What is holding back employment?

The White House and congressional Democrats have argued for weeks that the lack of child care services poses a major obstacle to the economic recovery, pressing for a massive and immediate investment to get parents back to work.

But a new economic analysis led by a prominent White House ally concludes that school and daycare closures are not driving low employment levels — blunting a key Biden administration argument in favor of its American Families Plan and undercutting the view of some Democrats that investing in child care is crucial for the country to climb out of the coronavirus recession.

“School closures and lack of child care are not holding back the recovery,” said Jason Furman, a Harvard professor who chaired the Council of Economic Advisers in the Obama administration and co-authored the analysis. “And conversely, we shouldn’t expect a short-term economic bump from reopening schools and making child care more available.”

The study — which found that the employment rate for parents of young children actually declined at a lower rate than for those without kids — adds fuel to an intense national debate about what is behind a suspected worker shortage and what policy changes are needed to accelerate Americans’ return to work as the pandemic subsides.

Here is the full Politico article by Megan Cassella and Eleanor Mueller.

Saturday assorted links

1. Have American movies lost their sense of place?

3. Ten positions chess computers have had trouble with.

4. Fear the fungi. Their computational powers may be stronger than you think.

5. “Icelandic designer Valdís Steinarsdóttir has created a range of translucent, gelatinous garments that are cast into moulds rather than cut from a pattern in a bid to eliminate waste.” Link here.

What I’ve been reading

1. Allen Lowe, “Turn Me Loose White Man”, two volumes and 30 accompanying compact discs. “Personally I accept the assumption that a great deal, if not all, of American music is rooted in forms that derive in some way from Minstrelsy.” Would you like to see that documented over the course of 30 CDs and almost 800 pp.? Would you like to know how early blues, country, gospel, jazz, bluegrass (and more) all fit together? Then this is the package for you. It is in fact of one of the greatest achievements of all time in cataloguing and presenting American culture. Here is a WSJ review.

2. Luke Burgis, Wanting: The Power of Mimetic Desire in Everyday Life. This book is the best introduction to this key Girardian concept.

3. Blake Bailey, Philip Roth: The Biography. I only read slivers and won’t finish it, because I just don’t need 800 pp. on Philip Roth. But…it’s really good. I like Picasso too, and Caravaggio (a murderer). I’ve heard, by the way, that this book will be picked up by Simon and Schuster and put back into print.

4. Martha C. Nussbaum, Citadels of Pride: Sexual Assault, Accountability, and Reconciliation. There are so many recent books on these topics, you might feel a bit weary of them all, but this is one of the best. It is rationally and reasonably argued, from first principles, and focuses on the better arguments for its conclusions. It nicely situates the legal within the philosophical, it is wise on power vs. sex, rooted in the idea of objectification, and it has at least one page on alcohol.

5. Kenneth Whyte, The Sack of Detroit: General Motors and the End of American Enterprise. How the consumer and auto safety movement helped to bring down GM.

6. Fabrice Midal, Trungpa and Vision, a biography of Chögyam Trungpa, the Tibetan Buddhist leader. I enjoyed this passage: “He never hesitated to tell the truth, even if this meant provoking the audience. At a talk in San Francisco in the fall of 1970, he began by saying: “It’s a pity you came here. You’re so aggressive.””

And this passage: “Chögyam Trungpa might have appeared, at first, sight, to be very modern and up-to-date in his approach to the teachings. He had abandoned the external signs of the Tibetan monastic tradition. He drank whiskey, smoked cigarettes, and wore Western clothes. He had a frank often provocative way with words and ignored the normal conventions of a guru.” In fact he died from complications resulting from heavy alcohol abuse.

Very good sentences

…if I argue with a higher status person, who for some reason engages with me in this context, and if my position is one seen as reasonable by the usual elite consensus, then my partner is careful to offer quality arguments, and to credit such arguments if I offer them. But if I take a position seen as against the current elite consensus, that same high status partner instead feels quite comfortable offering very weak and incoherent arguments.

That is from Robin Hanson.

Friday assorted links

1. Do employers discriminate against obese women?

2. Is bitcoin a good inflation hedge?

3. Five counties seek to leave Oregon for Idaho.

4. Will the Mormon moderation persist? Good piece.

5. New issue of Works in Progress, recommended.

6. How well is the lead hypothesis really doing? And the research is here.

7. “In Canada, it’s possible to find a man lounging on a chesterfield in his rented bachelor wearing only his gotchies while fortifying his Molson muscle with a jambuster washed down with slugs from a stubby.” (Obituary, NYT)

Population predicts regulation — but why?

