Category: Current Affairs

Big Beautiful Bill critiques

So far I am not finding them very impressive.

To be clear, there are many things — big things — I do not like about the bill. I would sooner cut Medicare than Medicaid (that said, I do not find the idea of cutting health care spending outrageous per se). The corporate rate ends up being too low, given the budget situation. No taxes on tips and overtime is crazy and cannot last, given the potential to game the system, plus those are not efficient tax changes.

I strongly suspect that if I knew more of the bill’s details (e.g., what exactly is the treatment of nuclear power in the current version?), I would have more complaints yet. I do not wish to boost taxes on solar power. Veronique de Rugy criticizes the underlying CEA projections.

That all said, doing the budget is not easy, especially these days. Maybe I have read fifteen or so critiques of BBB, and have not yet seen one that outlines which spending cuts we should do. Yet comparative analysis is the essence of economics, or indeed of policy work more generally. In that sense they have not yet produced critiques at all, just complaints. Alternatively, the critics could outline all the tax hikes that would put the budget on a sustainable path, but I do not see them doing that either. Again, no comparative analysis.

If you don’t want to cut health care spending, what do you want to cut? I am willing to cut health care spending, preferring to start with richer and older people to the extent that is possible.

You can always spend more on health care and save more lives and prevent some suffering. But what is the limiting principle here? Simply getting angry about the fact that lower health care spending will have some bad outcomes is more a sign of a weak argument than a strong argument. Again, a strong argument needs comparative analysis and some recognition of what is the limiting principle on health care spending. I am not seeing that. I am seeing anger over lower health care spending, but no endorsements of higher health care spending. I guess we are supposed to be doing it just right, at least in terms of the level?

It is commonly noted that the depreciation provisions and corporate cuts will increase the deficit, but how many of the critics are noting they are also likely to increase gdp (but by enough to prove sustainable?)? I write this as someone who thinks the proposed Trump corporate tax rate is too low, but I am willing to recognize the trade-offs here.

Another major point concerns AI advances. A lot of the bill’s critics, which includes both Elon and many of the Democratic critics, think AI is going to be pretty powerful fairly soon. That in turn will increase output, and most likely government revenue. Somehow they completely forget about this point when complaining about the pending increase in debt and deficits. That is just wrong.

It is fine to make a sober assessment of the risk trade-offs here, and I would say that AI does make me somewhat less nervous about future debt and deficits, though I do not think we should assume it will just bail us out automatically. We might also overregulate AI. But at the margin, the prospect of AI should make us more optimistic about what debt levels can be sustained. No one is mentioning that.

It also would not hurt if critics could discuss why real and nominal interest rates still seem to be at pretty normal historical levels, albeit well above those of the ZIRP period.

Overall I am disappointed by the quality of these criticisms, even while I agree with many of their specific points.

Austin Vernon on taxes on solar (from my email)

I think your question about new taxes on solar and wind is an interesting one, and increasing taxation has been an ongoing process for years.

Some of these tax increases are normal, like ending property tax exemptions. These taxes don’t impact project economics too severely, and the breaks create a lot of ill will at the local level.

Solar has seen constant tax increases and quotas on imported panels. Uncompetitive domestic producers, other competing energy sources, anti-trade folks, and China hawks all favor these taxes. The important metric is that buying panels in the US is 2x-3x more expensive per watt than in the rest of the world.

Solar panel factories are easy to build, and technology changes quickly. There is a Dutch boy and the dam effect. We constantly have to add new tariffs on different countries and new technologies (although foreign production from US-owned companies has generally been exempt). These tariffs have to get stiffer to maintain the balance.

A recent change was that the IRA finally led everyone to start building factories in the US. An absolute avalanche of panel factories is/was on the way with less activity for cells, wafers, and polysilicon. These factories might be viable without subsidies considering US panel prices. Most of the interest groups listed don’t appreciate this outcome, especially because many are Chinese-owned factories. Foreign Entity of Concern content and ownership penalties are the obvious solution as the next hole to put a finger in because many subcomponents would still be imported and the general kludge laws like that add.

