Month: February 2022

Progresa after 20 Years

Remember the Mexican cash transfer program, sometimes used to support education? Some new results are in, and the program is looking pretty good:

In 1997, the Mexican government designed the conditional cash transfer program Progresa, which became the

worldwide model of a new approach to social programs, simultaneously targeting human capital accumulation

and poverty reduction. A large literature has documented the short and medium-term impacts of the Mexican

program and its successors in other countries. Using Progresa’s experimental evaluation design originally rolled out in 1997-2000, and a tracking survey conducted 20 years later, this paper studies the differential long-termimpacts of exposure to Progresa. We focus on two cohorts of children: i) those that during the period of differential exposure were in-utero or in the first years of life, and ii) those who during the period of differential exposure were transitioning from primary to secondary school. Results for the early childhood cohort, 18–20-year-old at endline, shows that differential exposure to Progresa during the early years led to positive impacts on educational attainment and labor income expectations. This constitutes unique long-term evidence on the returns of an at-scale intervention on investments in human capital during the first 1000 days of life. Results for the school cohort – in their early 30s at endline – show that the short-term impacts of differential exposure to Progresa on schooling were sustained in the long-run and manifested themselves in larger labor incomes, more geographical mobility including through international migration, and later family formation.

Here is the full paper by M. Caridad Araujo and Karen Macours from Poverty Action Lab.

No one cared about Bryan’s spreadsheets

From Bryan:

The most painful part of writing The Case Against Education was calculating the return to education. I spent fifteen months working on the spreadsheets. I came up with the baseline case, did scores of “variations on a theme,” noticed a small mistake or blind alley, then started over. Several programmer friends advised me to learn a new programming language like Python to do everything automatically, but I’m 98% sure that would have taken even longer – and introduced numerous additional errors into the results. I did plenty of programming in my youth, and I know my limitations.

I took quality control very seriously. About half a dozen friends gave up whole days of their lives to sit next to me while I gave them a guided tour of the reasoning behind my number-crunching. Four years before the book’s publication, I publicly released the spreadsheets, and asked the world to “embarrass me now” by finding errors in my work. If memory serves, one EconLog reader did find a minor mistake. When the book finally came out, I published final versions of all the spreadsheets underlying the book’s return to education calculations. A one-to-one correspondence between what’s in the book and what I shared with the world. Full transparency.

Now guess what? Since the 2018 publication of The Case Against Education, precisely zero people have emailed me about those spreadsheets. The book enjoyed massive media attention. My results were ultra-contrarian: my preferred estimate of the Social Return to Education is negative for almost every demographic. I loudly used these results to call for massive cuts in education spending. Yet since the book’s publication, no one has bothered to challenge my math. Not publicly. Not privately. No one cared about my spreadsheets.

Here is more from Bryan Caplan. I would make a few points:

1. Work is hardly ever checked, unless a particular paper becomes politically focal in some kind of partisan dispute. You can take this as a sign that Bryan has not dented the political consensus so much, a point I think he would agree with.

2. Researchers discuss and consider your work in a particular area far, far more if you are an insider in that area, making the seminar circuit at top schools. To be clear, Bryan’s work is discussed far more by intelligent humans who are not education researchers, compared to what virtually all of the education researchers have produced. Bryan writes in internet space, where the barriers to entry are much lower. Good for him, I say (duh), but of course not everyone wishes to lower the entry barriers in this manner. And internet writing does have entry barriers of its own. For instance, Bryan has been blogging steadily for many years, which many researchers simply do not wish to do or maybe cannot do well at all.

3. Overall I think we are entering a world where “research” and “idea production” are increasingly separate endeavors. And the latter is moving to the internet, even when it is supplemented by non-internet crystallizations such as books. Bryan’s ideas, of course, have been germinating on EconLog for some time before his education book came out. Do you like this new world? What are its promises and dangers?

Running economies hot lowers real wages

It doesn’t raise them, as you might have been taught on Twitter over the last 10-15 years. Here is the report from the UK:

British households are facing the biggest fall in real incomes in 30 years as inflation gallops ahead of wage growth, a stark illustration of the challenge facing central banks as they try to tame prices without snuffing out recoveries from the pandemic.

The Bank of England forecasts that average incomes in Britain after accounting for wage growth, inflation, tax increases and benefit changes will fall by 2% this year—the steepest decline since comparable records began in 1990. The pinch is expected to hold back the broader economy just when it needs all engines firing to propel itself clear of the slump caused by the pandemic.

Here is more from the WSJ.

What should I ask Thomas Piketty?

