Month: December 2022

Canine Coaseanism

We are for a while caretakers for a dog, and so I have started thinking what kind of trades I might make with the beast. Of course for Darwinian reasons dogs have co-evolved with humans to be fairly cooperative, at least for some breeds (and this is a very smart, easily trained breed, namely an Australian shepherd). So the dog’s behavior (my behavior?) already mirrors some built-in trades, such as affection for food. But what kinds of additional trades might one seek at the margin?

One thought comes to mind. I would like to signal to the canine that, when I get up from the sofa, he does not need to follow me because there is no chance I will offer him a food treat. It would be better if he would just stay sleeping. And yet this equilibrium is impossible to achieve. Nor does rising from the sofa quietly succeed in fooling him, he follows me nonetheless.

Overall, though, I conclude that the current (spayed) version of the dog is already fairly Coasean in his basic programming.

One look at our future

The following comes from a deleted tweet, so I have paraphrased in some places and also removed references to a few specific individuals. If the author wishes to reclaim ownership of these ideas, I will write a separate blog post crediting him:

1. AGI and Fusion are what matter. Fusion accelerates AGI, since AGI is just exaflops spent on training.

2. GPT 3.5 (ChatGPT) is civilization-altering. GPT-4, which is 10x better, will be launched in the second quarter of next year.

3. Google is worried, but Microsoft is all-in, and is building many more data centers to lead the charge. Bing search is getting GPT integration next year.

4. Model configuration and training parameters don’t matter. Intelligence is just GPU exaflops spent on training.

5. If #4 is true, civilization becomes a decentralized crypto network, where computers are contributed for training and earning tokens. Querying the model costs tokens.

6. One last centralizing force — gradient descent is synchronous. Needs high GPU coordination and fast network bandwidth. Current trend is civilization centralizing with Microsoft laying 10x bigger Open AI data centers.

7. Gradient descent is the process of error correction, where an N-layer model predicts an output. When that’s far away from the target, we correct all the layer weights slightly to re-aim.

8. Some other batch of stuff I didn’t understand and cannot paraphrase.

9. A lot of the configurations work equally fine. If you throw the same GPU exaflops at the model — they perform more or less the same. Probably that is why it is evolutionarily easy to invent the brain. Open AI is at 10 exaflops right now vs. 1000 for the human brain. Probably going to equalize in five years.

10. Models are so good already that only expert training matters anymore. Co-pilot for X is in play. Anyone building a Co-pilot for my browser? Browsers are largely text-based, which GPT fully understands.

There you go! Speculative, of course.

Wednesday assorted links

Ohio teen fact of the day

The number of 11th and 12th grade males experiencing gambling problems, such as lying about how much they lost, or being unable to control their gambling, rose to 8.3% in 2022 from 4.2% in 2018, according to one survey of 7,500 7th through 12th graders in Wood County, Ohio.

People who research and treat problem gambling say the line between gambling and videogaming is blurring. Videogames, which are often played on smartphones as well as computers and game consoles, include features that mimic gambling activities like roulette and slot machines.

The FDA’s Lab-Test Power Grab

The FDA is trying to gain authority over laboratory developed tests (LDTs). It’s a bad idea. Writing in the WSJ, Brian Harrison, who served as chief of staff at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019-2021 and Bob Charrow, who served as HHS general counsel, 2018-2021, write:

We both were involved in preparing the federal Covid-19 public-health emergency declaration. When it was signed on Jan. 31, 2020, the intent was to cut red tape and maximize regulatory flexibility to allow a nimble response to an emerging pandemic.

Unknown to us, the next day the FDA went in the opposite direction: It issued a new requirement that labs stop testing for Covid-19 and first apply for FDA authorization. At that time, LDTs were the only Covid tests the U.S. had, and many were available and ready to be used in labs around the country. But since the process for emergency-use authorization was extremely burdensome and slow—and because, as we and others in department leadership learned, it couldn’t process applications quickly—many labs stopped trying to win authorization, and some pleaded for regulatory relief so they could test.

Through this new requirement the FDA effectively outlawed all Covid-19 testing for the first month of the pandemic when detection was most critical. One test got through—the one developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—but it proved to be one of the highest-profile testing failures in history because the entire nation was relying on the test to work as designed, and it didn’t.

When we became aware of the FDA’s action, one of us (Mr. Harrison) demanded an immediate review of the agency’s legal authority to regulate these tests, and the other (Mr. Charrow) conducted the review. Based on the assessment, a determination was made by department leadership that the FDA shouldn’t be regulating LDTs.

