Category: Economics

*The Guest Lecture*

The author is Martin Riker, and this is a story about a jobless economics professor about to give a lecture. She is nervous, and her thoughts rapidly turn to Keynes, including his “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren” essay. She ponders the problems of the world, her husband and daughter, and Keynes, Keynes, Keynes, chatting with him throughout. On pp.54-55 Deirdre McCloskey surfaces and plays a role in the story, which shifts to the scene of a trial.

I don’t want to spoil anything, but suffice to say there are some non-literal meanings of what is happening in these pages. Overall, this is one of the more significant modern examples of a very direct overlap of economics and fiction.

You can buy it here. Here are various reviews.

Tap the Yellowstone Super-volcano!

I applaud this kind of big think!

The USA is confronted with three epic-size problems: (1) the need for production of energy on a scale that meets the current and future needs of the nation, (2) the need to confront the climate crisis head-on by only producing renewable, green energy, that is 100% emission-free, and (3) the need to forever forestall the eruption of the Yellowstone Supervolcano. This paper offers both a provable practical, novel solution, and a thought experiment, to simultaneously solve all of the above stated problems. Through a new copper-based engineering approach on an unprecedented scale, this paper proposes a safe means to draw up the mighty energy reserve of the Yellowstone Supervolcano from within the Earth, to superheat steam for spinning turbines at sufficient speed and on a sufficient scale, in order to power the entire USA. The proposed, single, multi-redundant facility utilizes the star topology in a grid array pattern to accomplish this. Over time, bleed-off of sufficient energy could potentially forestall this Supervolcano from ever erupting again. With obvious importance to our planet and the research community alike, COMSOL simulation demonstrates and proves the solution proposed herein, to bring vast amounts of green, emission-free energy to the planet’s surface for utilization. Well over 11 Quadrillion Watt hours of electrical energy generated over the course of one full year, to meet the current and future needs of the USA is shown to be practical. Going beyond other current and past research efforts, this methodology offers tremendous benefits, potentially on a planetary scale.

From Yellowstone Caldera Volcanic Power Generation Facility: A new engineering approach for harvesting emission-free green volcanic energy on a national scale by Arciuolo and Faezipour.

Hat tip: nvo.

A new and possibly important paper

The title is the somewhat awkward: “A Macroscope of English Print Culture, 1530-1700, Applied to the Coevolution of Ideas on Religion, Science, and Institutions.” The abstract is informative:

We combine unsupervised machine-learning and econometric methods to examine cultural change in 16th- and 17th-century England. A machine-learning digest synthesizes the content of 57,863 texts comprising 83 million words into 110 topics. The topics include the expected, such as Natural Philosophy, and the unexpected, such as Baconian Theology. Using the data generated via machine-learning we then study facets of England’s cultural history. Timelines suggest that religious and political discourse gradually became more scholarly over time and economic topics more prominent. The epistemology associated with Bacon was present in theological debates already in the 16th century. Estimating a VAR, we explore the coevolution of ideas on religion, science, and institutions. Innovations in religious ideas induced strong responses in the other two domains. Revolutions did not spur debates on institutions nor did the founding of the Royal Society markedly elevate attention to science.

By Peter Grazjl and Peter Murrell, here is the paper itself. Via the excellent and ever-aware Kevin Lewis.

How to tip more effectively

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here is one part of the argument:

Consider a scenario in which the initial effects of tipping are self-reversing — that is, wages will fall to offset the value of tips. If the official wage is $10 an hour and tips are on average $10 an hour, that adds up to $20 an hour. If tips from everybody — not just you, but everybody — go up by another $3 an hour, the new net wage is $23 an hour.

At that higher wage, more people will apply for the job. The increased supply of labor will allow the boss to pay less than $10 an hour; it might suffice to pay only $7. Under the new regime, with tips at $13 an hour and the formal wage at $7 an hour, $3 per hour has essentially been transferred from customers to restaurant owners. The workers don’t end up with any extra money, but the owners have snookered the customers into paying a higher share of the wage bill.

In this case, you would do better by sneaking an individual worker some money on the side. That way, at least one person would get some extra cash, while you would avoid being part of a system that results in less burden on the employer.

