Month: November 2024

Jay Bhattacharya at the NIH

Trump has announced the appointment, so it is worth thinking through a few matters. While much of the chatter is about the Great Barrington Declaration, I would note that Bhattacharya has a history of focusing on the costs of obesity. So perhaps we can expect more research funding for better weight loss drugs, in addition to other relevant public health measures.

Bhattacharya also has researched the NIH itself (with Packalen), and here is one bit from that paper: “NIH’s propensity to fund projects that build on the most recent advances has declined over the last several decades. Thus, in this regard NIH funding has become more conservative despite initiatives to increase funding for innovative projects.”

I would expect it is a priority of his to switch more NIH funding into riskier bets, and that is all to the good. More broadly, his appointment can be seen as a slap in the face of the Fauci smug, satisfied, “do what I tell you” approach. That will delight many, myself included, but still the question remains of how to turn that into concrete advances in public health policy. Putting aside the possibility of another major pandemic coming around, that is not so easy to do.

My main worry is simply that NIH staff will not trust their new director. The problem is not so much GBD, which can be compartmentalized as a “political” stance, but rather the earlier claims that many more people had Covid early than we had thought, and that expected fatalities were going to be quite low, with a maximum of 40,000. We all make mistakes, the question is how those mistakes get processed. If you interrogate Perplexity it will report “Bhattacharya has not publicly acknowledged or confessed to these mistakes in his early predictions.” You don’t have to agree with Perplexity (though contrary cites are welcome!), rather it suffices to say that reflects a common perception of the scientific community. He also seemed to be pushing those low fatality estimates for longer than might have been considered appropriate. And that is indeed a problem for his tenure at the NIH.

The danger is simply that NIH staff will double down on risk aversion, and they may not so readily support any attempt to make the grants themselves riskier, or rooted in the greater discretion of program directors, a’la DARPA and the like. They will fear that their director will not sufficiently follow the evidence, or admit when mistakes are being made and reverse course. Even if you fully agree with GBD and the like, I hope you are able to see this as a relevant problem. Every institutional revolution requires supportive troops on the inside, even if they are only a minority.

I very much hope this works out well, but in the meantime that is my reservation.

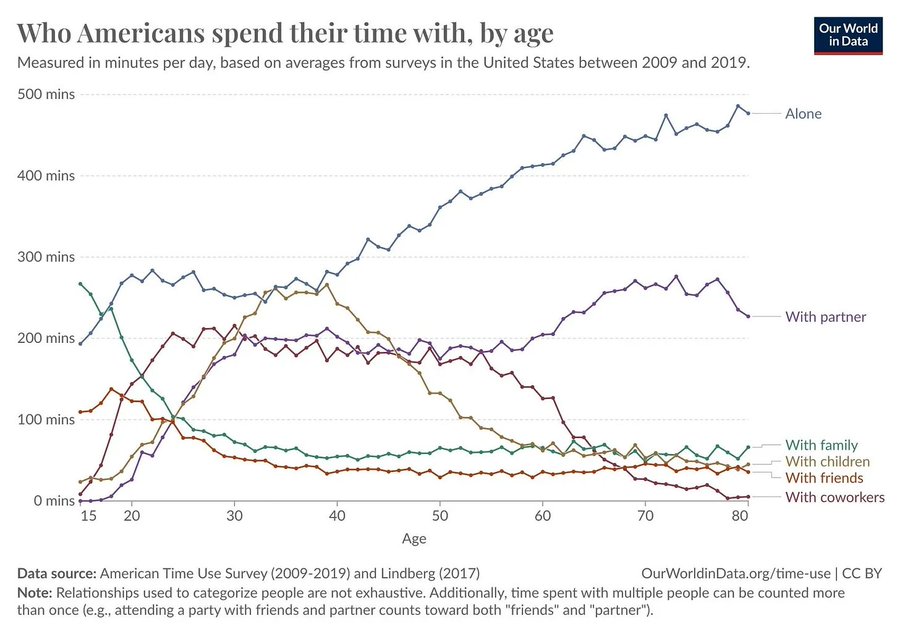

Who Americans spend their time with, by age

Via the excellent Bryan Caplan.

The Consequences of Limiting the Tax Deductibility of R&D

We study the tax payment and innovation consequences of limiting the tax deductibility of research and development (“R&D”) expenditures. Beginning in 2022, U.S. companies are required to capitalize and amortize R&D rather than immediately deduct these expenditures. We utilize variation in U.S. firms’ fiscal year ends to test the effects of the R&D tax change in a difference-indifferences framework. We first document that affected U.S. firms’ cash effective tax rates increase by 11.9 percentage points (62%), on average. We then test and find decreases in R&D investment among domestic-only, research-intensive, and constrained firms. In aggregate, these estimates translate to a reduction in R&D of $12.2 billion in the first year among the most research-intensive firms. Further, we observe decreased capital expenditures and share repurchases among affected companies, suggesting that firms also reduced other types of investment and shareholder payout to meet the increased cash tax liability. The paper provides policy-relevant evidence about the significant real effects of limiting innovation tax incentives.

