Category: Current Affairs

Why does renovating the Fed cost so much?

Here is a good WSJ piece on that question. Excerpt:

For example, members of the fine arts commission in 2020 recommended that the Fed use more marble to better match the original buildings. The Fed had initially proposed using more glass in an effort to represent the Fed’s transparency, according to the commission’s meeting minutes. The Fed amended the design to incorporate more marble.

To be clear, I am fine with an unabashedly elitist approach to designing or redesigning a central bank building, at least provided one’s domestic politics is able to sustain such a thing. I am glad for instance that the Cleveland Fed is quite a nice building, and I wish more DC architecture were of comparable quality, noting that these days we are not very good at constructing Beaux Arts buildings, and for DC modernist styles do not always fit the surroundings very well, thus creating a broader dilemma.

Horseshoe Theory: Trump and the Progressive Left

Many of Trump’s signature policies overlap with those of the American progressive left—e.g. tariffs, economic nationalism, immigration restrictions, deep distrust of elite institutions, and an eagerness to use the power of the state. Trump governs less like Reagan, more like Perón. As Ryan Bourne notes, this ideological convergence has led many on the progressive left to remain silent or even tacitly support Trump policies, particularly on trade.

“[P]rogressive Democrats like Senator Elizabeth Warren have chosen to shift blame for Trump’s tariff-driven price hikes onto large businesses. Last week, they dusted off—and expanded—their pandemic-era Price Gouging Prevention Act. While bemoaning Trump’s ‘chaotic’ on-off tariffs, their real ire remains reserved for ‘greedy corporations,’ supposedly exploiting trade policy disruption to pad prices beyond what’s needed to ‘cover any cost increases.’

…The Democrats’ 2025 gouging bill is broader than ever, creating a standing prohibition against ‘grossly excessive’ price hikes—loosely suggested at anything 20 percent above the previous six-month average—but allowing the FTC to pick its price caps ‘using any metric it deems appropriate.’

…Instead of owning the pricing fallout from his trade wars, President Trump can now point to Democratic cries of ‘corporate greed’ and claim their proposed FTC crackdown proves that it’s businesses—not his tariffs—to blame for higher prices.

If these progressives have their way, the public debate flips from ‘tariffs raise prices’ to ‘the FTC must crack down on corporate greed exploiting trade policy reform,’ with Trump slipping off the hook.”

Trump’s political coalition isn’t policy-driven. It’s built on anger, grievance, and zero-sum thinking. With minor tweaks, there is no reason why such a coalition could not become even more leftist. Consider the grotesque canonization of Luigi Mangione, the (alleged) murderer of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson. We already have a proposed CA ballot initiative named the Luigi Mangione Access to Health Care Act, a Luigi Mangione musical and comparisons of Mangione to Jesus. The anger is very Trumpian.

A substantial share of voters on the left and the right increasingly believe that markets are rigged, globalism is suspect, and corporations are the real enemy. Trump adds nationalist flavor; progressives bring the regulatory hammer. The convergence of left and right in attacking classical liberalism– open markets, limited government, pluralism and the basic rules of democratic compromise–is what worries me the most about contemporary politics.

USA fact of the day

Federal Reserve Board operating expenses have *quadrupled* from 2004 to 2023, reaching ~$1 billion in 2023, according to the Annual Reports of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

That is from Jon Hartley. It is of course correct that the other effects of the Fed far outweigh the size of these expenditures. Nonetheless, it is worth asking, given these numbers, whether the system in place is generating good decisions. That in turn said, we do not currently have an “appropriate set of askers.”

Gross(ery) Confusion

Zephyr Teachout’s NYTs op-ed on grocery store prices is poorly argued.

The food system in the United States is rigged in favor of big retailers and suppliers in several ways. Big retailers often flex their muscles to demand special deals; to make up the difference, suppliers then charge the smaller stores more.

Let’s be clear about what is actually going on. Costco offers its suppliers lower prices in return for bigger orders. There is nothing anti-competitive about volume discounting. Moreover, are firms dismayed or are they eager to sell to big, bad Costco? Google AI gives a good answer:

…firms are eager to sell to Costco because of the immense potential for sales and brand exposure, but they must be prepared to meet stringent requirements, negotiate competitive pricing, and be able to handle high volume and demanding logistics.

