Category: Data Source

Mexico fact of the day

When the news was announced that Mexicans work longer days than anyone else in the world, many people here were too busy to notice.

“Really?” Marcelo Barrales said, “the longest?”

Mexicans work an average of ten hours a day, paid and unpaid labor, even though the country is far from the world’s poorest. Belgians work the least number of hours a day, at seven. It can be argued that these long hours stem in part from the inefficiency of labor in Mexico, but still this should put to rest the cliched notion that in Mexico the work ethic is weak.

Natural Gas

The graph is from Peter Tertzakian who notes:

To put this in perspective, 1,000 Tcf of natural gas contains the equivalent energy to 166 billion barrels of oil – a staggering amount considering that the discovery of 10 billion barrels of conventional oil these days is a rare occurrence, worthy of many headlines…

Estimates of recoverable shale gas have doubled in just the past year and shale gas is only part of the supply with the total being 2,552 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of potential natural gas resources in the U.S. alone. Per unit of electricity, burning natural gas results in significantly fewer carbon dioxide emissions than coal. It is possible, however, that fracking may leak more methane to the atmosphere so the net climate benefit is unclear, at least given current methods of development.

Hat tip: Paul Kedrosky.

The Great Stagnation, in agriculture

Overall, it is neglected knowledge just how much the “Green Revolution” has slowed down since the 1990s. In Africa, measured heights have stagnated or declined in recent times. Robert Paarlberg’s Starved for Science: How Biotechnology is Being Kept Out of Africa is an excellent book on its title topic and more generally on falling TFP in global agriculture.

On other commodities, there are further charts and graphs (on both sides of the debate) here. The article is overwrought but worth the read, as it shows how far we are currently from the world of Julian Simon.

Sentences to make you angry (or not)

In a recent paper, James Lindgren of Northwestern reports:

…compared to anti-redistributionists, strong redistributionists have about two to three times higher odds of reporting that in the prior seven days they were angry, mad at someone, outraged, sad, lonely, and had trouble shaking the blues. Similarly, anti-redistributionists had about two to four times higher odds of reporting being happy or at ease. Not only do redistributionists report more anger, but they report that their anger lasts longer. When asked about the last time they were angry, strong redistributionists were more than twice as likely as strong opponents of leveling to admit that they responded to their anger by plotting revenge. Last, both redistributionists and anti-capitalists expressed lower overall happiness, less happy marriages, and lower satisfaction with their financial situations and with their jobs or housework.

Further, in the 2002 and 2004 General Social Surveys anti-redistributionists were generally more likely to report altruistic behavior. In particular, those who opposed more government redistribution of income were much more likely to donate money to charities, religious organizations, and political candidates. The one sort of altruistic behavior that the redistributionists were more likely to engage in was giving money to a homeless person on the street.

This is much more to this paper. For instance, at the U.S. national level, racists tend to be pro-income redistribution on net. Anti-capitalist attitudes are associated with higher levels of intolerance. I thank an MR reader for the pointer, I am sorry that I have lost the identifying email.

Bryan Caplan, prophet of his time

From today’s NYT:

…not all parents are made wretched by their offspring. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research in Rostock, Germany, and the University of Pennsylvania found that people over the age of 40 [my link] are happier with children than without.

To arrive at this conclusion, the demographers Mikko Myrskyla and Rachel Margolis crunched data from the World Values Surveys, looking at self-reported levels of happiness among more than 200,000 respondents from 86 countries.

They studied how individual factors such as age, sex, income and health status affected happiness as well as how the respondents’ institutional and cultural context came into play — whether they lived in countries with a social democratic, conservative or developing regime. This led to some interesting off-shoot conclusions like this one: people in former socialist countries show a strong positive relationship between happiness and child-raising, with parents of three in those countries happiest of all.

But the most striking findings revolved around parenthood and age. Whether it is a function of exhaustion, bickering over diapers or something inherently unpleasant about raising little children, the data doesn’t say, but parents under 30 are decidedly less happy than their child-free peers. Then, once parents hit 40, the relationship reverses and people with children are cheerier than those without.

The more, the merrier, too — at least for older parents. For people under 30, happiness declines with each additional child. Young parents of two are unhappier than young parents with one, and young parents of one child are unhappier than young people with no children. But with parents between the ages of 40 and 50, the number of children has no impact. And after 50, each child brings more joy.

The source paper is here. You can, and should, buy Bryan’s new book here.

Haiti fact of the day

At the time the United States intervened in Haiti in 1994, the U.S. defense budget of $288 billion was 20 times the entire gross domestic product of Haiti.

[TC: And yet we still did not quite achieve our war aims.] That is from the new and interesting book by Sarah E. Kreps, Coalitions of Convenience: United States Military Interventions After the Cold War.

