Category: Economics

What is the real source of the medical adverse selection problem?

Ray Fisman reports on the job market paper of Nathaniel Hendren, an MIT student on the job market this year. Here is an excerpt from Fisman’s piece:

…sufferers of heart disease and cancer have greater self-knowledge than healthy people in terms of what their likely medical care costs will be. The market for insurance unravels, in Hendren’s model, when patients have a clear view of their future health care costs and people who anticipate lower-cost futures self-select out of insurance coverage.

It’s not about knowing more about your state of health, it is about knowing more about how costly your treatment will be.

Walking Fast and Slow

In a famous paper psychologist John Bargh and collaborators gave students at NYU a test very similar to that described by Malcolm Gladwell in Blink:

In front of you is a sheet of paper with a list of five-word sets. I want you to make a grammatical four-word sentence as quickly as possible out of each set. It’s called a scrambled-sentence test. Ready?

- him was worried she always

- are from Florida oranges temperature

- ball the throw toss silently

- shoes give replace old the

- he observes occasionally people watches

- be will sweat lonely they

- sky the seamless gray is

- should not withdraw forgetful we

- us bingo sing play let

- sunlight makes temperature wrinkle raisins

The students were then sent to do another test in an office down the hall. Unbeknownst to them, walking the hall was the real experiment. Scattered in the sentences above are words like “worried,” “Florida,” “old,” “lonely,” “gray,” “bingo,” and “wrinkle.” Bargh reported that students who had been primed with these words took significantly longer to walk down the hall than those not primed with the “old” words.

In the original study there were only 60 participants and the subjects were timed with a stopwatch. A new paper doubles the sample size and uses more accurate infrared sensors. You will probably not be surprised to learn that the new paper fails to replicate the priming effect. As we know from Why Most Published Research Findings are False (also here), failure to replicate is common, especially when sample sizes are small. I haven’t yet described the real surprise, however.

The authors of the new paper, Doyen et al., then took the experiment meta; they ran the experiment again but this time they told half the people supposedly “running” the experiment that they expected the participants to walk slower and the other half they told that they expected the participants to walk faster. (A confederate provided evidence for this effect.) In the second experiment they again used the infrared sensors but they also asked the nominal experimenters to use a stopwatch as the sensors were said to be new and sometimes unreliable.

In the second experiment Doyen et al. were able to replicate the Bargh results. Namely, when using the stopwatch, the nominal experimenters reported that the group primed to walk slow did walk slow and they reported that the group primed to walk fast did walk fast. The results, however, were not entirely due to subtle experimenter bias because in the slow prime case the infrared sensors also found that the slow-primed group walked slow. The infrared sensors, however, did not report an increase in speed when the nominal experimenters expected an increase in speed.

Thus, the old-slow priming results appear to be due to a subtle mix of experimenter bias and standard priming which is cued or amplified via experimenter signaling. Given what are still relatively small sample sizes (50-60) the last should also be taken provisionally.

Important Addendum: Bargh has written a nasty attack on the new paper, the journal that published the paper, and Ed Yong who blogged the new paper for Discover Magazine. Bargh’s attack is a model of how not to respond to criticism new information. Ed Yong discusses Bargh’s response here. Like Yong, I am dismayed that Bargh quotes the new paper inaccurately. In his attack, Bargh also says things such as the overuse of elderly-related items reduces the effect of the prime. Yet in the methods paper he cites (and wrote) he says more prime stimuli generally results in bigger effects (p.11, effects can vary if the subjects consciously recognize the prime, a factor that the new paper tests). Bargh also entirely glosses over the main point which is that the authors did find priming effects when the experimenter knew and expected the effect to occur. Note that given the subtlety of the effects any experimenter bias appears to be entirely unintentional and Doyen never argue otherwise.

All of postwar development economics in one exchange?

Check out the book Economic Development for Latin America, edited by Howard S. Ellis and Henry C. Wallich, circa 1961 and read Paul Rosenstein-Rodan’s classic essay “Notes on the Theory of the “Big Push””.

In ten pages you get the essence of increasing returns arguments, though do see Paul Krugman’s cautionary notes about this era and its lack of formal modeling.

After those ten pages, there is then Celso Furtado, that underrated and perhaps someday forgotten Brazilian economist, who in five pages tries to take PRR apart. The big push didn’t work in Bolivia, and in conclusion

“The point is not, therefore, to show that there are indivisibilities in the production function. The main interest lies in demonstrating how processes can be modified so as to elude the effects of those indivisibilities.”