Would Americans be better off without Costco? Doubtful given that more than one-quarter of all Americans pay for a Costco membership (either individually or as a family).

Teachout’s idea that suppliers “make up the difference” by charging smaller stores more is also economically incoherent. Profit-maximizing firms already charge what the market will bear. If Costco’s volume justifies a discount, that doesn’t mean suppliers can or should charge higher prices to other buyers. Yes, there are models where costs change with volume but costs could go down with volume and, in any case, those models don’t rely on the folk theory of “making up the difference.”

That’s one of the subtler mistakes. Here’s a more glaring one:

Consider eggs. At the independent supermarket near my apartment, the price for a dozen white eggs last week was $5.99. At a major national retailer a few blocks away, it was $3.99. (For an identical box of cereal, the price difference was $3.) Any number of factors may contribute to a given price, but market power is a particularly consequential one.

Read that again: the firm allegedly abusing market power is the one charging less.

It gets stranger:

New York City has a strong price gouging law on the books, which forbids anyone — suppliers and retailers — from jacking up prices during a state of emergency unless the seller’s own costs have gone up accordingly. The city couldn’t have stopped the bird flu that devastated flocks, but maybe it can stop suppliers from cynically exploiting a crisis to justify exorbitant prices.

This makes two errors. First, she acknowledges it’s not gouging if costs rise—then cites egg prices rising due to the bird flu devastating flocks. That’s literally a textbook case of a supply shock. Maybe some firms exploited the crisis—but eggs rising in price after millions of chickens are killed is the best example you’ve got???

Second, within the span of a few paragraphs, the op-ed veers from claiming large retailers charge prices that are unfairly low to blaming them for charging prices that are too high. I’m surprised she didn’t go for the trifecta and accuse them of colluding to charge the same price.

The America vs. Europe thing, again

From my latest column at The Free Press:

I worry much more about Europe in the longer run. Let’s consider how some of the most important comparisons between America and Europe are likely to change over the next 20 years.

Two of America’s biggest problems are obesity and opioid addiction, with opioid deaths running at about 54,000 a year. Yet both of those problems are getting better. GLP-1 drugs will help us beat back obesity, and finally opioid deaths have begun to decline. If this follows the path of previous drug epidemics, the decline will continue and perhaps accelerate.

More generally, we are entering a new age of fantastic biomedical innovations. These advances likely will help Americans more than Europeans, as Europeans are more likely to be in good shape to begin with, which is why Americans are more likely to need new and better treatments. That is, of course, a ding on America, but it will matter less as time passes.

One major advantage of America is likely to increase with time, and that is one of scale. Americans do things big, think big, and have created some of the world’s largest companies, most obviously in the tech sector, where size is often rewarded. You can see this in the stock market valuations of those tech companies, including Nvidia, which at its current $4 trillion or so valuation is worth more than the entire German stock market. Europe shows few if any signs of catching up in this area, or of having a major presence in the commercial spaces for artificial intelligence. If anything, EU regulations go out of their way to prevent Europe from excelling at tech.

Is tech likely to stop growing in economic and cultural influence? Have we reached peak application for current and future AI models? You can guess at the right answers to all of those questions. They imply that America’s economic lead over Europe will widen.

The brain drain from Europe (and other regions) to the United States seems to be accelerating in the areas of tech and AI, most of all for young people. If you want to do a big, successful start-up, you probably should move to America. End of story. America has major and growing companies in these areas, full of foreigners, and Europe does not.

Of course, a lot of that talent will not pay off right away. Not all of those smart and ambitious individuals will have big commercial hits at the age of 22. But more and more of them will by the age of 40. Europe has lost an increasing number of these people, and won’t be getting most of them back. The continent feels a bit of pain now, but the talent differential will de facto increase, if only due to the mere passage of time and the rising productivity of those people. It is not just about more people leaving; rather, those who already have moved to America will make a bigger and bigger difference over the next 10 to 15 years.

And:

The more general lack of European economic dynamism also is an issue that worsens with time. One recent economic study found that “Europeans switch jobs much less frequently, and restructuring is much rarer.” That is, of course, a problem, but in the short run the associated difficulties are not so large. If your economy remains static, after a year of progress elsewhere it is only missing out on so much beneficial change. After five years it is missing out on much more, and after 10 years much more yet. The more static and less dynamic nature of European economies naturally increases in size as a problem with the passage of time.

