Category: Economics

Romney v. Romney

The joke going around last week was that a liberal, a conservative and a moderate walk into a bar. “Hi Mitt,” says the bartender. Here’s Mitt proving the point:

“This week, President Obama will release a budget that won’t take any meaningful steps toward solving our entitlement crisis,” Romney said in a statement e-mailed to reporters. “The president has failed to offer a single serious idea to save Social Security and is the only president in modern history to cut Medicare benefits for seniors.”

Hat tip on this one to Paul Krugman.

Seven ways to improve U.S. infrastructure spending

Here is a column full of good sense from Edward Glaeser, excerpt:

SPLIT UP THE PORT AUTHORITY: Last week gave us another painful audit of the work by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey to manage the World Trade Center site. I’m not going to pile on, but this super-entity is too big to succeed. How can the Port Authority possibly focus on tasks such as making New York’s airports more functional when it has so much else on its plate?

The problems at John F. Kennedy International Airport aren’t evidence of the need for a new federal infrastructure agenda, they indicate only that the Port Authority has too much to do. Splitting off the airports, probably into two separate entities (for New York and New Jersey), could generate managerial focus and more competition. The airports can fund themselves if they are free to charge higher landing fees. Millions of fliers into New York should be perfectly willing to pay a bit more to ensure a more pleasant experience. More nimble and less restricted airports would help that happen.

It is one of my “hobby horses” to note that for all the money we spent on fiscal stimulus, air transport in and out of America’s major city remains a total, unworkable mess.

Bubbles and economic potential and potential gdp

Here is a Krugman post on the question, here are earlier posts from Sumner and Yglesias. I will put my remarks under the fold…This topic is easiest to understand if you sub out the United States and sub in Greece. There is no AD boost that can (anytime soon, without a lot of extra growth kicking in), restore Greece to its previous output peak and its previously expected performance-to-come. Circa 2006, Greece was in an unsustainable position, if for no other reason the market didn’t understand the correct risk premium for Greece. Once the correct risk premium is applied, Greek output falls and furthermore numerous (related) bad events kick in and also a whole set of previous plans are shown to be unsustainable (and no this doesn’t have to be an Austrian argument!). The gap between Greece’s current path, and the path previously envisioned for Greece is thus:

a. part AD gap which can be fixed by AD policy

b. part a difference in risk premia, and for Greece the old risk premium, when the country borrowed at very low rates, was wrong and is gone more or less forever. The concomitant financial and fiscal stability is gone too.

c. part a difference in enthusiasm in supply, based on the differences between earlier expectations that “get rich quick” really does apply to Greece, and the current more pessimistic expectation that “get rich quick” is now unlikely, and thus “smaller-scale, scrabble-around projects just to make ends meet” are the order of the day. DeLong gets at some of this here.

Greece does have to rebuild a) — don’t get sucked into aggregate demand denialism! — but it also has to rebuild b) and c) and perhaps other factors too. This follows rather directly from — dare I breathe the words? — the synthetic real business cycle/neo Keynesian models which form the backbone of contemporary macroeconomics and which Krugman apparently still doesn’t wish to recognize. (To various commentators and other bloggers: when I write macro on this blog I usually take knowledge of these models for granted; if you don’t know those models that is fine, call me arcane, but it doesn’t mean I am the one who is wrong.) Krugman runs through a bunch of weak arguments and responses, and counters them well enough, but he doesn’t see or consider the baseline response that would follow from standard contemporary macro, with the possible exception of his brief parenthetical phrase about credit conditions.

Turning for a moment to broader points, the astute reader will note that in this framework the current sluggishness of recovery need not be evidence for Old Keynesianism. An ineffective response to fiscal policy does not per se have to mean we just didn’t do enough fiscal policy. And so on. Maybe yes, maybe no, but all of a sudden there is a lot more room for agnosticism about macroeconomics and more broadly there is more room for epistemic modesty.

Contra Tim Duy, you can hold this mixed view without wanting to see the Fed raise interest rates. Just avoid the AD denialism.