The solar installation lobby has been satisfied with tax credits that counteract some of the high panel costs. These rules tend to discourage new technology in the fine print and skew incentives. Simpler, denser solar farm designs make sense once panels are cheap. There is no reason to make the switch if panels are expensive and the tax credit is based on the total install cost. Roughly 90% of US utility-scale installations have trackers that add cost but increase per panel output. In China, there are almost no trackers. There are also some nasty effects in the residential business that encourage complex financial products over streamlining construction and permitting.

It is an interesting crossroads where the tax credits are gone, and there is now a reason to have a more direct confrontation on panel cost. The battery industry is in the early stages of a similar conflict, but it seems like they might retain the deal with the devil and keep tax credits for now.

The world’s most expensive toll?

A bridge connects Copenhagen and Malmo, and now the price is higher:

…the basic price for a one-way car journey across the bridge has been jacked up to 510 Danish kroner, or £58. For the largest vans, it is the equivalent of £218.

Research by Sydsvenskan, a regional newspaper in southern Sweden, suggests this is by far the most expensive bridge toll on the planet, costing about twice as much as its nearest rivals in Japan and Canada…

Despite the vehicle toll, the total number of people crossing the Oresund by car, train or ferry hit a record 38 million last year, equivalent to about 105,000 trips a day. A one-way railway journey between central Copenhagen and Malmo typically costs only £13.

Here is the full story from The Times. I find this intrinsically interesting, but I also would like to make a simple point. If you are assessing the optimal toll here, claims that “the higher toll limited congestion,” or “the higher toll diminished the number of car trips” are not dispositive. They are relevant information, but one also has to measure whether gains from trade across the two polities went down as well. Otherwise, you do not have much of a conclusion.

Privatize Federal Land!

I’ve long advocated selling off some federal land—an idea that reliably causes mass fainting spells among the enlightened. How could we possibly part with our national patrimony, our land, our sacred wilderness? Calm down. Most of this “public land” is never used by the public. Selling some of it would actually make it more accessible and useful to real people.

Moreover, most of you wailing about selling some Federal land are probably very happy we sold the “public” airwaves for your private cell phone use. Privatizing the airwaves made them much more useful to the public. (Thank you Reed!).

