Month: January 2016

A question about deep reading

Brad asks:

Prof. Cowen – I’m a longtime MR reader, but just came across an old post on your prolific reading. In the post, you mention:

“But it is not like the old days when I would set aside two months to work through The Inferno, Aeneid, and the like, with multiple secondary sources and multiple translations at hand. I no longer have the time or the mood, and I miss this.”

I am intrigued by this process of deep reading the canonical classics – have you detailed your method/routine for this anytime on MR?

Thanks!

Here is my preferred method:

1. Read a classic work straight through, noting key problems and ambiguities, but not letting them hold you back. Plow through as needed, and make finishing a priority.

1b. Mark up the book with bars and questions marks, but don’t bother writing out your still-crummy thoughts. That will slow you down.

2. After finishing the classic, read a good deal of the secondary literature, keeping in mind that you now are looking for answers to some particular questions. That will structure and improve your investigation. But do not read the secondary literature first. You won’t know what questions will be guiding you, plus it may spoil or bias your impressions of the classic, which is likely richer and deeper than the commentaries on it.

3. Go back and reread said classic, taking as much time as you may need. If you don’t finish this part of the program, at least you have read the book once and grappled with some of its problems, and taken in some of its commentators. If you can get through the reread, you’ll then have achieved something.

4. I am an advocate of the “close in time” reread, not the “several years later” reread. The several years later reread works best when it has been preceded by a close in time reread, otherwise you tend to forget lots, or never to have learned it to begin with, and the later reread may be more akin to starting a new book altogether.

5. If you want to find new things in books you already know and love, opt for new editions, new translations, and new typesettings where you will encounter it as a very different visual and conceptual field.

Testing free market environmentalism for rhino horns

South Africa’s high court has upheld a decision to legalize domestic sales of rhinoceros horn, a controversial plan that some hope will reduce poaching by creating a legal source of supply, but limited to South Africa, for the endangered animal’s parts.

…John Hume, a rancher in South Africa with more than 1,100 rhinos, made the application with another farmer to overturn the ban. He said he can only afford to keep his farm going if the local horn trade is legalized.

Here is the WSJ story, and here is another useful source. Note this:

Right now, there are only 29,000 rhinos left on the planet, most of which are in South Africa. It’s an incredible drop from the 500,000 that roamed Earth at the start of the 1900s, and sadly, the majority have been killed as a result of poaching, which increased 9,000 percent (yes, you read that right) between 2007 and 2014.

That means more than 1,000 rhinos are now killed illegally each year for their horns. Most of these end up in Asia, where they can reach up to US$100,000 per kilogram on the black market. Those prices are driven by the fact that many countries see rhino horn as a status symbol, and in Vietnam it’s believed (with no evidence whatsoever) to cure cancer.

Farmers claim they can harvest rhino horn without killing the animals, critics claim that rhinos will be in danger as long as the Asian demand continues, and in essence legalization cannot make supply sufficiently elastic, sufficiently quickly, to solve the problem.

Friday assorted links

1. NYT Adam Shatz profile of Kamasi Washington.

2. Ryan Avent on how ideological are economists?

3. Excellent TNR review on Tim Leonard’s excellent new book on eugenics and the history of progressive economic thought.

4. The demands made at Oberlin; the president says no to them by the way.

5. “We conclude that the overall economic consequences of the Chavez administration were bleak.”

6. One (American) couple lived off food waste for six months.

When will self-driving cars be a real thing?

We discussed this at lunch yesterday, here are my predictions:

1. Singapore will have driverless or near driverless neighborhoods in less than five years. But it will look more like mass transit than many aficionados are expecting.

2. The American courts and regulators will not pin too much liability on the car companies or software architects. That said, the regulators will move slowly, and for some time will require a human driver stay at the wheel, even though this seems to be more dangerous.

3. Mapping the territory, reliably, will remain the key problem. Until that is solved, driverless cars will be a form of mass transit — except without the mass — along predesignated routes.

4. A Chinese city will do it before America does, but Singapore first of all.

5. In less than two or three years, you will see some American car dealership advertising “driverless cars,” but in a gimmicky way. You’ll still have to sit at the wheel and…drive them. But they’ll park themselves and have super-duper cruise control and the like.

6. The big gains come from everyone having driverless cars and that is more than twenty years away, but well under fifty years away.

Here is a related NYT article. I thank Megan McArdle, Robin Hanson, Alex, and others for their contributions to this conversation.