Population aging and low birth rates are another problem that will make it harder for Europe to catch up. The U.S. total fertility rate is about 1.63, whereas in the European Union it is about 1.38. Over time, this will make it harder for Europe to afford their current system of pensions. The major European populations also will be older than the American population, and probably as a result less innovative. This difference has only started to bite, and it is likely to grow in import.

I consider some other important issues, such as immigration, at the link.

Can we internalize the externalities from public bathrooms?

Throne’s solution relies on gating access to their facilities, but in a way the company’s founders insist means they remain accessible to all. Users are associated with a unique identifier via an app or text message, so dumbphones work too. (In rare cases, those who don’t have a phone can get a keycard.) If you mess up the bathroom, you’re given a warning, and if you’re a repeat offender, you could lose your potty privileges. It’s similar to an Uber rider score, says Throne Labs Chief Executive Fletcher Wilson.

Throne bathrooms also have smoke sensors to detect if someone smokes in them, and occupancy sensors. They limit any given session to 10 minutes. After a warning, the doors will pop open. Everyone is asked upon entry to rate the cleanliness of the bathroom. If a bathroom needs cleaning, a Throne employee is dispatched for a cleanup.

Here is more from the WSJ. Via Adam B.

Naveen Nvn’s ideological migration (from my email)

I started following American politics only in 2010/2011, which is two years after his [Buckley’s] death, and I was in India at that time.

Plus, I was very liberal at that time.

Around 2018-19ish, I was pushed into a centrist stance because I was appalled by wokeness, especially on campuses. I was in graduate school in the US at that time. Although I didn’t experience wokeness advocacy in the classroom except two or three incidents, I saw signs of wokeness on campus a lot. But even then, I was quite libertarian on how universities ought to handle campus politics.

I picked up God and Man at Yale around this time because wokeness was my primary concern.

I’ve always known that conservatives love that book. I assumed it would be a defense of free inquiry and against universities having a preferred ideology.

However, to my surprise, in the book, he argued explicitly that Yale was neglecting its true mission and it should uphold its “foundational values,” as he put it. I assumed he would be promoting a libertarian outlook on campus politics, but he was arguing the opposite.

He said Yale and other elite universities should incorporate free markets and traditional perspectives directly into the curriculum because they are betraying a contract that the current alumni and the administration have with the founders of the universities. It was a pretty shocking advocacy of conservatism being imposed on the students, and I didn’t like that at all.

But later on, around 2020-ish, I became a conservative (thanks to you; more on that in the link below). But even as late as early 2023, I still held a libertarian view on academic freedom and campus politics.

(You may be interested in a comment I left on your ‘Why Young People Are Socialist’ post yesterday, in which I shared how I was once a liberal, then turned centrist, and how I finally turned conservative. You are a major influence.)

But after Oct 7, all of that changed quite fast. Watching the pro-Hamas protests on campuses that started the very next day after October 7, before even one IDF soldier set foot on Gaza, I immediately thought about God and Man at Yale. I wanted to go back and re-read God and Man at Yale.

Everything I’ve witnessed after Oct 7 — Harvard defending Claudine Gay, Harvard explicitly stating they’re an “international institution” and not an American institution, DEI, anti-White, anti-Asian discrimination, etc. has convinced me that WFB Jr. was right.

Elite universities ought to be promoting free markets and pro-American, pro-Western views. I don’t believe we should have a completely libertarian approach to academic freedom. That’s untenable in this day and age. (Again, demographics is destiny, even within organizations.)

I’ve become significantly less libertarian on a wide range of issues compared to where I was just two years ago, and not just on academic freedom/university direction.

So yes, WFB Jr. has influenced me on this idea.

David Brooks on the AI race

When it comes to confidence, some nations have it and some don’t. Some nations once had it but then lost it. Last week on his blog, “Marginal Revolution,” Alex Tabarrok, a George Mason economist, asked us to compare America’s behavior during Cold War I (against the Soviet Union) with America’s behavior during Cold War II (against China). I look at that difference and I see a stark contrast — between a nation back in the 1950s that possessed an assumed self-confidence versus a nation today that is even more powerful but has had its easy self-confidence stripped away.

There is much more at the NYT link.