Krugman defines “potential GDP is a measure of how much the economy can produce” but keep in mind that this quite possibly won’t be a unique number. With what risk premium? With what enthusiasm of supply? See my Risk and Business Cycles for an extended discussion and also numerous citations.

It’s also worth noting that while gdp is a useful “we can all agree upon what to measure” kind of concept, its real meaning is conceptually fairly slippery and “potential gdp” is not likely to be better pinned down at its foundations. Let’s not reify that concept above and beyond what it is worth.

In any case, we can be agnostic about the size of the potential gdp gap with regard to the United States today and indeed my original post very carefully used a question mark in its title. But there is no incoherence to assert that part of the apparent gap is due to the real side. The new learning about America is not about the correct risk premium for our debt (not yet at least), but about our financial fragility, how well our politics responds to crises, some worrying long-term trends in the labor market, possible misreadings of the productivity numbers, and a few other real factors. It really is possible that previous investment plans were based on expectations of the real economy that were wrong and unsustainable and now have been (partially?) corrected, with negative growth penalties looking forward.

Stephen Williamson offers very detailed comment, noting also that the recession started well over four years ago, which gives plenty of time for nominal resets, and we’ve seen no downward cascading spiral, so maybe there is a non-AD problem with getting back on track at the preferred rate. He also eschews AD denialism. Today Krugman has a brief note along the lines that the views of his opponents on these questions are “even worse than your first impression” but that is best thought of as a) his occasional churlishness, and that b) his writings on this topic do not, at least not to date, reflect a very thorough knowledge of the relevant literature(s).

Dividends and taxation

President Obama wants to tax dividends at ordinary income rates. These results, from Marcus and Martin Jacob, should not come as a huge surprise:

We compile a comprehensive international dividend and capital gains tax data set to study tax explanations of corporate payouts for a panel of 6,416 firms from 25 countries for 1990-2008. We find robust evidence that the tax penalty on dividends versus capital gains is statistically significant and negatively related to firms’ propensity to pay dividends, initiate such payments, and the amount of dividends paid. Our analysis further reveals that an increase in the dividend tax penalty raises firms’ likelihood to repurchase shares, initiate such repurchases, and the amount of shares repurchased. This is strong confirming evidence that when listed industrial firms globally design their payout policies, they take into careful consideration the relative tax implications of their payout choices.

Here are some Finnish results:

Using register-based panel data covering all Finnish firms in 1999-2004, we examine how corporations anticipated the 2005 dividend tax increase via changes in their dividend and investment policies. The Finnish capital and corporate income tax reform of 2005 creates a useful opportunity to measure this behaviour, since it involves exogenous variation in the tax treatment of different types of firms. The estimation results reveal that those firms that anticipated a dividend tax hike increased their dividend payouts by 10-50 per cent. This increase was not accompanied by a reduction in investment activities, but rather was associated with increased indebtedness in non-listed firms. The results also suggest that the timing of dividend distributions probably offsets much of the potential for increased dividend tax revenue following the reform.

Here are more results from Finland. In the UK dividend tax increase of 1997 it seems pension funds were the marginal investor and they bore much of the burden from that particular reform.

Innovation Nation v. Warfare-Welfare State (more)

The New York Times has a lengthy piece on the expansion of the welfare state:

The government safety net was created to keep Americans from abject poverty, but the poorest households no longer receive a majority of government benefits.

…Dozens of benefits programs provided an average of $6,583 for each man, woman and child in the county in 2009, a 69 percent increase from 2000 after adjusting for inflation.

…The recent recession increased dependence on government, and stronger economic growth would reduce demand for programs like unemployment benefits. But the long-term trend is clear. Over the next 25 years, as the population ages and medical costs climb, the budget office projects that benefits programs will grow faster than any other part of government, driving the federal debt to dangerous heights.