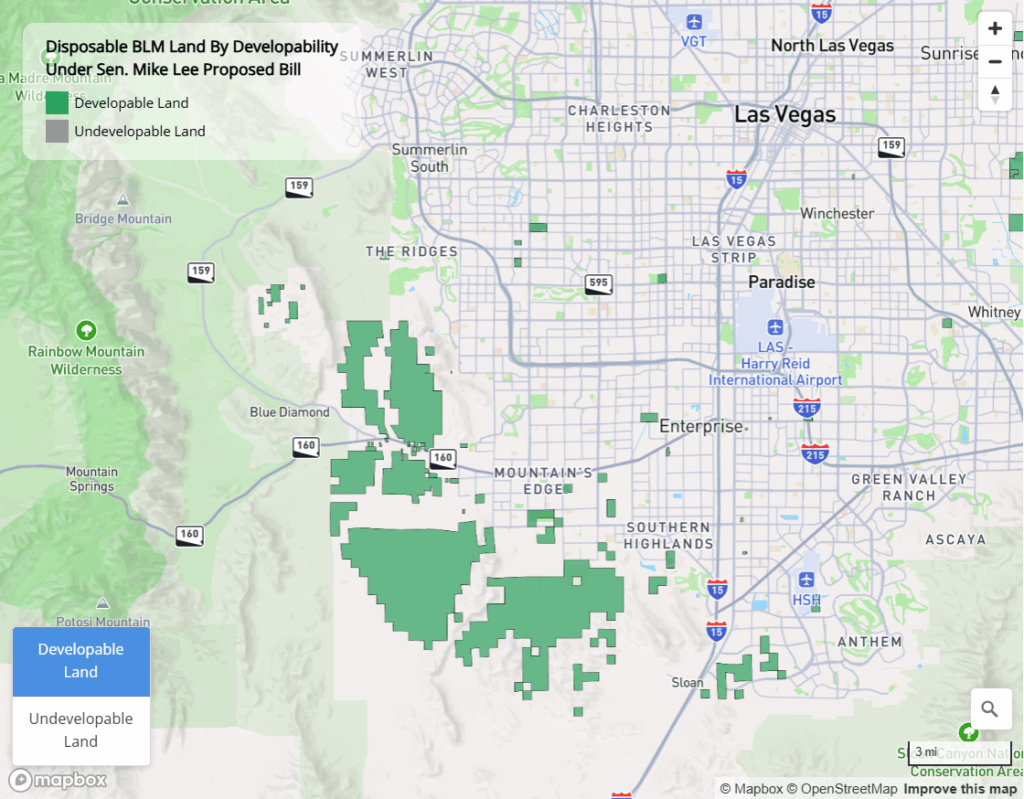

AEI has an excellent map of the lands that could be sold and developed in the Mike Lee bill. Here’s their conclusion:

The data show a significant opportunity. Our analysis finds that developing just 135-180 square miles of the most suitable BLM land, a minuscule fraction of the total, could yield approximately 1 million new homes over ten years. This would substantially address the West’s housing shortage while generating an estimated $15 billion for the U.S. Treasury from land sales.

Here’s an example of the some of the land potentially developable around Las Vegas.

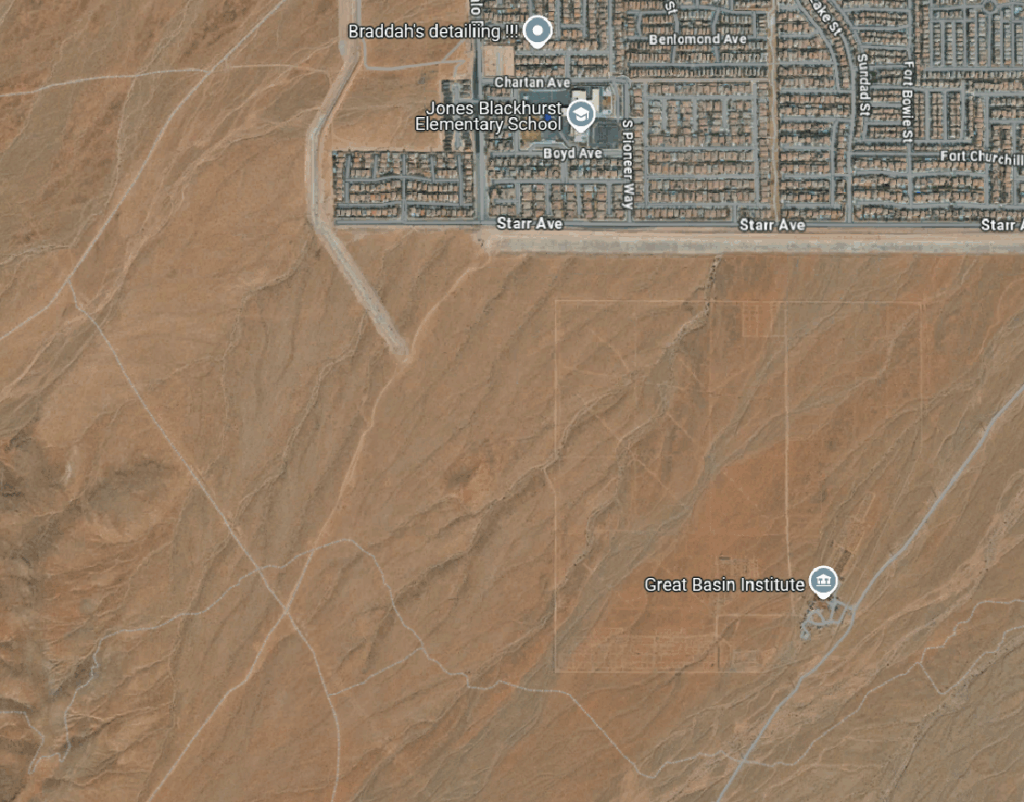

Here’s a Google satellite image of the bit around Mountain’s Edge. Enjoy your fishing on these public lands!