The Sputnik vs. Deep Seek Moment: The Answers

In The Sputnik vs. DeepSeek Moment I pointed out that the US response to Sputnik was fierce competition. Following Sputnik, we increased funding for education, especially math, science and foreign languages, organizations like ARPA were spun up, federal funding for R&D was increased, immigration rules were loosened, foreign talent was attracted and tariff barriers continued to fall. In contrast, the response to what I called the “DeepSeek” moment has been nearly the opposite. Why did Sputnik spark investment while DeepSeek sparks retrenchment? I examine four explanations from the comments and argue that the rise of zero-sum thinking best fits the data.

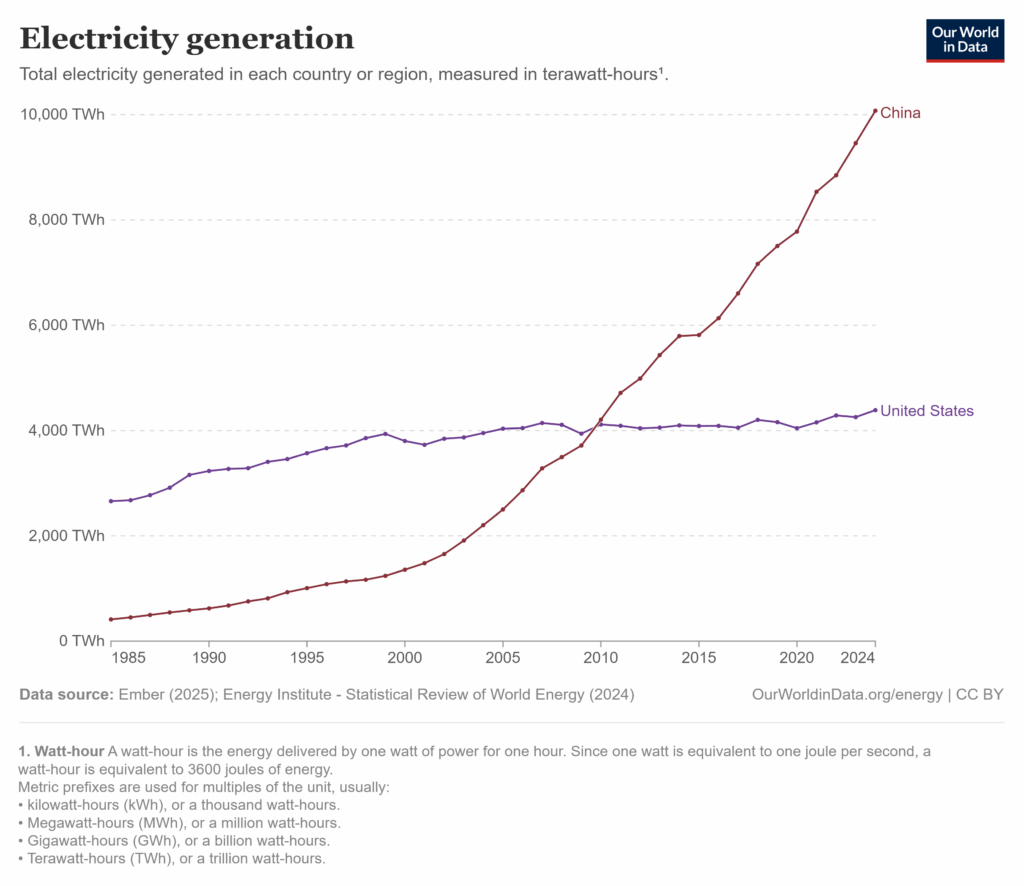

Several comments fixated on DeepSeek itself, dismissing it as neither impressive nor threatening. Perhaps but DeepSeek was merely a symbol for China’s broader rise: the world’s largest exporter, manufacturer, electricity producer, and military by headcount. These critiques missed the point.

Some commenters argued that Sputnik provoked a strong response because it was seen as an existential threat, while DeepSeek—and by extension China—is not. I certainly hope China’s rise isn’t existential, and I’m encouraged that China lacks the Soviet Union’s revolutionary zeal. As I’ve said, a richer China offers benefits to the United States.

But many influential voices do view China as a very serious, even existential, threat—and unlike the USSR, China is economically formidable.

More to the point, perceived existential stakes don’t answer my question. If the threat were greater, would we suddenly liberalize immigration, expand trade, and fund universities? Unlikely. A more plausible scenario is that if the threat were greater, we would restrict harder—more tariffs, less immigration, more internal conflict.