I will be doing a Conversation with him. So what should I ask?

Do note he has a new book coming out A Brief History of Equality.

Tuesday assorted links

1. Bob Solow making fun of Kydland and Prescott, via Dr. Ruth.

3. Craig Palsson, economics, and going viral on YouTube and TikTok.

4. AI and machine learning in economics.

5. Was the “Russian flu” in the late 19th century a rogue coronavirus? (NYT)

6. Twitter AMA with Marc Andreessen.

7. New Cecil Taylor jazz (NYT).

Heavy Wears the Crown and the Kohinoor

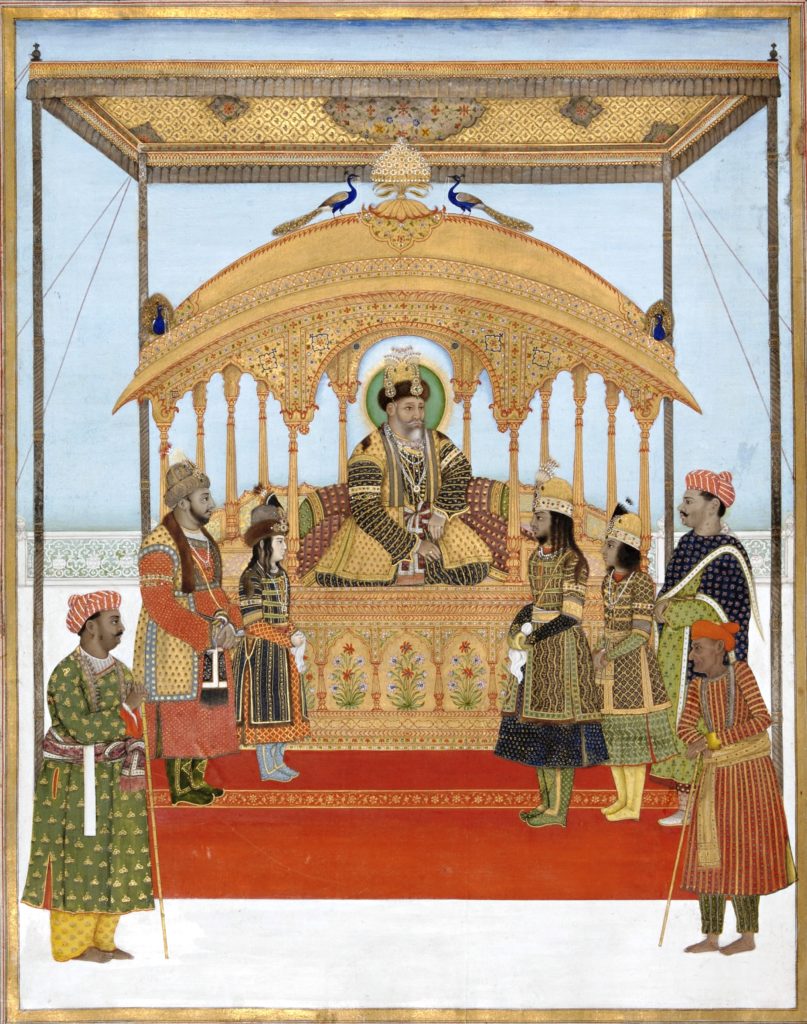

Shah Jahan is best known as the Mughal ruler who built the Taj Mahal. He spent much more of India’s wealth, however, building the Peacock throne (completed 1635), meant to rival the throne of Solomon. The value of the throne, perhaps the most bejeweled object ever created, can perhaps be understood by knowing that crowning one of the peacocks was the Kohinoor, one of the world’s largest diamonds. At the time, however, the Kohinoor wasn’t even considered the most impressive or valuable jewel in the throne!

Delhi was sacked by the Persian brigand Nader Shah in 1739. With ‘700 elephants, 4,000 camel and 12,000 horses’ Shah carted off hundreds of years of accumulated gold, silver and previous stones including the Peacock throne.

Nader brought the throne back to Persia but he soon went mad becoming ever more paranoid and vicious. He ordered his own son blinded and the eyes brought to him on a platter. Fearing a similar fate, some of his Afghan bodyguards turned on him and beheaded him. But one of his generals, Ahmad Khan Abdali, remained loyal, and amidst the violence and looting stood guard over the royal harem. He was rewarded by the first lady of the harem with the Kohinoor diamond and escaped to Afghanistan.

