguing that “race” is a coherent concept. Surely that is a semantic issue which cannot move his case forward much, but can hurt it if he fails to establish his claims.

There is much I admire about Greg Clark’s (previous) book, but Wade doesn’t seem to realize Clark has hardly any evidence in support of his “genetic origins of capitalism” thesis.

The word “Denisovan” didn’t appear nearly enough.

We are told that Ashkenazim Jews may have sacrificed visual and spatial skills for other forms of (superior?) intelligence, but what about all the great Soviet Jewish chess players and mathematicians? And did the shtetl really have so many more centuries of capitalistic training to offer than did say Istanbul? I’m not suggesting anyone is required to answer these questions, but once you start playing the generalization game — especially on this particular topic — one ought to spend a lot of time picking up or at least recognizing all these loose ends and indeed there are many of them.

Had Kindle not tracked the percentage so accurately, I would have been surprised when the book ended.

Ross Douthat offers some remarks and links to a few other reviews. VerBruggen had a good take on the book. Arnold Kling is reading it too. Here is Andrew Gelman’s review.

Overall reading this book didn’t budge my priors, which I suppose means…it did in fact budge my priors.

China fact of the day

Before the Communists came to power in 1949, China had only 22 dams of any significant size. Now the country has more than half of the world’s roughly 50,000 large dams, defined as having a height of at least 15 meters, or a storage capacity of more than three million cubic meters. Thus, China has completed, on average, at least one large dam per day since 1949. If dams of all sizes are counted, China’s total surpasses 85,000.

The source is here, via Udadisi.

Thursday assorted links

The Piketty Bubble?

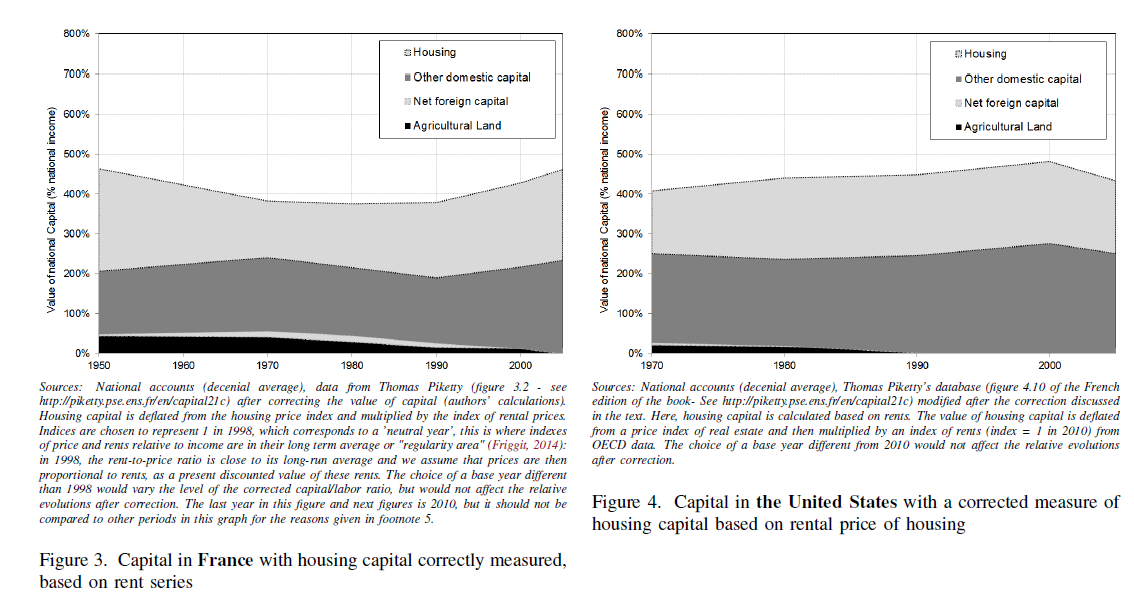

Piketty’s Capital is not very clear on how to distinguish greater physical capital from higher asset prices. For the most part, Piketty discusses capital as something that builds up over time through savings. The increase in physical capital then generates large returns to rentiers and those returns increases the capital share of income. When it comes to measuring capital, however, this has to be done in money terms which means that we need the price of capital. But the price of capital can vary significantly; as a result, Piketty’s capital stock can vary significantly even without changes in physical capital or savings. When capital increases because of changes in its price, however, the implications are quite different from a physical increase in capital.

Consider an asset that pays a dividend D forever; at interest rate r the asset is worth P=D/r. As r falls, the price of the asset rises. An asset that pays $100 forever is worth $1000 at an interest rate of 10% (.1) but $2000 at an interest rate of 5%. Piketty measures a higher P as more capital but notice that P is high only because r is low. You can’t, therefore, multiply P by some fixed r and conclude that rents have increased. Indeed, in this case rents, the dividend, haven’t increased at all. For the most part, Piketty simply ignores this issue (at least in the book) by arguing that changes in the price of capital wash out over long time periods but that does not appear to be the case in his data.

According to four French economists, Piketty’s measure of the capital stock is greatly influenced by the Europe-US housing bubble that preceded the financial crisis (Tyler earlier pointed to the French version of this paper, this is the English version). Since Piketty’s theory is based on rents from physical capital, the authors suggest that measures of housing capital based on prices should be corrected using the rent to price ratio. In other words, if the rentiers aren’t getting more rents then their capital hasn’t really increased. When measured in this way, the authors find little to no increase in the capital stock in either France or the United States.

Addendum: Do note that the debate here is not about income inequality but rather the source of income inequality and the implications for the future that Piketty draws from a (possibly not) rising capital stock.

Will brands end up marketing to your algorithms?

It suggests a world where an automated guardian manages our lives, taking away the awkward detail; the boring tasks of daily existence, leaving us with the bits we enjoy, or where we make a contribution. In this world our virtual assistants would quite naturally act as barriers between us and some brands and services.

Great swathes of brand relationships could become automated. Your energy bills and contracts, water, gas, car insurance, home insurance, bank, pension, life assurance, supermarket, home maintenance, transport solutions, IT and entertainment packages; all of these relationships could be managed by your beautiful personal OS.

Brands in these categories could find themselves dealing with the digital butler (unless we, the consumer, step in and press the override button), in which case marketing in these sectors could become programmatic in the truest sense.

It’s entirely possible that the influence of our virtual minders could reach far further. What if we tell our OS that we’ll only ever buy products that meet certain ethical standards; hit certain carbon emission targets or treat their employees in a certain way? Our computer may say no to brands for many different reasons.

There is more on that idea here.