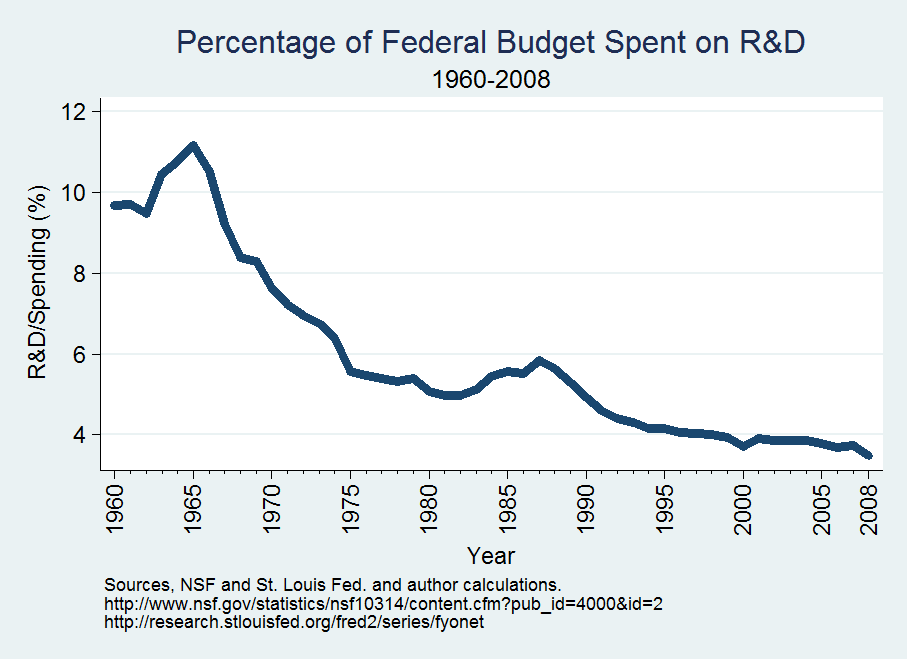

In Launching the Innovation Renaissance (and here) I argue that the warfare-welfare state is crowding out other areas of spending, even when such spending could be highly valuable.

Wealth externalities and limited liability in banking

Arnold Kling writes:

Suppose that you sell your shares in Shakee Bank to me today, and tomorrow Shakee has to be taken over by the FDIC. Am I liable for losses, which probably were caused by decisions made before I bought my shares? Suppose that Shakee has accumulated $8 billion in losses, and all its shareholders of record obtained their shares for a collective $0.10. What happens then?

I don’t envision the FDIC being eliminated, but say the government is in a position to be picking up some potential bondholder losses. Under one version of the reform, bank shareholders already have posted extra collateral, by requirement of the law. That is somewhat like higher bank capital requirements, with the twist that there is now a new legal class of bank capital.

That is an improvement over the status quo, but it’s not the most innovative form of the proposal. One alternative version is for the government to outsource the enforcement to the bank itself. For instance the regulator can say: “as insolvency approaches, the bank is liable for 1.5 to 1, it can come up with the money any way it wants. If it can’t come up with the money, we will take the major shareholders of record, say a year before the event (or consider a more complicated weighted average of this variable) and send them an income tax assessment for 2-1.”

The bank might preemptively organize like a partnership, or it might apply its own collateral and capital requirements to the shareholders, or it might find some other way of meeting the obligation. Banks would compete to find the better solutions.

In response, many people fear banks trying to set up with only hobo shareholders. That would avoid the 2-1 or 1.5 to 1 or whatever, because hobos don’t have extra assets to attach. I just don’t think those banks will become major money center institutions because the quality of shareholders really does matter at some level. For instance such banks could not have wealthy, highly motivated, equity-holding CEOs. Most likely hobo banks would stay small and thus skirt the too big to fail problem or maybe they would not exist in the first place.

One problem with traditional capital requirements is that the government ends up making comovement-inducing ex ante decisions about which assets count toward satisfying the capital requirement. Remember AAA CDOs in America and AAA government securities in Europe? Under non-limited liability, only cash is accepted but it only has to be delivered ex post in the case of failure. The regulations themselves need not create the same kinds of uniformity, misjudgments, and excess systemic risks up front.