Congress has never expressly given the FDA authority to regulate the tests. Further, in 1992 the secretary of health and human services issued a regulation stating that these tests fell under the jurisdiction of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, not the FDA. Bureaucrats at the FDA have tried to ignore this rule even though the Supreme Court in Berkovitz v. U.S. (1988) specifically admonished the agency for ignoring federal regulations.

Loyal readers will recall that I covered this issue earlier in Clement and Tribe Predicted the FDA Catastrophe. Clement, the former US Solicitor General under George W. Bush and Tribe, a leading liberal constitutional lawyer, rejected the FDA claims of regulatory authority over laboratory developed tests on historical, statutory, and legal grounds but they also argued that letting the FDA regulate laboratory tests was a dangerous idea. In a remarkably prescient passage, Clement and Tribe (2015, p. 18) warned:

The FDA approval process is protracted and not designed for the rapid clearance of tests. Many clinical laboratories track world trends regarding infectious diseases ranging from SARS to H1N1 and Avian Influenza. In these fast-moving, life-or-death situations, awaiting the development of manufactured test kits and the completion of FDA’s clearance procedures could entail potentially catastrophic delays, with disastrous consequences for patient care.

Clement and Tribe nailed it. Catastrophic delays, with disastrous consequences for patient care is exactly what happened. Thus, Harrison and Charrow are correct, giving the FDA power over laboratory derived tests has had and will have significant costs.

Best movies of 2022

The Lost Daughter, TV but still good, a movie of sorts, based on Ferrante.

Belle, spectacular Japanese anime.

Licorice Pizza, a good normal movie, captured California well.

Compartment Number Six, with a new meaning after the war of course.

Petit Maman, French, short, plays mind games with you, profound.

The Quiet Girl (Irish)

Vesper, Lithuanian, dreamy, Tarkovsky influence but faster-paced, an underrated movie this year.

Tár, really quite good and interesting.

Decision to Leave, Korean crime drama with Hitchcockian twists and inspirations.

The Fabelmans, Ignore the cloying preview.

Saint Omer, French-Senegalese courtroom drama.

Clytaemnestra, Korean movie, one hour long.

EO, Polish movie about a donkey, better than you think.

Overall an abysmal year for Hollywood, a pretty good year for the movies. I haven’t yet seen Oppenheimer or Bardo, so their absence on the list should not be taken as a negative signal.

Why are Americans spending less on holiday gifts?

That is the question behind my latest Bloomberg column:

The research is clear: Americans are becoming less generous over the holidays. Not to sound too much like a Scrooge, but this is not necessarily a bad thing.

In 1999, Americans said they planned to spend $1,300 (converting to 2020 dollars) on holiday gift giving. In 2020, that amount was about $800. These numbers are based on Gallup data, but retail sales figures show a broadly similar pattern. From 1935 through 2000, gift-giving tended to rise with disposable income. Since 2000, gift-giving has fallen as national disposable income has risen.

…One hypothesis is that Americans are simply getting less generous. Yet charitable giving is robust, so that’s probably not right.

An alternative possibility is that Americans are too rich for gifts to make sense. It’s not only that billionaires are hard to buy for; the rest of us are, too. You might think your friends already have most of the important things they need, so how can you buy them something meaningful at the margin? This logic doesn’t hold for all Americans, but perhaps the higher earners account for a big enough share of the gift-giving total that it exerts a downward pull on the numbers.

The cheeriest scenario — again, speaking strictly as an economist — is that Americans are realizing that gift-giving often doesn’t make much sense. If you give me a gift and I give you a gift, neither of us is quite sure what the other wants. We might both be better off if we each spent the money on ourselves. Under this hypothesis, Americans are not becoming less generous, they are becoming more rational.

Another rationale for gift-giving is that it tightens familial and social bonds. Perhaps it does, but it is not the only means for doing so. More and better communication — which has also become cheaper and easier over the last two decades, with email, texts and cheaper phone calls — may make gift-giving seem less essential.

There is also the possibility that we, as a society, have lost that “Christmas spirit,” whatever that might mean. After all, secularization is rising and churchgoing is declining. Christianity is less central to American life. Whether this social development is all good or bad will of course depend on your point of view.

What do you all think are the likely causes here?

*Paved Paradise: How Parking Explains the World*

Henry Grabar has written an excellent book on how badly America has screwed up its parking policies, and in turn ruined many of its cities, or at least parts of them.

