Month: November 2020

Why is bitcoin at $18,000?

We can all admit now that it isn’t a bubble, right? Of course you still might think the current price is too high, as returns are a (near) random walk.

This WSJ article ably surveys the current landscape. I put the least stock on “inflation hedge” arguments, and the most on ordinary factors such as these:

In October, PayPal Holdings Inc. PYPL 4.23% unveiled a service that allows its users to buy and sell bitcoin directly in their accounts. It became available to all U.S. users on Nov. 12 and will expand to Venmo and some international markets next year.

You don’t have to believe that PayPal per se is moving the market. Rather the normalization of bitcoin raises the ongoing probability that it will become a normal albeit small part of various financial and corporate portfolios. And that in turn raises its equilibrium value. The mere continuing existence of bitcoin — illustrating that it won’t disappear anytime soon — can have a broadly similar effect.

The Flat Tax Increases Growth

There is something to be said for tearing it all down and starting again. The flat tax, for example, has long been debated but has never been fully adopted in the United States. After the end of communism, however, many countries in Eastern Europe and Central Asia adopted flat taxes. Brian Wheaton, on the market from Harvard, has a very nice paper which, somewhat surprisingly, is one of the first to really dig into this series of natural experiments.

Between 1994 and 2011,twenty post-communist countries introduced such a tax at varying—but typically quite low—rates as a percentage of income.At their peak, nearly all Eastern European and Central Asian countries had a flat tax in effect.Since 2011, on the other hand, some of these countries have repealed their flat taxes and reverted to a progressive system of income taxation.These policy changes represent an ideal natural experiment through which to test the multitude of claims pertaining to flat taxation.

Using quarterly GDP data on this panel of flat-tax adopters and a difference-in-differences identification strategy, I find that the adoption of a flat tax structure has a strongly significant positive effect of 1.36 percentage points on GDP growth…[lasting about a decade].

Wheaton finds that it wasn’t just lower average tax rates which mattered, holding average rates constant a flatter tax-structure also led to more capital investment and moderately greater labor supply.

Wheaton has many other interesting papers.

Do pandemics boost public faith in science?

No, according to Barry Eichengreen, Cevat Giray Aksoy, and Orkun Saka:

It is sometimes said that an effect of the COVID-19 pandemic will be heightened appreciation of the importance of scientific research and expertise. We test this hypothesis by examining how exposure to previous epidemics affected trust in science and scientists. Building on the “impressionable years hypothesis” that attitudes are durably formed during the ages 18 to 25, we focus on individuals exposed to epidemics in their country of residence at this particular stage of the life course. Combining data from a 2018 Wellcome Trust survey of more than 75,000 individuals in 138 countries with data on global epidemics since 1970, we show that such exposure has no impact on views of science as an endeavor but that it significantly reduces trust in scientists and in the benefits of their work. We also illustrate that the decline in trust is driven by the individuals with little previous training in science subjects. Finally, our evidence suggests that epidemic-induced distrust translates into lower compliance with health-related policies in the form of negative views towards vaccines and lower rates of child vaccination.

Here is the link to the NBER working paper.

The case for geographically concentrated vaccine doses

Here goes:

A central yet neglected point is that vaccines should not be sent to each and every part of the U.S. Instead, it would be better to concentrate distribution in a small number of places where the vaccines can have a greater impact.

Say, for the purposes of argument, that you had 20,000 vaccine doses to distribute. There are about 20,000 cities and towns in America. Would you send one dose to each location? That might sound fair, but such a distribution would limit the overall effect. Many of those 20,000 recipients would be safer, but your plan would not meaningfully reduce community transmission in any of those places, nor would it allow any public events to restart or schools to reopen.

Alternatively, say you chose one town or well-defined area and distributed all 20,000 doses there. Not only would you protect 20,000 people with the vaccine, but the surrounding area would be much safer, too. Children could go to school, for instance, knowing that most of the other people in the building had been vaccinated. Shopping and dining would boom as well.

Here is one qualifier, but in fact it pushes one further along the road to geographic concentration:

Over time, mobility, migration and mixing would undo some of the initial benefits of the geographically concentrated dose of vaccines. That’s why the second round of vaccine distribution should go exactly to those people who are most likely to mix with the first targeted area. This plan reaps two benefits: protecting the people in the newly chosen second area, and limiting the ability of those people to disrupt the benefits already gained in the first area.

