Month: July 2020

Fight the Virus! Please.

One of the most confounding aspects of the pandemic has been Congress’s unwillingness or inability to spend to fight the virus. As I said in the LA Times:

If an invader rained missiles down on cities across the United States killing thousands of people, we would fight back. Yet despite spending trillions on unemployment insurance and relief to deal with the economic consequences of COVID-19, we have spent comparatively little fighting the virus directly.

Economists Steven Berry and Zack Cooper have run the numbers:

By our calculations, less than 8 percent of the trillions in funding that Congress has allocated so far in response to the virus has been for solutions that would shorten or mitigate the virus itself: measures like increasing the supply of PPE, expanding testing, developing treatments, standing up contact tracing, or developing a vaccine. A case in point is the most recent House Covid-19 package. It calls for $3 trillion in spending; less than 3 percent of that total is allocated toward Covid testing. As Congress considers next steps, it’s imperative to shift priorities and direct more funding and effort toward actually ending the pandemic.

Berry and Copper point to the vaccine plan that I am working on as an example of smart spending:

…a group of prominent economists, including Nobel Laureate Michael Kremer, has proposed spending a $70 billion dollar vaccine effort. The proposed expenditure is both much larger than anything proposed by the White House or Congress and also quite cheap compared to the potential benefits.

…[Similarly] Nobel Laureate Paul Romer and the Rockefeller Foundation have each sketched out $100 billion plans to increase testing. We say: Let’s fund both, allocating half the funds directly to states, who can spend to activate the vast capacity of university labs, and also fund Romer’s plan to scale up $10 instant tests for true mass testing. We could create a $50 billion dollar challenge prize that rewards the first 10 firms that develop effective treatments for Covid-19 — $5 billion each. We could fund Scott Gottlieb and Andy Slavitt’s bipartisan $50 billion contact tracing proposal. We could allocate $100 billion to fund the libertarian leaning Mercatus Center’s proposal for advanced purchase contracts to procure massive quantities of PPE.

What makes this all the more confounding is that spending to defeat the virus will more than pay for itself! As I said in my piece in the Washington Post (with ):

Economists talk about “multipliers” — an injection of spending that causes even larger increases in gross domestic product. Spending on testing, tracing and paid isolation would produce an indisputable and massive multiplier effect.

Who gains by killing the economy and letting people die? Yes, it’s possible to spin some elaborate conspiracy about someone, somewhere benefiting. But in talking with people in Congress the message I hear is not that there’s a secret cabal with a special interest in economic collapse and dying constituents. In a way, the message is worse. Multiple people have told me that things move slowly, no one is stepping up to the plate, leadership is absent. “Who is John Galt?,” they sigh. Ok, they don’t literally say that, but that sigh of resignation is what it feels like in the United States today at the highest levels of government.

Rereading Ayn Rand on the New Left

It used to be called The New Left: The Anti-Industrial Revolution, but the later title was Return of the Primitive. It was published in 1971, but sometimes drawn from slightly earlier essays. I wondered if a revisit might shed light on the current day, and here is what I learned:

1. “The New Left is the product of cultural disintegration; it is bred not in the slums, but in the universities; it is not the vanguard of the future, but the terminal stage of the past.”

2. The moderates who tolerate the New Left and its anti-reality bent can be worse than the New Left itself.

3. Ayn Rand wishes to cancel the New Left, albeit peacefully.

4. “Like every other form of collectivism, racism is a quest for the unearned.” Ouch, it would be good to resuscitate this entire essay (on racism).

5. She fears the collapse of Europe into tribalism, racism, and balkanization. I am not sure if I should feel better or worse about the ongoing persistence of this trope.

6. It is easy to forget that English was not her first language: “Logical Positivism carried it further and, in the name of reason, elevated the immemorial psycho-epistemology of shyster lawyers to the status of a scientific epistemological system — by proclaiming that knowledge consists of linguistic manipulations.”

6b. Kant was the first hippie.