Here are music videos by Sweet Micky, the new President of Haiti. I’ve seen him in concert three times and it was always enjoyable.

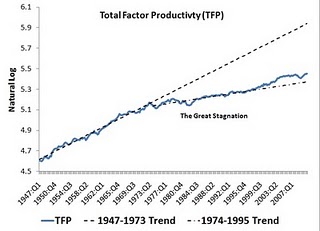

Total Factor Productivity

Dennis is Not More Likely to be a Dentist

Pelham, Mirenberg and Jones (2002) found that the names Jerry, Dennis and Walter were the 39th, 40th, and 41st most frequent male names in the 1990 census (moreover the absolute frequency of (Jerry+Walter)/2 was almost identical to that of Dennis). But in a nationwide search they found 482 dentists named Dennis but just 257 named Walter, and 270 named Jerry, a highly statistical significant difference. Hence the meme was born, “Dennis is more like to be a Dentist.”

The expected number of dentists named Dennis, however, depends not on the frequency of Dennis in the 1990 Census but on the entire stock of people named Dennis over the past ~70 years and similarly for Walter and Jerry. If, for example, no one was ever named Jerry prior to 1989 but in 1990 the name skyrocketed to prominence following the appearance of Seinfeld then there would be no dentists named Jerry despite Jerry being a popular name in the 1990 census.

Following this logic, Uri Simonsohn proposes that instead of comparing the number of dentists named Dennis to those named Jerry or Walter we compare the number of dentists named Dennis to the number of lawyers named Dennis. Making this comparison, Simonsohn finds that Dennis’s are just as overrepresented among lawyers as among dentists, thus the Dennis is a dentist finding is most likely due to a spurious cohort effect.

In addition, to testing the name-profession link Simonsohn reexamines many of the classics of the implicit egoism literature and finds many of them (not all and he does not challenge the experimental results) wanting. Virginia is not more likely to move to Virginia, for example. The Simonsohn paper is impressive and a great resource for anyone wanting to teach the difficulties of doing causal statistical research.

The Spence and Hlatshwayo paper is now on-line

The Browser informs us (pdf behind that link), bravo to them, here is the abstract:

This paper examines the evolving structure of the American economy, specifically, the trends in employment, value added, and value added per employee from 1990 to 2008. These trends are closely connected with complementary trends in the size and structure of the global economy, particularly in the major emerging economies. Employing historical time series data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Bureau of Economic Analysis, U.S. industries are separated into internationally tradable and nontradable components, allowing for employment and value-added trends at both the industry and the aggregate level to be examined. Value added grew across the economy, but almost all of the incremental employment increase of 27.3 million jobs was on the nontradable side. On the nontradable side, government and health care are the largest employers and provided the largest increments (an additional 10.4 million jobs) over the past two decades. There are obvious questions about whether those trends can continue; without fast job creation in the nontradable sector, the United States would already have faced a major employment challenge. The trends in value added per employee are consistent with the adverse movements in the distribution of U.S. income over the past twenty years, particularly the subdued income growth in the middle of the income range. The tradable side of the economy is shifting up the value-added chain with lower and middle components of these chains moving abroad, especially to the rapidly growing emerging markets. The latter themselves are moving rapidly up the value-added chains, and higher-paying jobs may therefore leave the United States, following the migration pattern of lower-paying ones. The evolution of the U.S. economy supports the notion of there being a long-term structural challenge with respect to the quantity and quality of employment opportunities in the United States. A related set of challenges concerns the income distribution; almost all incremental employment has occurred in the nontradable sector, which has experienced much slower growth in value added per employee. Because that number is highly correlated with income, it goes a long way to explain the stagnation of wages across large segments of the workforce.

A few points:

1. p.10 offers interesting remarks about China, namely that China is approaching a “middle income range” where economic growth commonly slows.

2. This paper has some of the best disaggregated information for those who are not convinced by simpler calculations of median income growth slowdown.

3. pp.33-34 offer a good summary of results and also a good explanation of current structural unemployment which does not fall prey to the usual criticisms offered by the blogosphere Keynesians, who on this issue remain behind the curve.

4. p.37 has good, short remarks on Germany and (now switching to my words) why it is wrong to dismiss their recent successes.

5. The co-author, Sandile Hlatshwayo, is at the Stern School of Business, NYU. He, she or a namesake is taking a honeymoon poll.

Overall, this is one of the most important papers of the year and perhaps the most important paper so far on “economic malaise” issues. It is also a useful corrective to the political conspiracy theories of changes in the income distribution (if you are wondering, Spence at least would not count as a right-winger, I cannot speak to Hlatshwayo).

As for The Browser, it is better than I ever expected a web site to be.