The rest of the Peacock throne was disbanded and disbursed to the winds although two of the other celebrated stones from the throne can be tracked through history. The Darya-i-Noor stayed in Persia were it eventually became part of the crown jewels of Mohammad Reza Shah, which as a child accompanied by my father I saw in Iran shortly before the revolution. The “Great Mughal” diamond eventually showed up in Amsterdam where it was bought by Count Orlov, the once-lover of Catherine the Great. Hoping to get back into her bed, he gifted her with the diamond but ended up only in debt and confined to a mental asylum. The Great Mughal is now on show in the Kremlin.

On his way back to Afghanistan, Ahmad Khan Abdali, who had escaped from the chaos of Nader Shah’s beheading, ran across a treasure caravan intended for Nader Shah. Commandeering the caravan he used its wealth to become the founder of the Durrani empire and the modern state of Afghanistan. Alas Ahmad Khan lost his nose to leprosy but kept the diamond until it fell to his heir, Timur Shah and then to his eventual heir (after much internecine warfare) Shah Zaman. Zaman was himself blinded with a hot needle “The point quickly spilled the wine of his sight from the cup of his eyes.” as Afghan historian Mirza ‘Ata put it poetically.

As the Durrani empire fell, the Sikh empire rose and the Kohinoor moved to Lahore under Ranjit Singh. The Sikhs, however, lost the Punjab to the East India Company who signed a peace deal with the boy king, Duleep Singh, which included the Kohinoor as tribute. Duleep would later be exiled to England where he would personally hand the Kohinoor over to his patron Queen Victoria.

After Queen Victoria’s death the Kohinoor was incorporated into various of the British crown jewels, excepting one period during World War II when it was hidden in a pond. As of last week, Queen Elizabeth announced that when Charles becomes King the Kohinoor will become part of the crown jewels of Queen Consort Camilla.

Addendum: Largely cribbed from the excellent Kohinoor by William Dalrymple and Anita Anand.

What are the costs of the megadrought in the Southwest?

Here are the basics:

Previous work by some of the same authors of the new study had identified the period of 2000 through 2018 as the second-worst megadrought since the year 800 — exceeded only by an especially severe and prolonged drought in the 1500s. But with the past three scorching years added to the picture, the Southwest’s megadrought stands out in the record as the “worst” or driest in more than a millennium.

Here is the WaPo story. I now have three questions, none meant sarcastically, I really want to know:

1. How much has gdp in these regions been damaged over this time period?

2. How much have real estate prices been danaged?

3. How much has migration into these states declined, relative to what would have been the baseline?

Now this is by no means the only set of costs from global warming and climate change. But if we are just trying to calculate the costs of climate change on the Southwest, and other dry but rich areas, which inferences should we draw? You might think “the real problems haven’t come yet,” and maybe so, but shouldn’t that show up in the asset prices and migration patterns?

A blow to Canadian rule of law

Canada’s prime minister Justin Trudeau has invoked emergency powers in an attempt to quell protests against mandatory Covid-19 vaccinations that continue to grip the nation’s capital, drawing the ire of some provincial leaders.

Trudeau pledged at a press conference on Monday that use of the powers under the Emergencies Act — which gives the federal government broad authority, including the ability to prohibit public assembly and travel — “will be time-limited, geographically targeted, as well as reasonable and proportionate to the threats they are meant to address”. He also said the military would not be called in to deal with blockades.

Chrystia Freeland, finance minister, said Canadian banks and other financial service providers will be able to immediately freeze or suspend accounts without a court order if they are being used to fund blockades. She also warned companies that authorities will freeze their corporate accounts and suspend insurance if their trucks are being used in the protests.

Here is more from the FT. Should not the Canadian police be able to solve this issue on their own?

Monday assorted links

TechCrunch interviews me about crypto

TC is the interviewer, TechCrunch (John Biggs), not I, here is one bit:

TC: Folks liken this tech to cargo cults. You build the trappings of an economic system in hopes that one magically appears. Is this accurate?

Cowen: I think the crypto people are super, super smart on average. They’re smarter than economists on average. And they have skin in the game, right?

TC: Does the profit motive color the experience?

Cowen: Well, people in crypto want to build systems that work. It’s fair for all of us to have uncertainty about how that will go. But the price of crypto assets have been pretty high for a while now and they’ve taken big hits and come back. So I don’t think you can now say it’s just a bubble. So what exactly it would be is still up for grabs, but I think the bubble view is increasingly hard to maintain.

TC: Are we assuming this stuff is here to stay? That bitcoin won’t disappear in a decade?

Cowen: That is strongly my belief. Now, there’s a lot of other cryptoassets and I think most of those will disappear. There were many social media companies fifteen years ago also and many are not around but obviously social media is very much a thing.

