Category: Economics

Why Don’t Women Patent?

In Why Don’t Women Patent?, a recent NBER paper, Jennifer Hunt et al. present a stark fact: Only 5.5% of the holders of commercialized patents are women. One might think that this is explained by the relative lack of women with science and engineering degrees but Hunt et al. find that “women with such a degree are scarcely more likely to patent than women without.” Instead, most of the difference is “accounted for by differences among those with a science or engineering degree” especially the fact that women are underrepresented in patent-intensive fields such as electrical and mechanical engineering and in development and design.

Predictably, the authors do not ask why women might self-select into non patent-intensive fields, perhaps because this would require at least a discussion of politically incorrect questions. The failure to investigate these questions leads to some dubious conclusions, notably:

Closing the [gender] gap among S&E degree holders would increase commercialized patents by 24% and GDP per capita by

2.7%.

Right; and since only 10% of construction workers are women, closing the gender gap would result in many more houses. In the case of construction, my suspicion is that gender equality would reduce not increase the amount of construction. In the case of patents, I am not sure what would happen, indeed the point is that without a much better understanding of what causes differences in patent proclivities one shouldn’t jump to conclusions.

The quick jump from patents to innovation is also unwarranted–there is very little evidence that patents increase innovation. Moreover, most innovations are not patented. If we measured innovation more closely it wouldn’t surprise me if women accounted for a larger share of innovation than they do of patents.

By the way, both my wife and I are working to rectifiy these statistics, she has half-a-dozen patents and I have none.

Addendum: Freakonomics/Marketplace has a podcast on this topic.

Bank lending in China

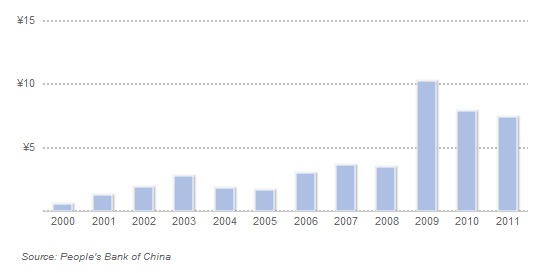

With caveats about the data, yes, but still this is striking:

That is from Christopher Balding’s Asia/China blog, the post is here. It is entitled “Why I am Concerned About the Chinese Economy in One Picture.” If you would prefer the words:

From 2008 to 2009 new local currency loans rose from 3.48 trillion rmb to 10.32 trillion according to the PBOC for an annualized increase of nearly 300%.

I do not know if those who praised the Chinese in 2009 for their aggressive stimulus program are having second thoughts, or fearing that the stimulus simply postponed — and intensified — a much-needed adjustment.

Sentences which were not expected

“I can’t see why we should be printing bank notes at all anymore,” says Bjoern Ulvaeus, former member of 1970’s pop group ABBA, and a vocal proponent for a world without cash.

That is from The Washington Post, hat tip to Brad Plumer. The article is interesting throughout, for instance:

The Swedish Bankers’ Association says the shrinkage of the cash economy is already making an impact in crime statistics.

The number of bank robberies in Sweden plunged from 110 in 2008 to 16 in 2011 — the lowest level since it started keeping records 30 years ago. It says robberies of security transports are also down.

“Less cash in circulation makes things safer, both for the staff that handle cash, but also of course for the public,” says Par Karlsson, a security expert at the organization.

The prevalence of electronic transactions — and the digital trail they generate — also helps explain why Sweden has less of a problem with graft than countries with a stronger cash culture, such as Italy or Greece, says economics professor Friedrich Schneider of the Johannes Kepler University in Austria.

“If people use more cards, they are less involved in shadow economy activities,” says Schneider, an expert on underground economies.

More on the time-dependence of fiscal policy

Chris Reicher has a new paper (pdf) and the abstract is here:

This paper documents the systematic response of postwar U.S. fiscal policy to fiscal imbalances and the business cycle using a multivariate Fiscal Taylor Rule. Adjustments to taxes and purchases both account for a large portion of the fiscal response to debt, while authorities seem reluctant to adjust transfers. As expected, taxes are highly procyclical; purchases are acyclical; and transfers are countercyclical. Neither pattern has changed much over time, except that adjustment happens more slowly after 1981 than before 1980. The role of adjustments to purchases in stabilizing the debt indicates that the recent discussion about spending reversals is highly relevant.

The gated, published version is here. Chris writes me in an email:

Germany uses a similar mix of spending restraint vs. tax increases as the United States in order to consolidate its fiscal position over time. My 2012 article basically corroborates Bohn’s results using different techniques for the postwar period. I have a set of unpublished estimates which indicates the same thing for Germany and a number of other countries–adjustments to real spending and taxes both account for large portions of fiscal authorities’ endogenous response to debt.

Chris points me to a further paper on the topic, forthcoming in ReStat.