Note that during a labor shortage, as we currently are experiencing in many sectors, part of the benefit of tips goes to customers. The higher net wage pulls more labor in the door and improves service quality. And here are the conclusions of the piece:

- If it is only you who is tipping more, and not all customers, the gains probably go to the worker.

- For that reason, if you are going to tip more, give cash to an actual human rather than in response to a touch-screen prompt.

- If you want to give a collective tip, under normal conditions you won’t much help workers.

- Under abnormal conditions, which currently prevail, even a collective tip is more likely to reach workers, as well as attract more labor to the workforce and help your fellow customers.

- In the longer run, however, a collective tipping system will serve to transfer some of the wage burden from employers to customers.

Don’t forget general equilibrium incidence!

My Conversation with Glenn Loury

Moving throughout, here is the audio, video, and transcript. Here is part of the summary:

Economist and public intellectual Glenn Loury joined Tyler to discuss the soundtrack of Glenn’s life, Glenn’s early career in theoretical economics, his favorite Thomas Schelling story, the best place to raise a family in the US, the seeming worsening mental health issues among undergraduates, what he learned about himself while writing his memoir, what his right-wing fans most misunderstand about race, the key difference he has with John McWhorter, his evolving relationship with Christianity, the lasting influence of his late wife, his favorite novels and movies, how well he thinks he will face death, and more.

Here is one excerpt:

COWEN: What’s your favorite Thomas Schelling story?

LOURY: [laughs] This is a story about me as much as it is about Tom Schelling. The year is 1984. I’ve been at Harvard for two years. I’m appointed a professor of economics and of Afro-American studies, and I’m having a crisis of confidence, thinking I’m never going to write another paper worth reading again.

Tom is a friend. He helped to recruit me because he was on the committee that Henry Rosovsky, the famous and powerful dean of the college of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Harvard, who hired me — the committee that Rosovsky put together to try to find someone who could fill the position that I was hired into: professor of economics and of Afro-American Studies. They said Afro-American in those years.

Tom was my connection. He’s the guy who called me up when I was sitting at Michigan in Ann Arbor in early ’82, and said, “Do you think you might be interested in a job out here?” He had helped to recruit me.

So, I had this crisis of confidence. “Am I ever going to write another paper? I’m never going to write another paper.” I’m saying this to Tom, and he’s sitting, sober, listening, nodding, and suddenly starts laughing, and he can’t stop, and the laughing becomes uncontrollable. I am completely flummoxed by this. What the hell is he laughing at? What’s so funny? I just told him something I wouldn’t even tell my wife, which is, I was afraid I was a failure, that it was an imposter syndrome situation, that I could never measure up.

Everybody in the faculty meeting at Harvard’s economics department in 1982 was famous. Everybody. I was six years out of graduate school, and I didn’t know if I could fit in. He’s laughing, and I couldn’t get it. After a while, he regains his composure, and he says, “You think you’re the only one? This place is full of neurotics hiding behind their secretaries and their 10-foot oak doors, fearing the dreaded question, ‘What have you done for me lately?’ Why don’t you just put your head down and do your work? Believe me, everything will be okay.” That was Tom Schelling.

COWEN: He was great. I still miss him.

And the final question:

COWEN: Very last question. Do you think you will do a good job facing death?

Interesting and revealing throughout.

*The Time Travelling Economist*

The author is Charlie Robertson, and the subtitle is Why Education, Electricity and Fertility are Key to Escaping Poverty.

How come no one told me about this book before? Published in 2022 (in Switzerland), it is one of the best popular economics books of the last decade, and one of the best books on economic development period. People should talk about it more! And to be sure, that description “popular” is misleading. Like other good books in this genre, it is deeper and better than merely being “popular,” even if it does not itself present original research of the kind you might find in a journal.

Anyway, the core argument is reflected well in the subtitle, and here is one excerpt:

Electricity is an integral part of the investment story that all countries require to escape poverty and eventually progress to become rich. The commonly cited metric is that investment needs to be 25% of GDP and those that beat this, grow fast. In this chapter, we use electricity as a proxy for that investment target.

There are good insights throughout, for instance:

Many have high hopes for solar power in Nigeria, but one problem is keeping them secure. Solar panels might be at risk of theft to replace the expensive diesel generator that so many households have to rely on.

