Category: Economics

Unoriginal, but simple, true, important, and neglected

Jesús Fernández-Villaverde, Pablo Guerrón-Quintanaz, and Juan F. Rubio-Ramírez report:

This paper examines how supply-side policies may play a role in fi ghting a low aggregate demand that traps an economy at the zero lower bound (ZLB) of nominal interest rates. Future increases in productivity or reductions in mark-ups triggered by supply-side policies generate a wealth effect that pulls current consumption and output up. Since the economy is at the ZLB, increases in the interest rates do not undo this wealth effect, as we will have in the case outside the ZLB. We illustrate this mechanism with a simple two-period New Keynesian model. We discuss possible objections to this set of policies and the relation of supply-side policies with more conventional monetary and fi scal policies.

Yes, there exists a model where the productivity shock has negative consequences, but don’t let “them” talk you into believing that model is relevant for today’s world.

The story continues

The fact that the EFSF was forced to delay its own bond issue on Wednesday has also hurt sentiment, as it calls into question not only its ability to fund Ireland and Portugal but also its value as a guarantor.

The Italian ten-year yield is now at 6.399, unsustainable territory, there is more here and here. France and Germany have jointly “demanded an answer” from Greece, about continued eurozone membership, but it’s not clear who will be around to (non-credibly) answer that question. Twitter is awash with rumors that Papendreou will be gone very, very soon. They just dismissed all of the military leadership. I believe it is now understood in Germany and France that they will be cutting Greece loose.

Here is one way to put it:

Italy is borrowing at 6.4% to lend to Greece at 3.5%. this will end well.

Meanwhile in Greece, via several loyal MR readers, there are more registered Porsche Cayennes than people reporting incomes over 50,000 euros a year. You may recall my earlier prediction:

“Enter democracy, stage right” is the next act in the play.

College has been oversold

Here, drawn from my new e-book, Launching the Innovation Renaissance (published by TED) is part of a section on college education. (See also the op-ed in IBD)

Educated people have higher wages and lower unemployment rates than the less educated so why are college students at Occupy Wall Street protests around the country demanding forgiveness for crushing student debt? The sluggish economy is tough on everyone but the students are also learning a hard lesson, going to college is not enough. You also have to study the right subjects. And American students are not studying the fields with the greatest economic potential.

Over the past 25 years the total number of students in college has increased by about 50 percent. But the number of students graduating with degrees in science, technology, engineering and math (the so-called STEM fields) has remained more or less constant. Moreover, many of today’s STEM graduates are foreign born and are taking their knowledge and skills back to their native countries.

Consider computer technology. In 2009 the U.S. graduated 37,994 students with bachelor’s degrees in computer and information science. This is not bad, but we graduated more students with computer science degrees 25 years ago! The story is the same in other technology fields such as chemical engineering, math and statistics. Few fields have changed as much in recent years as microbiology, but in 2009 we graduated just 2,480 students with bachelor’s degrees in microbiology — about the same number as 25 years ago. Who will solve the problem of antibiotic resistance?

If students aren’t studying science, technology, engineering and math, what are they studying?

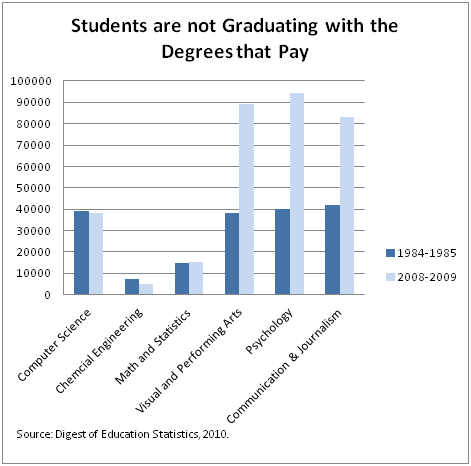

In 2009 the U.S. graduated 89,140 students in the visual and performing arts, more than in computer science, math and chemical engineering combined and more than double the number of visual and performing arts graduates in 1985.

The chart at right shows the number of bachelor’s degrees in various fields today and 25 years ago. STEM fields are flat (declining for natives) while the visual and performing arts, psychology, and communication and journalism (!) are way up.

There is nothing wrong with the arts, psychology and journalism, but graduates in these fields have lower wages and are less likely to find work in their fields than graduates in science and math. Moreover, more than half of all humanities graduates end up in jobs that don’t require college degrees and these graduates don’t get a big college bonus.

Most importantly, graduates in the arts, psychology and journalism are less likely to create the kinds of innovations that drive economic growth. Economic growth is not a magic totem to which all else must bow, but it is one of the main reasons we subsidize higher education.