7. The majority of people do not hate the good, although they are disgusted by…all sorts of things.

8. Like many Russian women, she is skeptical of the American brand of feminism: “As a group, American women are the most privileged females on earth: they control the wealth of the United States — through inheritance from fathers and husbands who work themselves into an early grave, struggling to provide every comfort and luxury for the bridge-playing, cocktail-party-chasing cohorts, who give them very little in return. Women’s Lib proclaims that they should give still less, and exhorts its members to refuse to cook their husbands’ meals — with its placards commanding “Starve a rat today!”” Feminism for me, but not for thee, you could call it.

Overall I would describe this as a bracing reread. But what struck me most of all was how much the “Old New Left” — whatever you think of it — had more metaphysical and ethical and aesthetic imagination — than the New New Left variants running around today. As Rand takes pains to point out (to her dismay), the Old New Left did indeed have Woodstock, which in reality was not as far from the Apollo achievement as she was suggesting at the time.

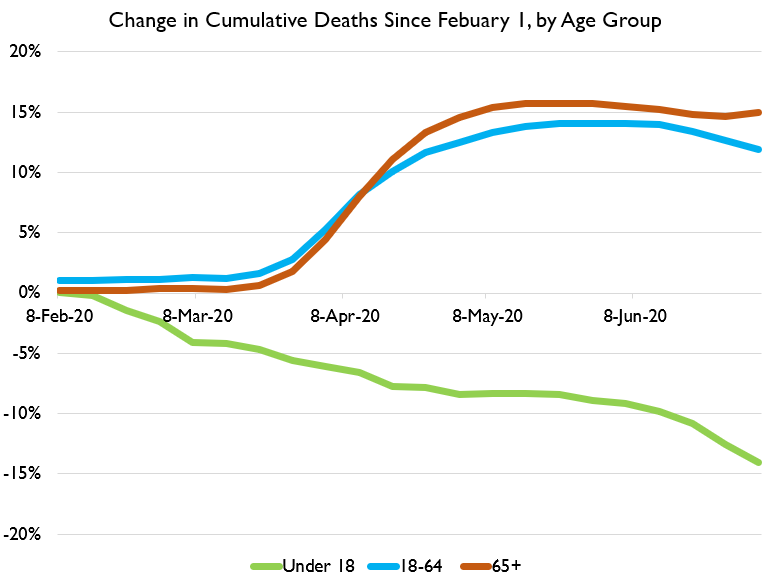

Excess deaths are down — below average — for those younger than eighteen

In the United States that is, link here, from Lyman Stone, photo here:

In other words, lockdown and shelter at home have limited some of the otherwise risky activities that young people engage in.

In other words, lockdown and shelter at home have limited some of the otherwise risky activities that young people engage in.

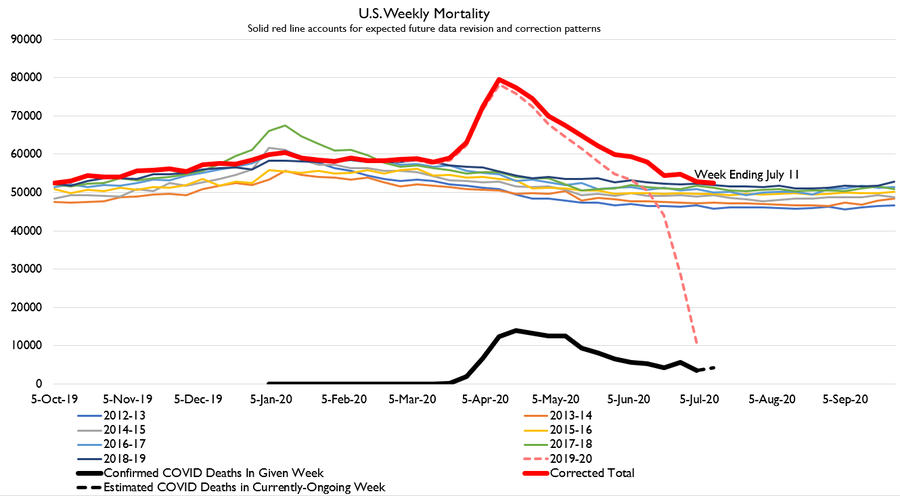

Excess deaths more generally seem to have reached a normal range, albeit at the upper end of that range:

I wouldn’t want to call this “good news,” but it is one form of putting the current situation into perspective.