Addendum: Arnold Kling comments.

Unemployment, Recessions and Barter: A Test

Nick Rowe explains that the essence of New Keynesian/Monetarist theories of recessions is the excess demand for money (Paul Krugman’s classic babysitting coop story has the same lesson). Here’s Rowe:

The unemployed hairdresser wants her nails done. The unemployed manicurist wants a massage. The unemployed masseuse wants a haircut. If a 3-way barter deal were easy to arrange, they would do it, and would not be unemployed. There is a mutually advantageous exchange that is not happening. Keynesian unemployment assumes a short-run equilibrium with haircuts, massages, and manicures lying on the sidewalk going to waste. Why don’t they pick them up? It’s not that the unemployed don’t know where to buy what they want to buy.

If barter were easy, this couldn’t happen. All three would agree to the mutually-improving 3-way barter deal. Even sticky prices couldn’t stop this happening. If all three women have set their prices 10% too high, their relative prices are still exactly right for the barter deal. Each sells her overpriced services in exchange for the other’s overpriced services….

The unemployed hairdresser is more than willing to give up her labour in exchange for a manicure, at the set prices, but is not willing to give up her money in exchange for a manicure. Same for the other two unemployed women. That’s why they are unemployed. They won’t spend their money.

Keynesian unemployment makes sense in a monetary exchange economy…it makes no sense whatsoever in a barter economy, or where money is inessential.

Rowe’s explanation put me in mind of a test. Barter is a solution to Keynesian unemployment but not to “RBC unemployment” which, since it is based on real factors, would also occur in a barter economy. So does barter increase during recessions?

There was a huge increase in barter and exchange associations during the Great Depression with hundreds of spontaneously formed groups across the country such as California’s Unemployed Exchange Association (U.X.A.). These barter groups covered perhaps as many as a million workers at their peak.

In addition, I include with barter the growth of alternative currencies or local currencies such as Ithaca Hours or LETS systems. The monetization of non-traditional assets can alleviate demand shocks which is one reason why it’s good to have flexibility in the definition of and free entry into the field of money (a theme taken up by Cowen and Kroszner in Explorations in New Monetary Economics and also in the free banking literature.)

During the Great Depression there was a marked increase in alternative currencies or scrip, now called depression scrip. In fact, Irving Fisher wrote a now forgotten book called Stamp Scrip. Consider this passage and note how similar it is to Nick’s explanation:

If proof were needed that overproduction is not the cause of the depression, barter is the proof – or some of the proof. It shows goods not over-produced but dead-locked for want of a circulating transfer-belt called “money.”

Many a dealer sits down in puzzled exasperation, as he sees about him a market wanting his goods, and well stocked with other goods which he wants and with able-bodied and willing workers, but without work and therefore without buying power. Says A, “I could use some of B’s goods; but I have no cash to pay for them until someone with cash walks in here!” Says B, “I could buy some of C’s goods, but I’ve no cash to do it with till someone with cash walks in here.” Says the job hunter, “I’d gladly take my wages in trade if I could work them out with A and B and C who among them sell the entire range of what my family must eat and wear and burn for fuel – but neither A nor B nor C has need of me – much less could the three of them divide me up.” Then D comes on the scene, and says, “I could use that man! – if he’d really take his pay in trade; but he says he can’t play a trombone and that’s all I’ve got for him.”

“Very well,” cries Chic or Marie, “A’s boy is looking for a trombone and that solves the whole problem, and solves it without the use of a dollar.

In the real life of the twentieth century, the handicaps to barter on a large scale are practically insurmountable….

Therefore Chic or somebody organizes an Exchange Association… in the real life of this depression, and culminating apparently in 1933, precisely what I have just described has been taking place.

What about today? Unfortunately, the IRS doesn’t keep statistics on barter (although barterers are supposed to report the value of barter exchanges). Google Trends shows an increase in searches for barter in 2008-2009 but the increase is small. Some reports say that barter is up but these are isolated, I don’t see the systematic increase we saw during the Great Depression. I find this somewhat surprising as the internet and barter algorithms have made barter easier.

In terms of alternative currencies, the best data that I can find shows that the growth of alternative currencies in the United States is small, sporadic and not obviously increasing with the recession. (Alternative currencies are better known in Germany and Argentina perhaps because of the lingering influence of Heinrich Rittershausen and Silvio Gesell).

In sum, the increase in barter and scrip during the Great Depression is supportive of the excess demand for cash explanation of that recession, even if these movements didn’t grow large enough, fast enough to solve the Great Depression. Today there seems to be less interest in barter and alternative currencies than expected, or at least than I expected, given an AD shock and the size of this recession. I don’t draw strong conclusions from this but look forward to further research on unemployment, recessions and barter.