A new and revised and more pessimistic view of U.S. manufacturing

Between 2000 and 2010, manufacturing output of computer and electronic products rose at a remarkable rate of almost 18 percent per year.

Over the same period, output in the rest of U.S. manufacturing remained roughly flat, according to Bureau of Economic Analysis figures tallied by Houseman. That’s a dismal showing for a decade.

It is only when computer and electronic products are included that overall manufacturing output registers the impressive increases. Though it represents 15 percent or less of manufacturing output, the sector’s strong growth makes the rest of U.S. manufacturing seem much more robust than it really is.

At the same time:

…much of the nation’s production of computers and electronics has moved overseas. The number of consumer electronics shipped from U.S. factories dipped about 70 percent between 2000 and 2010, according to the Census Bureau’s Current Industrial Report.

And:

…at least some of the productivity gains shown in U.S. computer manufacturing reflect the increasing power and decreasing prices that come with innovation. When a computer chip doubles in efficiency, that can turn up in a doubling of output and productivity in computer manufacturing. But that is not what is ordinarily thought of as manufacturing efficiency.

The article is here. It also makes the point that a lot of measure manufacturing productivity gains are actually the result of offshoring, not actual higher productivity in U.S. factories; “This bias may have accounted for as much as half of the growth of U.S. manufacturing output from 1997 to 2007, excluding computers and electronics manufacturing, Houseman and her co-authors have estimated.”

I thank Brent Depperschmidt for the pointer.

The quest for microfoundations

There has been recent debate in the blogosphere about what we learn from demanding microfoundations for macro results. I am a firm believer in microfoundations, while recognizing the abuses to which the concept has been put.

Via Mark Thoma, enter Robert Hall and his latest paper (pdf), here is the abstract:

The financial crisis of late 2008 shifted household expenditure downward, as financial institutions tightened lending standards and required repayment of outstanding consumer loans. The crisis also raised financial frictions by depleting the equity capital of financial institutions. The result was a severe reduction in business and residential investment expenditure. The zero bound on the interest rate worsened the adverse effects of these developments by limiting the corrective response of monetary policy. In a straightforward and comprehensible macro model, I measure the two financial driving forces by matching the actual and forecasted movements of two key variables, the unemployment rate and the investment/GDP ratio. I then use the model to describe a counterfactual economy over the period 2009 through 2020 in which the same increase in financial frictions occurred but no household deleveraging took place. The comparison of the counterfactual and actual economies reveals the separate effects of the two financial driving forces. Deleveraging had an important but transitory role immediately after the crisis, while high financial frictions account for the long period of high unemployment, depressed GDP, and subnormal investment.

Maybe you don’t agree with Hall (I am of mixed mind), but he gives us a systematic framework for analyzing the depth and length of the recent recession, noting that it is microfoundations but not strict DSGE because he wishes to create more space for changes in basic structural parameters.

I have three observations: a) such a paper would not have been possible without a microfoundations approach, b) Hall finds a strong role for intermediation, which is a favorite topic of the microfoundations advocates and a feature lacking in IS-LM models, and c) his methods suggest some weaknesses in the recent stress on deleveraging as the continuing plague, again noting this is a framework for discussion rather than the final answer.

The microfoundations approach proves its value virtually every day.

Timothy Noah’s *The Great Divergence*

The subtitle is America’s Growing Inequality Crisis and What We Can Do About It. His policy conclusions are:

1. Soak the rich

2. Fatten government payrolls

3. Import more skilled labor

4. Universalize preschool

5. Impose price controls on colleges and universities

6. Reregulate Wall Street

7. Elect Democratic Presidents

8. Revive the labor movement

This book is well-written and it is a useful survey of left-democrat points of view on the problem. I do not think most of these recommendations will much limit inequality (though they may have other virtues), but my main wish is that he had offered some additional possible solutions. #1 on my list is “more innovations which benefit virtually everybody,” which is how the last great equalization (1870-1970 or so) came about. Parts of his list, such as #3, get at this obliquely but it should be front and center of the entire book. Let’s debate how we can make that happen. If there were a new invention as important as the toilet, shareholders would not and could not appropriate most of the gains. “Deregulate housing” and “deregulate medical care” also deserve a ponder, as does “abolish occupational licensing” and “subsidize basic science.” That global inequality has fallen radically is understood and recognized but not emphasized. It is culturally beyond the pale — on the left at least — to write “encourage conversions to Mormonism” but as a recommendation it is right on the mark. This book needs more which is culturally beyond the pale. How about “run some of the bad schools with lots of discipline, more like the KIPP academy?”