Here is just one little tidbit:

Parking on the curb was not such a great option in those days: in 1990, 147,000 cars were stolen in New York City — one theft for every fifty residents. My parents joined the club shortly before Christmas, 1993. Their next car went into a garage, a prewar building with a cable-hauled elevator serving three floors of parking…

The revival of Manhattan around the millennium, which often took the form of apartments replacing parking, and the concurrent decline of car thefts, which fell by an astounding 96 percent between 1990 and 2013, put a lot of pressure on the curb.

I wish such books would spend more time discussing whether dense urban areas are simply a fertility trap. Nonetheless excellent work, and everyone interested in urban economics (or parking) should pick this one up. Due out in May, you can pre-order here.

Tuesday assorted links

1. Have Irish IQs not seen such a radical Flynn effect in the last few decades?

2. Phyllis Wheatley.

3. The metaphysics of LLM, and yes Wittgenstein has been underrated.

4. Context is that which is becoming increasingly scarce?

5. Dwarkesh Patel podcast with Aella (note the language and some of the content is not safe for work).

Health Care Spending Growth Has Slowed: Will the Bend in the Curve Continue?

In large part yes:

Over 2009-2019 the seemingly inexorable rise in health care’s share of GDP markedly slowed, both in the US and elsewhere. To address whether this slowdown represents a reduced steadystate growth rate or just a temporary pause we specify and estimate a decomposition of health care spending growth. The post-2009 slowdown was importantly influenced by four factors. Population aging increased health care’s share of GDP, but three other factors more than offset the effect of aging: a temporary income effect stemming from the Great Recession; slowing relative medical price inflation; and a possibly longer lasting slowdown in the nature of technological change to increase the rate of cost-saving innovation. Looking forward, the

post-2009 moderation in the role of technological change as a driver of growth, if sustained, implies a reduction of 0.8 percentage points in health care spending growth; a sizeable decline in the context of the 2.0 percentage point differential in growth between health care spending and GDP in the 1970 to 2019 period.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Sheila D. Smith, Joseph P. Newhouse, and Gigi A. Cuckler.

What I’ve been reading

Ahmet T. Kuru, Islam, Authoritarianism, and Underdevelopment: A Global and Historical Comparison is one of the best books on why Islam fell behind Western Europe. I don’t think it solves the puzzle, but has plenty of good arguments in the “rent-seeking” direction.

Newly published is Daniel B. Klein, Smithian Morals, Amazon link here, some of the essays are with co-authors. Free, open access version is here.

Nicolai J. Foss and Peter G. Klein, Why Managers Matter: The Perils of the Bossless Company, is an interesting defense of corporate hierarchy, based on economic reasoning and also a dash of Hayek.

Jamieson Webster, Disorganisation & Sex. Lacanian, yet readable. Recommend to those who think they might care, but it will not convince the unconverted.

There is the interesting Plato Goes to China: The Greek Classics and Chinese Nationalism, by Shadi Bartsch. Here is my very good CWT with her, in which we discuss the topics of the book a bit.

Pretty good is Jon K. Lauck, The Good Country: A History of the American Midwest, 1800-1900.

There is Owen Ullmann, Empathy Economics: Janet Yellen’s Remarkable Rise to Power and Her Drive to Spread Prosperity to All.

And a new libertarian memoir, Murray Sabrin, From Immigrant to Public Intellectual: An American Story.

Dalibor Rohac, Governing the EU in an Age of Division is a classical liberal take on its topic.

Monday assorted links

Addendum to best books of 2022

First, there are two books I haven’t read yet — new translations — but they are almost certainly excellent and deserving of mention. They are:

Ovid, Metamorphoses, translated by Stephanie McCarter.

Alessandro Manzoni, The Betrothed, translated by Michael F. Moore.

From fiction I would add to my earlier list:

R.F. Kuang, Babel: An Arcane History,

and Olivier Guez, The Disappearance of Josef Mengele, excellent and easy to read in one sitting.

In non-fiction I would give especially high ratings to the following additions:

Andrew Mellor, The Northern Silence: Journeys in Nordic Music & Culture. I will read this one again. It assumes some knowledge of the Nordic countries and also some knowledge of classical music, but it is exactly the kind of book I hope people will write. It explains at a conceptual level how those countries built up such effective networks of musical production and consumption.

Keiron Pim, Endless Flight: The Life of Joseph Roth. Gripping throughout.

Rodric Braithwaite, Russia: Myths and Realities. Perhaps a little simple for some readers, but probably the best place to start on the topic of Russian history.

Allan Kozinn and Adrian Sinclair. The McCartney Legacy: Volume 1: 1969-1973. Having now finished the work, I can’t think of any biography that better integrates the tale of the life and the tale of the creative work. And it changed my views on Paul a good deal, for instance he wrote many of his best solo songs earlier than I had thought.

