Category: Economics

Possible Greek facts

It was funny when the first Greek bond hit a yield of 100 per cent, says investment editor James Mackintosh. But Greece may be the proud issuer of the first bond to yield more than 1,000 per cent outside periods of hyperinflation.

The explanatory video is here.

Studies of the value of private equity

Here is a very useful survey by Steven M. Davidoff, excerpt:

…in a separate paper, Steven Kaplan of the University of Chicago and Mr. Stromberg estimated that private equity-owned firms had a default rate of 1.2 percent a year from 1980 to 2002. That compares with Moody’s Investors Service’s reported default rate of 1.6 percent for all corporate bond issuers in the United States in the same time period.

Private equity-owned companies may have a lower general default rate because of the better debt terms that sophisticated private equity firms can negotiate. For example, Moody’s has found that an outsize number of companies owned by private equity firms avoided default during the financial crisis because they had so-called covenant-lite debt, which had fewer terms that could be violated.

Beyond default rates, evidence of the private equity industry’s ability to create value is still surprisingly uncertain, given that the industry has more than 30 years of history. One of the reasons is that private equity firms do not generally publicly disclose the performance of their buyouts.

…A new paper, however, finds evidence that private equity firms do add value. Adam C. Kolasinski and Jarrad Harford of the University of Washington examined 788 large private equity buyouts in the United States. They found that private equity-owned companies invested more efficiently than other companies, a fact the authors attributed to private equity firms’ greater access to capital. The authors also found that the payment of large dividends to private equity firms, a common practice, did not create future financial distress.

There is more of interest at the link. “Some positives, lots of uncertainty” would be a good description of the available evidence.

Sentences to ponder, the eurozone crisis as political failure

Italian Prime Minister Mario Monti’s program includes no general wage cuts. In Portugal, the government abandoned attempts to engineer unit labor cost reductions through “internal devaluation” after meeting political opposition. In Ireland, the Croke Park accord prevents the government from further reducing public-sector wages. Despite nearly two years of troika programs, Greek unit labor costs have hardly budged.

That is from Peter Boone and Simon Johnson (pdf). Here is another batch:

Once risk premiums are incorporated in debt, Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Italy do not appear solvent. For example, with a debt/GDP ratio of 120 percent and a 500-basis-point risk premium, Italy would need to maintain a 6 percent of GDP larger primary surplus to keep its debt stock stable relative to the size of its economy. This is unlikely to be politically sustainable.

I am not suggesting that a 6 percent of gdp primary surplus is easy. Nonetheless some countries are unwilling to do it. One is free to take a Keynesian view of how spending cuts damage gdp in the short run. Even then, Italy could combine an increase in private debt with wealth transfers (e.g., give creditors a mortgage share in Italian homes), but of course they don’t want to. Today, Italy could still enjoy a living standard better than what the country had in the 1980s, when everyone was calling it so dynamic (not your grandfather’s Versailles Treaty). That’s no longer good enough.

Critics get it wrong when they blame the euro crisis on “too much socialism.” For one thing excess public ownership is only a secondary problem (while a problem), for another thing Sweden is doing fine. When it comes to “failure to remedy the euro crisis,” as opposed to initial causes, let’s look long and hard at “unwillingness to consider solutions which admit that citizens’ standards of living will fall.” That’s not socialism, but it is one pernicious form of modern interventionism and you will find it very much here in America too.

On a somewhat different note, here is a good blog post on the shortening of collateral chains, and how the ECB’s policies are hitting at some REPO markets.

A good paper and model of (part of) the financial crisis

From Gary B. Gorton and Guillermo Ordonez (pdf):

Short-term collateralized debt, private money, is efficient if agents are willing to lend without producing costly information about the collateral backing the debt. When the economy relies on such informationally-insensitive debt, firms with low quality collateral can borrow, generating a credit boom and an increase in output. Financial fragility builds up over time as information about counterparties decays. A crisis occurs when a small shock causes agents to suddenly have incentives to produce information, leading to a decline in output. A social planner would produce more information than private agents, but would not always want to eliminate fragility.