One tricky question is how to apply non-limited liability to foreign banks operating in the United States. This is a problem with all regulatory schemes based on less than perfect international coordination. The first cut approach is to insist on non-limited liability for U.S. operations, though of course evasion and reclassification of operations may occur.

Mark Thoma adds lengthy comments. Here is a very relevant paper by Claire Hill and Richard Painter, and a blog post by them. Here is Suzanne McGee. Here are some debates on non-limited liability in economic history, including work by Lawrence H. White.

Gordon Tullock is 90 years old today

Here are previous MR entries concerning Gordon.

The very best coverage of the new Charles Murray book

Could it be the lengthy NYT profile of Stevenson and Wolfers? Other than finding material on economists interesting per se, and knowing them a bit, I found this profile relevant for two reasons. First, successful economists really can earn a good amount these days, and at relatively young ages. They could probably earn much more, if that is what they set out to do. Second, there really is a cognitive elite engaged in assortative mating, and the children of those couples will have a big head start. Furthermore that cognitive elite is now global (Justin is from Australia). No, Murray’s econometrics do not demonstrate all of his conclusions, but nonetheless this family is a walking embodiment of The Bell Curve, not to mention the new book. (I would have preferred a piece which explored this irony with more depth.) Some of you are negative in the comments on my post, but the facts about the Wolfers/Stevenson family are hardly exceptional, conditional on a few other variables but of course strongly conditional on those variables. They own a Noguchi table, we own a Noguchi lamp (cheaper than you think, by the way). They ban sugar, we do not, but there is no junk food, sugary or otherwise, kept around our house. My professional writing rails against junk food. I was disappointed that their nanny has only a Master’s degree. The nanny in our family has a Ph.d and is a well-known economics blogger.; going back in time, the two other nannies were a professional linguist and translator and an engineer (they are sometimes called “the grandparents”). Get the picture? The rhetoric in the profile is oddly non-self-conscious, perhaps in a way that makes the couple look less charismatic than they really are, and that too is worth thinking about. Parts of the profile felt like a bit of a slog to me (despite my interest in the topic), but I suspect not to most NYT readers, and of course we are seeing a highly skilled and experienced journalist at work along with a first-rate team of editors.

Always try to give things the more subtle reading.

Profile of Justin Wolfers and Betsey Stevenson

It is here, charming piece, four clicks to get through the whole thing. Here is one bit:

They have one child, but there are two strollers, a Bugaboo and a Bob baby jogger, parked in the front hall of their stylish home here. Their daughter, Matilda, who is almost 2 1/2 , attends classes in art, music and soccer. She is not allowed to eat any meat or sugar, not even in birthday cake.

And:

Their home in Philadelphia, in a historic building that once housed an African-American publishing house, features soaring ceilings and custom iron work. A glass-top Noguchi coffee table is in the living room, next to a white Jonathan Adler casting couch covered in a sheepskin throw from Costco. In the attic is a home gym with a treadmill, a boxing bag, a recumbent bicycle and a flat-screen television.

Matilda’s nanny has a Master’s degree. Here is Justin’s mother:

“Out of all my children he was, and still is, the most emotional,” Ms. Wolfers wrote in an e-mail. “Any attempts to hide his feelings, positive or negative, are doomed to failure. This seems to be at odds with his belief that all aspects of life can be described by an economic concept or a cold, bleak economics formula.”

My 2007 column on their work is here.