The reader is then treated to three and a half pages of Ragnar Nurske, who shores up PRR.

There is then transcribed discussion, including remarks from Theodore Schulz (he rejects big push as an analytical tool), Albert Hirschman, Howard Ellis, Henry Wallich, more from Nurske, and Haberler, who wrote:

“…the lumpy factor could often be stretched to accommodate a varying amount of the co-operating factors. The big push was no substitute for normal piecemeal progress.”

That was a popular point in those days. Hirschman also…

“doubted that as a general rule overhead facilities would create a demand for their services. This depended on the kind of entrepreneurship available. Certainly there was no fixed short-run relation between investment in overhead and other investment, since overhead could be stretched.”

Nurske then fought back. Whew!

Reading those twenty pages exhausted me, and transported me to another and earlier era. It was like watching one of those taped 1980s NBA games, as they show them in Taiwan and some other countries, without the timeouts and breaks and besides they weren’t playing much defense anyway.

Overall it raised my estimation of those economists.

Sentences to ponder

Richard H. Thaler, a former colleague at Cornell and another contributor to the Economic View column, once remarked about an unsuccessful candidate for a faculty position, “What his résumé lacked was five bad papers.”

The rest is from Bob Frank.

Markets in Everything: US Public Schools

Reuters: Across the United States, public high schools in struggling small towns are putting their empty classroom seats up for sale.

In Sharpsville, Pennsylvania, and Lake Placid, New York, in Lavaca, Arkansas, and Millinocket, Maine, administrators are aggressively recruiting international students.

They’re wooing well-off families in China, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Russia and dozens of other countries, seeking teenagers who speak decent English, have a sense of adventure – and are willing to pay as much as $30,000 for a year in an American public school.

The end goal for foreign students: Admission to a U.S. college.

So far the numbers are small. US high schools do outperform those in many other countries but the quality is modest relative to other developed countries and it’s hard for me to see this as a boom market. Nevertheless, I think I will warn my teenager that an exchange program with South Korea is an option.

Hat tip: Daniel Lippman.

Charles Murray on the role of economic forces

This has been debated by Brooks, Krugman, and around the blogosphere, so let us hear from the man himself:

“OK, let’s try this,” he said. “If you get a rising economy, for example, if Barack Obama could say we are going to bring on seven years of incredibly low unemployment, then he would argue that this would do a lot of good to the working class, wouldn’t he?” I agree. “But we already had that in the 1990s, and yet the dropout from the labour force continued to go up, people on social disability went up. Divorce went up. We have no evidence that a robust economy has much to do with these problems at all.”

I point out that many employers complain of a shortage of skills – a large chunk of America’s workforce is not as well equipped as it used to be relative to the rest of the world. If you don’t have the skills to make a living, how can you feel pride in your situation? “Well, that’s a different problem,” says Murray, looking suddenly uninterested. “If you are arguing that 22-year-old men are saying to their girlfriends, ‘I just need a job and then I’ll behave responsibly …’ Well, that’s just bullshit. If you ask women in working class communities, they will say, ‘Why should I marry these losers? It’s like taking another child into the household.’ ”

That is from his FT interview, I am not sure if it is gated for you. The closing paragraph is this:

I feel mildly guilty at having spoiled Murray’s jovial mood but he quickly bounces back. The bill arrives. I disguise my shock at its size. As we get up to leave, Murray says: “Here is an interesting commentary: I was willing to talk to the Financial Times under the influence of alcohol but I’m not willing to play poker under the influence. What does that say?” Don’t worry, I reply, you won’t lose your shirt. Murray laughs. As we are shaking hands, he adds, “I really enjoyed that. We must do it again some time.” Then he strides off in what looks to me like a straight line.

Christian card counters

Until last year, he and his high school friend from Bible camp, Ben Crawford, ran a group of more than 30 religious card counters. Based in Seattle, the rotating cast of players says it won $3.2 million over five years — all while regularly attending church, leading youth groups and studying theology.

But first Jones and his group had to wrestle with the apparent moral paradox: Should Christians be counting cards?

“My father-in-law flipped out about it,” Jones said. “I remember Ben and I discussing everything. Are we being dishonest to the casinos? Is money an evil thing?”

Group members believed what they were doing was consistent with their faith because they felt they were taking money away from an evil enterprise. Further, they did not believe that counting cards was inherently a bad thing; rather, it was merely using math skills in a game of chance. They treated their winnings as income from a job and used it for all manner of expenses.

The article is here, hat tip goes to Mo Costandi.