What are the effects of private equity?

There is a recent two-part series by Steve Kaplan, arguably the leading researcher in the area. Here is part one and here is an excerpt:

Some, including presidential candidates Newt Gingrich and Rick Perry, criticize private equity for gutting companies and destroying jobs. The private equity industry and Mitt Romney argue that private equity creates jobs. The best empirical evidence—co-authored by one of my colleagues, Steve Davis—says the answer is that private equity both creates and eliminates jobs.3After a buyout, employment in existing operations tends to decline relative to other companies in the same industry by about 3 percent. Many of those job losses are undoubtedly painful.

At the same time, however, employment in new operations tends to increase relative to other companies in the same industry by more than 2 percent. Davis et al. conclude that “the overall impact of private equity transactions on firm-level employment growth is quite modest.”

Here is part two, which focuses on Bain.

Very good sentences

There was a quote from Stephen Jen of SLJ Macro Partners doing the rounds last week, to the effect that the three-year LTRO could have kept even Bernie Madoff afloat.

Here is more.

What would a sovereign debt crisis look like in the United States?

There is a new Econ Journal Watch symposium on this topic, with contributions from Arnold Kling, Garett Jones, Peter Wallison, Joseph Minarik, and Jeffrey Rogers Hummel, recommended. I am myself closest to the views of Garett Jones. Here is a related video.

An Economic and Rational Choice Approach to the Autism Spectrum and Human Neurodiversity

That is a new paper of mine, you will find the link here. Here is the abstract:

This paper considers an economic approach to autistic individuals, as a window for understanding autism, as a new and growing branch of neuroeconomics (how does behavior vary with neurology?), and as a foil for better understanding non-autistics and their cognitive biases. The relevant economic predictions for autistics involve greater specialization in production and consumption, lower price elasticities of supply and demand, a higher return from choosing features of their environment, less effective use of social focal points, and higher relative returns as economic growth and specialization proceed. There is also evidence that autistics are less subject to framing effects and more rational on the receiving end of ultimatum games. Considering autistics modifies some of the standard results from economic theories of the family and the economics of discrimination. Although there are likely more than seventy million autistic individuals worldwide, the topic has been understudied by economists. An economic approach also helps us see shortcomings in the “pure disorder” models of autism.

Some of you have asked me about the recent debates over the forthcoming DSM-V and autism (and here pdf) , here is one bit:

It is still possible to adhere to a DSM approach for practical fieldwork, and “autism identification,” while rejecting it as our best possible understanding of autism. Under one view, DSM does not “define” autism but rather the DSM standards provide useful information for identifying autistics who require assistance. Alternatively, in the context of both insurance companies and schools, DSM standards allow payments to be triggered if an individual is judged to be autistic according to the specified criteria. For systems of financial transfer to prove workable, perhaps the relevant legal definitions have to cite unfavorable outcomes rather than defining autism in a more fundamental way. We’ll return to this issue when we consider discrimination. For now the point is that the DSM standards don’t have to be applied to every autism-relevant question and should not be viewed as necessarily trumping other approaches.

The DSM standards also evolve. DSM-III defined autism differently than did DSM-IV and DSM-V will differ as well. It’s well known that the DSM process itself is, for better or worse, heavily influenced by various interest groups, including pharmaceutical lobbies. So DSM approaches have to be judged by some external standard and the cognitive profile approach (and a concomitant rational choice approach) can assist in this endeavor. Again, the DSM standard should not be construed as ruling out competing or more fundamental approaches.

Why isn’t the iPhone made in America?