The author has considerable real world experience through his Global Chief Economist position at Renaissance Capital. Here is another good bit:

When fertility rates fall, country’s banking systems will get larger.

And:

A debt crisis is probably unavoidable in a bid to create jobs.

The author is bullish on Pakistan, North Africa, Ghana, Kenya and Rwanda. For better or worse, some of those picks reflect the fact that “politics” does not feature directly in his key jumping-off points for growth. We will see.

There are various objections you can levy at this book, ranging from “lack of a fully specified model” (who has that anyway?) to “those factors are themselves endogenous to [fill in the blank].” I’ll just say that I have seen many a worse economic development book, and this one is not ideologically charged either.

You can order it here.

Yglesias on Operation Warp Speed and the Republicans

Here’s Yglesias on Operation Warp Speed and the Republicans:

The debate over Operation Warp Speed wasn’t just a one-off policy dispute. Long before the pandemic, there was a conservative critique that the Food and Drug Administration is too slow and too risk-averse when it comes to authorizing new medications. Alex Tabarrok, a George Mason University economist, wrote about the “invisible graveyard” that could have been avoided if the FDA took expected value more seriously and considered the cost of delay in its authorization decisions.

The pandemic experience validated this criticism, which came to be embraced by some on the left as well — and it was about more than just vaccines. When it came to home Covid tests, Ezra Klein noted in the New York Times in 2021, “the problem here is the Food and Drug Administration. They have been disastrously slow in approving these tests and have held them to a standard more appropriate to doctor’s offices than home testing.”

And yet, just as the invisible graveyard was becoming seen and the debate was being won and just as a historical public-private partnership had sped vaccines to the public and saved millions, the Republicans abandoned the high ground:

…it’s not surprising that Democrats are comfortable with the bureaucratic status quo and hesitant to ruffle feathers at federal regulatory agencies. What’s shocking is that Republicans — the traditional party of deregulation, the party that argued for years that the FDA is too slow-footed, the party that saved untold lives by accelerating vaccine development under Trump — have abandoned these positions.

At the cusp of what should have been a huge policy victory, Republicans don’t brag about their success, and they have no FDA reform legislation to offer. Instead, they’ve taken up the old mantle of hard-left skepticism of modern science and the pharmaceutical industry.

It’s been painful to see all that has been gained now being lost. Libertarian economists and conservatives argued for decades that the FDA worried more about approving a drug that later turns out to be unsafe than about failing to approve a drug that could save lives; thus producing a deadly caution. But now the FDA is being attacked for what they did right, quickly approving safe vaccines. I hope that he is wrong but I fear that Yglesias is correct that the FDA may now get even slower and more cautious.

The irony of the present moment is that there is substantial backlash to the FDA’s approval of vaccines that haven’t turned out to be dangerous at all.

That’s only going to make regulators even more cautious. Right now the entire US regulatory state is taking essentially no heat for the slow progress on the next generation of vaccines, and an enormous amount of heat for the perfectly safe vaccines that it already approved. And the ex-president who pushed them to speed up their work on those vaccines is not only no longer defending them, he’s embarrassed to have ever been associated with the project.

Like I said, it’s a comical moment of Republican infighting. But it’s a very grim one for anyone concerned with the pace of scientific progress in America.

Klein on Construction

Here’s Klein writing about construction productivity in the New York Times:

Here’s something odd: We’re getting worse at construction. Think of the technology we have today that we didn’t in the 1970s. The new generations of power tools and computer modeling and teleconferencing and advanced machinery and prefab materials and global shipping. You’d think we could build much more, much faster, for less money, than in the past. But we can’t. Or, at least, we don’t.

…A construction worker in 2020 produced less than a construction worker in 1970, at least according to the official statistics. Contrast that with the economy overall, where labor productivity rose by 290 percent between 1950 and 2020, or to the manufacturing sector, which saw a stunning ninefold increase in productivity.

In the piquantly titled “The Strange and Awful Path of Productivity in the U.S. Construction Sector,” Austan Goolsbee, the newly appointed chairman of the Chicago Federal Reserve and the former chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Barack Obama, and Chad Syverson, an economist at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, set out to uncover whether this is all just a trick of statistics, and if not, what has gone wrong.