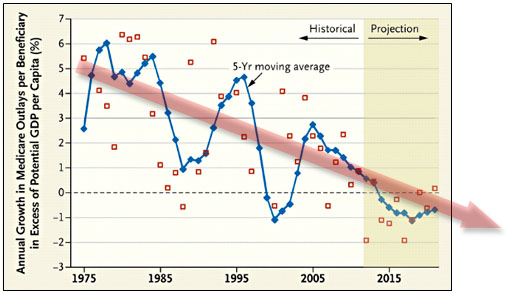

Is Medicare cost growth slowing down?

A lot is at stake here. Kevin Drum has a good summary of some recent work:

Via Sarah Kliff, a pair of researchers have taken a look at per-capita Medicare spending and concluded that it’s on a long-term downward path which is likely to continue into the future. Their claim is pretty simple: Although Medicare’s sustainable growth rate formula has been overridden year after year (this is the infamous annual “doc fix”), they say that other attempts to rein in spending have actually been pretty effective. This suggests that the cost controls in Obamacare have a pretty good chance of being effective too. Their basic chart is below, and since we’re all about the value-added around here I’ve added a colorful red arrow to indicate the trajectory.

(Note that their calculations are based on potential GDP, not actual GDP. I’m not sure why, but I assume it’s to control for the effects of recessions and boom years.)

Now, this calculation is per beneficiary, which means that overall Medicare costs will still go up if the number of beneficiaries goes up — which it will for the next few decades as the baby boomer generation ages. There’s really nothing to be done about that, though. Demographic bills just have to be paid. Nonetheless, if we can manage to keep benefits per beneficiary stable compared to GDP we’ll be in pretty good shape.

While I would say “too soon to tell” (for me only the post-2005 data points mean very much vis-a-vis the original question), I would not dismiss such reports out of hand.

Robert Shiller’s new book

Three on Launching

1. The excellent Reihan Salam writes, “Tabarrok’s Launching the Innovation Renaissance is my favorite manifesto in years. In a better world, it would be the roadmap for the U.S. center-right.” Small steps towards a much better world, Reihan!

2. A truly Straussian Straussian Reading of Launching the Innovation Renaissance.

3. I will be speaking at Inventing the Future: What’s Next for Patent Reform at AEI in Washington, DC on Wed. March 14, 12:30-2:00.

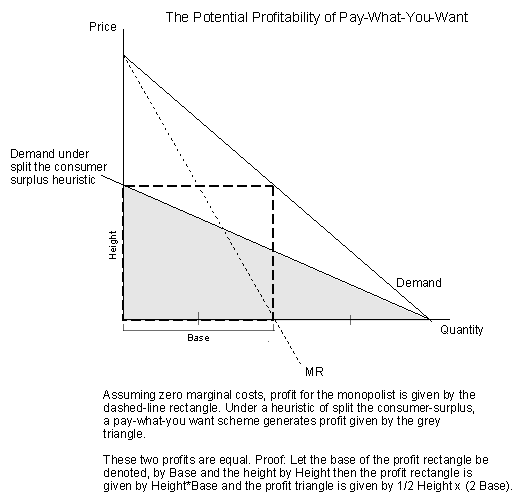

Some Economics of Pay What You Want Pricing

A number of musicians and game developers have experimented with pay-what-you-want pricing (e.g. see the important field experiment by Gneezy et al. and less formal reports from Radiohead, Norwegian composer Gisle Martens Meyer and the video-game makers 2D Boy and Joost van Dongen.)

Imagine that under the pay-what-you-want model consumers choose to split their consumer-surplus with the seller. Here is a neat little proof for the linear demand case that under this heuristic profits are as large as under monopoly pricing! I have also assumed MC of zero which makes sense for digital goods and is also quite important to the result as pay-what-you-want can result in negative profits should consumers choose to pay less than marginal cost.

Split the consumer surplus is optimistic for the seller although splitting the gains does happen quite often in the dictator game so it is not without interest. Probably more importantly, pay-what-you-want pricing is going to be advantageous when the seller also sells a complementary good, such as concerts, which benefit from consumption spillovers from the pay-what-you-want good.

Matt’s new book

As I had predicted, it is very good. Most of all I like the suggestion that the economy is becoming more Ricardian with higher resource rents.