Addendum: We also talked about whether “Virtual Reality” will be a revolutionary technology. It will have its fans, but I don’t see it as a major breakthrough. It makes too many people dizzy, and doesn’t really have a killer app; perhaps it will change sex however.

How ideological are economists?

From Ryan Avent:

Anthony Randazzo of the Reason Foundation, a libertarian think-tank, and Jonathan Haidt of New York University recently asked a group of academic economists both moral questions (is it fairer to divide resources equally, or according to effort?) and questions about economics. They found a high correlation between the economists’ views on ethics and on economics. The correlation was not limited to matters of debate—how much governments should intervene to reduce inequality, say—but also encompassed more empirical questions, such as how fiscal austerity affects economies on the ropes. Another study found that, in supposedly empirical research, right-leaning economists discerned more economically damaging effects from increases in taxes than left-leaning ones.

There is considerably more at the link. The Randazzo and Haidt study is from Econ Journal Watch.

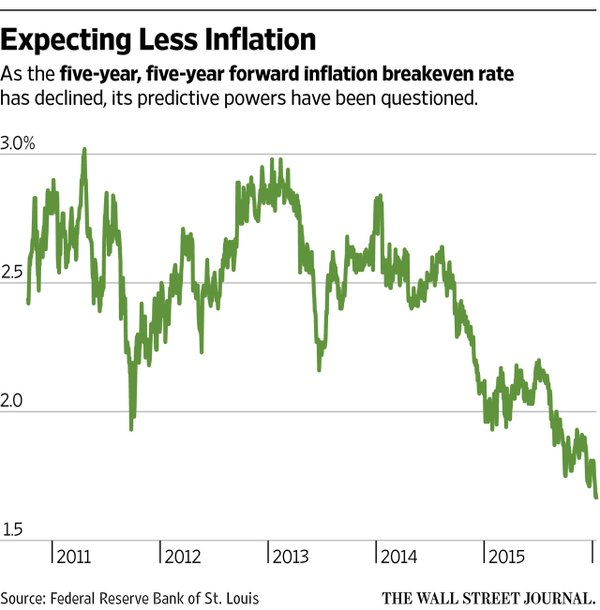

Expecting less inflation

Here is the associated WSJ article. Yes oil is down and the Fed did a slight rate hike, but still the broader lesson is that we are moving into economic corridors we do not understand. I don’t know that any theory has done a good job predicting inflation dynamics. Wages are showing (finally) some very modest growth, so the “we were in a liquidity trap, deflation was delayed because wages are sticky, finally wage are falling” explanation also seems wrong. I also don’t think we will be seeing another Fed rate hike anytime soon.

Thursday assorted links

1. The Council of Psychological Advisers.

2. Do not put Q-tips in your ears.

3. Thrillers and noir novels with economics.

4. Caveat emptor: Glenn Loury, Ann Althouse, and Donald Trump.

5. Michel Tournier has passed away, NYT here. Friday was my favorite novel of his, and it was his first novel which he published at the age of 43.

Too Good to Be True

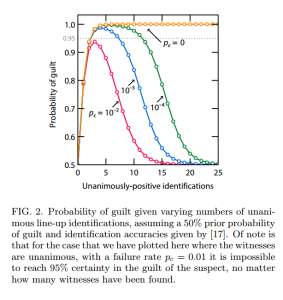

In ancient Israel a court of 23 judges called the Sanhedrin would decide matters of importance such as death penalty cases. The Talmud prescribes a surprising rule for the court. If a majority vote for death then death is imposed except, “If the Sanhedrin unanimously find guilty, he is acquitted.” Why the peculiar rule?

In an excellent new paper, Too Good to Be True, Lachlan J. Gunn et al. show that more evidence can reduce confidence. The basic idea is simple. We expect that in most processes there will normally be some noise so absence of noise suggests a kind of systemic failure. The police are familiar with one type of example. When the eyewitnesses to a crime all report exactly the same story that reduces confidence that the story is true. Eyewitness stories that match too closely suggests not truth but a kind a systemic failure, namely the witnesses have collaborated on telling a lie.