After eliminating mismeasurement and some other possibilities following Goolsbee and Syverson, Klein harkens back to our discussion of Mancur Olson’s Rise and Decline of Nations and offers a modified Olson thesis, namely too may veto points.

…It’s relatively easy to build things that exist only in computer code. It’s harder, but manageable, to manipulate matter within the four walls of a factory. When you construct a new building or subway tunnel or highway, you have to navigate neighbors and communities and existing roads and emergency access vehicles and politicians and beloved views of the park and the possibility of earthquakes and on and on. Construction may well be the industry with the most exposure to Olson’s thesis. And since Olson’s thesis is about affluent countries generally, it fits the international data, too.

I ran this argument by Zarenski. As I finished, he told me that I couldn’t see it over the phone, but he was nodding his head up and down enthusiastically. “There are so many people who want to have some say over a project,” he said. “You have to meet so many parking spaces, per unit. It needs to be this far back from the sight lines. You have to use this much reclaimed water. You didn’t have 30 people sitting in an hearing room for the approval of a permit 40 years ago.”

This also explains why measured regulation isn’t necessarily determinative. Regulation provides the fulcrum but it’s interest groups that man the lever.

Some of this is expressed through regulation. Anyone who has tracked housing construction in high-income and low-income areas knows that power operates informally, too. There’s a reason so much recent construction in Washington, D.C., has happened in the city’s Southwest, rather than in Georgetown. When richer residents want something stopped, they know how to organize — and they often already have the organizations, to say nothing of the lobbyists and access, needed to stop it.

This, Syverson said, was closest to his view on the construction slowdown, though he didn’t know how to test it against the data. “There are a million veto points,” he said. “There are a lot of mouths at the trough that need to be fed to get anything started or done. So many people can gum up the works.”

Read the whole thing.

The final collapse of CAPM?

The key purpose of corporate finance is to provide methods to compute the value of projects. The baseline textbook recommendation is to use the Present Value (PV) formula of expected cash flows, with a discount rate based on the CAPM. In this paper, we ask what is, empirically, the best discounting method. To do this, we study listed firms, whose actual prices and expected cash flows can be observed. We compare different discounting approaches on their ability to predict actual market prices. We find that discounting based on expected returns (such as variants on the CAPM or multi-factor model), performs very poorly. Discounting with an Implied Cost of Capital (ICC), imputed from comparable firms, obtains much better results. In terms of pricing methods, significant, but small, improvements can be obtained by allowing, in a simple and actionable way, for a more flexible term structure of expected returns. We benchmark all of our results with flexible, purely statistical models of prices based on Random Forest algorithms. These models do barely better than NPV-based methods. Finally, we show that under standard assumptions about the production function, the value loss from using the CAPM can be sizable, of the order of 10%.

That is from a new NBER paper by Nicholas Hommel, Augustin Landier, and David Thesmar. Via David Thesmar.

Industrial policy is the new globalization

That is the topic of my latest Bloomberg column, here goes:

It would be a mistake, however, to think that these [industrial] policies represent a move away from globalization. In fact they are an extension of globalization — and they likely will enable yet more globalization to come. That sounds counterintuitive, so let me explain.

Start with the domestic subsidies for green energy, as embodied in 2022’s Inflation Reduction Act. Those policies favor domestic firms in industries such as electric vehicles, batteries, and solar power. You could call that nationalism or even mercantilism. Yet those subsidies rely not only on a prior history of globalization but also an expected future for globalization. To the extent the US is able to extend its domestic battery production, it is because more lithium and other raw materials can be produced overseas and exported to the US. To the extent the US succeeds with its domestic solar industry, it is by drawing upon earlier advances in Spain, Germany and China — and undoubtedly future advances to come.

Even the most successful “nationalistic” industrial policies rely on a highly globalized world. If carried out strictly on a one-nation basis, industrial policy is doomed to fail. Globalization has been so thorough, and has gone so well, that at least a little industrial policy is now thinkable for many nations.

And this:

Just as globalization can enable or support nationalist industrial policy, so the converse is true. Assume that these various industrial policies meet with some degree of success, and that China, the EU and the US all become more self-sufficient in various ways. Those same political units are more likely to then embrace and support further globalization…

Some conservatives criticize globalization while praising industrial policy. They are playing right into the hands of the Davos globalizing elite. In fact, that is the best argument for many of these ideas: Today’s industrial policy is not an alternative to globalization. It is preparing the world for the next round of it.