TC: What’s your take on decentralized, from an economic perspective?

Cowen: I think we will end up with both centralized crypto and decentralized crypto, and they will serve quite different functions. So, obviously, there were advantages to centralized systems. You can change the more quickly, more readily. There’s someone to manage them, someone to oversee them. But you also pile up costs. So I think both will prove robust. But again, I would readily admit that still up for grabs.

There is much more at the link.

Bram Stoker, Dracula, and Progress Studies

The Dracula novel is of course very famous, but it is less well known that it was, among other things, a salvo in the direction of what we now call Progress Studies. Here are a few points of relevance for understanding Bram Stoker and his writings and views:

1. Stoker was Anglo-Irish and favored the late 19th century industrialization of Belfast as a model for Ireland more generally. He also was enamored with the course of progress in the United States, and he wrote a pamphlet about his visit.

2. From Wikipedia:

He was a strong supporter of the Liberal Party and took a keen interest in Irish affairs. As a “philosophical home ruler”, he supported Home Rule for Ireland brought about by peaceful means. He remained an ardent monarchist who believed that Ireland should remain within the British Empire, an entity that he saw as a force for good. He was an admirer of Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone, whom he knew personally, and supported his plans for Ireland.Stoker believed in progress and took a keen interest in science and science-based medicine.

3. The novel Dracula contrasts the backward world of Transylvania with the advanced world of London, and it shows the vampire cannot survive in the latter. The Count is beaten back by Dr. Van Helsing, who uses science to defeat him and who serves as a stand-in for Stoker and is the de facto hero of the story.

4. One core message of the novel is “Ireland had better develop economically, otherwise we will end up like a bunch of feudal peasants, holding up crosses to fend off evil, rapacious landowners.” At the time, the prominent uses of crosses was associated with Irish Catholicism. And is there a more Irish villain than the absentee landlord, namely Dracula? Dracula is also the kind of warrior nobleman who, coming from England, took over Ireland.

5. In the novel, science and commerce have the potential to defeat underdevelopment. Stoker’s portrait of Transylvania, most prominent in the opening sections of the novel, also suggests that “underdevelopment is a state of mind.” And it is correlated with feuding sects and clans, again a reference to the Ireland of his time, at least as he understood Catholic Ireland. Here is more on Stoker’s views on economic development and modernization for both Ireland and the Balkans.

6. Stoker was obsessed with “rationalizing” (in the Weberian sense) the employment relation and also the bureaucracy His first non-fiction work was “The Duties of Clerks of Petty Sessions.” Progress was more generally a recurring theme in his non-fiction writings, for instance “The Necessity of Political Honesty.” He called for an Ireland of commerce, education, and without “warring feuds.”

7. For Stoker, sexual repression is needed to further societal progress and economic development, and in this regard Stoker anticipates Freud. Dracula abides by most laws and norms, except the sexual/cannibalistic ones. Dracula and Lucy, who give in to their individual desires, end up as the big losers. For the others, societal order is restored, and the lurid sexuality that pervades the book is dampened by the restoration of order.

8. Christ and Dracula are mirror opposites (the stake, the cross, resurrection at dawn rather than sunset, the role of blood drinking reversed, the preaching of immortality in opposite ways, the inversion of who sacrifices for whom, and more). A proper societal outcome is obtained when these two opposites end up neutralizing each other. Stoker’s vision of progress is fundamentally secular. (See Clyde Leatherdale on all this.)

9. From Hollis Robbins: “Britain’s economic prosperity in the nineteenth century was largely dependent on the adoption of international standards such as Greenwich Mean Time and the universal day, which ensured smooth coordination for trade, legal transactions, railroad travel, and mail delivery. Dracula, whose powers are governed by the sun and the moon rather than clocks and calendars, works to destabilize social coordination. His objective is not only literally to “fatten on the blood of the living,”6 but also more broadly to suck the lifeblood of a thriving commercial economy at the dawn of a global age. Under Dracula’s spell, humans forget the time, becoming listless, unproductive, and indifferent to social convention. At heart, the fundamental battle in Stoker’s Dracula is a death struggle between standard time as an institutional basis for world markets and planetary time governing a primitive, superstitious existence.”

10. In an interview Stoker once said: “I suppose that every book of the kind must contain some lesson, but I prefer that readers should find it out for themselves.” There are numerous ways to take that remark, not just what I am suggesting.

Sunday assorted links

1. Is the gene-sequencing company Illumina a monopoly? (NYT)

2. “In short: the more one’s intellectual contributions are defined by strengths, where those strengths also essentially depend on a broad base, the more your regional background is likely to shape your intellectual contributions.” More Nate Meyvis. And Nate on the value of T-shaped reading plans.