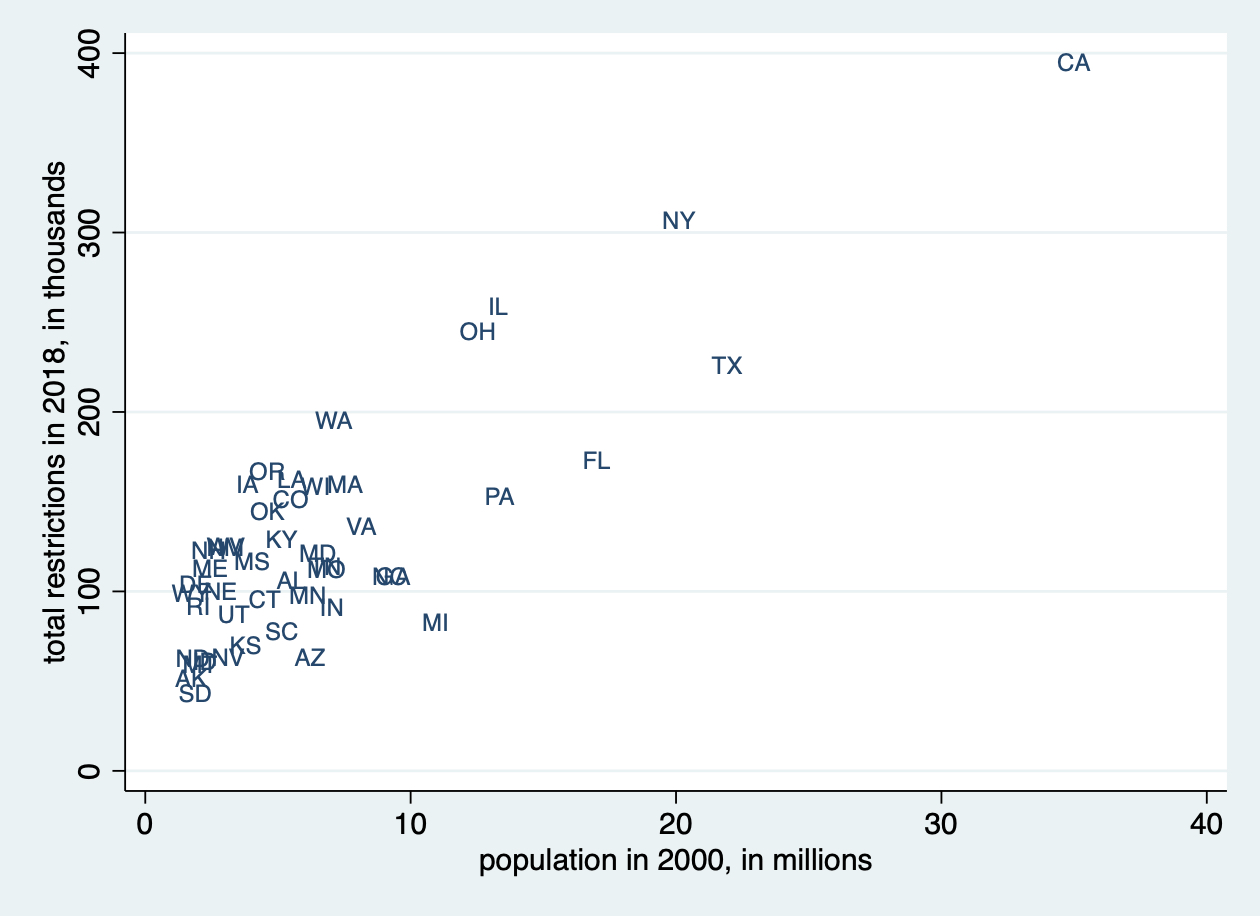

We found that across states, a doubling of population size is associated with a 22 to 33 percent increase in regulation.

The relationship between regulation and population is surprisingly robust- it also holds for Australian states and Canadian provinces, and based on the limited data we have seems to hold across countries too (for instance, the “free market” United States has 10 times as many regulations as Canada- just as it has 10 times the population).

What is less clear is why this relationship is so strong. Mulligan and Shleifer attribute it to a fixed cost of regulating; larger polities can spread this cost over more people, making the average cost of regulating cheaper, so they do it more. We note two other explanations: larger polities might have more externalities worth regulating, or if regulation produces concentrated benefits and dispersed costs, a larger population could make it harder for those harmed by regulation to organize collectively to oppose it.

That blog post is based on work from James Bailey, James Broughel and Patrick McLaughlin, the latter two my Mercatus colleagues, written by James Bailey.