The potential wage gains for college graduates go to the graduates — that’s reason enough for students to pursue a college education. We add subsidies to the mix, however, because we believe that education has positive spillover benefits that flow to society. One of the biggest of these benefits is the increase in innovation that highly educated workers theoretically bring to the economy.

As a result, an argument can be made for subsidizing students in fields with potentially large spillovers, such as microbiology, chemical engineering, nuclear physics and computer science. There is little justification for subsidizing sociology, dance and English majors.

College has been oversold. It has been oversold to students who end up dropping out or graduating with degrees that don’t help them very much in the job market. It also has been oversold to the taxpayers, who foot the bill for these subsidies.

What does the Old Keynesian economics predict here?

I will ask the Old Keynesians, here is the report from last week:

“The lack of income growth meant that the boost in spending came from a decline in the savings rate,” said David Semmens, US economist at Standard Chartered.

…The savings rate fell 0.5 per cent in the period, reaching a level last seen at the end of 2007.

I will predict that the savings rate does not substantially rise next quarter. Absolute savings will go up over some time horizon but I don’t expect it to do so immediately for cyclical reasons. Are the Old Keynesians now expecting savings to go up in some manner, due to “the paradox of savings”? After all, spending has risen. Here is a chance for Old Keynesian economics to score some points, so what will happen with savings? What does a liquidity trap model predict? Should savings be higher already, or does it take longer for that effect to kick in? How long?

Note that the New Keynesians generally do not have much to do with the paradox of savings; my view is that it may have applied to parts of 2008-2009 but is unlikely to apply today.

When it comes to Old Keynesian predictions I don’t want to count “money matters” (formerly an anti-Keynesian prediction by the way),”the recession was really bad,” or beating up on various odd right-wing views. I want forcing predictions which discriminate against the best available alternative theories.

In the comments I also would like to hear Keynesian accounts, New or Old, of why gdp growth was suddenly 2.5%, not a great number for a recovery in absolute terms, but was it the predicted number or direction, given that the stimulus was finally exhausted? I am comfortable citing “noise,” but does a liquidity trap model offer this same freedom? Doesn’t the model itself imply that one margin is what matters and you are truly “trapped”?

Drawing really long time-lines to obscure false predictions of the moment does not count as an answer!

Why is Greece turning down the “bailout”

Make no mistake about it, the decision to hold a “referendum” is a decision to turn down the deal altogether. The referendum will never be held. It is scheduled for January and the current deal, which is not even a worked out deal, won’t be on the table by then. It’s already not on the table. The opposition leader is already opposed to the referendum, there are months more of market volatility to come, the other EU powers will get skittish about the deal, how is the conscientious Slovakia supposed to feel, and how many other factors do I need to cite? And how can the Greeks decide how the referendum will be worded?

This is a way to back out of everything, under the guise of “democracy” and ex post blame the speculators and the rest of Europe. But why? Here is one on the mark take on the matter:

A plan being developed to help reduce Greece’s debts — and prevent it from becoming the first euro-zone country to default on its debts — will fall hardest on the country’s banks and the national pension system. They would face tens of billions of dollars in losses on investments in Greek government bonds.

According to data from the European Banking Authority, major Greek banks hold about $70 billion

in Greek bonds, more than one-fourth of the total held by private investors worldwide. Greece’s national pension system has about $30 billion at risk, according to local bank and corporate officials.

Even as Greece benefits from emergency debt relief included in the new bailout plan approved by European leaders last week, the Greek government will have to borrow even more money to shore up its financial system and replenish the pension fund. Greek bankers say they doubt they could come up with the money on their own.

In other words, the deal would make the country totally bankrupt. Greek voters already feel blackmailed. A good rule of thumb is that if a very unpopular government holds a referendum on something — anything — that government will lose. Seriously now, which way do you expect the Greek bus drivers to vote?

Did I mention that the Italian ten-year yield was up to 6.31%?

Update on the Austro-Chinese business cycle

Someone is sitting on a mound of $3.2 trillion in foreign exchange reserves, and yet this is possible:

With the same force that powered the most ambitious rail programme in history, China has slammed the brakes on its investment in high-speed trains.

The sudden halt has led to system-wide whiplash, leaving workers without pay, battalions of heavy machinery sitting idle and setting back plans for bullet trains that were meant to carry the nation’s future.

…Spending had already been slowing after a surge from stimulus money in 2009 but the decline since the Wenzhou crash in July has been precipitous. In year-to-date terms, investment in railways and transport had been up 7 per cent in the first half of 2011. By the end of September it was down 19 per cent, according to official data.

