Category: Economics

Recent economic development stars

Development stars of the Era of Globalization: pic.twitter.com/8VOKPpFTSA

— Noah Smith 🐇🇺🇸🇺🇦 (@Noahpinion) January 27, 2023

And of course all be getting Noah Smith’s Substack…

Staking “Income” Should Not be Taxed

Staking income from tokens should not be taxed. Since staking income is generated by inflation it doesn’t create new wealth but simply lowers the total value of the token. Thus staking income is really just a transfer from non-stakers to stakers.

Abraham Sutherland covers the law and the economics in Phantom Income and the Taxation of New Cryptocurrency Tokens, a piece for Tax Notes, Here’s one bit on the economics:

Consider a simple proof-of-stake cryptocurrency in which 10 people each hold 1,000 tokens. To make sure that holders are encouraged to stake — that is, to validate transactions and add blocks to the blockchain — block rewards increase the total number of tokens by 10 percent over the course of a year. So a year later, 11,000 tokens will be on the network.

If every holder stakes and acquires a proportionate share of these new tokens, each will end the year with 1,100 tokens. Everyone has 10 percent more tokens, but no one is better off from staking. Taxing each staker’s 100 new tokens as income would be wrong. It would be like taxing the new shares created in an 11-for-10 stock split.

There is indeed an economic incentive to help keep such a cryptocurrency network secure by staking, but it’s not the one suggested by bitcoin miners making a profit even after spending on specialized computer hardware and the electricity needed to run it. The incentive in this proof-of-stake example is to avoid losing out. If everyone stakes, no one gains.

This is a profoundly elegant, equitable, and cost-effective solution to a deep coordination problem. It allows everyone who holds tokens to participate in adding new blocks and keeping the network securely decentralized. It eliminates major costs — specialized computer hardware, electricity — as requirements for fairly distributing the right to create those new blocks. In its Platonic form — in which everyone participates — no one gains at all from the new tokens, which means no one loses, either.

But this model simply won’t work if it’s taxed incorrectly. If the government sees phantom income and taxes it, the value of the network will be siphoned off to the treasury even if no one has actual gains from staking.

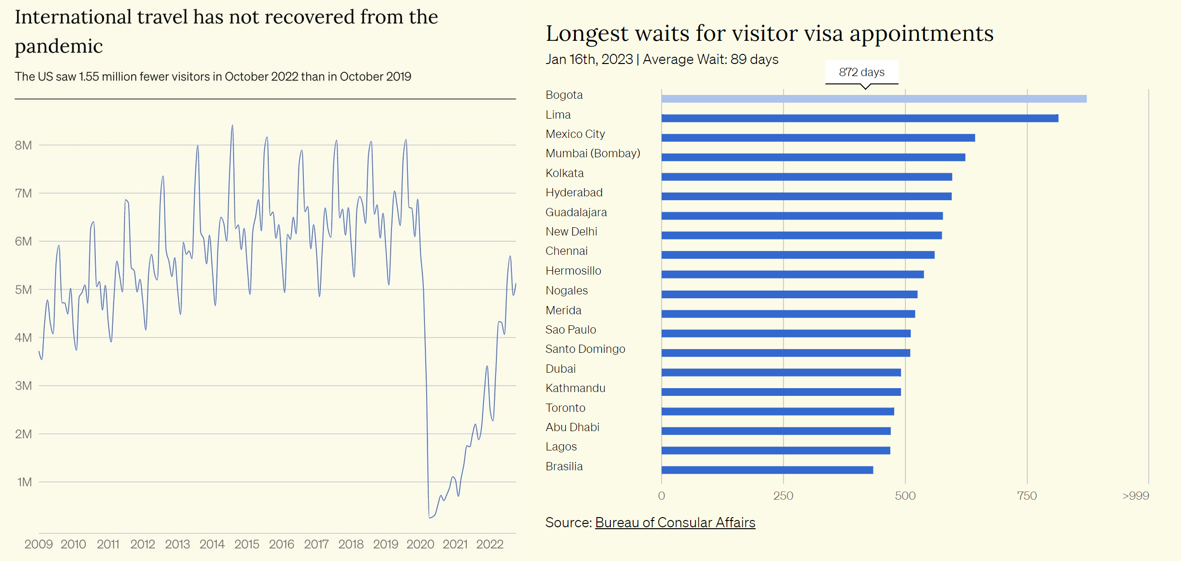

Fewer Visitors to the US

International travel to the United States is well below pre-pandemic levels, hurting our tourism industries, and embarrassingly long times to get a visitor visa are probably part of the problem.