I don’t think the Nat Cons have fully digested this lesson yet.

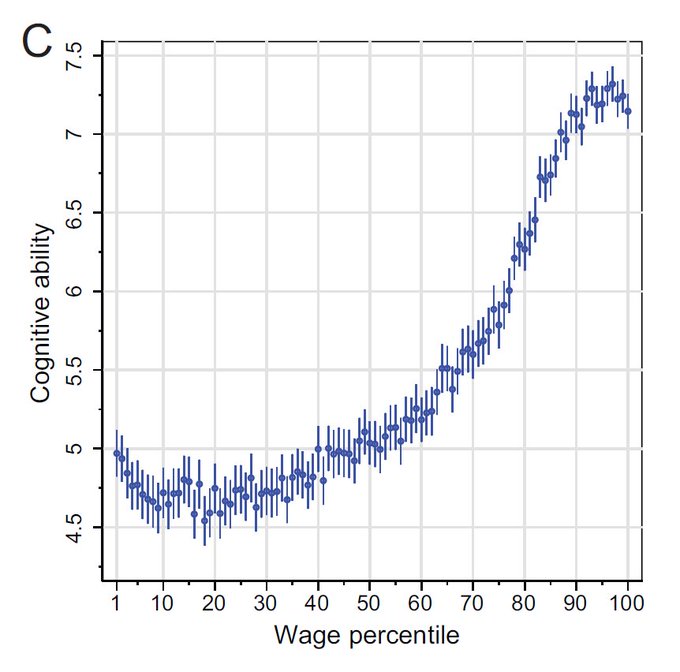

The plateauing of cognitive ability among top earners

Are the best-paying jobs with the highest prestige done by individuals of great intelligence? Past studies find job success to increase with cognitive ability, but do not examine how, conversely, ability varies with job success. Stratification theories suggest that social background and cumulative advantage dominate cognitive ability as determinants of high occupational success. This leads us to hypothesize that among the relatively successful, average ability is concave in income and prestige. We draw on Swedish register data containing measures of cognitive ability and labour-market success for 59,000 men who took a compulsory military conscription test. Strikingly, we find that the relationship between ability and wage is strong overall, yet above €60,000 per year ability plateaus at a modest level of +1 standard deviation. The top 1 per cent even score slightly worse on cognitive ability than those in the income strata right below them. We observe a similar but less pronounced plateauing of ability at high occupational prestige.

That is from a new paper by Marc Keuschnigg, Arnout van de Rijt3, and Thijs Bol.

Real Return Bonds–Not a Loony Idea

The Canadian government has said it will stop issuing real return bonds, i.e. inflation indexed bonds. Real return bonds are extremely useful to anyone who wants a steady stream of income that keeps up with inflation—retirees, for example. A real return bond would also be ideal for funding an endowment such as a university chair or scholarship program. I agree with John Cochrane and Jon Hartley writing in the G&M that ending sales of these bonds is a bad signal.

So why stop issuing real return bonds? The government may suspect that inflation will go up a lot more, and it will then have to pay more to bondholders. Non-indexed debt can be inflated away if the fiscal situation worsens. The cumulative 11-per-cent inflation since January, 2021, has inflated away 11 per cent of the debt already. Argentines have seen a lot more.

But issuing indexed debt makes sense if the government plans to be responsible. Tax payments and budget costs rise with inflation, and fall with disinflation, so the budget is stabilized if inflation-indexed bond payments do the same. And issuing indexed debt that can’t be inflated away is a good incentive not to turn around and inflate debt away.

Rasheed Griffith on the need for a Caribbean think tank

Worth another link! Here is one bit:

In my opinion, the first priority for a Caribbean think tank or program should be to advocate for the implementation of dollarization, which involves the replacement of all existing Caribbean currencies with the United States Dollar (USD) as the sole currency. This idea is based on the numerous fiscal and monetary shortcomings exhibited by Caribbean governments. The benefit of this proposal is its widespread latent approval and straightforward nature, making it easier to garner support and understanding among the Caribbean people…

The domestic money of Caribbean countries are only useful in the tiny land area of the earth where they are issued. For example, Barbados is 166 square miles and the Barbados Dollar (BBD) only has value in that small space. Why exactly should people be forced to exchange their labour for money that has such a limited use?