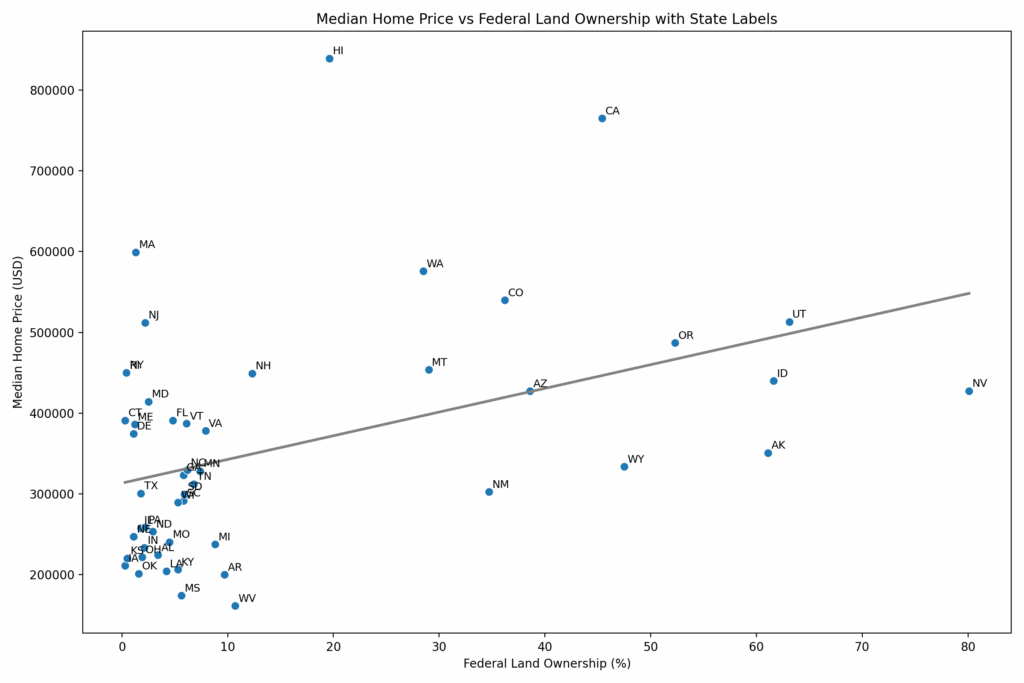

And here’s a very crude but useful scatter plot showing the correlation between median home prices in a state and Federal land ownership. Should home prices in Utah (63.1% Federally owned) really be 71% higher than in Texas (1.8% Federally owned)? Of course, Texas is famously an urban hellscape with no parks, no open space, and nowhere to hunt or fish.

C’mon British people, you can do better than this…

I’ve seen estimates that thirty people a day are arreested in the UK for things they say on social media. Other anecdotes of varying kinds continue to pile up:

Describing a middle-aged white woman as a “Karen” is borderline unlawful, a judge has said amid a bitter row at a mental health charity.

The slang term, used increasingly since the pandemic, refers to middle-aged white women who angrily rebuke those they view as socially inferior. Sitting in an employment tribunal, a judge has now said that the term is pejorative because it implies the woman is excessively and unreasonably demanding.

The woman who used the term nonetheless was acquitted, though barely. Here is the article from Times of London. And this:

The government’s new Islamophobia definition could stop experts warning about Islamist influence in Britain, a former anti-extremism tsar has warned.

Lord Walney said that a review being carried out by Angela Rayner’s department should drop the term Islamophobia, or risk “protecting a religion from criticism” rather than protecting individuals.