What Gunn et al. show is that the accumulation of consistent (non-noisy) evidence can reverse one’s confidence surprisingly quickly. Consider a police lineup but now consider a more likely cause of systemic failure than witness conspiracy. Suppose that there is a small probability, say 1%, that the police arrange the lineup, either on purpose or by accident, so that the “suspect” is the only one who is close to matching the description of the criminal. Now consider what happens to our rational (Bayesian) probability that the suspect is guil

What Gunn et al. show is that the accumulation of consistent (non-noisy) evidence can reverse one’s confidence surprisingly quickly. Consider a police lineup but now consider a more likely cause of systemic failure than witness conspiracy. Suppose that there is a small probability, say 1%, that the police arrange the lineup, either on purpose or by accident, so that the “suspect” is the only one who is close to matching the description of the criminal. Now consider what happens to our rational (Bayesian) probability that the suspect is guil ty as the number of eyewitnesses saying “that’s the guy” increases. The first eyewitness to identify the suspect increases our confidence that the suspect is guilty and our confidence increases when the second and third eyewitness corroborate but when a fourth eyewitness points to the same man our rational confidence should actually

ty as the number of eyewitnesses saying “that’s the guy” increases. The first eyewitness to identify the suspect increases our confidence that the suspect is guilty and our confidence increases when the second and third eyewitness corroborate but when a fourth eyewitness points to the same man our rational confidence should actually

decrease.

Even though the systemic failure rate is only 1%, that small probability starts to weigh more heavily the more consistent (less noisy) the evidence becomes. The red line in the graph at right shows–using a 1% systemic failure rate and realistic probabilities of eyewitness identification–that after 3 witnesses more evidence decreases our confidence and when more than 10 witnesses identify the same suspect we should be less certain of guilt than when one witness identifies the suspect! The yellow line shows how certainty increases when there is no possibility of systemic failure which is what most people imagine is the case. Notice from the green line that even when the probability of systemic failure is tiny (.01%) it begins to dominate the results quite early.

What matters is not that the probability of systemic failure is tiny but how it compares to the probability of consistency which, with any reasonable estimate of noise, is itself getting tinier and tinier as evidence accumulates. In another application, the authors show how even the miniscule probability of a stray cosmic ray flipping a bit in machine code can materially reduce our confidence in common cryptographic procedures.

In summary, the peculiar rule of the Talmud receives support from Bayesian analysis–too much consistency is suspect of failure.

*Congress and the Shaping of the Middle East*

That is the new Kirk J. Beattie book, and I find it one of the very best studies on how Washington actually works; I am less interested in the determinants of Middle East policy per se. Here is one bit:

On the Senate side, I got the distinct impression that the constituents are not, in general, as important to senators as they are to House members. One gets the distinct impression that individuals with financial clout are far more likely to get senators’ attention than others. As one staffer put it, “If you’re talking to me, you’re talking about money. People are not coming to these issues for the first time. But for us, where our constituents are is very marginal.” That said, a small number of well-heeled individuals can get senators’ attention in many but certainly not all cases. The bias here runs distinctly in favor of putative supporters of Israel. While other religious or ethno-religious factors are in play, like the size and strength of a senator’s evangelical community, senators appear to be less concerned about these voices, unless of course the senator either shares or sees utility in that perspective. This parallels views held by House staffers, leaving one to think that evangelical senators’ commitment to Israel exceeds the level of pro-Israel concern by the evangelical masses.

Among other virtues, the book offers a new (to me) channel for how money might affect politics. Even if donors cannot “buy positions” from politicians, the need to stay competitive in a more or less zero-sum fundraising game means that Congressional staff do not have enough time to study or learn issues very well, and thus depend all the more on outside sources of information.

Definitely recommended, you can buy it here.

The Austrian theory of the business cycle continues its comeback

Except no one seems interested in calling it by that name. Here is the new NBER working paper by David López-Salido, Jeremy C. Stein, and Egon Zakrajšek, “Credit-Market Sentiment and the Business Cycle”:

Using U.S. data from 1929 to 2013, we show that elevated credit-market sentiment in year t – 2 is associated with a decline in economic activity in years t and t + 1. Underlying this result is the existence of predictable mean reversion in credit-market conditions. That is, when our sentiment proxies indicate that credit risk is aggressively priced, this tends to be followed by a subsequent widening of credit spreads, and the timing of this widening is, in turn, closely tied to the onset of a contraction in economic activity. Exploring the mechanism, we find that buoyant credit-market sentiment in year t – 2 also forecasts a change in the composition of external finance: net debt issuance falls in year t, while net equity issuance increases, patterns consistent with the reversal in credit-market conditions leading to an inward shift in credit supply. Unlike much of the current literature on the role of financial frictions in macroeconomics, this paper suggests that time-variation in expected returns to credit market investors can be an important driver of economic fluctuations.

The paper is here, here are ungated copies. Here are some other related “Austrian” papers.