Here is my earlier non-fiction list for 2022.

The Birx Plan for Early Vaccination of the Nursing Homes

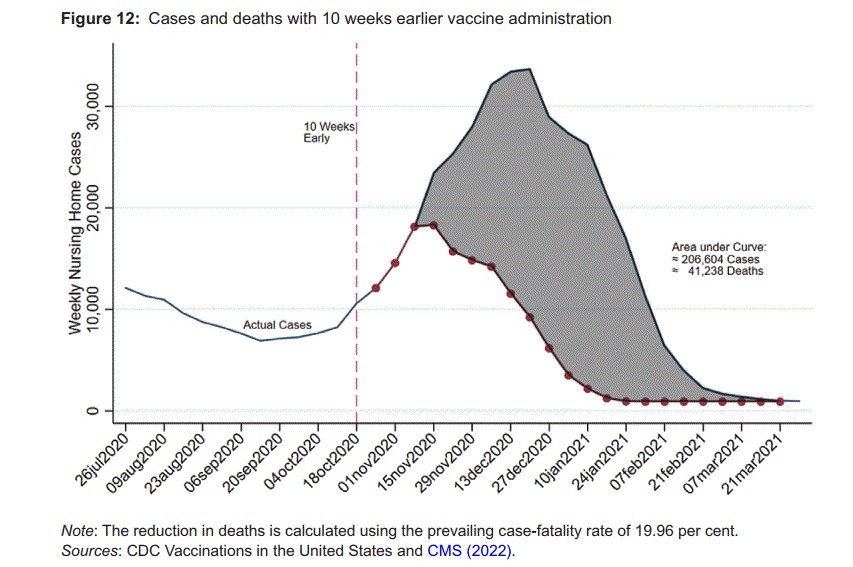

In Covid in the nursing homes: the US experience, Markus Bjoerkheim and I show that the Great Barrington “focused protection” plan was unlikely to have worked. I covered this last week. But there was one strategy which could have saved tens of thousands of lives–early vaccination. If the vaccine trials had been completed just 5 weeks earlier, for example, we could have saved 14 thousand lives in the nursing homes alone. But put aside the possibility of completing the trials earlier. There was another realistic possibility under our noses. We had could have offered nursing home residents the vaccine on a compassionate use basis, i.e. even before all the clinical trials were completed. An early vaccination option was neither unprecedented nor a question of 20-20 hindsight, early vaccination was discussed at the time:

Deborah Birx, the coordinator of the White House Coronavirus Task Force, forcefully advocated that nursing home residents should be given the option of being vaccinated earlier under a compassionate use authorization (Borrell, 2022). Many other treatments, such as convalescent plasma, were authorized under compassionate use procedures and there was more than enough vaccine available to vaccinate all nursing home residents. As a first approximation we find the Birx plan would have prevented in the order of 200,000 nursing home cases and 40,000 nursing home deaths. To put that in perspective, it amounts to reducing overall nursing home Covid deaths by over 26 per cent (using all CMS reported resident nursing home deaths as of 5 December 2021, and estimates of underreported deaths from Shen et al. (2021)).

The lesson is not primarily about the past. It’s about the central importance of vaccines in any plan to protect the vulnerable and about how we should be bolder and braver the next time.

Addendum: See also Tyler’s tremendous post (further below) on focused protection.

Who was really for “focused protection of the vulnerable”?

Yes I do mean during the Covid-19 epidemic. As a follow-up post to Alex’s, and his follow-up, here are some of the effective measures in protecting the vulnerable, or they would have been more effective, had we done them better:

1. Vaccines, including speedy approval of same.

2. Prepping hospitals in January, once it became clear we should be doing so. That also would have limited lockdowns! And yet we did basically nothing.

3. Speeding up and improving the research process for anti-Covid remedies and protections.

4. First Doses First, when that policy was appropriate, among other policy ideas (NYT).

5. Effective and rapid testing equipment, readily available on the market.

If you were out promoting those ideas, you were acting in favor of protecting the vulnerable. If you were not out promoting those ideas, but instead talked about “protecting the vulnerable” in a highly abstract manner, you were not doing much to protect the vulnerable.

And here are three actions that endangered the vulnerable rather than protecting them:

5. Publishing papers suggesting a very, very low Covid-19 mortality rate, and then sticking with those results in media appearances after said results appeared extremely unlikely to be true.

6. Maintaining vague (or in some cases not so vague) affiliations with anti-vax groups.

7. Not having thought through how “herd immunity” doctrines might be modified by ongoing mutations.

Keep all that in mind the next time you hear the phrase “protecting the vulnerable.”