International travel to the United States is well below pre-pandemic levels, hurting our tourism industries, and embarrassingly long times to get a visitor visa are probably part of the problem.

Hat tip: Alec Stapp.

Alex Epstein’s *Fossil Future*

Bryan Caplan asked me to read this book, and Alex Epstein was kind enough to provide me with a copy of it. The subtitle is Why Global Human Flourishing Requires More Oil, Coal, and Natural Gas — Not Less.

My overall view is this: it is a good rebuttal to “the unrealistic ones,” who don’t see the benefits of fossil fuels. But it does not rebut a properly steelmanned case for a transition away from fossil fuels.

I view the steelmanned case as this: we cannot simply keep on producing increasing amounts of carbon emissions for centuries on end. We thus need some trajectory where — at a pace we can debate — carbon emissions end up declining. I’ve stressed on MR many times that climate change is not in fact an existential risk, but it could be a civilization-destroying risk if we just keep on boosting carbon emissions without end. I don’t know a serious scientist who takes issue with that claim.

In a number of places, such as pp.251-252, and most significantly chapter nine, Epstein denies the likelihood of climate apocalypse, but I just don’t see that he has much of a counter to the standard, more quantitative accounts. He should try to publish his more optimistic take using actual models, and see if it can survive peer review. Why should I be convinced in the meantime? I found chapter nine the weakest part of the book. Maybe he feels he wouldn’t get a fair knock by trying to publish his alternative take through “the standard process,” but as it stands his casual take doesn’t come close to overturning what I consider to be the most rational, consensus-based Bayesian estimate of the consequences of making no transition to green energy.

I am also impressed by how many different kinds of scientists accept these conclusions, and see these conclusions mirrored in their own research. If you ask say the oceanographers, they will give you a broadly consistent account as the climate scientists proper.

Nor is there, for my taste, enough discussion of how much climate risk we should be willing to take on. It is not just about “beliefs most likely to be true.” Note that the less you believe in climate models, the more you should be worried about tail risk. In these matters, do not assume that uncertainty is the friend of inaction.

So I really do think we need to deviate from the world’s recent course with respect to fossil fuels. Now, we can believe that claim and simultaneously believe it would be better if Burkina Faso were much richer, even though that likely would be accompanied by more fossil fuel use, at least for a considerable period of time.

Epstein focuses on the Burkina Faso sort of issue, and buries the long-term risk of no real adjustment. But we do have to adjust. Why could he not have had the subtitle: “Why Global Human Flourishing Requires More Oil, Coal, and Natural Gas for a while, and Then Less”? Then I would be happier. In economic language, you could say he is not considering enough of the margins.

I think he is also too pessimistic about the long-run and even medium-run futures of alternative energy sources. More generally, I don’t think a few book chapters — by anyone with any point of view — can really settle that. I find the market data on green investments more convincing than his more abstract arguments (yes, I know a lot of those investments are driven by subsidies and regulation, but there is genuine change afoot).

I worry about his list of experts presented on pp.29-30. Mostly they are very weak, and this returns to my point about steelmanning.

In his inscription to the book Epstein calls me a contrarian — but he is the contrarian here! And I believe his position is likely to retain that designation. There is a lot in the book which is good, and true, nonetheless I fear the final message of the work will lower rather than raise social welfare.

For another point of view, here are various Bryan Caplan posts defending Epstein’s arguments. In any case, I thank Alex for the book.