There is little chance of a return to the construction frenzy of the past five years but the government appears to be slowly setting the high-speed rail plans back in motion. Restarting the investment would provide an immediate boost to the weakening economy. Longer term, it is also expected to encourage a big structural shift, opening up China’s interior to make domestic growth more self-sustaining.

But this is less encouraging:

Passenger numbers have fallen sharply since the Wenzhou crash. About 151 million trips were made on Chinese trains in September, almost 30 million fewer than in July, according to ministry data.

*In Time* (spoilers about the macroeconomic model)

It is rare to see a movie with such a perfectly realized economic model, albeit one pulled from such exotic territory. Imagine a Keynes chapter 17 world where the “own rate of interest” on time — which can be borrowed and lent — rules the roost. Many people are at or near subsistence in their time endowments, and there are economies of scale in supply, so short rates on these loans are high. Those high rates choke off other investments and a version of TGS ensues. Medium-term rates, however, are negative in real terms. Carry around too much time and it will be stolen and you die. The economy has a strongly inverted yield curve and that discourages traditional financial intermediation and investment. Wealth continues to fall, which exacerbates security problems, in turning lowering the negative medium-term real rates even further. A downward spiral ensues. The only way to make money is to buy marginal security (for time endowments) and spend less on that security than you earn on short loans of time. More and more resources go into security, again exacerbating the inverted yield curve. The economics of producing security are also the fundamental source of market power in the economy. Market segmentation reigns and the marginal rates of substitution on time loans are not equated across different social classes.

The hero has read Kalecki (1943) and he operates under the assumption that a redistribution will prove isomorphic to an “Operation Twist” and restore full employment equilibrium, and positive economic growth, by fixing the inverted yield curve. But is that policy commitment credible? Does he have the support of the heroine? You have to watch the movie to find out…

In Time also raises questions about why we find time inequality more objectionable than money inequality. You also can interpret it as a model of a world where health care really works.

This is by no means a flawless film but conceptually it was stronger than I had been expecting. Kudos again to Andrew Niccol, Gattaca is a worthwhile movie too.

Here is Robin Hanson’s review, he liked it less than I did.

Animal inventory cycle problems

Michael Lynch writes to me:

The prices tell the story. A baby chimpanzee can go for as much as $50,000 (£31,195) or $60,000 (£37434). An adult chimpanzee has no market value. Abandoned adult animals end up in sanctuaries. But in one of the paradoxes of the exotics world, some of the sanctuaries that rescue animals also breed animals to defray their expenses – thereby, arguably, making the problem of surplus adults even worse.

*Engineering the Financial Crisis*

This is an excellent conceptual book on the financial crisis, full of deep research and intellectual honesty. The authors, Jeffrey Friedman and Wladimir Kraus, are not in the usual loops of the economist elite, so I hope it is not ignored. They place central importance on the Basel capital regulations and mark-to-market accounting, complemented by a credit channel, in their narrative. Arnold Kling has much more on the book. You can buy the book here; anyone interested in the financial crisis should read it. The authors have some of the best arguments against the “moral hazard” interpretations of the crisis, preferring instead knowledge and calculation arguments. My main worry is about how much the Basel regulations mattered, given that many banks held more mortgage-backed securities than Basel regulations required.

Here is a blog post on their most controversial claim in the book.

Factor endowment theories of trade and investment

The northern Scandinavian landscape is dotted with fjords, lingonberries and, if you believe some locals, elves. But another sight is increasingly common on the Arctic horizon: data centers.

Drawn by the promise of lower electricity costs, a growing number of tech companies are harnessing the region’s abundant cold air to cool their servers, cutting expensive air-conditioning out of the equation.

Facebook, the latest tech company to take the polar plunge, announced this week that it will build a data center just south of the Arctic Circle in Lulea, Sweden, where the average low in January is 3 degrees Fahrenheit.

…There are “overwhelming financial advantages” to building in the far north, according to Rakesh Kumar, an analyst with Gartner. Utilizing free outside air can result in “tens of millions, if not hundreds of millions [of dollars], of savings per year” for each site, Kumar said.

The full story is here. For the pointer I thank Steve Silberman.

The revolution which Roger Kerr hath wrought

Robots are being used to milk a herd of cows in Canterbury and the farmer who owns them says they are much healthier.

Farmer and businessman Ryan Carr of Mayfield has four robots on his farm near Ashburton which allow the cows to decide when they want to be milked.

Mr Carr told Country Life that the robotic system also means cows can eat and move at their own pace.

He says that’s doing wonders for their health and they have a longer life expectancy.

Farm production has also improved and is 4% ahead of this time last year.

Mr Carr said each unit costs about $250,000.