I wouldn’t want to call this “good news,” but it is one form of putting the current situation into perspective.

Friday assorted links

Claims about turkeys

You know, turkeys sound a lot like aliens, if you just name them part by part.

“Anatomical structures on the head and throat of a domestic turkey. 1. Caruncles, 2. Snood, 3. Wattle (Dewlap), 4. Major caruncle, 5. Beard”

That is from Jackson Stone.

The arrival of cheap food in England

The period from the 1870s to the start of the First World War saw a steep rise in working-class living standards in Britain, much of it underpinned by a vast array of cheap imported foods. Thanks to new refrigerated steamships and a growing railway network, such items as butter, eggs and meat could be transported from as far afield as New Zealand and Argentina. The British started to eat butter from Denmark; oranges and grapes from Spain; mutton from Argentina; bacon and cheese from the United States; wheat from Canada. The percentage of meat consumed in Britain that was imported rose from 13.6 per cent in 1872 to 42.3 per cent in 1912. The influx of these new cheap food imports gave many in the working classes a much more varied and tasty diet than before. Eggs were no longer a luxury and as the price of imported fruit fell, many in the cities started eating oranges and bananas for the first time. They could only afford to buy these foods because the costers who sold them kept the prices too low to allow themselves a decent life. By the same token, big shopkeepers kept food prices down by forcing employees to work long hours for low pay. A ninety-hour week was not uncommon for a clerk in a Victorian grocer shop, but these hours still might not deliver a wage large enough to live on, despite the cheapness of food.

Here is more from Bee Wilson, via The Browser.

The polity that is Oklahoma

The Supreme Court on Thursday ruled that nearly half of Oklahoma falls within an Indian reservation, a decision that could reshape the criminal-justice system by preventing state authorities from prosecuting offenses there that involve Native Americans.

The 5-to-4 decision, potentially one of the most consequential legal victories for Native Americans in decades, could have far-reaching implications for the 1.8 million people who live across what is now deemed “Indian Country” by the high court. The lands include much of Tulsa, Oklahoma’s second-biggest city.

The case was steeped in the United States government’s long history of brutal removals and broken treaties with Indigenous tribes, and grappled with whether lands of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation had remained a reservation after Oklahoma became a state.

Here is the full NYT article. Do those people now live under some kind of joint sovereignty?

The New Yorker covers the Scott Alexander saga

Thursday assorted links

1. Thor Heyderdahl vindicated (NYT).

2. Just a bit more distancing and Sweden suddenly fell to 17 deaths per week?

3. Heterogeneities in who is most vulnerable, amazing data set (NYT). Original research is here.

4. Ross Douthat thread on free speech and coalitions.

5. They are solving for the equilibrium: “NYPD limits retirement applications amid 400 percent surge this week.“

Pooled Testing is Super-Beneficial

Tyler and I have been pushing pooled testing for months. The primary benefit of pooled testing is obvious. If 1% are infected and we test 100 people individually we need 100 tests. If we split the group into five pools of twenty then if we’re lucky, we only need five tests. Of course, chances are that there will be some positives in at least one group and taking this into account we will require 23.2 tests on average (5 + (1 – (1 – .01)^20)*20*5). Thus, pooled testing reduces the number of needed tests by a factor of 4. Or to put it the other way, under these assumptions, pooled testing increases our effective test capacity by a factor of 4. That’s a big gain and well understood.

An important new paper from Augenblick, Kolstad, Obermeyer and Wang shows that the benefits of pooled testing go well beyond this primary benefit. Pooled testing works best when the prevalence rate is low. If 10% are infected, for example, then it’s quite likely that all five pools will have at least one positive test and thus you will still need nearly 100 tests (92.8 expected). But the reverse is also true. The lower the prevalence rate the fewer tests are needed. But this means that pooled testing is highly complementary to frequent testing. If you test frequently then the prevalence rate must be low because the people who tested negative yesterday are very likely to test negative today. Thus from the logic given above, the expected number of tests falls as you tests more frequently (per test-cohort).