That is from a new paper by Mary Cowx, Rebecca Lester, and Michelle L. Nessa. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Kevin Hassett to lead the NEC?

Bloomberg says so, a very good pick.

Can we expect large federal workforce cuts?

Wow, our government employees market is now projecting a new low of just 60k cuts For context, there are a record 23.4 million government employees When Elon Musk took over Twitter, he reduced the workforce by more than 80%

That is from Kalshi. Here is the market.

Tuesday assorted links

More Randian villains

Gavin Newsom, California’s Democratic governor, announced on Monday that he would reinstate a tax credit for electric vehicle purchases if the incoming Trump Administration removes federal EV tax credits. But the state may not extend the credits to Tesla because of the company’s large market share. Tesla’s stock price fell 4% on Monday.

Here is more from The Information (gated). GPT comments.

Birth Dearth and Local Population Decline

Local population decline has spread rapidly since 1970, with half of counties losing population between 2010 and 2020. The workhorse economic models point to net out-migration, likely driven by changing local economies and amenities, as the cause of this trend. However, we show that the share of counties with high net out-migration has not increased. Instead, falling fertility has caused migration rates that used to generate growth to instead result in decline. When we simulate county populations from 1970 to the present holding fertility at its initial level, only 10 percent of counties decline during the 2010s.

That is from a new paper by Brian Asquith and Evan Mast. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

My Conversation with Russ Roberts on Vasily Grossman’s *Life and Fate*

Here is the audio, video, and transcript. Russ and I agreed to read the book in its entirety and then discuss it. Here is part of the episode summary:

Russ and Tyler cover Grossman’s life and the historical context of Life and Fate, its themes of war, totalitarianism, freedom, and fate, the novel’s polyphonic structure and large cast of characters, the parallels between fascism and communism, the idea of “senseless kindness” as a counter to systemic evil, the symbolic importance of motherhood, the psychology of confession and loyalty under totalitarian systems, Grossman’s literary influences including Chekhov, Tolstoy, Dante, and Stendhal, individual resilience and moral compromises, the survival of the novel despite Soviet censorship, artificial intelligence and the dehumanization of systems, the portrayal of scientific discovery and its moral dilemmas, the ethical and emotional tensions in the novel, the anti-fanatical tone and universal humanism of the book, Grossman’s personal life and connections to its themes, and the novel’s enduring relevance and complexity.

Here is one bit from me:

COWEN: Amongst Soviet authors, he is the GOAT, one could say, to refer to our earlier episode. But this, to me, is one of the very few truly universal novels. The title itself, Life and Fate — it is about life and fate, but the novel is about so much more. It’s about war. It’s about slavery. It’s about love, motherhood, fatherhood, childbirth, rape, friendship, science, politics. How many novels, if any, can you think of that have all of those worlds in them in an interesting and insightful manner? Very few.

The one that comes closest to it is, in fact, his model. That’s Tolstoy’s War and Peace, a three-word title with an and in the middle and two important concepts. They’re both about war. They’re both about the invasions of Russia or the USSR. There’s a central family in both stories. The notion of what is fate or destiny is highly important to Tolstoy, as it is to Grossman, though they have different points of view.

Napoleon plays a significant role in War and Peace. In Life and Fate, Hitler and Stalin make actual appearances in the novel, which I find shocking when I read it, like, here they are on the page, and it’s actually somewhat plausible. So, he’s modeling this, I think, after War and Peace. He actually pulls it off, which is a miracle. I think it is a novel comparable in quality and scope and import to Tolstoy’s War and Peace, which is sometimes called the greatest novel ever. So that is a pretty amazing achievement.

And on some non-book issues:

COWEN: I think I should have said it’s a bimodal distribution, that you go one way or another. Look at it this way: In the simplest Bayesian model, your views should be a random walk, that the recent evolution of your views shouldn’t predict where you’ll end up tomorrow. But that’s not the case, really, with anyone that I’ve ever met. There’s some kind of trend in your views. You’re either getting more fanatical, getting more moderate, getting more religious, more or less something.

And that, to me, is one of the most interesting facts about human belief, is how hard it is to find belief as a random walk. So, what’s wrong with all of us? If you’re getting more moderate all the time, that’s wrong too. That’s a funny kind of, you could say, almost fanaticism, where you ought to say, “Well, I see the trend so I’m just going to leap to where I ought to be.” Then the next day, maybe 50 percent chance I’ll take a step back toward being more dogmatic or less moderate. But again, that’s not what we see from the moderates either.