I am assuming that most of the United States will not follow Matt’s policy prescriptions, which are unpopular with homeowners to say the least. Which secondary adjustments and rent-seeking losses will result? If you cannot easily live in Manhattan, next to the stylish people, how will you respond? One option is to damn them and tune into NASCAR. Instead you might compete more intensely for their attention and approval. Write a blog. Send them ads. Try to chip away at the privileged status of their attention and capture some of that value for yourself. Either way cultural polarization seems to increase.

For all their other virtues, lower rents also help satisfy the demand for affiliation. I know people who are proud just to live in San Francisco and not only because it signals their income and status. It sounds cool. At what level of zoning is this consumer surplus maximized?

What is the most serious estimate of how much denser agglomeration — boosted by lower rents — would increase productivity? I do not take the urban wage premium as the correct measure here, since at the margin the extra worker currently does not move in. I would like to read a good study of this issue, which I have discussed with Ryan Avent as well.

Is this available improvement a level effect or a rate effect?

If people were the size of ants, without encountering any absurdities of physics or biology, how would the “public choice” of urban building change? Would urban centers be equally exclusionary?

How much space do we need to live? Say you have a 3-D printer nanobox which can produce (or obliterate) any output on demand. Is a studio apartment then enough? Just print out your bed come 11 p.m., or summon up your kitchen equipment before the dinner party. How much of the demand for space is for storage and how much is for other motives? My personal demand for space is highly storage-intensive, but I may be an exception in this regard.

If zoning stays too tight, are there (second best) general negative externalities from storage?

I don’t recall Matt calling for the widespread privatization of government-owned land, but would he agree this is the logical next step? It’s hardly as important as freeing up more urban and suburban building, but is there any good reason for government to own all that turf? I don’t think so. Let’s keep the public works and military facilities and national parks, and sell most of the rest.

Here is Matt’s summary of the book.

The evolution of labor markets, most of all in Spain

Temporary contracts were introduced in a labor reform approved in 1984 by the Socialist government of Felipe González, and they have remained in favor ever since – even more so during times of crisis, such as those currently being seen in Spain, where 93 out of every 100 contracts signed of late have been temporary.

Here is more.

*The Rent is Too Damn High*

The new eBook from Matt Yglesias is out today, I will likely read (and finish!) my copy tonight. Self-recommending, you can get one here.

Democracy, wealth, and local stimulus spending

Paul Krugman asked a good question yesterday: “…if states and localities can borrow freely, how do you explain the drastic fall in their spending I have been documenting?”

This is maybe too literal an answer to address his macroeconomic concerns, but I view state and local government spending as falling because voters wanted it to, either directly or indirectly. Inflation-adjusted net worth per capita is still below the level of the late 1990s, and not returning any time quickly (an important point), and so voters/spenders wanted to cut back somewhere. Local government is the target they chose, and not just in the Red states. My point is not that the median voter is all-wise, but rather the Austerians are the guy next door. Voters apparently don’t see marginal local government activity as having the same value as cash in their pockets. There still may be a role for a federal fiscal bridge to ease the transition, but in democratic systems some expenditure declines are in the cards, just as the rollicking revenues of earlier years led to big boosts in state and local spending. We are not as wealthy as we thought we were, and greater federal borrowing can blunt this reality only to some extent. The notion of a voter ideal point ought to somewhere enter the analysis.

A few months ago I saw a tweet — I forget from whom — noting that the economy would be (would have been) booming if only not for the state and local cutbacks. I differ from that perspective, and I would rephrase it as the (not false) claim that the economy would be booming if only we were wealthier.

I’ve yet to see a good analysis of how freely state and local governments can borrow at the margin, especially in response to a decline in tax revenues. Many bloggers have attacked this piece by John Taylor (pdf), as Taylor argued that the stimulus aid led to a corresponding reduction in state and local borrowing. We still don’t know if this is true, but do we know that it is false? The arguments against Taylor consist of little more than saying he cannot be right. Check out the graph on Taylor’s p.5, noting that inverse correlation is not the same as causality. It’s striking nonetheless, as state and local borrowing goes down as receipts from the federal government go up. Constitutional balanced budget requirements may or may not bind, as many state and local governments can “borrow” quite readily by adjusting contributions to their pension funds, among other moves.

A related question is how voters understand the ability of their state and local governments to spend more by “borrowing” against pension funds, or changing accounting, or in other words what they saw as the opportunity cost of continuing previous levels of public spending at the state and local levels.

My view in 2009 was that federal aid to state and local governments was the one part of the stimulus bill which made sense. It is easier to preserve old jobs than to create new ones. Still, when it comes to analyzing the state and local cutbacks, and the effectiveness of federal aid, we don’t have a lot of clear answers.