The resurrection of both Austrian and “risk-based” theories shows how alive and well macro has been of late, but at least in blog land you don’t hear that much about them…

Claims about plastic

If we keep producing (and failing to properly dispose of) plastics at predicted rates, plastics in the ocean will outweigh fish pound for pound in 2050, the non-profit foundation said in a report Tuesday.

According to the report, worldwide use of plastic has increased 20-fold in the past 50 years, and it is expected to double again in the next 20 years. By 2050, we’ll be making more than three times as much plastic stuff as we did in 2014.

Keep in mind those numbers are crude extrapolations. Still, it is not clear what countervailing force would cause the production of plastics to decline. So I suppose Mr. McGuire was right.

Here is the Sarah Kaplan story.

Wednesday assorted links

2. 1987 piece on whether oil prices will hold at $18 a barrel — maybe they will!

3. Writing political speeches by AI algorithm.

4. Classic books, such as Moby-Dick, with only the punctuation.

5. From 2010 to 2014, life expectancy in Syria has fallen from 79.5 to 55.7.

6. What happens when a banking system shuts down? A look at Ireland in the 1970s.

China fact of the day

By almost all measures, China’s $3.3 trillion foreign reserves, the world’s largest, look formidable. Except one.

Compared with the amount of yuan sloshing around in the economy, a proxy for potential capital outflows, China’s firepower seems limited. The dollar reserves account for 15.5 percent of M2, a broad measure of money in circulation. That’s the lowest since 2004 and is less than levels in most Asian economies including Thailand, Singapore, Taiwan, Philippines and Malaysia, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

That is from Ye Xie. Please do note all of the caveats and qualifiers in the longer piece. The claim is not that Chinese reserves are currently in some kind of crisis situation, only that we should not overestimate their import, relative to potential and indeed actual capital outflows.

How to seem telepathic

This is probably one of the most useful things you will learn from MR all year. It is from Maria Konnikova’s new book The Confidence Game:

In 2010, Nicholas Epley and Tal Eyal of Ben-Gurion University published the results of a series of experiments aimed at improving our person and mind perception skills. The title of their paper: “How to Seem Telepathic.” Many of our errors, the researchers found, stem from a basic mismatch between how we analyze ourselves and how we analyze others. When it comes to ourselves, we employ a fine-grained, highly contextualized level of detail. When we think about others, however, we operate at a much higher, more generalized and abstract level. For instance, when answering the same question about ourselves or others — how attractive are you? — we use very different cues. For our own appearance, we think about how our hair is looking that morning, whether we got enough sleep, how well that shirt matches our complexion. For that of others, we form a surface judgment based on overall gist. So, there are two mismatches: we aren’t quite sure how others are seeing us, and we are incorrectly judging how they see themselves.

If, however, we can adjust our level of analysis, we suddenly appear much more intuitive and accurate. In one study, people became more accurate at discerning how others see them when they thought their photograph was going to be evaluated a few months later, as opposed to the same day, while in another, the same accuracy shift happened if they thought a recording they’d made describing themselves would be heard a few months later [TC: recall Robin Hanson’s near vs. far mode]. Suddenly, they were using the same abstract lens that others are likely to use naturally…

Upon reading this passage I realized I have been thinking in these terms for years, without quite realizing it so explicitly.

One implication: if you feel bad one morning, don’t let it get you down and lower your confidence. Other people probably won’t notice your problems.

Another implication: you’ll understand yourself better if, in a given moment, you can pretend to distance yourself from some of your immediate impressions of your day, and treat yourself like a piece of your writing which you set aside for a week so you could look at it fresh.

A third implication is this: you can read other people’s moods better by ignoring some of your overall impressions of them, and by focusing on what they might perceive to be small changes in their situation, appearance, or stress levels.

The original research is here, worth a read (pdf). And here are various reviews of the Konnikova book.

Bad press for Auschwitz price fixing

Now, the Israel Antitrust Authority has announced that nine tour operator executives have been arrested on suspicion of running a secret price-fixing ring that was aimed at artificially inflating the cost of trips to former Nazi death camps such as Auschwitz.

At least six tour operators are being investigated on suspicion of involvement in the alleged cartel. In some cases, the homes of company executives were searched and property confiscated. According to the publication Haaretz, one of those detained is also suspected of bribery.

…The Israeli government had given a number of tour operators the tenders for the business of flying high school students to Poland. In theory, these companies would be in competition: The schools were supposed to negotiate among the companies to find the best deal. The investigation found that in practice, however, the prices appeared to be fixed among the companies. Although the operators appeared to offer discounts to schools, investigators say, these discounts were secretly coordinated and there was no real competition.

That is from Adam Taylor, via Otis Reid.