Emergent Ventures winners, 14th cohort

Center for Indonesian Policy Studies, Jakarta, to hire a new director.

Zach Mazlish, recent Brown graduate in philosophy, for travel and career development.

Upsolve.org, headed by Rohan Pavuluri, to support their work on legal reform and deregulation of legal services for the poor.

Madison Breshears, GMU law student, to study the proper regulation of cryptocurrencies.

Quest for Justice, to help Californians better navigate small claims court without a lawyer.

Cameron Wiese, Progress Studies fellow, to create a new World’s Fair.

Jimmy Alfonso Licon, philosopher, visiting position at George Mason University, general career development.

Tony Morley, Progress Studies fellow, from Ngunnawal, Australia, to write the first optimistic children’s book on progress.

Michelle Wang, Sophomore at the University of Toronto, Canada, to study the causes and cures of depression, and general career development, and to help her intern at MIT.

Here are previous cohorts of winners.

Inflation and the Fed

Federal Reserve officials were optimistic about the economy at their April policy meeting as government aid and business reopenings paved the way for a rebound — so much so that and “a number” of them began to tiptoe toward a conversation about dialing back some support for the economy.

Here is more (NYT). That is yet another sign that our government (treating fiscal and monetary as a consolidated entity) made a mistake in applying too much demand stimulus. Hardly anyone said this at the time except Summers and Blanchard, and since then few have been willing to come out and admit error. There is an ex post attempt to redefine the debate by insisting inflation will not spiral out of control. Quite possibly not, but whatever your view on that question, don’t let it distract you from the actual mistake. Virtually all macroeconomic commentators in the public sphere were wrong for not realizing and stressing that too much demand stimulus was being applied. Furthermore, we ended up spending $1 trillion (!) in ways that were pretty far from optimal.

Got that? People, the rooftops are waiting.

Thursday assorted links

1.”Thomas Bagger, German diplomat and advisor to the federal president, once noted, “The end of history was an American idea, but it was a German reality.” Link here.

2. For all the mockery, we are almost at Dow 36,000.

4. “Using event study analysis of recent minimum wage increases, we find that these changes do not affect the likelihood of searching, but do lead to large yet very transitory spikes in search effort by individuals already looking for work.” Link here.

Do higher minimum wages induce more job search?

In some models job search is just about the posted wage, but I suspect that is the easiest kind of search to do. In reality, search covers multiple dimensions, for instance wage but also working conditions, such as the comfort of your job post, how much of a jerk the boss is, and so on.

If the minimum wage is hiked, the higher nominal wage will indeed induce more search, because the pecuniary gain from a good match is higher.

That said, a higher minimum wage will to some extent induce employers to lower the non-pecuniary quality of the job. At the very least, there will be more uncertainty about the non-pecuniary aspects of the job. Imagine a new job seeker: “I’ve read Gordon Tullock — now I’m wondering if they are going to turn down the air conditioner in the back room where I will be working.”

That uncertainty in fact raises the costs of job search and makes the results of that search less certain. In this regard, you can think of a higher minimum wage as a tax on job search.

If you think job search is mainly about the posted wage, you won’t be very worried about this affect. Alternatively, if you think job search is mainly about finding a good match along the non-pecuniary dimensions, you might be very worried about it indeed. And it will make it harder for minimum wage hikes to boost employment by inducing more labor search.

For this post, I am indebted to a conversation with the excellent Matthew Lilley.

The relationship between religious, civil, and economic freedoms

This paper studies the relationship between religious liberty and economic freedom. First, three new facts emerge: (a) religious liberty has increased since 1960, but has slipped substantially over the past decade; (b) the countries that experienced the largest declines in religious liberty tend to have greater economic freedom, especially property rights; (c) changes in religious liberty are associated with changes in the allocation of time to religious activities. Second, using a combination of vector autoregressions and dynamic panel methods, improvements in religious liberty tend to precede economic freedom. Finally, increases in religious liberty have a wide array of spillovers that are important determinants of economic freedom and explain the direction of causality. Countries cannot have long-run economic prosperity and freedom without actively allowing for and promoting religious liberty.

Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Wednesday assorted links

My Conversation with Pierpaolo Barbieri

Here is the audio, visual, and transcript. Here is part of the summary:

Pierpaolo joined Tyler to discuss why the Mexican banking system only serves 30 percent of Mexicans, which country will be the first to go cashless, the implications of a digital yuan, whether Miami will overtake São Paolo as the tech center of Latin America, how he hopes to make Ualá the Facebook of FinTech, Argentina’s bipolar fiscal policy, his transition from historian to startup founder, the novels of Michel Houellebecq, Nazi economic policy, why you can find amazing and cheap pasta in Argentina, why Jorge Luis Borges might be his favorite philosopher, the advice he’d give to his 18-year-old self, his friendship with Niall Ferguson, the political legacy of the Spanish Civil War, why he stopped sending emails from bed, and more.