Did the Covid housing boom induce the Great Resignation?

Following the Covid-19 pandemic, U.S. labor force participation declined significantly in 2020, slowly recovering in 2021 and 2022 — this has been referred to as the Great Resignation. The decline has been concentrated among older Americans. By 2022, the labor force participation of workers in their prime returned to its 2019 level, while older workers’ participation has continued to fall, responsible for almost the entire decline in the overall labor force participation rate. At the same time, the U.S. experienced large booms in both the equity and housing markets. We show that the Great Resignation among older workers can be fully explained by increases in housing wealth. MSAs with stronger house price growth tend to have lower participation rates, but only for home owners around retirement age — a 65 year old home owner’s unconditional participation rate of 44.8% falls to 43.9% if he experiences a 10% excess house price growth. A counterfactual shows that if housing returns in 2021 would have been equal to 2019 returns, there would have been no decline in the labor force participation of older Americans.

That is from a new paper by Jack Y. Favilukis and Gen Li, via Scott Lincicome.

Okie-dokie, crypto-based fiscal policy edition

This study examines the impact of government financial assistance during the COVID-19 pandemic on the demand for crypto assets and the effect of crypto interest on the stated goals of stimulus programs. Government lending to small businesses (PPP) significantly increased households’ interest in crypto assets. Using a Bartik instrumental variable for PPP distribution, we find that a one standard deviation increase in PPP disbursement is associated with an increase in crypto-related Google searches. A 100% percent increase in PPP disbursements is also accompanied by a 2% increased number of new wallets, 10% higher trading volume, 23% higher miners’ revenue, and a shift from large to small addresses, suggesting that government assistance increases the demand for cryptos, particularly among new, retail investors. We further find that about 5-14% of PPP loans are diverted to crypto assets, rendering PPP less effective in maintaining employment. Our results are stronger for MSAs with a less educated population, supporting a house money explanation.

That is from a new paper by Jeremy Bertomeu, Xiumin Martin, and Sheryl Zhang. Via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

The voice of monetary policy

As I mentioned recently, a new version of the surveillance society is on its way:

We develop a deep learning model to detect emotions embedded in press conferences after the Federal Open Market Committee meetings and examine the influence of the detected emotions on financial markets. We find that, after controlling for the Federal Reserve’s actions and the sentiment in policy texts, a positive tone in the voices of Federal Reserve chairs leads to significant increases in share prices. Other financial variables also respond to vocal cues from the chairs. Hence, how policy messages are communicated can move the financial market. Our results provide implications for improving the effectiveness of central bank communications.

That is by Yuriy Gorodnichenko, Tho Pham, and Oleksandr Talavera, and it is a new piece in the American Economic Review. This game of course has just started, and countermeasures will at some point arrive. You may recall I discussed exactly these possibilities in my 2013 book Average is Over.

Indoor Air Quality and Learning

More on the surprisingly large effects of air pollution on cognition from Palacios, Eichholtz, Kok and Duran:

Governments devote a large share of public budgets to construct, repair, and modernize school facilities. However, evidence on whether investments in the physical state of schools translate into better student outcomes is scant. In this study, we report the results of a large field study on the implications of poor air quality inside classrooms − a key performance measure of school mechanical ventilation systems. We continuously monitor the air quality (i.e., CO2), together with a rich set of indoor environmental parameters in 216 classrooms in the Netherlands. We link indoor air quality conditions to the outcomes on semi-annual nationally standardized tests of 5,500 children, during a period of five school terms (from 2018 to 2020). Using a fixed-effects strategy, relying on within-pupil changes in air quality conditions and test results, we document that exposure to poor indoor air quality during the school term preceding a test is associated with significantly lower test results: a one standard deviation increase in the school-term average daily peak of CO2 leads to a 0.11 standard deviation decrease in subsequent test scores. The estimates based on plausibly exogenous variation driven by mechanical ventilation system breakdown events confirm the robustness of the results. Our results add to the ongoing debate on the determinants of student human capital accumulation, highlighting the role of school infrastructure in shaping learning outcomes.