This is an excellent article, and perhaps it will win one of David Brooks’s Sidney Awards, excerpt:

Another critical advantage for Apple was that China provided engineers at a scale the United States could not match. Apple’s executives had estimated that about 8,700 industrial engineers were needed to oversee and guide the 200,000 assembly-line workers eventually involved in manufacturing iPhones. The company’s analysts had forecast it would take as long as nine months to find that many qualified engineers in the United States.

In China, it took 15 days.

…Foxconn employs nearly 300 guards to direct foot traffic so workers are not crushed in doorway bottlenecks. The facility’s central kitchen cooks an average of three tons of pork and 13 tons of rice a day. While factories are spotless, the air inside nearby teahouses is hazy with the smoke and stench of cigarettes.

Foxconn Technology has dozens of facilities in Asia and Eastern Europe, and in Mexico and Brazil, and it assembles an estimated 40 percent of the world’s consumer electronics for customers like Amazon, Dell, Hewlett-Packard, Motorola, Nintendo, Nokia, Samsung and Sony.

“They could hire 3,000 people overnight,” said Jennifer Rigoni, who was Apple’s worldwide supply demand manager until 2010, but declined to discuss specifics of her work. “What U.S. plant can find 3,000 people overnight and convince them to live in dorms?”

Most of all, I like how the article shows that some Chinese economic advantages result from scale, speed, flexibility, and the supply chain, more than just from lower wages per se. I believe we need a rethink of the current importance of economies of scale and scope, and what they actually consist of.

Some new books in my pile

I am learning a good deal from Stephen Bainbridge’s Corporate Governance After the Financial Crisis:

There seems little doubt that the monitoring model has influenced board behavior. In 1995, only one in eight CEOs [of those stepping down] was fired or resigned under board pressure. By 2006, however, almost a third of CEOs were terminated involuntarily. Over the last several decades, the average CEO tenure has decreased, which also has been attributed to more active board oversight.

I cannot say I am personally so interested in the topic of Ed Leamer’s The Craft of Economics: Lessons from the Heckscher-Ohlin Framework, but he is a master of exposition for complex economic results and this book is no exception.

Daniel Hausman’s Preference, Value, Choice and Welfare reflects his characteristic intelligence and judgment and it should be read by anyone with an interest in economic methodology.

Johan van Overtveldt’s The End of the Euro is a very good book on the background leading up to the current euro crisis; also useful is David Marsh’s The Euro: The Battle for the New Global Currency.

I still think Michael Nielsen’s Reinventing Discovery: The New Era of Networked Science is an important book on an important topic.

Tale of a published article

From Joshua Gans:

But people are wrong on the Internet all of the time. So what really annoyed me was how Cowen ended the post:

“This counterintuitive conclusion is one reason why we have economic models.”

…Now where did all that lead? Frustrated by the blog debate, I decided to write a proper academic paper. That took a little time. In the review process, the reviewers had great suggestions and the work expanded. To follow through on them I had a student, Vivienne Groves, help work on some extensions and she did such a great job she became a co-author on the paper. The paper was accepted and today was published in the Journal of Economics and Management Strategy; almost 5 years after Tyler Cowen’s initial post. And the conclusion: everyone in the blog debate was a little right but also wrong in the blanket conclusions (including myself).

The rest of the story is here. Stephen Williamson serves up a different attitude, and here is Paul Krugman’s very good post on open science and the internet.

From my inbox

I feel like the young economist bloggers of the world need some advice, but I don’t have the stature, experience, or age to give it.

Working for a consulting company I’m fairly detached from the academic world, but we are staffed with PhD economists and we do hire grad students. When I read stuff that, for instance, REDACTED writes, in the tone that he writes it, I know that at my company if he were a potential hire we would a) Google him, and b) this would hurt his chances. This isn’t about political leanings either. My liberal colleagues would look at his writings with the same distaste and worry that my conservative colleagues would.

Is this the same way it is in academia? Should young economist (and other academic) bloggers be more careful than many seem to be? Are they hurting their job market chances? Because that is my impression.