4. People on Twitter are using more political identifiers than before. And more yet if you count pronouns.

How to negotiate your assistant professor salary

Jennifer Doleac writes:

I’ve discovered a new passion for helping junior women in econ negotiate better job offers. It’s easier to see what you deserve from the outside (always: more than they are offering…)

Great! Here are a few tips from me, not just for women, noting that I am going to skip over the super-important “make sure you are in high demand” kind of advice. I am assuming you already have an offer in hand, and wish to make the most of it.

1. Make sure they have made you the full offer before responding in any way, other than with polite enthusiasm. That means salary, teaching load, moving expenses, faculty housing options, length of contract, research and travel fund, and anything else you might care about, such as a joint appointment. Don’t respond to any one bit of it until you have drawn out all the blood from the source.

2. You don’t have anything until it is in writing. Duh.

3. It is fine to ask the departmental chair what else you might ask for. In such matters the chair is usually (but not always) on your side. In any case, this is not a faux pas.

4. Very often the components of your offer come from distinct pools of money or resources, controlled by different agents. You want to “tap” on each and every part of the offer, to see if it might be flexible. Inflexibility on one part of the offer does not have to mean inflexibility on all the other parts. Different pots of money! So ask for more along all margins, but do so politely. Rudeness doesn’t help with these kinds of bureaucracies.

5. In most situations you can get a small amount extra by bargaining over the salary, and indeed you should. But you cannot get much more unless you have a written offer in hand from another place for a higher salary. Recognize your limitations. And a higher salary offer from a non-academic source often means zero in this bargaining game. You can’t expect anything close to a match. At best it will be an excuse for them to bump you up a few more thousand dollars.

6. It is fine to ask for a semi-formal commitment on what you might teach, but do not expect this to be put in writing. Odds are it will be honored, but not 100% for sure. “I would like to teach in your honors sequence” is a perfectly legitimate ask, if appropriate to the situation.

7. Always ask for a course off for your first year, at the very least. And learn what will be the future rate for buying out of courses.

8. Most generally, while you should always be polite, “them liking you” is not an outcome you are looking to achieve at this stage of the game. They can like you plenty later. Probably you should feel just a little uneasy that perhaps you are asking for too much.

9. As for women in particular, there is a literature suggesting that possibly women do not bargain hard enough in the workplace. Whatever stance you take on this broader question, if you are a women at least ask — and check with some mentors — as to whether you are making this mistake. Actually men should do this too.

10. You do have a limited ability to ask for an extension on your offer and when you must say yes or no. But do not think you can stretch this too far, and it is often not in the interests of the school, or for that matter the department and chair, to give you much leeway here. Basically you want to do this to drum up a better offer from elsewhere, and they know this.

What else? Here is my earlier post on exploding offers.

The Room

Has to be seen not to be believed.

Hat tip: Kottke via Joel Selanikio.

The Puzzle of Falling US Birth Rates since the Great Recession

That is a new JEP piece by Melissa S. Kearney, Phillip B. Levine, and Luke Pardue. The piece, while not easily summarized, is interesting throughout. Here is one bit:

The decline in birth rates has been widespread across the country. Birth rates fell in every state over this period, except for North Dakota. One possible explanation for the increase in North Dakota birth rates is the fracking boom that occurred in this state over those years, which has been shown in other research to increase the birth rate (Kearney and Wilson 2018). But as can be readily seen in the map, there is substantial variation in the extent of the decline across places.

Births fell the most in the South, in the West, and in the Southwestern and Mountain states. However, the set of states that experienced larger declines is varied, also including some Midwestern and New England states, notably Connecticut, Illinois, and Massachusetts. Births fell the most in the Southwestern and Western states. The sizable Hispanic population in much of this region is consistent with the particularly large decline in births among Hispanic women, driven by a decline in births among both native and foreign-born Mexicans. The fact that other states with smaller shares of Hispanic residents (like Georgia and Oregon) also experienced large declines, though, further clarifies the broad-based nature of the decline.

And this:

The percentage of sexually active women who report using long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) increased from 5.5 percent in 2004 to 10.7 in 2017 and could have contributed to declining birth rates. The simple correlation, though, between the percentage point change in LARC usage in a state and the change in birth rates is wrong-signed (that is, positive), albeit close to zero. This suggests that take-up of LARCs has likely not played an important role in explaining the decline in the aggregate birth rate over this period.

Overall it is interesting how many factors do not seem to matter much.