Note that the authors have data on the same students in high and low pollution episodes, allowing them to control for a wide variety of other factors.

Here are previous MR posts on air pollution including Why the New Pollution Literature is Credible and our MRU video on the Hidden Costs of Air Pollution. Note that you can take lower bounds of these effects and still think we are not paying enough attention to the costs of air pollution.

Are macroeconomic models true only “locally”?

That is the theme of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one excerpt:

It is possible, contrary to the predictions of most economists, that the US will get through this disinflationary period and make the proverbial “soft landing.” This should prompt a more general reconsideration of macroeconomic forecasts.

The lesson is that they have a disturbing tendency to go wrong. It is striking that Larry Summers was right two years ago to warn about pending inflationary pressures in the US economy, when most of his colleagues were wrong. Yet Summers may yet prove to be wrong about his current warning about the looming threat of a recession. The point is that both his inflation and recession predictions stem from the same underlying aggregate demand model.

You will note that yesterday’s gdp report came in at 2.9%, hardly a poor performance. And more:

It is understandable when a model is wrong because of some big and unexpected shock, such as the war in Ukraine. But that is not the case here. The US might sidestep a recession for mysterious reasons specific to the aggregate demand model. The Federal Reserve’s monetary policy has indeed been tighter, and disinflations usually bring high economic costs.

It gets more curious yet. Maybe Summers will turn out to be right about a recession. When recessions arrive, it is often quite suddenly. Consulting every possible macroeconomic theory may be of no help.

Or consider the 1990s. President Bill Clinton believed that federal deficits were too high and were crowding out private investment. The Treasury Department worked with a Republican Congress on a package of fiscal consolidation. Real interest rates fell, and the economy boomed — but that is only the observed correlation. The true causal story remains murky.

Two of the economists behind the Clinton package, Summers and Bradford DeLong, later argued against fiscal consolidation, even during the years of full employment under President Donald Trump [and much higher national debt]. The new worry instead was secular stagnation based on insufficient demand, even though the latter years of the Trump presidency saw debt and deficits well beyond Clinton-era levels.

The point here is not to criticize Summers and DeLong as inconsistent. Rather, it is to note they might have been right both times.

And what about that idea of secular stagnation — the notion that the world is headed for a period of little to no economic growth? The theory was based in part on the premise that global savings were high relative to investment opportunities. Have all those savings gone away? In most places, measured savings rose during the pandemic. Yet the problem of insufficient demand has vanished, and so secular stagnation theories no longer seem to apply.

To be clear, the theory of secular stagnation might have been true pre-pandemic. And it may yet return as a valid concern if inflation and interest rates return to pre-pandemic levels. The simple answer is that no one knows.

Note that Olivier Blanchard just wrote a piece “Secular Stagnation is Not Over,” well-argued as usual. Summers, however, has opined: “we’ll not return to the era of secular stagnation.” I was not present, but I can assume this too was well-argued as usual!

The Great (British) Stagnation

David Wallace-Wells in the NYTimes:

In December, as many as 500 patients per week were dying in Britain because of E.R. waits, according to the Royal College of Emergency Medicine, a figure rivaling (and perhaps surpassing) the death toll from Covid-19. On average, English ambulances were taking an hour and a half to respond to stroke and heart-attack calls, compared with a target time of 18 minutes; nationwide, 10 times as many patients spent more than four hours waiting in emergency rooms as did in 2011. The waiting list for scheduled treatments recently passed seven million — more than 10 percent of the country — prompting nurses to strike. The National Health Service has been in crisis for years, but over the holidays, as wait times spiked, the crisis moved to the very center of a narrative of national decline.

It’s not just the NHS

By the end of next year, the average British family will be less well off than the average Slovenian one, according to a recent analysis by John Burn-Murdoch at The Financial Times; by the end of this decade, the average British family will have a lower standard of living than the average Polish one.