Suppose instead that people are tested ten times as frequently. Testing individually at this frequency requires ten times the number of tests, for 1000 total tests. It is therefore natural think that group testing also requires ten times the number of tests, for more than 200 total tests. However, this estimation ignores the fact that testing ten times as frequently reduces the probability of infection at the point of each test (conditional on not being positive at previous test) from 1% to only around .1%. This drop in prevalence reduces the number of expected tests – given groups of 20 – to 6.9 at each of the ten testing points, such that the total number is only 69. That is, testing people 10 times as frequently only requires slightly more than three times the number of tests. Or, put in a different way, there is a “quantity discount” of around 65% by increasing frequency.

Peter Frazier, Yujia Zhang and Massey Cashore also point out that you could also do an array-protocol in which each person is tested twice but in two different groups–this doubles the number of initial tests but limits the number of false-positives (both tests must be positive) and the number of needed retests. (See figure.).

Moreover, we haven’t yet taken into account the point of testing which is to reduce the prevalence rate. If we test frequently we can reduce the prevalence rate by quickly isolating the infected population and by reducing the prevalence rate we reduce the number of needed tests. Indeed, under some parameters it’s possible to increase the frequency of testing and at the same time reduce the total number of tests!

We can do better yet if we group individuals whose risks are likely to be correlated. Consider an office building with five floors and 100 employees, 20 per floor. If the prevalence rate is 1% and we test people at random then we will need 23.2 tests on average, as before. But suppose that the virus is more likely to transmit to people who work on the same floor and now suppose that we pool each floor. Holding the total prevalence rate constant, we are now likely to have a zero prevalence rate on four floors and a 5% prevalence rate on one floor. We don’t know which floor but it doesn’t matter–the expected number of tests required now falls to 17.8.

The authors suggest using machine learning techniques to uncover correlations which is a good idea but much can be done simply by pooling families, co-workers, and so forth.

The government has failed miserably at controlling the pandemic. Tens of thousands of people have died who would have lived under a more competent government. The FDA only recently said they might allow pooled testing, if people ask nicely. Unbelievably, after telling us we don’t need masks (supposedly a noble lie to help limit shortages), the CDC is still disparaging testing of asymptomatic people (another noble lie?) which is absolutely disastrous. Paul Romer is correct, testing capacity won’t increase until we put soft drink money behind advance market commitments and start using techniques such as pooled testing. Fortunately or sadly, depending on how you look at it, it’s not too late to do better. Some universities are now proposing rapid, frequent testing using pooling. Harvard will test every three days. Cornell will test frequently. Delaware State will test weekly. Lets hope the idea spreads from the ivory tower.

A highly qualified reader emails me on heterogeneity

I won’t indent further, all the rest is from the reader:

“Some thoughts on your heterogeneity post. I agree this is still bafflingly under-discussed in “the discourse” & people are grasping onto policy arguments but ignoring the medical/bio aspects since ignorance of those is higher.

Nobody knows the answer right now, obviously, but I did want to call out two hypotheses that remain underrated:

1) Genetic variation

This means variation in the genetics of people (not the virus). We already know that (a) mutation in single genes can lead to extreme susceptibility to other infections, e.g Epstein–Barr (usually harmless but sometimes severe), tuberculosis; (b) mutation in many genes can cause disease susceptibility to vary — diabetes (WHO link), heart disease are two examples, which is why when you go to the doctor you are asked if you have a family history of these.

It is unlikely that COVID was type (a), but it’s quite likely that COVID is type (b). In other words, I expect that there are a certain set of genes which (if you have the “wrong” variants) pre-dispose you to have a severe case of COVID, another set of genes which (if you have the “wrong” variants) predispose you to have a mild case, and if you’re lucky enough to have the right variants of these you are most likely going to get a mild or asymptomatic case.