Several commenters, including my colleague Garett Jones, pointed to demographics—especially voter demographics. The median age has risen from 30 in 1950 to 39 in recent years; today’s older, wealthier, more diverse electorate may be more risk-averse and inward-looking. There’s something to this, but it’s not sufficient. Changes in the X variables haven’t been enough to explain the change in response given constant Betas so demography doesn’t push that far but does it even push in the right direction?

Age might correlate with risk-aversion, for example, but the Trump coalition isn’t risk-averse—it’s angry and disruptive, pushing through bold and often rash policy changes.

A related explanation is that the U.S. state has far less fiscal and political slack today than it did in 1957. As I argued in Launching, we’ve become a warfare–welfare state—possibly at the expense of being an innovation state. Fiscal constraints are real, but the deeper issue is changing preferences. It’s not that we want to return to the moon and can’t—it’s that we’ve stopped wanting to go.

In my view, the best explanation for the starkly different responses to the Sputnik and DeepSeek moments is the rise of zero-sum thinking—the belief that one group’s gain must come at another’s expense. Chinoy, Nunn, Sequiera and Stantcheva show that the zero sum mindset has grown markedly in the U.S. and maps directly onto key policy attitudes.

Zero sum thinking fuels support for trade protection: if other countries gain, we must be losing. It drives opposition to immigration: if immigrants benefit, natives must suffer. And it even helps explain hostility toward universities and the desire to cut science funding. For the zero-sum thinker, there’s no such thing as a public good or even a shared national interest—only “us” versus “them.” In this framework, funding top universities isn’t investing in cancer research; it’s enriching elites at everyone else’s expense. Any claim to broader benefit is seen as a smokescreen for redistributing status, power, and money to “them.”

Zero-sum thinking doesn’t just explain the response to China; it’s also amplified by the China threat. (hence in direct opposition to some of the above theories, the people who most push the idea that the China threat is existential are the ones who are most pushing the zero sum response). Davidai and Tepper summarize:

People often exhibit zero-sum beliefs when they feel threatened, such as when they think that their (or their group’s) resources are at risk…Similarly, working under assertive leaders (versus approachable and likeable leaders) causally increases domain-specific zero-sum beliefs about success….. General zero-sum beliefs are more prevalent among people who see social interactions as a competition and among people who possess personality traits associated with high threat susceptibility, such as low agreeableness and high psychopathy, narcissism and Machiavellianism.

Zero-sum thinking can also explain the anger we see in the United States:

At the intrapersonal level, greater endorsement of general zero-sum beliefs is associated with more negative (and less positive) affect, more greed and lower life satisfaction. In addition, people with general zero-sum beliefs tend to be overly cynical, see society as unjust, distrust their fellow citizens and societal institutions, espouse more populist attitudes, and disengage from potentially beneficial interactions.

…Together, these findings suggest a clear association between both types of zero-sum belief and well-being.

Focusing on zero-sum thinking gives us a different perspective on some of the demographic issues. In the United States, for example, the young are more zero-sum thinkers than the old and immigrants tend to be less zero-sum thinkers than natives. The likeliest reason: those who’ve experienced growth understand that everyone can get a larger slice from a growing pie while those who have experienced stagnation conclude that it’s us or them.

The looming danger is thus the zero-sum trap: the more people believe that wealth, status, and well-being are zero-sum, the more they back policies that make the world zero-sum. Restricting trade, blocking immigration, and slashing science funding don’t grow the pie. Zero-sum thinking leads to zero-sum policies, which produce zero-sum outcomes—making the zero sum worldview a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Markets in everything those new service sector jobs

Witchcraft and spellwork have become an online cottage industry. Faced with economic uncertainty and vapid dating apps, some people are putting their beliefs—and disposable income—into love spells, career charms and spirit cleansers.

Etsy, an online marketplace for crafts and vintage, has long been home to psychics and mystics, but the platform has enjoyed new callouts from TikTokers as a destination for witchcraft.

The concept of hiring an Etsy witch hit a fever pitch when influencer Jaz Smith told her TikTok followers that she had paid one to make sure the weather was perfect during her Memorial Day Weekend wedding. The blue skies and warm temperature have inspired TikTok audiences to find Etsy witches of their own. Smith didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Rohit Thawani, a creative director in Los Angeles, said Smith was his inspiration for paying an Etsy witch $8.48 to cast a spell on the New York Knicks ahead of Game 5 of the Eastern Conference finals in May.