Ministers launched a “working group” in February aimed at forming an official definition of what is meant by Islamophobia or anti-Muslim hatred within six months.

Here is The Times link. British people, it is not just J.D. Vance who is upset. You are embarrassing yourselves with all this! Please stop. Even enemies of free speech think you are going about this in a pretty stupid way.

Detroit helicopter drop of cash

The money drop was apparently the last wish of the owner of a nearby car wash. Knife said the man recently died due to Alzheimer’s Disease and his funeral was Friday.

Despite the mad dash for free cash, the incident remained peaceful, if hectic, Knife said.

“There was no fighting, none of that,” she said. “It was really beautiful.”

…Witnesses said a helicopter hovering in the area of Gratiot Avenue and Conner Street dropped thousands of dollars in cash onto the pedestrians below, bringing a sudden and surreal burst of joy to a hot Friday afternoon in east Detroit.

Lisa Knife, an employee at the nearby Airport Express Lube & Service, 10490 Gratiot, estimated that thousands of dollars were tossed from the chopper.

Here is the full story, via Edward Craig.

The military culture that is German

Pistorius must grapple with a procurement bureaucracy that once took seven years to select a new main assault rifle and more than a decade to procure a helmet for helicopter pilots. He will have to oversee an enormous ramp-up by an arms industry already struggling with capacity. And billions must go towards tasks such as upgrading barracks, some of which are in “disastrous” shape with crumbling plaster and mould, according to the armed forces watchdog.

Here is more from the FT.

Turkey fact of the day

Real interest rates, which subtract inflation from central bank policy rates, have been negative for a remarkable 13 of the 22 years that Erdoğan has been in power, according to FT research. This helped spur growth, boost incomes and sustain a construction boom. It also laid the foundation for an economic crisis.

By late 2022, real rates had fallen to minus 75 per cent. By mid-2023, fuelled by high government spending following a devastating earthquake and pre-election fiscal splurge, the economy was overheating. Inflation was running at 60 per cent, the lira was in freefall and Turkey had a current account deficit equivalent to almost 6 per cent of GDP but had negative net reserves of about minus $60bn.

Here is more from John Paul Rathbone at the FT. I would want to know more about what actual net borrowing rates have been, all factors considered. Still, this is quite something, even if it is only an interest rate on paper, so to speak.

Who in California opposes the abundance agenda?

Labor unions are one of the culprits, environmental groups are another:

Hours of explosive state budget hearings on Wednesday revealed deepening rifts within the Legislature’s Democratic supermajority over how to ease California’s prohibitively high cost of living. Labor advocates determined to sink one of Newsom’s proposals over wage standards for construction workers filled a hearing room at the state Capitol mocking, yelling, and storming out at points while lawmakers went over the details of Newsom’s plan to address the state’s affordability crisis and sew up a $12 billion budget deficit.

Lawmakers for months have been bracing for a fight with Newsom over his proposed cuts to safety net programs in the state budget. Instead, Democrats are throwing up heavy resistance to his last-minute stand on housing development — a proposal that has drawn outrage from labor and environmental groups in heavily-Democratic California.

Here is the full story, via Josh Barro. To be clear, I am for the abundance agenda.

Flying on Frying Oil

The ever-excellent Matt Levine points us to the amusing economic policies that connect the international jet-set to Malaysian street hawkers of fried noodles. The EU and the US have created strong economic incentives to create sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) and a good way to do this is to recycle used cooking oil (UCO). What could be better, right? Take a waste product and turn it into jet fuel! The EU and US policies, however, are so strong that all the EU and US used cooking oil cannot meet the demand. Here’s a great sentence, “Europe simply cannot collect enough used cooking oil to fly its planes.”

In the US, credits under the Inflation Reduction Act can account for up to $1.75 to $1.85 per gallon of SAF. Meanwhile cooking oil is subsidized in some  parts of the world. The result?

parts of the world. The result?