That is another reason for polite discourse, namely that it improves the career prospects and quality of one’s readers and followers. The best reason, however, is still that it improves one’s own thought processes and that is a point of substance not just style or manners. I’ve seen that point ignored a lot in the commentary of the last few weeks but not once seriously disputed.

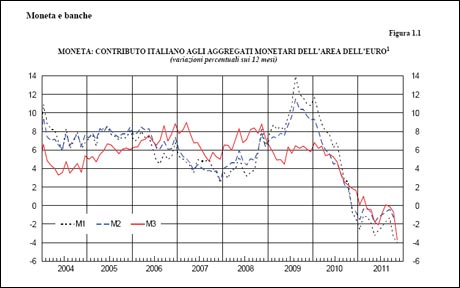

M3 in Italy

The link is here. There is a lot of talk of self-defeating austerity, and I agree that spending cuts often lead to real and nominal gdp declines in the short run, but most likely this is the critical problem, including in Greece.

For the pointer I thank Antony Slumbers.

Steve Murdock is not looking for a handout

Steve is doing some jobs, but it could not be said that he has a job in the traditional sense:

During the previous month, he had taken to picking up cans and scrap metal along the road. It made him feel like a bum, he said, but he had managed to fill seven bags with aluminum cans and other recyclables. Now he loaded them into a friend’s pickup truck and drove a few miles south, toward Myrtle Beach. They pulled up to a warehouse where the owner purchased scrap metal. Murdock grabbed his bags and set them onto an industrial scale, stale beer spilling onto his hands and his jeans.

“Twenty-seven pounds at 35 cents per pound,” an employee said. He punched the numbers into a calculator, rounded up and handed Murdock $9.50.

It is difficult for me to see how Murdock’s predicament — is it a typical one? — is well-described by the theory of nominal wage rigidity. I don’t mean to bait Scott Sumner, but I will again mention the difference between “nominal aggregate demand” and “real aggregate demand.” If society were much more prosperous and people had higher real wealth-backed demands to buy a lot more products, Murdock probably could get a traditional job of the kind he is seeking. In this sense you can attribute Murdock’s joblessness to a shortfall in aggregate demand. That said, it is not clear why juicing up nominal variables should do very much for him. His wage and workplace condition demands are already quite flexible, as he is willing to settle for what he can get. Is money illusion his problem? It seems there is no need to trick him, using monetary policy, into a lower real wage.

The article is here.

Addendum: Scott Sumner responds. In my view if it is a job worth creating, the private sector will expand V, or credit, endogenously, so while I believe we are on an excessively low NGDP path I do not blame that for the fate of Steve Murdock.

ADA to Dental Practioniers: You Can’t Handle the Tooth!

From an article at Governing.com:

…dental care is hard to come by in underserved areas of the country. Try finding a dentist in the remotest rural or deepest urban pockets of the land, and for blatantly economic reasons, they just aren’t there. That’s why states are looking to fix the problem by creating a so-called mid-level dental provider. Much like a nurse practitioner (NP) or physician assistant (PA) is to a doctor, this provider would be educated and licensed to perform basic dental services — routine checkups, cleanings, filling cavities and extracting teeth — under the supervision of a fully trained dentist.

…Yet in much the same way that the American Medical Association fought against the creation of NPs and PAs, the American Dental Association (ADA) and its state chapters are lobbying hard to thwart state legislatures as they work to create this new level of dental care providers, who are common and well liked in other parts of the world.

…“Publicly their main objection is safety issues,” Oswald says. “They tried to discredit the model, saying the therapists were not trained to the same level as dentists. In reality, all the research around the world shows that [mid-level providers] provide as good, if not better, care. Every time they stated safety as a factor, we asked for research, which they didn’t have.”

By the way, states with tougher licensing of dentists do not have better dentistry, but they do have higher prices. Almost thirty percent of the US workforce is now required to hold a license including shampoo specialists.

Hat tip: Carpe Diem