Givewell on Giving to Japan

I agree with this advice from Givewell the most analytically tough of the charity ratings agencies.

* Those affected have requested very little, limited aid. Aid being offered far exceeds aid being requested.

* Charities are aggressively soliciting donations, often in ways we feel are misleading.

* Any donation you make will probably be used (a) by the charity you give it to, for activities in a different country; (b) for non-disaster-relief-and-recovery efforts in Japan.

* If you’re looking to pursue (a) and help people in need all over the world, we recommend giving to the best charity you can, rather than basing your giving on who is appealing to you most aggressively with images and language regarding Japan.

* If you prefer (b), a gift to the Japanese Red Cross seems reasonable.Overall, though, a gift to Doctors Without Borders seems to us like the best way to effectively “respond to this disaster”. We feel they are a leader in transparency, honesty and integrity in relief organizations, and the fact that they’re not soliciting funds for Japan is a testament to this. Rewarding Doctors Without Borders is a move toward improving incentives and improving disaster relief in general.

Thoughts about labor markets

Today, the number of layoffs and discharges is very low — in fact, layoffs are at their lowest level since the Labor Department began collecting this data in 2000. Today’s problem instead is the very slow pace of job creation.

Yet unemployment remains high. File under “increasing polarization of labor market outcomes.”

Here is Steve Pearlstein channeling A. Michael Spence:

…what ails the U.S. economy is primarily a structural problem, not a cyclical one that can be effectively dealt with through the magic of short-term Keynesian stimulus.

Or let’s consider David Leonhardt’s very good piece on the labor market:

Lawrence Katz, a Harvard labor economist, calls the full [labor market] picture “genuinely puzzling.”

That is Larry Katz, who was chief economist at the Department of Labor under Clinton and who is arguably the most knowledgeable labor economist in the world. Larry Katz, who is renowned for how many literatures he holds at his fingertips. (Here are some papers by Larry Katz, including a good, short piece on unemployment in the great recession.) Larry Katz, who wrote the most effective critique of the Lilien “sectoral shift” hypothesis. Larry Katz, force of nature.

I am not asking you to agree with Spence or Katz, only to keep them in mind. What is striking about the current generation of popular Keynesian models is how little effort they make to integrate cyclical and structural phenomena. This is very much like some of the original Keynesian models of the 1930s, but it is an out of date approach and it will lead to excess optimism about the ability of fiscal stimulus to set things right.

America tornado fact of the day

“People are 10 times more likely to die in a mobile home than if the same tornado hit a regular home,” says book co-author Kevin Simmons, an economist at Austin College in Sherman, Texas.

Simmons says mobile homes constitute only 7% of the USA’s housing stock, but his research found that 43% of all tornado deaths are to people in mobile homes, which can be no match for a tornado’s violent winds, clocked as high as 300 mph.

Here is more, and the data are taken from this new book by Simmons and Daniel Sutter, on the economics of tornadoes, the book’s home page is here.

*The Way it Worked*

The author is Gordon C. Bjork and the subtitle is Structural Change and the Slowdown of U.S. Economic Growth. I recommend this not-so-well known book, first published in 1999, very highly. Among its other merits, it traces how much of the productivity slowdown results from the switch of the U.S. economy into lower-growing sectors. Excerpt:

Thus, if the 1950s structure of relative output levels and employment were combined with the intra-sector growth rates of the decade ending in 1990, the aggregate intra-sector growth rate would have been 19 percent as opposed to the 13.2 percent it actually was in the decade ending 1990. If the slow-growth decade of the 1980s had had the same output structure as the high-growth 1950s, it would have had higher growth rates than the high-growth 1950s. Conversely, if the 1990 structure had been in effect in the 1950s, the intra-sectoral growth rate for the decade would have been only 11 percent, rather than its actual 17 percent. These two examples of the effect of output structure on average growth rates illustrate the importance of structural change in determining aggregate rates of growth in per worker output by changing the relative size of sectors.

The male median wage picture is worse than we had thought

David Leonhardt has the scoop, here is an excerpt from the quoted Michael Greenstone:

The red line is the usual picture of median earnings for full-time men. The problem with this line is that the percentage of men working over time has been declining over time. This attrition or dropping out of the labor force is not random, though, as the decline in full-time work it is disproportionately concentrated among low-skill men. This means that the red line is being propped up by the fact that it is increasingly comprised of higher skilled men.

One sensible correction for this is to calculate the median wage for all men (not just the full-time workers). This is the blue line in the below graph.

Why is this important? The full-time sample (red line) suggests that median wages have been stagnant since 1969. The blue line or full sample of men (which accounts for reduced labor force participation) suggests that median wages have declined by 32% or $15,000 (in constant dollars). [emphasis added by TC]