It turns out that restaurants, street food stalls and home cooks in Malaysia — which is “among the world’s leading suppliers of both UCO and virgin palm oil” — will pay less for fresh cooking oil than the international market will pay for used cooking oil. Fresh cooking oil is more useful to cooks than used cooking oil (it tastes better), but it is less useful to refiners and airlines than used cooking oil (it doesn’t reduce their carbon impact). Also fresh cooking oil is subsidized by the government in Malaysia: “Subsidised cooking oil sells for RM2.50 per kg versus the UCO trading price of up to RM4.50 per kg.” So if you run a restaurant, you can buy fresh cooking oil for about $0.60 (USD), use it to fry food a few times, and then sell it to a refiner for $1, which is a nice little subsidy for the difficult, risky, low-margin business of running a restaurant.

The noodle hawkers in Kuala Lumpur are getting a nice little bump in profit but who is going stall to stall to check that the oil is in fact used? And what counts as used? One fry or two? Clever entrepreneurs have cut out the middleman. Virgin palm oil can be substituted for used cooking oil and voila! Sustainable aviation fuel is contributing to deforestation in Malaysia. Malaysia exports far more “used” cooking oil than oil that it uses. No surprise.

All of this illustrates a broader point: externalities suggest policy interventions may improve outcomes but markets are complex and politics is blunt. It’s easy to make things worse. If intervention is necessary, a uniform carbon tax beats a patchwork of production-specific subsidies. A price is a signal wrapped up in an incentive. Send everyone the same signal and the same incentive to ensure that the cheapest emissions are cut first and total costs are minimized.

Crucially, a carbon tax rewards any effective solution, even ones a planner would never think of–lighter planes and cleaner fuels sure but also operational tweaks like jet washes. In contrast, subsidies tether policy to specific technologies, like used cooking oil. That invites rent-seeking and inefficiency.

Tax carbon, not inputs. Avoid games with paperwork. One verification point at the fuel supply point is simpler than tracing global waste-oil chains. Don’t subsidize the fry oil and audit the street hawkers. Tax the emissions.

How constrained is the NYC mayor?

I thought to ask o3, here is the opening of its answer:

New York City has a “strong-mayor / council” system, but the City Charter, state law and an array of watchdog institutions deliberately fragment power. In practice the mayor can move fastest on implementation—issuing executive orders, running the uniformed services, writing the first draft of the budget, and appointing most agency heads—yet almost every strategic decision runs into at least one institutional trip-wire.

He does appoint all police commissioners and has direct control over the police. The mayor also has line item veto authority, although that can be overriden by the City Council. The entire response is of interest. More generally, who will and will not feel welcome in the city after this result?

Germany Italy fact of the day

Germany and Italy hold the world’s second- and third-largest national gold reserves after the US, with reserves of 3,352 tonnes and 2,452 tonnes, respectively, according to World Gold Council data. Both rely heavily on the New York Federal Reserve in Manhattan as a custodian, each storing more than a third of their bullion in the US. Between them, the gold stored in the US has a market value of more than $245bn, according to FT calculations…

“We need to address the question if storing the gold abroad has become more secure and stable over the past decade or not,” Gauweiler told the FT, adding that “the answer to this is self-evident” as geopolitical risk had made the world more insecure.

In case you wish to comment on very recent events

Comments are open…

Who needs robots?, China fact of the day

A hotel in southwestern China’s megacity of Chongqing has come under fire for using red pandas to deliver morning wake-up calls to guests, sparking controversy and raising fresh concerns about the welfare of endangered wildlife and customer safety.

Located near the Chongqing Wild Animal World, the hotel offers a so-called “red panda morning call” service, where staff lead red pandas into guests’ rooms to greet them in the morning. Guests can feed, stroke, and take photos with the animals — some of whom were filmed exploring the hotel rooms and wandering across beds.

In addition to red panda-themed rooms, the hotel features accommodation with up-close contact with ring-tailed lemurs, albeit this time outdoors.

Here is the full story, via Jonathan Cheng.