Here is more, hat tip goes to Chris F. Masse. You may recall that New Zealand’s market-oriented economic revolution led to a deregulation of agriculture and the elimination of most farm subsidies, and as a result the sector became more innovative.

Chris also sends along this E-Cat update, it is not something which I am able to evaluate but in expected value terms worthy of more than zero reporting, via David Price here is more from Wired.

Were non-bank banks actually a good idea all along?

I’ve been wondering that for the last few days. These entities were capped and banned in the late 1980s but once upon a time Sears Roebuck and American Express offered full banking services and their financial arms grew at a rapid clip. They took deposits but did not make commercial loans, thereby skirting banking legislation at the time and, I believe, avoiding FDIC premiums.

The big debate today is how to get more capitalization for the banks, and we have such absurdities as Basel III, not bad in spirit but somehow wishing that a bunch of essentially insolvent institutions magically had another $700 billion or so. I say the way to recapitalize banks is to keep them well capitalized to begin with. Indeed, we just bought a new microwave at Sears the other night. These institutions have a lot of commercial capital on the line.

At the time non-bank banks were banned because many people feared — and I can see why –that the non-bank banks would take big risks, backed ultimately by taxpayer money. (The banks also didn’t like the “unfair competition” and indeed it was unfair but of course it would have been fair had the model been allowed to spread more widely, allow more of them or by allowing commercial affiliation more generally, even mixed with commercial lending.) Prescient, no? Well, sort of. In reality, it turned out that the non-non-bank banks (i.e., the banks) did that anyway. With all the financial instruments and risky loans around, it is so much an extra problem that Sears Roebuck might initiate an overly aggressive lawnmower marketing strategy? I don’t know.

I do see the potential downside to the non-bank bank model, namely that systemic risk can become bigger yet through the traditional commercial sector. Not every company is as safe as Sears and even Sears has not always been safe. Still, at a time when the radicals amongst us wish that banks could be capitalized at say forty percent, is this not a model worth looking at once again?

Here is a 1987 Cato Institute defense of non-bank banks. Here is further background. And you can trace Adam’s posts on the idea here.

Opinions on the new gdp growth data

You’ll find them here, I’m with Dan Greenhaus:

That is slower that virtually every recovery in the last near fifty years but is not that far behind the last recovery.

Note that the level of real gdp has finally passed the previous peak from the fourth quarter of 2007, though in per capita terms it has not.

Why the current revenue model of higher education is in trouble

The picture for females is also not pleasant, all from the excellent Michael Mandel. Those are simple facts, denied by some.

Non-college grads also have seen declining wages, and so one can look at the “finish college vs. finish high school only” margin and conclude that the return to higher education is robust. Another approach is to look at the “finish college and get on a real career track” vs. “finish college and hang out” margin and conclude the sector is in trouble, which indeed is the case. Don’t get stuck looking at the old margins only, the new and powerful margin, I am sorry to say, is relative to unemployment or extreme underemployment. The status and avoid-shame returns are high enough to keep a lot of people going to college, at current prices, but the falling real wages for graduates aren’t going to sustain an enormous amount of extra sectoral growth, including on the price side. Nor do I expect the preceding orgy of student debt to repeated, at that level, anytime soon.

Is Iceland really doing so well?

I agree with Megan McArdle’s general point that the winners and losers from this financial crisis have not yet been sorted out. Here is Jon Danielsson, with some negative notes on Iceland’s economic performance:

Based on the current state of the Icelandic economy, the Fund’s claim of success [for Iceland] does not stand up to scrutiny.

- Public finances are not on a sustainable path,

- Exchange rates are not fully stable even with capital controls,

- Investment has collapsed, and

- The financial sector is dysfunctional.

At the same time, the Fund forced Iceland to impose a high interest-rate policy at the time when every other developed economy was doing the opposite…

GDP has declined by about 11% since the crisis of October 2008, but modest and volatile growth has returned, sustained primarily by an increase in private consumption catching up after two years of austerity. Worryingly, export growth is low, even with a sharp fall in the exchange rate, while investment is at a record low.

Business investment rates in Iceland equalled the EU average from 1995 to 2008, according to Eurostat.

- Over the past two years the investment rate in Iceland collapsed to 10% whilst the EU only suffered a small decline to 17%.

…Initially, the capital controls were touted as a temporary measure to prevent a sharp depreciation of the currency, but by now the domestic economy has adapted to their presence, and become increasingly inward looking. The signs point to the controls remaining.

…Unfortunately, the government has also been using the capital controls as means to implement industrial policy, politically selecting those allowed to use cheap offshore kronas to buy Icelandic assets. Such direct political selection of investors can only breed corruption, mistrust, and inefficiency.