There has been some good preliminary work on this which was also under-discussed:

- NEJM paper studied Italy and Spain and found that genes controlling blood type predicted disease severity. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2020283 (NIH director had a blog post about it with layperson’s explanation here https://directorsblog.nih.gov/2020/06/18/genes-blood-type-tied-to-covid-19-risk-of-severe-disease/)

- NYTimes covered a follow-up paper showing that this varies by ethnicity, and in particular ~60% of South Asians carry these genes compared to only 4% of East Asians and almost no Africans. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/04/health/coronavirus-neanderthals.html

You will note that the majority of doctors/nurses who died of COVID in the UK were South Asian. This is quite striking. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/08/world/europe/coronavirus-doctors-immigrants.html — Goldacre et al’s excellent paper also found this on a broader scale (https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.05.06.20092999v1). From a probability point of view, this alone should make one suspect a genetic component.

There is plenty of other anecdotal evidence to suggest that this hypothesis is likely as well (e.g. entire families all getting severe cases of the disease suggesting a genetic component), happy to elaborate more but you get the idea.

Why don’t we know the answer yet? We unfortunately don’t have a great answer yet for lack of sufficient data, i.e. you need a dataset that has patient clinical outcomes + sequenced genomes, for a significant number of patients; with this dataset, you could then correlate the presences of genes {a,b,c} with severe disease outcomes and draw some tentative conclusions. These are known as GWAS studies (genome wide association study) as you probably know.

The dataset needs to be global in order to be representative. No such dataset exists, because of the healthcare data-sharing problem.

2) Strain

It’s now mostly accepted that there are two “strains” of COVID, that the second arose in late January and contains a spike protein variant that wasn’t present in the original ancestral strain, and that this new strain (“D614G”) now represents ~97% of new isolates. The Sabeti lab (Harvard) paper from a couple of days ago is a good summary of the evidence. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.07.04.187757v1 — note that in cell cultures it is 3-9x more infective than the ancestral strain. Unlikely to be that big of a difference in humans for various reasons, but still striking/interesting.

Almost nobody was talking about this for months, and only recently was there any mainstream coverage of this. You’ve already covered it, so I won’t belabor the point.

So could this explain Asia/hetereogeneities? We don’t know the answer, and indeed it is extremely hard to figure out the answer (because as you note each country had different policies, chance plays a role, there are simply too many factors overall).

I will, however, note that this the distribution of each strain by geography is very easy to look up, and the results are at least suggestive:

- Visit Nextstrain (Trevor Bedford’s project)

- Select the most significant variant locus on the spike protein (614)

- This gives you a global map of the balance between the more infective variant (G) and the less infective one (D) https://nextstrain.org/ncov/global?c=gt-S_614

- The “G” strain has grown and dominated global cases everywhere, suggesting that it really is more infective

- A cursory look here suggests that East Asia mostly has the less infective strain (in blue) whereas rest of the world is dominated by the more infective strain:

-

– Compare Western Europe, dominated by the “yellow” (more infective) strain:

You can do a similar analysis of West Coast/East Coast in February/March on Nextstrain and you will find a similar scenario there (NYC had the G variant, Seattle/SF had the D).

Again, the point of this email is not that I (or anyone!) knows the answers at this point, but I do think the above two hypotheses are not being discussed enough, largely because nobody feels qualified to reason about them. So everyone talks about mask-wearing or lockdowns instead. The parable of the streetlight effect comes to mind.”

The Harpers free speech letter and controversy

Many of you have been asking for a more detailed account of what I think. Here is an NYT summary of the debate, in case you have been living under a rock. Of course I side with those who signed the letter, but I would add a few points.

First, I don’t think the letter itself quite pinpoints what has gone wrong, nor do I think that such a collective project is likely to do so. Most of us would agree there is nothing wrong per se with voluntary standards of affiliation, or voluntary speech regulations in private institutions, nor should the NYT feel obliged to turn its platforms over to tyrants such as…say…Vladimir Putin.

The actual problem is that we have a new bunch of “speech regulators” (not in the legal sense, not usually at least) who are especially humorless and obnoxious and I would say neurotic — in the personality psychology sense of that word. I say let’s complain about the real problem, namely the moral fiber, emotional temperaments, and factual worldviews of the individuals who have arrogated the new speech censorship functions to themselves. I am free to raise that charge, a collective letter signed by 153 diverse intellectuals and artists really is not, and is strongly constrained toward the more “positive” and “constructive” approaches to the problem, or at least what might appear to be such.