ROBERTS: I wonder how much of it is the fact that it’s really convenient to have a system, gives you something to shove into the box. You’ve got this black box that you take the world’s events and you’ve decided how they should be processed. Then something new comes along, and you know how to deal with that because you’ve got this box; you’ve got all these great examples from the past.

At some point for me, I just started thinking that maybe the box doesn’t work all the time. I think a lot of people love the box. It’s a great source of comfort, whether it’s religion or ideology or other things. Maybe there’s just something peculiar about me. When you’re younger, certainty is deeply comforting because the world’s a bit too complicated to deal with. It still is, but I’m just less certain.

COWEN: There’s also a more charitable interpretation of what you’re describing. Think of yourself as working through problems, which is fine. Working through problems takes some time. You can’t every day pick up a new problem. The problems you’re working through as you — I wouldn’t say solve them, but as you somewhat make progress on them — that’s going to give you some persistence in the deltas of how your beliefs change.

I’m not sure — the pure Bayesian model might just be wrong. It’s so far from actual human practice. Maybe we shouldn’t just damn humans for not meeting it, but realize there are structures to how you work through things, and they are going to imply certain trends that go on for periods of time.

Recommended, obviously.

Monday assorted links

Regulating Sausages

In the comments on Sunstein on DOGE many people argued that regulations were mostly about safety. Well, maybe. It’s best to think about this in the context of a real example. Here is a tiny bit of the Federal Meat Inspection Act regulating sausage production:

In the preparation of sausage, one of the following methods may be used:

Method No. 1. The meat shall be ground or chopped into pieces not exceeding three fourths of an inch in diameter. A dry-curing mixture containing not less than 3 1⁄3 pounds of salt to each hundredweight of the unstuffed sausage shall be thoroughly mixed with the ground or chopped meat. After being stuffed, sausage having a diameter not exceeding 3 1⁄2 inches, measured at the time of stuffing, shall be held in a drying room not less than 20 days at a temperature not lower than 45 °F., except that in sausage of the variety known as pepperoni, if in casings not exceeding 1 3⁄8 inches in diameter measured at the time of stuffing, the period of drying may be reduced to 15 days. In no case, however, shall the sausage be released from the drying room in less than 25 days from the time the curing materials are added, except that sausage of the variety known as pepperoni, if in casings not exceeding the size specified, may be released at the expiration of 20 days from the time the curing materials are added. Sausage in casings exceeding 3 1⁄2 inches, but not exceeding 4 inches, in diameter at the time of stuffing, shall be held in a drying room not less than 35 days at a temperature not lower than 45 °F., and in no case shall the sausage be released from the drying room in less than 40 days from the time the curing materials are added to the meat.

The act goes on like this for many, many pages. All to regulate sausages. Sausage making, once an artisan’s craft, has become a compliance exercise that perhaps only corporations can realistically manage. One can certainly see that regulations of this extensiveness lock-in production methods. Woe be to the person who wants to produce a thinner, fatter or less salty sausage let alone who tries to pioneer a new method of sausage making even if it tastes better or is safer. Is such prescriptive regulation the only way to maintain the safety of our sausages? Could not tort law, insurance, and a few simple rules substitute at lower cost and without stifling innovation?

Prediction Markets Podcast

I was delighted to appear on the a16z crypto podcast (Apple, Spotify) talking with Scott Duke Kominers (Harvard) and Sonal Chokshi about prediction markets. It’s an excellent discussion. We talk about prediction markets, polling, and the recent election but also about prediction markets for replicating scientific research, futarchy, dump the CEO markets, AIs and prediction markets, the relationship of blockchains to prediction markets and going beyond prediction markets to other information aggregation mechanisms.

What should Jeff Holmes ask me?

Jeff is the producer of Conversations with Tyler, and soon he will be interviewing me, in part about the year’s CWT episodes (but not only). So what should he ask me?

Favorite fiction of 2024

Itamar Vieira Junior, Crooked Plow.

Karen Jennings, Crooked Seeds.

Richard Flanagan, Question Seven.

Guadalupe Nettel, La hija única, or Still Born

Sally Rooney, Intermezzo. Here is a good Henry Oliver review.

Of those I would pick Crooked Plow as the best. The new novels by Alan Hollinghurst and Murakami stand some chance of making the list. I will start them soon, and report back if I like them.

Alcohol estimates

The number of deaths caused by alcohol-related diseases more than doubled among Americans between 1999 and 2020, according to new research. Alcohol was involved in nearly 50,000 deaths among adults ages 25 to 85 in 2020, up from just under 20,000 in 1999.

The increases were in all age groups. The biggest spike was observed among adults ages 25 to 34, whose fatality rate increased nearly fourfold between 1999 and 2020.

Women are still far less likely than men to die of an illness caused by alcohol, but they also experienced a steep surge, with rates rising 2.5-fold over 20 years.

The new study, published in The American Journal of Medicine, drew on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.