Wallace-Wells puts the blame on “austerity”. I see austerity as more obviously a consequence than a cause of stagnation. Government spending in Poland and Slovenia is modestly less than in the UK and the central government in Poland and Slovenia spend far less than the UK does on health. The question is not why the UK spends less–it doesn’t–the question is why it spends so much and gets so little.

Alas Paul David has passed away, RIP

I report, with great sadness, the passing of Paul David. A fabulous scholar of economic history and the economics of technology, he lit up Stanford for six decades. https://t.co/90ylP7yvK0

— Tim Bresnahan (@timobres) January 25, 2023

National Average is Over

This paper considers the implications for developing countries of a new wave of technological change that substitutes pervasively for labor. It makes simple and plausible assumptions: the AI revolution can be modeled as an increase in productivity of a distinct type of capital that substitutes closely with labor; and the only fundamental difference between the advanced and developing country is the level of TFP. This set-up is minimalist, but the resulting conclusions are powerful: improvements in the productivity of “robots” drive divergence, as advanced countries differentially benefit from their initially higher robot intensity, driven by their endogenously higher wages and stock of complementary traditional capital. In addition, capital—if internationally mobile—is pulled “uphill”, resulting in a transitional GDP decline in the developing country. In an extended model where robots substitute only for unskilled labor, the terms of trade, and hence GDP, may decline permanently for the country relatively well-endowed in unskilled labor.

That is from a 2020 IMF working paper by Cristian Alonso, Andrew Berg, Siddharth Kothari, Chris Papageorgiou, and Sidra Rehman. Via Eric Yu.

Gender and tone in recorded economics presentations

You’re going to see a lot more research papers like this one:

This paper develops a replicable and scalable method for analyzing tone in economics seminars to study the relationship between speaker gender, age, and tone in both static and dynamic settings. We train a deep convolutional neural network on public audio data from the computer science literature to impute labels for gender, age, and multiple tones, like happy, neutral, angry, and fearful. We apply our trained algorithm to a topically representative sample of presentations from the 2022 NBER Summer Institute. Overall, our results highlight systematic differences in presentation dynamics by gender, field, and format. We find that female economists are more likely to speak in a positive tone and are less likely to be spoken to in a positive tone, even by other women. We find that male economists are significantly more likely to sound angry or stern compared to female economists. Despite finding that female and male presenters receive a similar number of interruptions and questions, we find slightly longer interruptions for female presenters. Our trained algorithm can be applied to other economics presentation recordings for continued analysis of seminar dynamics.

Some people might just stop going to recorded conferences, of course. That paper is by Amy Handlan and Haoyu Sheng, via the excellent Kevin Lewis.

Ethnic Remoteness Reduces the Peace Dividend from Trade Access

This paper shows that ethnically remote locations do not reap the full peace dividend from increased market access. Exploiting the staggered implementation of the US-initiated Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) and using high-resolution data on ethnic composition and violent conflict for sub-Saharan Africa, our analysis finds that in the wake of improved trade access conflict declines less in locations that are ethnically remote from the rest of the country. We hypothesize that ethnic remoteness acts as a barrier that hampers participation in the global economy. Consistent with this hypothesis, satellite-based luminosity data show that the income gains from improved trade access are smaller in ethnically remote locations, and survey data indicate that ethnically more distant individuals do not benefit from the same positive income shocks when exposed to increased market access. These results underscore the importance of ethnic barriers when analyzing which locations and groups might be left behind by globalization.

That is from a new NBER working paper by Klaus Desmet and Joseph F. Gomes.

Tyrone cheers up Tim Harford

If you needed someone to cheer you up, would you not want my evil twin brother Tyrone? Well, Tim Harford is a privileged fellow. Tyrone read Tim’s recent FT column “Is life in the UK really as bad as the numbers suggest? Yes, it is“, and thought Tim could use a real bucking up. Tyrone is such a cheery fellow himself, and I so thought I would let him jolly along Tim. Here is Tyrone’s proposed letter to the FT:

Britain, Britain, Britain — how tears come to my eye each time I swim the Atlantic and stride on shore. How many times have I returned and with such joy?