The letter is descriptively accurate in blaming lack of “toleration” and increased “censoriousness” for our problems, but those words only make sense if you have a much deeper mental model of what is actually going on. There is ultimately something question-begging about words that do not pin down the proper margin of objection, or what might be a correct worldview, or what might be a worldview we should in fact not tolerate in our affiliations. In other words, a non-question-begging answer has to take sides to some extent, and that is especially hard for a collective or grand coalition to do.

That is fine! No complaint from these quarters, and I am very glad they took the trouble to move forward with this project. I know many of the signers, and those individuals I like, admire, and respect, to a person. But in reality, the letter itself, de facto, decided to elevate consensus and reputational oomph over actual free speech about the real truths in our world.

So in the Straussian sense it is actually a letter about the limits and impotence of true free speech, and the need to be constrained by social consensus.

How about the signers and non-signers? Here is from the NYT piece:

“We’re not just a bunch of old white guys sitting around writing this letter,” Mr. Williams, who is African-American, said. “It includes plenty of Black thinkers, Muslim thinkers, Jewish thinkers, people who are trans and gay, old and young, right wing and left wing.”

Only a very small number of individuals in the world even had the option of signing, and it seems the particular individuals chosen were selected with an eye toward their public and intellectual palatability. Do you really think they would have invited [fill in the blank with name of “evil” person of your choice] to sign? Or how about such a letter signed only by white males? More prosaically, how about a few vocal Trump supporters or members of the IDW?

You can’t expect readers to scroll through thousands of names, but of course with internet technology you could have a linked pdf with a second tier of signers, more numerous and also more truly intellectually diverse. The de facto message seems to be: “free speech is too important a cause to let just anybody sign onto.”

Again, what they did is fine! I work with voluntary institutions all the time, and am quite familiar with “how things have to go.”

But again, let’s be honest. To produce a paean to free speech, acceptable to Harper’s and worthy of receiving a non-condemnatory article in The New York Times, the organizers had to “restrict free speech” in a manner not altogether different than what they are objecting to.

Fortunately, most people will read the Harper’s letter straight up rather than in Straussian terms. The Straussian reading is far more depressing than the pleasure you might feel at seeing this missive take center stage, if only for a day.

Wednesday assorted links

1. “Prisoners have long used contraband cellphones to pull off all manner of scams from the inside. But in attempting to build and sell a house from behind bars, Murray allegedly took things to a new level of sophistication.” Link here, recommended.

2. Charlie Songhurst is one of the smartest people I know. Podcast with him, recommended.

3. Acoustic levitation of objects inside your body.

4. How did Helen DeWitt and Andrew Gelman end up co-authoring a piece? I’d like to read another piece on that, it could be co-authored by them too.

5. Blindsight.

6. Is the dam starting to break? (but in which direction?) And “I am so sorry.” And another retraction. And more. Egads, and A+.

7. War over being nice. Wordy at first, but an important attempt, recommended.

Sweden fact of the day

Cases in the Nordic country have declined sharply over the past few days and on Tuesday only 283 new cases were recorded.

That contrasts with a torrid month of June when daily numbers ran as high as 1,800, eclipsing rates across much of Europe, even as deaths and hospitalisations continued to decline from peaks in April.

At the same time:

…weekly numbers for tests have more than doubled since late May, putting the country in the same bracket as extensively testing nations such as Germany.

Here is the full article. Who again has the best model of this? Anyone? How about no one? Here is a NYT piece on Sweden, dated July 7, it doesn’t even mention any of this.

Here is the steadily declining Swedish death rate. No need to point out that Denmark and Norway, with their early and swift responses, did much better yet. I am interested in what is the best way to model why Sweden is not doing much worse.

Tuesday assorted links

1. Older people are less pessimistic about the health risks of Covid-19.

5. How the police think, good and highly relevant piece.

6. New criticism of the relevance of the T-cell immunity factor.