Of Course We Should Privatize Some Federal Land (but probably won’t)

The Federal government controls a ridiculous amount of land in the West including more than half of Oregon, Utah, Nevada, Idaho and Alaska and nearly half of California, Arizona, New Mexico and Wyoming. See the map (PDF). The vast majority of this land is NOT parks!!! It is time for a sale to raise some funds and improve the efficiency of land allocation.

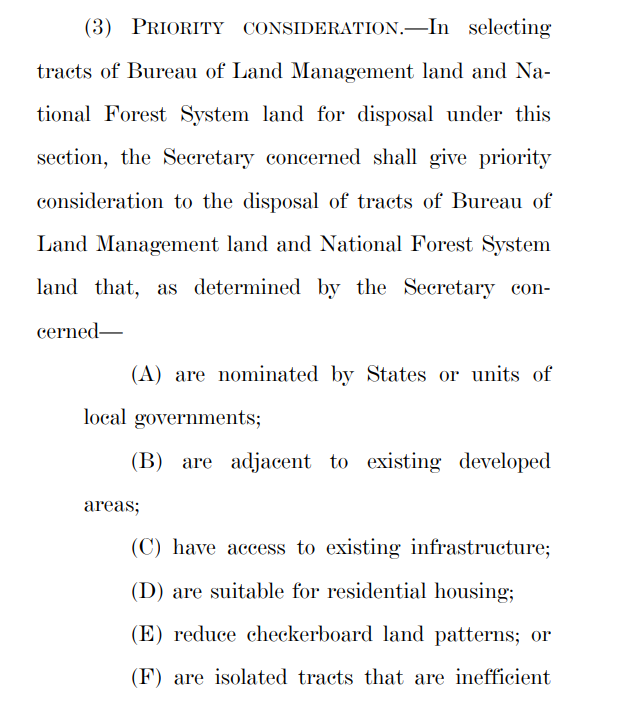

The conservative Mike Lee has a bill that would allow some sales. Great! The only problem with the bill is that it is loaded down with restrictions and qualifications. For example, there is a cap of 0.75% on total sales–that’s right, the land sales are capped at less than 1% of the total Federal land and that is a high cap because most of the rules prohibit any sale. The sales that are allowed have to be nominated by state or local governments, must be adjacent to developed areas and close to infrastructure. Moreover, the land can only be use for housing. Lyman Stone has a thread going into even more detail. The very modest goal–as you can see at right–is to rationalize some checkerboard land patterns.

The conservative Mike Lee has a bill that would allow some sales. Great! The only problem with the bill is that it is loaded down with restrictions and qualifications. For example, there is a cap of 0.75% on total sales–that’s right, the land sales are capped at less than 1% of the total Federal land and that is a high cap because most of the rules prohibit any sale. The sales that are allowed have to be nominated by state or local governments, must be adjacent to developed areas and close to infrastructure. Moreover, the land can only be use for housing. Lyman Stone has a thread going into even more detail. The very modest goal–as you can see at right–is to rationalize some checkerboard land patterns.

Even so, the bill is probably doomed. Just mentioning federal land sales triggers a moral panic, as if someone proposed auctioning off Yellowstone. Supposed conservatives like Lomez are fueling this hysteria (e.g. here, here and here). It’s nonsense. Here and here is the type of land we are actually talking about—notice the difference?

As Matt Darling pointed out, this is Everything Bagel Liberalism from Conservatives—a bloated mess of proceduralism that empowers special interests and kneecaps supply.

If we can’t even sell Federal scraps then we’ve abandoned any pretense of governing in the public interest. We should be building entirely new cities–freedom cities!–not whining about fishing and hunting on scraps of scrub. This is exactly the same as urban NIMBYs who lobby to save “historic” parking lots. Pathetic. The federal land monopoly is not sacred. Let it go. This is where the rubber hits the road: if MAGA means anything beyond vibes and grievance, it should mean cutting red tape and unlocking land for Americans to own and build upon.