The high land rents in Britain are the first and foremost a sign life is really good there. You get what you pay for! And in Britain you pay a lot. You must get a lot too. For sure, the value of living here can be no lower than the entry fee. Even much of northern England is not so cheap anymore, and calling it “tea” isn’t going to change that fact.

I hear you all screaming “NIMBY!” while eating your bangers. Well, NIMBY is one reason why Britain — or some parts of it — are expensive. But NIMBY doesn’t detract from the quality signal embedded in those high prices.

Let’s say you had a luxury hotel that mismanaged its staff, and so it only opened up three rooms when it should have opened up 300 rooms. Furthermore, those three rooms are rented out for $3000 a night. You wouldn’t say the guests paying $3000 a night are miserable in the hotel. In fact you would conclude they really enjoyed the hotel, to the tune of at least $3000 a night. They could be enjoying it more at lower prices and higher capacity, but that is like saying the Beatles should have put out more albums. Both claims are true, but you wouldn’t conclude Britain had a miserable musical life.

If nothing else, the hotel analogy shows Britain has the potential to get oh so much better yet.

GPT tells me that before Brexit, 1.8% of the British population lived in other EU countries, with Spain being a clear first destination. Was that outflow so high? The sign of a ruined society? Or a mark of complacency with a pretty good thing? A lot of that was (or still is) retirees of course, yet another sign of how splendid British life can be. What could be better than earning enough in Leeds to spend your declining years in Tavira, yet close enough to fly home and see the grandkids on Boxing Day?

It is not so hard for many British people to migrate to Australia, New Zealand, Canada, or sometimes even the United States. Northern Ireland beckons too (and the homes there are pretty cheap). Those acts of migration don’t require a new language, and you might keep the royal family on your money and also on your bestseller lists, wait no they are not the royal family any more.

Chat tells me that in 2019 the net migration from the UK to Australia was about 16,000, hardly a major rebellion against economic servitude. In that same year, 26,800 Brits decided to leave the barbie and return home — clearly they missed something. Brit migrants to Australia, unlike those to Provence, are not usually the wealthy.

Tyrone has not only met Tim, but he has observed Tim living and working and succeeding in the United States. Since Tim left America, presumably he prefers Britain and the superior curries, country homes, and memories of empire. Not to mention the bookshops. Amenities! Tim is hardly the only one moving into southern England. The UK population more broadly just keeps on rising. We would gladly have Tim back, but it seems he won’t have us, stars and stripes for never.

Maybe you think some of the high rents in Britain are due to foreigners buying up property. That is true in some parts of London, but for the country as a whole? Besides, if London and Oxford give some foreigners the risk protection benefits of their real estate, is that not the cosmopolitan policy my Effective Altruist friends have been urging on me? It would be easy enough to tax them more for those benefits, any time the Brits need to.

Southern England seems geared to help the world, what with its vaccines, DeepMind, and the data on dexamethasone. How many regions are grander than that? No wonder people want to pay so much to live there. Like yours truly — Tyrone, not to mention Tim — they most of all want to help other humans.

Besides, the UK has a higher birth rate than Switzerland, Norway, or Luxembourg — so where do the real riches lie? Especially over time.

Put aside some minor problems with the health care system — my friend the very healthy Robin Hanson says it doesn’t matter much. The evidence keeps mounting that the non-pecuniary benefits of being British hardly could be higher. And they don’t even tax you on them. Strawberry Fields Forever.

TC again: Is this the most serious Tyrone has been? Is he turning over a new leaf? Have all those weekends in the Lake District rubbed off on him? But alas, he does not go to the Lake District, he prefers the darker corners of northern New Jersey. As Herodotus noted, all men consider their own ways to be best, Tyrone not excepted. And if Tyrone does not live in Britain, how can it possibly be best?

Q.E.D.

Tim Harford, I weep with you, put Tyrone out of your mind. The fish and chips is better in New Zealand anyway.