The price elasticity of contraception

Let’s try throwing out some data on this topic:

This paper uses a unique natural experiment to investigate the sensitivity of American college women’s contraceptive choice to the price of oral birth control and the importance of its use on educational and health outcomes. With the passage of the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005, Congress inadvertently and unexpectedly increased the effective price of birth control pills (“the Pill”) at college health centers more than three-fold, from $5 to $10 a month to between $30 and $50 a month. Using quasi-difference-in-difference and fixed effects methodologies and an intention-to-treat (ITT) design with two different data sets, we find that this policy change reduced use of the Pill by at least 1 to 1.8 percentage points, or 2 to 4 percent, among college women, on average. For college women who lacked health insurance or carried large credit card balances, the decline was two to three times as large. Women who lack insurance and have sex infrequently appear to substitute toward emergency contraception; uninsured women who are frequent sex participants appear to substitute toward non-prescription forms of birth control. Additionally, we find small but significant decreases in frequency of intercourse and the number of sex partners, suggesting that some women may be substituting away from sexual behavior in general.

That is from Brad Hershbein (pdf). This paper (pdf) covers Bangladesh. I am not interested in providing any accompanying moral lesson, one way or the other.

From Facebook

“XXXX is becoming more and more convinced that Tyler Cowen and Alex Tabarrok‘s textbook is the big news in the field of economics education. Hope to use it for my class soon, wish I had it when I was a student.”

The second editions are now out, Micro, Macro, and a consolidated book, more information here.

Email from Bruce Caldwell

The Center for the History of Political Economy at Duke University will be hosting another Summer Institute on the History of Economics this June. The program is designed primarily for students in graduate programs in economics. Students will be competitively selected and successful applicants will receive a $2000 stipend for attending, plus free housing and reading materials. Our line-up of speakers is, I think you will agree, impressive. The deadline for applying is March 2. More information on the Summer Institute is available at our website, http://hope.econ.duke.edu/summer2012

How large is the output gap really?

Via Mark Thoma, and drawing upon James Bullard at the St. Louis Fed, MacroMania writes:

I think that Bullard makes a persuasive case that the amount of household wealth evaporated along with the crash in house prices should likely be viewed as a “permanent” (highly persistent) negative wealth shock. Standard theory (and common sense) suggests a corresponding permanent decline in consumer spending (with consumption growing along its original growth path). The implication is that the so-called “output gap” (the difference between actual and “trend” GDP) may be greatly overstated by conventional measures.

There is still not enough talk of wealth effects in current macro debates, as they are invoked only selectively. Note by the way that if you see the output gap is somewhat smaller, you will think today’s recovery is somewhat better, not in absolute terms, but relative to potential.

Here are some interesting observations about Bullard.

Addendum: Here is comment from Scott Sumner, and Matt Yglesias. You’ll note my post is itself non-committal, though I certainly do not dismiss this argument. Simplest response to Sumner and Yglesias is that we may have had a biased estimate of the previous trend, for bubble and TGS-related reasons.

Failing versus Forgetting

Bryan Caplan has a very good post on the human capital and signalling models of education. The key point is this, under the human capital model someone who forgets knowledge is no better than someone who failed to learn the same knowledge. Under the signaling model, however, failing and forgetting are very different. Bryan illustrates:

If I’d failed Spanish, I couldn’t have gone to a good college, wouldn’t have gotten into Princeton’s Ph.D. program, and probably wouldn’t be a professor. But since I’ve merely forgotten my Spanish, I’m sitting in my professorial office, loving life.

Simple truths about Greece

Greece will have to bring its current account deficit down to zero at some point.

This can happen in two ways: either Greece exports more or spends less. Adjusting the current account by spending less would require an additional fall in GDP of 25 per cent, given that in Greece only one in four US dollars of spending cuts goes abroad. This is clearly not a pretty picture. But adjusting by raising exports would require they increase by 50 per cent, not an easy feat. Achieving it through tourism alone would require the industry to triple in size – an unlikely prospect.

And this:

Here’s the bad news for Greece: in our sample of 128 countries, it had the biggest gap between its current recorded level of income and the knowledge content of its exports. Greece owes its income to borrowed foreign spending it cannot pay back. It produces no machines, no electronics and no chemicals. Of every 10 US dollars of worldwide trade in information technology, it accounts for one cent.

This problem cannot be addressed by fiscal Keynesian stimulus, by bland trade facilitation or by paying lip-service to structural adjustment as the November International Monetary Fund agreement implicitly assumes.