In other words, if the first doses went (to choose a random example) to Wilmington, Delaware, the next batch of doses should go to the suburbs of Wilmington. In economics language [behind this link is a highly useful Michael Kremer paper], one can say that Covid-19 infections (and protections) have externalities, and there are increasing returns to those externalities. That implies a geographically concentrated approach to vaccine distribution, whether at the federal or state level.

Here is another qualifier:

…there will be practical limits on a fully concentrated geographic distribution of vaccines. Too many vaccines sent to too few places will result in long waits and trouble with storage. Nonetheless, at the margin the U.S. should still consider a more geographically concentrated distribution than what it is likely to do.

Do you think that travel restrictions have stopped the spread of the coronavirus? (Doesn’t mean you have to favor them, all things considered.) Probably yes. If so, you probably ought to favor a geographically concentrated initial distribution of the vaccine as well — can you see why it is the same logic? Just imagine it spreading out like stones on a Go board.

Of course we are not likely to do any of this. Here is my full Bloomberg column.

The pandemic is indeed a big deal

In our estimation, and with standard preference parameters, the value of the ability to end the pandemic is worth 5-15% of total wealth. This value rises substantially when there is uncertainty about the frequency and duration of pandemics. Agents place almost as much value on the ability to resolve the uncertainty as they do on the value of the cure itself.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Viral V. Acharya, Timothy Johnson, Suresh Sundaresan, and Steven Zheng. Their analysis also shows that preventing or limiting future pandemics may be a bigger deal yet.

Monday assorted links

1. Short video, Beijing residents on Biden and Trump. They are better thinkers than the lot of you.

2. Worthwhile Canadian moose car-licking warnings. And new Jordan Peterson book coming in March.

3. Other coronavirus variants found in frozen bats outside of China.

5. Rolf is wrong again. And yet another dispute. And French students who talk about their teachers (NYT). They send the police, that is what they do.