Thawani found a witch offering discount codes. Thawani was half-kidding about the transaction but was amazed when the Knicks won. “Maybe there’s something more cosmic out there,” Thawani, 43, said.

Thawani bought a second spell ($21.18) from the Etsy witch for Game 6, but the Knicks lost. He doesn’t rule out the possibility that Indiana Pacers fans “used their devil magic,” he joked.

Magic practitioners sell on Instagram, Shopify and TikTok, but most customers say Etsy is their go-to.

The shop MariahSpells has over 4,000 sales on Etsy and 4.9 stars and sells a permanent protection spell for about $200. Another shop, Spells by Carlton, has over 44,000 sales and lists a “bring your ex lover back” spell for about $7.

Here is more from the WSJ, via the excellent Samir Varma.

Asymmetric economic power?

America’s trading partners have largely failed to retaliate against Donald Trump’s sweeping tariffs, allowing a president taunted for “always chickening out” to raise nearly $50bn in extra customs revenues at little cost.

Four months since Trump fired the opening salvo of his trade war, only China and Canada have dared to hit back at Washington imposing a minimum 10 per cent global tariff, 50 per cent levies on steel and aluminium, and 25 per cent on autos.

At the same time US revenues from customs duties hit a record high of $64bn in the second quarter — $47bn more than over the same period last year, according to data published by the US Treasury on Friday.

China’s retaliatory tariffs on American imports, the most sustained and significant of any country, have not had the same effect, with overall income from custom duties only 1.9 per cent higher in May 2025 than the year before.

Here is more from the FT. To be clear, I do not think this is good. Nonetheless it amazes me how many economists a) reject the “Leviathan” approach to analyzing public choice and U.S. government, b) think “normative nationalism” is fine, c) have expressed partial “trade skepticism” for some while, and d) think our government should raise a lot more revenue, including through consumption taxes…and yet they find this to be about the worst policy they ever have seen.

Some also will tell you that higher inflation is not such a terrible thing, though whether they extend this view to inflation from real shocks is disputable.

With some debatable number of national security exceptions, zero tariffs is the way to go. But you can only get there through broadly libertarian frameworks, not through conventional “mid-establishment” policy analyses.

Britain fact of the day

As the number of Brits on sickness and disability support has rocketed in recent years, so have Motability’s sales. It uses its heft to buy new models in bulk, then leases them to claimants — usually for three years — before selling them on to traders like Samani. That has made it the UK’s leading car-fleet operator, and helped skew the market away from private buyers and sellers.

Get this:

Motability bought one of every five new cars sold in the UK last year. And yet it only exists to serve a very specific type of customer: people claiming mobility benefits.

A surge in the number of people claiming disability benefits has seen the number of Motability customers rise by about 200,000 over the past two years to 815,000.

Not good! The market for new private cars is really so anemic? Here is more from Bloomberg. Sarah Haider, telephone!

p.s. When it comes to disability: “In 2024 the DWP reported that there were 0% of fraudulent claims made.“ Whew…

Finland fact of the day

Nearly half of Finns now identify with the political right, according to a new survey by the Finnish Business and Policy Forum (EVA), marking a record high in the organisation’s annual values and attitudes research.

The 2025 survey found that 49 percent of respondents place themselves on the right of the political spectrum. The proportion identifying with the left stands at 31 percent, while only 19 percent consider themselves centrist. The centre has declined steadily with each round of the survey.

Here is the full story, via Rasheed.

Bari Weiss, Kyla Scanlon, and I on why young people love socialism

Here is the podcast.

Tariff Shenanigans

In our textbook, Tyler and I give an amusing example of how entrepreneurs circumvented U.S. tariffs and quotas on sugar. Sugar could be cheaply imported into Canada and iced tea faced low tariffs when imported from Canada into the U.S., so firms created a high-sugar iced “tea” that was then imported into the US and filtered for its sugar!

Bloomberg reports a similar modern workaround. Delta needs new airplanes but now faces steep tariffs on imported European aircraft. As a result, Delta has been stripping European planes of their engines, importing the engines at low tariff rates, and installing them on older aircraft.