Here is just one bit:

COWEN: Why did Argentina’s liberalization attempt under Macri fail?

BARBIERI: That’s a great question. There’s a very big ongoing debate about that. I think that there was a huge divergence between fiscal policy and monetary policy in the first two years of the Macri administration.

The fiscal consolidation was not done fast enough in 2016 and 2017 and then needed to accelerate dramatically after the taper tantrum, if you want to call it, or perceived higher global rates of 2018. So Macri had to run to the IMF and then do a lot of fiscal consolidation — that hadn’t been done in ’16 and ’17 — in’18 and ’19. Ultimately, that’s why he lost the election.

Generally speaking, that’s the short-term electoral answer. There’s a wider answer, which is that I think that many of the deep reforms that Argentina needed lack wide consensus. So I think there’s no question that Argentina needs to modify how the state spends money and its propensity to have larger fiscal deficits that eventually need to be monetized. Then we restart the process.

There’s a great scholar locally, Pablo Gerchunoff, who’s written a very good paper that analyzes Argentine economic history since the 1950s and shows how we move very schizophrenically between two models, one with a high exchange rate, where we all want to export a lot, and then when elections approach, people want a stronger local currency so that we can import a lot and feel richer.

The two models don’t have a wide acceptance on what are the reforms that are needed. I think that, in retrospect, Macri would say that he didn’t seek enough of a wider backing for the kind of reforms that he needed to enact — like Spain did in 1975, if you will, or Chile did after Pinochet — having some basic agreements with the opposition that would outlive a defeat in the elections.

And:

COWEN: The best movie from Argentina — is it Nine Queens, Nueve reinas?

BARBIERI: It is a strong contender, but I would think El secreto de sus ojos, The Secret in Their Eyes, is my favorite film about Argentina because of what it says about the very difficult period of modernization, and in particular, the horrors of the last military regime that marked us so much that it still defines our politics 50 years since.

Recommended.

Born to be Managers?

The paper’s subtitle is “Genetic Links between Risk-Taking and the Likelihood of Holding Managerial Positions.” It is hard for me to verify or assess this kind of result, but I pass it along for its interest:

Do genes determine who will become managers? Using the UK Biobank data, we study the phenotypic and genetic correlations between the likelihood of holding managerial positions and physical, cognitive, and mental health traits (n = 297,591). Among all traits we examine, general risk tolerance and risky behaviors (e.g., automobile speeding and the number of sexual partners) have the strongest phenotypic and genetic correlations with holding managerial positions. For example, the genetic correlation between automobile speeding and being managers is 0.39 (P = 3.94E-16). Additionally, the genetic correlations between risk-taking traits and being managers are stronger for females. Genome-wide association study (GWAS) shows holding managerial positions is associated with rs7035099 (ZNF618, 9q32), which has been linked to risk tolerance and adventurousness. Overall, our results suggest individuals with risk-taking-related genes are more likely to become managers. To the best of our knowledge, this paper is the first GWAS of the genetic effects on leadership.

That is from a new paper by Jinjie Lin and Bingxin Zhao. Via a loyal MR reader.

It feels like we are living in a science fiction novel

That is the theme of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

Now, for the first time in my life, I feel like I am living in a science fiction serial.

The break point was China’s landing of an exploratory vehicle on Mars. It’s not just the mere fact of it, as China was one of the world’s poorest countries until relatively recently. It’s that the vehicle contains a remarkable assemblage of software and artificial intelligence devices, not to mention lasers and ground-penetrating radar.

There is a series of science fiction novels about China in which it colonizes Mars. Published between 1988 and 1999, David Wingrove’s Chung Kuo series is set 200 years in the future. It describes a corrupt and repressive China that rules the world and enforces rigid racial hierarchies.

It is striking to read the review of the book published in the New York Times in 1990. It notes that in the book “the Chinese somehow regained their sense of purpose in the latter half of the 21st century” — which hardly sounds like science fiction, the only question at this point being why it might have taken them so long. The book is judged unrealistic and objectionable because its “vision of a Chinese-dominated future seems arbitrary, ungrounded in historical process.” The Chung Kuo books don’t reflect my predictions either, but it does seem that reality has exceeded the vision of at least one book critic.

I also consider Asimov, Dogecoin, and Stephenson at the link.