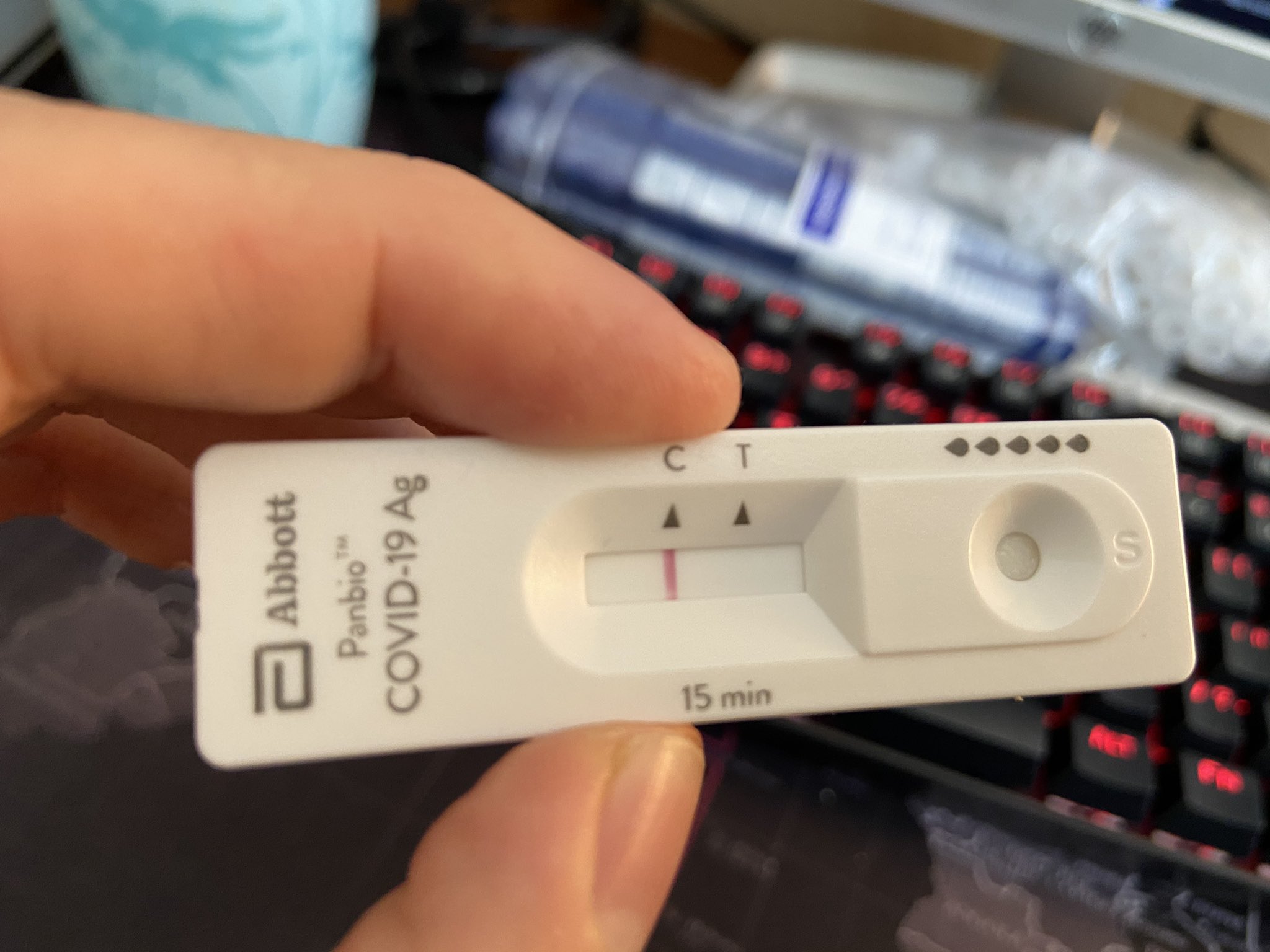

Rapid Antigen Tests in Europe

Why are these tests important? The CDC now says that asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic people account for a majority of infections. Do you get it? How many people without symptoms will get a COVID PCR test, which can be time consuming and expensive? (And how many PCR tests can we run in a timely fashion if people without symptoms get many more tests?) Not that many. But many people without symptoms would get a $8 or less, at-home, 15 minute test. And if some of those people discover that they are infectious and self-isolate for a few days we can drive infection rates down.

We should have had an Operation Warp Speed for tests. We still need funding for a mass rollout and, of course, the FDA needs to approve these tests! (Here is Michael Mina in Time fulminating at the FDA holdup.)

By the way, more than 2800 Americans have died of COVID since Pfizer requested an Emergency Use Authorization for their vaccine. The FDA meets Dec. 10.

Addendum: Here’s me explaining why Frequent, Fast, and Cheap is Better than Sensitive and the difference between infected and infectious.

Externalities and Covid

I am getting a little ornery with all of the people citing Covid externalities, and then not going a step deeper. To be clear, I agree we should subsidize preventive measures (most of all vaccines and testing, but more too), and close down high-risk indoor gatherings in many locales. No more Democratic Party fundraisers in New York State, not indoors at least.

What is being neglected is that many of the American people are voting with their feet when it comes to externalities, and we may not always like the answers we are seeing. Take all of the pending Thanksgiving travel — the biggest risk is to parents and grandparents, but mostly they are receiving their children voluntarily. Now I get that there is a higher-order risk to friends of the parents and grandparents, and that externality is not internalized, but still…much of the externality is in fact internalized.

I haven’t seen many (any?) jurisdictions in this country where the median voter wants to shut down Thanksgiving travel. Do please note it is in fact my personal preference that no one travel for Thanksgiving, but I’m not going to confuse that preference with the Coasean outcome or for that matter the democratic outcome. It might be the Coasean outcome in northern Jutland, it does not seem to be here.

Or consider mobility. The people of means I know have been moving to Austin and Miami, two locales that are both quite open in the sense of having relatively few Covid-related restrictions on commerce. These individuals do not have to work as a cashier in the Safeway, and so they can enjoy the openness while avoiding most of the corresponding risk. They can work at home and socialize outside. Maybe the weather, the time zone, the “coolness” of the locale, and other factors are more important than the stores being open. Still, the “loose” Covid policies have not scared them away.

One might expect that front-line workers would be less keen to move to Austin and Miami, but I have not seen data to that effect and I am not convinced that is true on net. I genuinely would like to know, and in the meantime am agnostic on the question.

I don’t see many people moving into Vermont or San Francisco, two locales that have done a good job minimizing Covid risk.

Analytically, you might put it this way. There always have been positive externalities from human contact through commerce, and at the margin, even with Covid risk, for many people those externalities still are positive. Thus if you limit or tax those interactions, the policies will be unpopular.

I genuinely do think many of our failings are those of prudence rather than externalities. That is one reason why I am reluctant to recommend large-scale coercive lockdowns, while still regarding the positive fight against Covid with extreme urgency. Three of our prudence failings are the following:

1. We are not good at intertemporal substitution in this context, and

2. The risks of Covid are sufficiently stressful that many people instead prefer to self-deceive and minimize the risks, rather than deal with the stress (NB: this is one instance where higher stakes and decisive choice lead to a worse rather than a better outcome, contra Caplan).