You might say that they can easily exchange the Barbados Dollar (BBD) for USD. But that is untrue. Barbados maintains strict capital controls because it cannot allow people to exchange too much BBD for USD as that would cause a crisis for the fixed exchange rate. This is a kafkaesque policy since virtually everything imported into and exported from Barbados is priced and invoiced in USD.

Moreover, the government abuses its position as the issuer of money. Primarily to finance its spendthrift operations by arbitrarily creating new money. This is the evident across the region. In Trinidad & Tobago, the government limited citizens to only a $250 USD allotment for international purchases on credit cards. This forced the black market rate to unprecedented levels, with everyone desperate to acquire USD. It came to a point where some services would give discounts if you pay in USD.

Basic point: Caribbean people are severely disadvantaged by being forced to use money that has no global acceptance. Caribbean governments will perpetually mismanage their domestic money to the detriment of citizens.

The manifesto covers many other issues, interesting throughout.

Where will the impact of ChatGPT fall? (from my email)

One dialogue that is missing from the current GPT conversations is about where these technologies will be primarily implemented.

There are two places GPTs can be used:

- Product-level: Implemented within products that companies buy

- Process-level: Implemented within processes of a company by an analyst – similar to how companies use data analysts today

If the future has primarily Product-level GPT, then companies like Microsoft clearly win because they have the products (like Teams) where the tech will be embedded and if you want the productivity gains from GPTs you have to go through them.

If the future has more Process-level GPT, companies like Zapier and no-code platforms win, because they will be the tools that companies use to implement their custom prompts. (although maybe a “Microsoft Teams Prompt Marketplace” wins as well)

The advantage to Process-level GPT is that companies don’t have to go through expensive change management to fit imperfect processes decreed by an external product – they can have their prompts designed to fit their specific needs. This would lead to higher productivity increases than a world with purely Product-level GPT.

To me, it comes down to the question of how much technical debt a custom prompt represents. If each prompt requires lots of maintenance and testing, then MSFT dominates. If someone who has 1 year of experience and used ChatGPT to write their papers in college can make a robust prompt, then Zapier wins.

Between the iterations of GPT3 so far (from davinci-001 to davinci-003/ChatGPT), we’ve seen the robustness of prompts increase exponentially. If this continues, it seems possible that the future has more Process-level GPT than we’ve seen so far.

Not edited by ChatGPT,

Neil [Madsen]

Is there any reheating scenario?

It is not the most likely scenario, but is nonetheless worth a ponder, as I outlined in my latest Bloomberg column:

Consider a simple scenario involving output and money, much of which takes the form of credit expansion by banks and other intermediaries. In a well-functioning economy, money and output grow at roughly the same rate.

When economies experience turnarounds, however, conditions on the ground can change rapidly. In such circumstances, the growth of the money supply might outpace the growth in output — even if the central bank does not intend such a result. The reason is that output can take a while to grow. Businesses might have to expand capacity or hire more workers, and right now there is still a labor shortage. Even when an economy is functioning well and business conditions are good, output often grows with a lag.

The money supply, however, need not suffer from a lag. Banks, for instance, can extend credit quickly if they foresee that a recovery is stronger than expected. Even if a bank is in the midst of processing a loan, it can simply lend out more than it was planning.

Thus there can be periods when, for entirely natural reasons, the money supply is rising faster than output. That situation requires only a sudden burst of good news. And indeed there has been exactly that with the recent favorable inflation reports and the surprisingly good recent GDP report. The irony is that a positive market response to low inflation and strong growth cheers up market participants and could lead to … a new dose of inflation.

Another possible pathway for these scenarios involves interest rates. During a normal disinflation, the Federal Reserve raises rates and keeps them high for a long period of time while the economy adjusts slowly — often passing through recession. But inflation has fallen more rapidly than expected, and so the market may expect the Fed to lower interest rates sooner than planned. And an expected cut in interest rates can encourage expansionary pressures just as much as an actual cut in interest rates.

It is a funny world in which slow inflation can cause faster inflation. It’s the logic of expectations that makes it possible, albeit far from certain.

Inflation isn’t going back up to where it was, but please do keep in mind that numbers can move in both directions.