Lunch with Scott Sumner (and others) at China Star

How is that for self-recommending? Here in a short paragraph is my current take on where Ben Bernanke would differ from Scott. As the shadow banking system was imploding in 2008, due to a downward revaluation of collateral, nominal gdp stabilization would have required that the Fed resort to the medium of currency printing on a very large scale. Scott favors such a move. Bernanke would worry that the collapse of (some) intermediation would mean you get most of the output losses anyway, while the printing of currency would create subsequent problems with management of expectations, relative sectoral shocks (currency is only a partial substitute for credit), and medium-term adjustment once the smoke has cleared, not to mention political relations with Congress and interest groups within the Fed system itself. Therefore Bernanke didn’t want to do it, even though in principle he likes to see nominal gdp stabilized, and has written and said as such.

I am not suggesting that Scott agrees with this perspective.

Temporary vs. permanent increases in government spending

Not long ago Paul Krugman wrote:

To a first approximation, in other words, the effect of current fiscal policy — whether stimulus or austerity — an [on?] the actions of future governments is zero.

He makes further points at the link, although there is not a citation to the literature. I thought we should look at the evidence a little more closely. Some of it contradicts Krugman as read literally, though it is not all bad news for his larger point.

Here is an abstract from Brian Goff:

In spite of Peacock and Wiseman’s 1961 NBER study demonstrating the “displacement effect”, simplistic theoretical and empirical distinctions between temporary and permanent spending are common. In this paper, impulse response functions from ARMA models as well as Cochrane’s non-parametric method support Peacock and Wiseman’s conclusion by showing 1) government spending in the aggregate displays strong persistence to temporary shocks, 2) simple decomposition methods intended to yield a “temporary” spending series have a weak statistical foundation, and 3) persistence in spending has increased during this century. Also, as a basic “fact” of government spending behavior, the displacement effect lends support to interest group and bureaucracy models of government spending growth.

There is persistence to spending, although this study does not create a category for stimulus spending per se, however that concept might be defined. The work of Robert Higgs also provides a clear look at ratchet effects on government spending, control, and regulation, although Higgs focuses on war rather than spending. State governments also seem to exhibit a ratchet effect, whereby good times bring about permanently higher budgetary demands, if only through endowment effects, lock-in, and status quo bias.

That said, the federal debt/gdp ratio seems to show mean reversion, as does the measure of primary surplus. That would mean that fiscally troubled situations are followed by improvements, though not necessarily from spending decreases. In fact there has been considerable reliance on a “growth dividend.” And here is Henning Bohn from the QJE:

How do governments react to the accumulation of debt? Do they take corrective measures, or do they let the debt grow? Whereas standard time series tests cannot reject a unit root in the U. S. debt-GDP ratio, this paper provides evidence of corrective action: the U. S. primary surplus is an increasing function of the debt-GDP ratio. The debt-GDP ratio displays mean-reversion if one controls for war-time spending and for cyclical fluctuations. The positive response of the primary surplus to changes in debt also shows that U. S. fiscal policy is satisfying an intertemporal budget constraint.

In other words, we make up for first-temporary-then-permanent spending boosts by a mix of growth and higher taxes. Krugman might well be happy with that scenario, but the data do show intertemporal interdependence for budgetary decisions, with a mix of persistence on one variable (spending) and mean-reversion on another (debt-gdp ratio). And if you think a lot of government spending is inefficient, you should still be troubled by apparently “temporary” spending bursts.

As with much of macroeconomics, I would apply a good dose of agnosticism to these results (noting that agnosticism is not the same as assuming zero effect), but still the correlations are consistent with my intuitions more generally.

Top marginal tax rates, 1958 vs. 2009

That is another excellent post from Timothy Taylor. Excerpt:

It’s interesting to note that the share of income tax revenue collected by those in the top brackets for 2009–that is, the 29-35% category, is larger than the rate collected by all marginal tax brackets above 29% back in the 1960s.

And:

Raising tax rates on those with the highest incomes would raise significant funds, but nowhere near enough to solve America’s fiscal woes. Baneman and Nunns offer this rough illustrative estimate: “If taxable income in the top bracket in 2007 had been taxed at an average rate of 49 percent, income tax liabilities (before credits) would have been $78 billion (6.7 percent of total pre-credit liabilities) higher, taking into account likely taxpayer behavioral responses to the rate increase.” The behavioral response they assume is that every 10% rise in tax rates causes taxable income to fall by 2.5%.

And this zinger:

One could also use the example of 1959 to argue that many more taxpayers in the broad range of lower- and middle-incomes should face marginal federal tax rates in the range of 16-28%.

I do not favor such a shift, yet somehow that is a neglected comparison.

Innovations>Patents

AEI held a session on patents and patent reform building off Launching the Innovation Renaissance. I opened and Judge Paul Michel, Chief Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (retired), James DeLong of the Convergence Law Institute and Michael Abramowicz of George Washington University School of Law all offered comments.

Here is one brief bit from my talk. You can find the whole thing here.