3. Many individuals are bad at grasping the multi-week reporting lags and also the “Blitzkrieg” nature of the struggle.

I am reluctant to smush together the externalities argument and the paternalism argument for policy activism, and instead prefer to unpack the two, even though that weakens the case for major restrictions. It disturbs me that few public health commentators or for that matter commenting economists are willing to consider even this simple analytic division. Talking about all the deaths does not in fact settle the matter, as it remains necessary to ask what Americans really want, and how much we ought to be willing to respect those preferences.

Vaccination economic resumption sentences to ponder

If you think of state governments as basically being as permissive as possible consistent with not overwhelming their hospital systems then even vaccinating 20% of the population has a huge economic impact as long as it’s targeted in a halfway plausible way.

That is from Matt Yglesias. I would stress also the bad news that in the meantime many Americans (other citizens too!) are becoming infected. I haven’t seen recent serological results, but quite some time ago the range already was 10-15% of America infected. It seems entirely plausible to think that many parts of the country (not SF, not Vermont) will be at 30% or higher infected by February. Plus 20% getting vaccinated, and still likely a residue of the population with above average protective immune response, and by that I mean relative to age group.

So overalI I am more optimistic about the spring than are many of the people I am talking to. And the United States may well be the first country to arrive at a semblance of herd immunity, albeit not the way we might have preferred.

Sunday assorted links

1. 40 labs in 21 states (SalivaDirect update).

2. “One travel job that is booming during the pandemic is pet delivery specialist.”

3. Nanobots and mini-binders against Covid (NYT).

4. Kingmakers.

5. Short history of India Pakistan economic growth.

6. Volunteer data heroes of Covid (Bloomberg).

I guess we will learn something from this experiment

Hong Kong will give a one-time HK$5,000 ($645) payment to anyone in the city who tests positive for Covid-19 to encourage people to take tests for the virus, Health Secretary Sophia Chan said.

Here is the full Bloomberg report, via Jackson.

Favorite books by female authors

Elena Ferrante named her top forty, and I am not sure I approve of the exercise at all. Still, here are my top twenty, in no particular order, fiction only, not counting poetry:

1.Lady Murasaki, Tale of Genji.

2. Emily Brontë, Wuthering Heights.

3. Alice Munro, any and all.

4. Elena Ferrante, the Neapolitan quadrology.

5. Doris Lessing, The Golden Notebook.

6. Octavia Butler, Xenogenesis trilogy.

7. Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God.

8. Mary Shelley, Frankenstein.

9. Sigrid Undset, Kristin Lavransdatter.

10. Susanna Clarke, Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell.

11. Virginia Woolf, many.

12. Willa Cather, My Antonia.

13. Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

14. Jane Austen, Persuasion.

15. Anne Rice, The Witching Hour, and #2 in the vampire series.

16. Anaïs Nin? P.D.James? A general award to the mystery genre?

17. Christa Wolf, Cassandra.

18. Marguerite Yourcenar, Memoirs of Hadrian.

19. Irene Nemirovsky, Suite Francaise.

20. Ursula LeGuin, The Left Hand of Darkness.

Comments: No, I didn’t forget George Eliot, these are “my favorites,” not “the best.” Maybe Edith Wharton would have made #21? Or Byatt’s Possession? The other marginal picks mostly would have come from the Anglosphere. I learned my favorite Latin American writers are all male.

The death curve is going vertical

Via Eric Topol.

Via Eric Topol.

Saturday assorted links

1. Why did Wikipedia’s competitors fail?

2. Wallabies from Australia have gained a foothold in the U.K. and may be there for good.

3. Magnus Carlsen on Queen’s Gambit and other matters.

4. Supermarkets drop brand of coconut milk after allegations of forced monkey labor.

5. Best inventions of 2020? (not my picks)

Radio and riots

Although the 1960s race riots have gone down in history as America’s most violent and destructive ethnic civil disturbances, a single common factor able to explain their insurgence is yet to be found. Using a novel data set on the universe of radio stations airing black-appeal programming, the effect of media on riots is found to be sizable and statistically significant. A marginal increase in the signal reception from these stations is estimated to lead to a 7% and 15% rise in the mean levels of the likelihood and intensity of riots, respectively. Several mechanisms behind this result are considered, with the quantity, quality, and the length of exposure to radio programming all being decisive factors.

That is from a recent paper by Andrea Bernini, a job market candidate from Oxford University. We forget sometimes that arguably the internet is a more peace-inducing institution than was radio.