Parking spots as price controls

But not everywhere:

San Francisco is trying to shorten the hunt with an ambitious experiment that aims to make sure that there is always at least one empty parking spot available on every block that has meters. The program, which uses new technology and the law of supply and demand, raises the price of parking on the city’s most crowded blocks and lowers it on its emptiest blocks. While the new prices are still being phased in — the most expensive spots have risen to $4.50 an hour, but could reach $6 — preliminary data suggests that the change may be having a positive effect in some areas.

There is much more here.

Pop Bonds

Pay on Performance Bonds incentivize private-sector creativity in the performance of public goals. One of the first Pop bonds (also called social improvement or social impact bonds, SIBs) was pioneered by the British government and the UK group Social Finance. The UK Pop bond is designed to reduce prisoner re-conviction rates. Social Finance raised about $8 million from investors to fund a variety of programs for released prisoners, helping them to find work, stay off alcohol and drugs, reintegrate with society and so forth. The programs are managed by a group of non-profits. The UK government has agreed to pay the investors a return but only if reconviction rates are 7.5% less than those of a control group. If reconviction rates fall below the target level, the investors will earn a good rate of return, 7.5-13%, depending on how far rates fall below the control, but they could also lose everything if rates do not fall. The Pop bond issued in 2010 and appears to be going well although no (potential) bond payments are scheduled until 2014.

A Pop bond puts little risk on governments, who pay nothing if the program does not work but who save money if the program does work. With less at risk government should be willing to experiment more and try new approaches to problems. By contracting out, the government also eliminates a public bureaucracy resistant to change. Most importantly, a Pop bond encourages creativity and innovation in social programs. Investors in a Pop bond have an incentive to monitor the groups implementing the programs and to ensure that they choose the very best, most cost-effective programs. The better the program works, the more the investors earn. If Pop bonds expand it may even pay investors to undertake their own experiments to see how best to maximize their returns.

For Pop bonds to work it is critical that outcomes be measured and marked to an appropriate, randomized, control group. If not carefully monitored, the private sector will also excel at innovative and creative gaming at the public expense (see the comments for some suggestions).

More Pop bonds are being planned in the UK and the idea is also catching on in the United States. The Department of Justice and the Department of Labor both have pilot programs in the works and Massachusetts has issued a request for proposals. By the way, Pop bonds are said to be a new idea but the U.S. bounty hunter and bail bond system which works very well is a clear precursor as is the system of privateering.

Pop bonds have the potential to produce public goods with private innovation; they are an idea worth watching.

Price discrimination for higher ed *classes*

Faced with deep funding cuts and strong student demand, Santa Monica College is pursuing a plan to offer a selection of higher-cost classes to students who need them, provoking protests from some who question the fairness of such a two-tiered education system.

Under the plan, approved by the governing board and believed to be the first of its kind in the nation, the two-year college would create a nonprofit foundation to offer such in-demand classes as English and math at a cost of about $200 per unit. Currently, fees are $36 per unit, set by the Legislature for California community college students. That fee will rise to $46 this summer.

The classes would be offered as soon as the upcoming summer and winter sessions; and, if successful, the program could expand to the entire academic year. The mechanics of the program are still being worked out, but generally the higher-cost classes would become available after state-funded classes fill up. The winter session may offer only the higher-cost classes, officials said.

That is some premium for reading and writing! The naive might have thought that would have been guaranteed. The story is here and for the pointer I thank Robert Tagorda.

Model this (the Goldman guy)

Everyone is talking about the Goldman guy who quit, he wrote this (reactions here):

I truly believe that this decline in the firm’s moral fiber represents the single most serious threat to its long-run survival. It astounds me how little senior management gets a basic truth: If clients don’t trust you they will eventually stop doing business with you. It doesn’t matter how smart you are.

Without clients you will not make money. In fact, you will not exist. Weed out the morally bankrupt people, no matter how much money they make for the firm. And get the culture right again, so people want to work here for the right reasons.

This strikes me as economically naive. Is it at least possible that the culture at Goldman has changed (I am not myself committing to any assessment here of GS) because profit maximization dictates such a shift? What are a few possible models?

1. Income from trading has risen in importance, relative to income from clients, and if you can do well trading you will make money, whether or not you are a jerk.

2. Greater competitiveness lowers levels of service quality for efficiency wage-like reasons. GS can no longer play the role of high mark-up, precommit to high-quality, monopolist.

3. We have moved to the “used car” equilibrium. You know they are screwing you over, or trying to, but leaving for the guy next door simply replicates the same basic incentives so you stay put and fight back best you can.

4. The current interest rate spread means they don’t have to try too hard.

Anything else? Those are possible mechanisms, not factual claims about the world. In any case, I am suspicious of his impulse to blame it all on a sudden shift in the moral propensities of the people he was working with.